James Connolly and the Reconquest of Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download a PDF of an Chéad Dáil Éireann Commemorative

Eisithe ag Teachtaí Dála agus Seanadóir Shinn Féin, Eanáir 2009 (0612) Untitled-2 1 15/01/2009 12:47:17 Teachtaireacht ó Ionadaithe Shinn Féin san Oireachtas Message from Sinn Féin Members of the Oireachtas Is onóir dúinn mar ionadaithe tofa Shinn Féin san Oireachtas Had the British government then abided by the an foilseachán seo a chur ar fáil mar chomóradh ar an gCéad democratically expressed will of the Irish people, Ireland Dáil Éireann. and Britain would have been spared many decades of strife and suffering. Instead Dáil Éireann was suppressed. War was Ar an 21ú lá Eanáir 1919 d’fhoilsigh Dáil Éireann an Faisnéis waged on the Irish people. Partition was imposed and we Neamhspleachais, an Teachtaireacht chun Saor-Náisiúin an are still living with the legacy today. Domhain agus an Clár Oibre Daonlathach. Tá na cáipéisí sin curtha ar fáil arís againn agus molaimid iad mar treoir do But we also have the rich legacy of Dáil Éireann, the phobal na hÉireann i 2009. constituent assembly of the Irish Republic. It met for the first time on 21 January 1919 in Dublin’s Mansion House. January 2009 marks the 90th anniversary of the inaugural It issued a Declaration of Independence and a Message to meeting of the First Dáil Éireann and, as Sinn Féin the Free Nations of the World. It set out social and economic representatives in the Oireachtas, we are proud to make goals based on equality in its Democratic Programme. It available this commemorative publication. formed a Government that included one of the first women Ministers in the world. -

Arts and Sciences By

THE IRISH UPRISING OF EASTER 1916 AND THE EMERGENCE , , OF EAMON DE VALERA AS THE LEADER OF THE IRISH REPUBLICAN MOVEMENT i\ THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN'S UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY BARBARA ANN LAMBERTH, B.S. DENTON, TEXAS AUGUST, 197 4 Texas Woman's University Denton, Texas ____J_u_n_e_26 .,_ 19 __7-1 __ _ We hereby recommend that the thesis prepared wider our supervision by Barbara Ann Lamberth "The Irish Uprising of Easter 1916 and entitled . �· � the Emergence of Eamon de Valera as the Leader of the Irish Republican Movement" be accepted as fulfilling this part of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. Committee: f\'ERSITY ,... .. ) \ ;) . TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE V CfLI\PTE R ., I. EAMON DE VALERA--THE STATESMAN . 1 II. DE VALERA--THE PRIVATE YEARS . 9 22 I I I. EASTER 1916--THE BLOOD SACRIFICE: THE PRELUDE IV. EASTER 1916--THE BLOOD SACRIFICE: MILITARY 56 ACTION . V. EASTER 1916--THE BLOOD SACRIFICE: FROM 92 DEFEAT TO VICTORY ... ........ 116 VI. DE VALERA--COMING TO LEADERSHIP .. 147 CONCLUSION APPENDIX 153 A. THE MANIFESTO OF THE IRISH VOLUNTEERS . 156 B. PROCLA MATION OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC .. • 158 c. MANIFESTO TO THE PEOPLE OF DUBLIN . 160 D. SPEECH OF DE VALERA .. , 163 E. THE MANIFESTO OF SINN FEIN F. THE TEXT OF THE SAME MANIFESTO AS PASSED BY THE DUBLIN CASTL� CENSOR • . .. � • .. 166 G. IRISH DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE . • .•169 , , 171 H. CONSTITUTION OF DAIL EIRANN • • 1 73 I. -

The Scotch-Irish in America. ' by Samuel, Swett Green

32 American Antiquarian Society. [April, THE SCOTCH-IRISH IN AMERICA. ' BY SAMUEL, SWETT GREEN. A TRIBUTE is due from the Puritan to the Scotch-Irishman,"-' and it is becoming in this Society, which has its headquar- ters in the heart of New England, to render that tribute. The story of the Scotsmen who swarmed across the nar- row body of water which separates Scotland from Ireland, in the seventeenth century, and who came to America in the eighteenth century, in large numbers, is of perennial inter- est. For hundreds of years before the beginning of the seventeenth centurj' the Scot had been going forth con- tinually over Europe in search of adventure and gain. A!IS a rule, says one who knows him \yell, " he turned his steps where fighting was to be had, and the pay for killing was reasonably good." ^ The English wars had made his coun- trymen poor, but they had also made them a nation of soldiers. Remember the "Scotch Archers" and the "Scotch (juardsmen " of France, and the delightful story of Quentin Durward, by Sir Walter Scott. Call to mind the " Scots Brigade," which dealt such hard blows in the contest in Holland with the splendid Spanish infantry which Parma and Spinola led, and recall the pikemen of the great Gustavus. The Scots were in the vanguard of many 'For iickiiowledgments regarding the sources of information contained in this paper, not made in footnotes, read the Bibliographical note at its end. ¡' 2 The Seotch-líiáh, as I understand the meaning of the lerm, are Scotchmen who emigrated to Ireland and such descendants of these emigrants as had not through intermarriage with the Irish proper, or others, lost their Scotch char- acteristics. -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

Father Ted 5 Entertaining Father Stone 6 the Passion of Saint Tibulus 7 Competition Time 8 and God Created Woman 9 Grant Unto Him Eternal Rest 10 SEASON 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION PAGE Introduction 3 SEASON 1 Good Luck, Father Ted 5 Entertaining Father Stone 6 The Passion of Saint Tibulus 7 Competition Time 8 And God Created Woman 9 Grant Unto Him Eternal Rest 10 SEASON 2 Hell 13 Think Fast, Father Ted 14 Tentacles of Doom 15 Old Grey Whistle Theft 16 A Song for Europe 17 The Plague 18 Rock A Hella Ted 19 Alcohol and Rollerblading 20 New Jack City 21 Flight into Terror 22 SEASON 3 Are You Right There, Father Ted 25 Chirpy Burpy Cheap Sheep 26 Speed 3 27 The Mainland 28 Escape from Victory 29 Kicking Bishop Brennan Up the Arse 30 Night of the Nearly Dead 31 Going to America 32 TABLE OF CONTENTS SPECIAL EPISODES PAGE A Christmassy Ted 35 ULTIMATE EPISODE RANK 36 - 39 ABOUT THE CRITIC 40 3 INTRODUCTION Father Ted is the pinnacle of Irish TV; a much-loved sitcom that has become a cult classic on the Emerald Isle and across the globe. Following the lives of three priests and their housekeeper on the fictional landmass of Craggy Island, the series, which first aired in 1995, became an instant sensation. Although Father Ted only ran for three seasons and had wrapped by 1998, its cult status reigns to this very day. The show is critically renowned for its writing by Graham Linehan and Arthur Mathews, which details the crazy lives of the parochial house inhabitants: Father Ted Crilly (Dermot Morgan), Father Dougal McGuire (Ardal O'Hanlon), Father Jack Hackett (Frank Kelly), and Mrs Doyle (Pauline McLynn). -

Revolutionary Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War: A

Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Darlington, RR http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2012.731834 Title Re-evaluating syndicalist opposition to the First World War Authors Darlington, RR Type Article URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/19226/ Published Date 2012 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. Re-evaluating Syndicalist Opposition to the First World War Abstract It has been argued that support for the First World War by the important French syndicalist organisation, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) has tended to obscure the fact that other national syndicalist organisations remained faithful to their professed workers’ internationalism: on this basis syndicalists beyond France, more than any other ideological persuasion within the organised trade union movement in immediate pre-war and wartime Europe, can be seen to have constituted an authentic movement of opposition to the war in their refusal to subordinate class interests to those of the state, to endorse policies of ‘defencism’ of the ‘national interest’ and to abandon the rhetoric of class conflict. This article, which attempts to contribute to a much neglected comparative historiography of the international syndicalist movement, re-evaluates the syndicalist response across a broad geographical field of canvas (embracing France, Italy, Spain, Ireland, Britain and America) to reveal a rather more nuanced, ambiguous and uneven picture. -

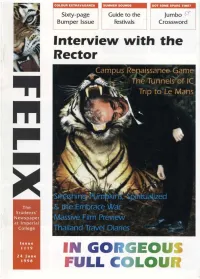

Felix Issue 1103, 1998

COLOUR EXTRAVAGANZA SUMMER SOUNDS GOT SOME SPARE TIME? Sixty-page Guide to the Jumbo $f Bumper Issue Festivals Crossword Interview with the Rector Campus Renaissance Game y the Tunnels "of IC 1 'I ^ Trip to Le Mans 7 ' W- & the Embrace War Massive Film Preview Thailand Travel Diaries IN GO EOUS FULL C 4 2 GAME 24 June 1998 24 June 1998 GAME 59 Automatic seating in Great Hall opens 1 9 18 unexpectedly during The Rector nicks your exam, killing fff parking space. Miss a go. Felix finds out that you bunged the builders to you're fc Rich old fo work Faster. "start small antiques shop. £2 million. Back one. ii : 1 1 John Foster electro- cutes himself while cutting IC Radio's JCR feed. Go »zzle all the Forward one. nove to the is. The End. P©r/-D®(aia@ You Bung folders to TTafeDts iMmk faster. 213 [?®0B[jafi®Drjfl 40 is (SoOOogj® gtssrjiBGariy tsm<s5xps@G(§tlI ITCD® esiDDorpo/Js Bs a DDD®<3CM?GII (SDB(Sorjaai„ (pAsasamG aracil f?QflrjTi@Gfi®OTjaD Y®E]'RS fifelaL rpDaecsS V®QO wafccs (MJDDD Haglfe G® sGairGo (SRBarjDDo GBa@to G® §GapG„ i You give the Sheffield building a face-lift, it still looks horrible. Conference Hey ho, miss a go. Office doesn't buy new flow furniture. ir failing Take an extra I. Move go. steps back. start Place one Infamou chunk of asbestos raer shopS<ee| player on this square, », roll a die, and try your Southsid luck at the CAMPUS £0.5 mil nuclear reactor ^ RENAISSANCE GAME ^ ill. -

Cat Smith MP Transforming Democracy Prem Sikka Industrial Strategy Dave Lister Academy Failures Plus Book & Film Reviews

#290 working_01 cover 27/12/2017 01:09 Page 1 CHARTIST For democratic socialism #290 January/February 2018 £2 Tories on thin ice John Palmer Peter Kenyon Brexit follies Mica Nava Sexual abuse Mary Southcott Cat Smith MP Transforming democracy Prem Sikka Industrial strategy Dave Lister Academy failures plus Book & Film reviews ISSN - 0968 7866 ISSUE www.chartist.org.uk #290 working_01 cover 27/12/2017 01:09 Page 2 Contributions and letters deadline for Editorial Policy CHARTIST #291 The editorial policy of CHARTIST is to promote debate amongst people active in 08 February 2018 radical politics about the contemporary Chartist welcomes articles of 800 or 1500 words, and relevance of democratic socialism across letters in electronic format only to: [email protected] the spectrum of politics, economics, science, philosophy, art, interpersonal Receive Chartist’s online newsletter: send your email address to [email protected] relations – in short, the whole realm of social life. Chartist Advert Rates: Our concern is with both democracy and socialism. The history of the last century Inside Full page £200; 1/2 page £125; 1/4 page £75; 1/8 page £40; 1/16 page £25; small box 5x2cm £15 single has made it abundantly clear that the sheet insert £50 mass of the population of the advanced We are also interested in advert swaps with other publications. To place an advert, please email: capitalist countries will have no interest [email protected] in any form of socialism which is not thoroughly democratic in its principles, its practices, its morality and its ideals. -

Secret Societies and the Easter Rising

Dominican Scholar Senior Theses Student Scholarship 5-2016 The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising Sierra M. Harlan Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Harlan, Sierra M., "The Power of a Secret: Secret Societies and the Easter Rising" (2016). Senior Theses. 49. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2016.HIST.ST.01 This Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POWER OF A SECRET: SECRET SOCIETIES AND THE EASTER RISING A senior thesis submitted to the History Faculty of Dominican University of California in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in History by Sierra Harlan San Rafael, California May 2016 Harlan ii © 2016 Sierra Harlan All Rights Reserved. Harlan iii Acknowledgments This paper would not have been possible without the amazing support and at times prodding of my family and friends. I specifically would like to thank my father, without him it would not have been possible for me to attend this school or accomplish this paper. He is an amazing man and an entire page could be written about the ways he has helped me, not only this year but my entire life. As a historian I am indebted to a number of librarians and researchers, first and foremost is Michael Pujals, who helped me expedite many problems and was consistently reachable to answer my questions. -

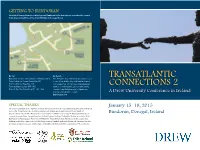

Transatlantic Connections 2 Confer - That He Made, and the Major Global and Transatlantic Projects He Is Currently Ence, 2015

GETTING TO BUNDORAN Located at Donegal’s most southerly point, Bundoran is the first stop as you enter the county from Sligo and Leitrim on the main N15 Sligo to Donegal Road. By Car By Coach Bundoran can be reached by the following routes: Bus Eireann’s Route 30 provides regular coach TRANSATLANTIC From Dublin via Cavan, Enniskillen N3 service from Dublin City and Dublin Airport From Dublin via Sligo N4 - N15 to Donegal. Get off the bus at Ballyshannon From Galway via Sligo N17 - N15 Station in County Donegal. Complimentary CONNECTIONS 2 From Belfast via Enniskillen M1 - A4 - A46 transfer from Ballyshannon to Bundoran; advanced booking necessary A Drew University Conference in Ireland buseireann.com SPECIAL THANKS Our sincere gratitude to the Institute of Study Abroad Ireland for its cooperation and partnership with Drew January 1 5–18, 2015 University. Many thanks also to Michael O’Heanaigh at Donegal County Council, Shane Smyth at Discover Bundoran, Martina Bromley and Joan Crawford at Failte Ireland, Gary McMurray for kind use of Bundoran, Donegal, Ireland cover photograph, Marc Geagan from North West Regional College, Tadhg Mac Phaidin and staff at Club Na Muinteori, Maura Logue, Marion Rose McFadden, Travis Feezell from University of the Ozarks, Tara Hoffman and Melvin Harmon at AFS USA, Kevin Lowery, Elizabeth Feshenfeld, Rebeccah Newman, Macken - zie Suess, and Lynne DeLade, all who made invaluable contributions to the organization of the conference. KEYNOTE SPEAKERS DON MULLAN “From Journey to Justice” Stories of Tragedy and Triumph from Bloody Sunday to the WWI Christmas Truces Thursday, 15 January • 8:30 p.m. -

Transporting Rebellion: How the Motorcar Shaped the Rising

Transporting Rebellion: How the motorcar shaped the Rising By Dr Leanne Blaney As motorcars sped members of the Secret Military Council towards Liberty Hall on Easter Sunday, few could have imagined that their next motor journey would be by military lorry – when their bodies were taken for burial to Arbour Hill after their execution. However, one obvious certainty – even among the confusion of Easter Sunday – was that motor vehicles, specifically the car would play a pivotal role during the upcoming Rising. Historiography relating to the Easter Rising tends to focus on the personalities, places and politics involved in the rebellion. Yet, we can gain a new perspective on the Rising, when we choose to assess more mundane aspects of the uprising. Understanding the role played by the motorcar as the Irish Volunteers prepared for the Rising and the manner in which cars were utilised by the British authorities and Irish civilians caught up in the six days of fighting alongside the Volunteers, allows us to recognise how the car acted as an agent for change during the conflict. By 1916, motorcars had become an accepted mainstay of Irish life for a variety of reasons. Firstly, they were relatively familiar sights on Irish roads. Two years earlier, in April 1914, the Irish Local Government Board had estimated that 19,554 motorised vehicles (predominantly motorcars and motorcycles) were registered within Ireland.1 While the outbreak of the First World War did witness a reduction in the number of motor vehicles registered on Irish roads as motorists and motor fuel became scarce, motorcars remained relatively plentiful, especially around Dublin. -

Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons War and Society (MA) Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-20-2019 Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising Sasha Conaway Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/war_and_society_theses Part of the Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Conaway, Sasha. Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising. 2019. Chapman University, MA Thesis. Chapman University Digital Commons, https://doi.org/10.36837/chapman.000079 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in War and Society (MA) Theses by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising A Thesis by Sasha Conaway Chapman University Orange, CA Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in War and Society May 2019 Committee in Charge Jennifer Keene, Ph.D., Chair Charissa Threat, Ph.D. John Emery, Ph. D. May 2019 Volunteer Women: Militarized Femininity in the 1916 Easter Rising Copyright © 2019 by Sasha Conaway iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my parents, Elda and Adam Conaway, for supporting me in pursuit of my master’s degree. They provided useful advice when tackling such a large project and I am forever grateful. I would also like to thank my advisor, Dr.