JOY DAMOUSI John Springthorpe’S War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship Australian Political Elites and Citizenship Education for `New Australians' 1945-1960 Patricia Anne Bernadette Jenkings Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Sydney MAY 2001 In memory of Bill Jenkings, my father, who gave me the courage and inspiration to persevere TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... i ABSTRACT................................................................................................................ iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. vi ABBREVIATIONS..................................................................................................vii LIST OF TABLES ..................................................................................................viii LIST OF FIGURES................................................................................................. ix INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................... 1 Theoretical Orientation ................................................................................... 9 Methodological Framework.......................................................................... 19 CHAPTER ONE-POLITICAL ELITES, POST-WAR IMMIGRATION AND THE QUESTION OF CITIZENSHIP .... 28 Introduction........................................................................................................ -

A New Era Begins

Edition 129 • April 2017 TheLion Wesley College Community Magazine A new era begins... Features: From Wesley's past to Framing the Future | A long life well lived | New role for our new residence A True Education Contents Editorial Editorial ............................................ 2 I don’t receive a lot of feedback through the mail, but last year I received a letter to which I did not reply at the time, because the issue it Principal's lines ................................. 3 dealt with needs, I think, a public response. In essence, it drew attention to how we select material for this magazine. The letter was not in any way Features antagonistic – in fact, the tone was courteous, respectful and full of goodwill 2016 Scholars and Duces ............ 5 towards what we seek to achieve in this publication – but pointed towards a publishing conundrum I have felt as well. Let me share a few extracts: Academic Excellence 2016 .......... 6 From Wesley's past to While most assuredly the reports of past students who are “high achievers”… Framing the Future ...................... 7 are certainly well merited…these would number possibly 25% of the student body over the many years of Wesley…There appears to be little recognition A long life well lived ..................... 9 attributed to, or acknowledgement of, the greater number who make up the New role for our remaining 75%. new residence ............................. 10 Australia Day honours 2017 ......... 11 These students equally absorbed the “Wesley spirit” (there’s no disputing that) which very clearly encouraged them…From this group came the doctors, solicitors, accountants, all other professions, merchants, farmers, ............... 12 College Snapshots tradesmen etc. -

Eliminating the Drudge Work”: Campaigning for University- Based Nursing Education in Australia, 1920-1935

Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées en formation infirmière Volume 6 Issue 2 The History of Nursing Education | L’histoire Article 7 de la formation en sciences infirmières “Eliminating the drudge work”: Campaigning for university- based nursing education in Australia, 1920-1935 Madonna Grehan Dr University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://qane-afi.casn.ca/journal Part of the Australian Studies Commons, Education Commons, History Commons, and the Nursing Commons Recommended Citation Grehan, Madonna Dr (2020) "“Eliminating the drudge work”: Campaigning for university-based nursing education in Australia, 1920-1935," Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées en formation infirmière: Vol. 6: Iss. 2, Article 7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17483/2368-6669.1254 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées en formation infirmière. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées en formation infirmière by an authorized editor of Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées en formation infirmière. “Eliminating the drudge work”: Campaigning for university-based nursing education in Australia, 1920-1935 Cover Page Footnote Acknowledgements: Thanks to the University of Melbourne Archives and two anonymous reviewers of this article. Remerciements : Merci aux archives de la University of Melbourne et aux deux réviseurs anonymes de cet article. This article is available in Quality Advancement in Nursing Education - Avancées en formation infirmière: https://qane- afi.casn.ca/journal/vol6/iss2/7 Grehan: “eliminating the drudge work”: campaigning for university-based nursing education in Australia, 1920-1935 Background For most of the twentieth century in Australia, hospital-based apprenticeship programs were the only pathway leading to registration as a nurse or midwife. -

Australia: a Cultural History (Third Edition)

AUSTRALIA A CULTURAL HISTORY THIRD EDITION JOHN RICKARD AUSTRALIA Australia A CULTURAL HISTORY Third Edition John Rickard Australia: A Cultural History (Third Edition) © Copyright 2017 John Rickard All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/ach-9781921867606.html Series: Australian History Series Editor: Sean Scalmer Design: Les Thomas Cover image: Aboriginal demonstrators protesting at the re-enactment of the First Fleet. The tall ships enter Sydney Harbour with the Harbour Bridge in the background on 26 January 1988 during the Bicentenary celebrations. Published in Sydney Morning Herald 26 January, 1988. Courtesy Fairfax Media Syndication, image FXJ24142. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Creator: Rickard, John, author. Title: Australia : a cultural history / John Rickard. Edition: Third Edition ISBN: 9781921867606 (paperback) Subjects: Australia--History. Australia--Civilization. Australia--Social conditions. ISBN (print): 9781921867606 ISBN (PDF): 9781921867613 First published 1988 Second edition 1996 In memory of John and Juan ABOUT THE AUTHOR John Rickard is the author of two prize-winning books, Class and Politics: New South Wales, Victoria and the Early Commonwealth, 1890-1910 and H.B. -

Six Problems in the Biography of Alfred Deakin

Six Problems in the Biography of Alfred Deakin William Coleman1 Judith Brett’s The Enigmatic Mr Deakin constitutes the fifth biographical study of Alfred Deakin. It succeeds the admiring salute of Murdoch (1999 [1923]), the inscriptional chronicle of La Nauze (1965), the revelatory exposé of Gabay (1992) and the waggish sallies of Rickard (1996). We now have Brett’s full-length portrait of the man, in all his parts (Brett, 2017). But the topic of Alfred Deakin will not be exhausted by even this attention. Let me nominate six problems that remain for future biographers to puzzle over. 1. Deakin’s spiritualism Deakin was a committed spiritualist. Contemporary observers—you and me—are baffled by how Deakin could so readily soak up such twaddle. His biographers have sought to reconcile his spiritualism into our own understanding by means of two strategies. Both are ‘apologetic’ in some measure. 1. Minimisation. Murdoch and La Nauze present Deakin’s spiritualism as a youthful jeu d’esprit. This contention, however, became untenable with the remarkable disclosures of Gabay. And Brett has reinforced Gabay with further details of how much Deakin’s spiritualist activities extended into his maturity. As late as 1891—the same year he was a delegate at the Federation Convention— Deakin was seeking guidance from the séances of the dubious Mrs Cohen. 2. Rationalisation in terms of rationality. Gabay and Brett are inclined to present spiritualism as a wayward progeny of the conquering rationalism of Deakin’s 1 College of Business and Economics, The Australian National University, [email protected]. -

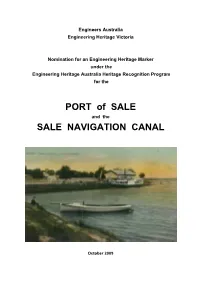

HRP.Port of Sale.Nomination.Oct 2009

Engineers Australia Engineering Heritage Victoria Nomination for an Engineering Heritage Marker under the Engineering Heritage Australia Heritage Recognition Program for the PORT of SALE and the SALE NAVIGATION CANAL October 2009 2 Caption for Cover Photograph The photograph is a reproduction from a postcard showing the paddle steamer PS Dargo moored at a wharf in the Swinging Basin at the Port of Sale. The date is not recorded. The postcard is apparently based on a hand-tinted black and white photograph. ©State Library of Victoria reference a907729 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Heritage Award Nomination Form 5 Heritage Assessment 6 1 Basic Data 6 1.1 Item Name ` 6 1.2 Other/Former Name 6 1.3 Location 6 1.4 Address 6 1.5 Suburb/Nearest Town 6 1.6 State 6 1.7 Local Government Area 6 1.8 Owner 6 1.9 Current Use 6 1.10 Former use 6 1.11 Designer 6 1.12 Maker/Builder 6 1.13 Year Started 6 1.14 Year completed 6 1.15 Physical Description 6 1.16 Physical Condition 7 1.17 Modifications and Dates 7 1.18 Historical Notes 7 1.19 Heritage Listings 12 1.20 Associated Nomination 12 2 Assessment of Significance 13 2.1 Historical Significance 13 2.2 Historic Individuals or Associations 13 2.2.1 Angus McMillan 13 2.2.2 Paul Edmund Strzelecki 13 2.2.3 Sir John Coode 15 2.2.4 Alfred Deakin 16 2.3 Creative of Technical Achievement 20 4 2.4 Research Potential 23 2.5 Social 23 2.6 Rarity 23 2.7 Representativeness 23 2.8 Integrity/Intactness 24 2.9 Statement of Significance 24 2.10 Area of Significance 25 3 Marking and Interpretation 26 4 References 27 Attachment 1 28 Maps of the Port of Sale and the Sale Navigation Canal Attachment 2 29 Historic Drawings of Port of Sale and the Sale Navigation Canal Attachment 3 31 Images of the Port of Sale and the Sale Navigation Canal 5 Heritage Award Nomination Form The Administrator Engineering Heritage Australia Engineers Australia Engineering House 11 National Circuit BARTON ACT 2600 Name of work : Port of Sale and the Sale Navigation Canal The above-mentioned work is nominated to be awarded an Engineering Heritage Marker. -

ANNETTE SOUMILAS ‘I Was the State of Victoria’: Jessie Clarke’S 1934 Pageant of Nations Costume

76 ANNETTE SOUMILAS ‘I was the State of Victoria’: Jessie Clarke’s 1934 Pageant of Nations costume In 1998, Jessie Clarke donated to State Library Victoria the costume she wore as 20-year-old Jessie Brookes in the Pageant of Nations extravaganza during Victoria’s centenary celebrations of 1934 and 1935.1 The donation included a hand-painted skirt, two hooped petticoats and a long, flowing, green velvet cloak veined with glittering silver overlay. She also gave to the Library a hand- coloured studio portrait depicting her wearing the costume, which showed that the skirt had been worn with a shimmering silver bodice, over which trailed the cloak, and the costume had been crowned by a headdress made from silver metallic materials.2 Unfortunately, the headdress and bodice had been destroyed in the Ash Wednesday fires of 1983.3 Little was known about the costume when I first saw it at State Library Victoria in 2013. Who had designed it and why? What did the scenes painted around the skirt and the headdress represent? The story of the costume has been rediscovered through researching manuscripts, photographs and ephemera in the Library’s collection. Victoria’s centenary celebrations The centenary celebrations marked 100 years of white settlement of Victoria. Beginning in Portland, on the state’s southwest coast, in October 1934, they featured a visit by Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, and ran through to June Jessie Brookes wearing the ‘State of Victoria’ gown for the Pageant of Nations gala events, Victorian Centenary Celebrations, c. 1934. Photograph by Broothorn Studios. Jessie Clarke Papers, MS 13268 ‘I was the State of Victoria’ 77 78 The La Trobe Journal No. -

Notes,La Trobe Journal No. 96 September

196 Notes Abbreviations 9 See Military and Naval Defence of the Empire, ADB = Australian Dictionary of Biography Wellington: Govt. Printer, 1909, p. 32. (available on-line at http://adb.anu.edu.au). 10 See ‘Part I – Recommendations. Strategical AWM = Australian War Memorial considerations’, Points 4 and 5, Kitchener, Bean: Charles Bean (ed.), Official History of ‘Memorandum on the defence of Australia’, Australia in the War of 1914–1918, 12 vols. A463, 1957/1059, NAA. CUP = Cambridge University Press 11 Committee of Imperial Defence, Minutes of the MUP = Melbourne University Press 112th Meeting, 29 May 1911, 12, 16–17, 25, 27, NAA = National Archives of Australia CAB 38/18/41, The National Archives, London NLA = National Library of Australia (TNA). OUP = Oxford University Press 12 Mordike was the first historian to stress the SLNSW = State Library of New South Wales significance of this in Australian military SLV = State Library of Victoria historiography. See ‘Operations of defence UMA = University of Melbourne Archives (military) – 2nd day, 17 June 1911’, WO 106/43, UQP = University of Queensland Press TNA, quoted in John Mordike, ‘We Should Do This Thing Quietly’: Japan and the Great Newton: ‘We have sprung at a bound’ Deception in Australian Defence Policy, 1911– 1 Joseph Cook, Pocket Diary for 1915, entry on 1914, Fairburn, ACT: Aerospace Centre, 2002, memoranda pages, Cook Papers, M3580, 7, pp. 53–79. See also ‘Report of a committee of NAA. the imperial conference convened to discuss 2 Charles Bean contrasted Australia’s desire defence (military) at the War Office, 14th and 17th June, 1911’, in Papers Laid Before the to be ‘straight’ with Britain’s wavering (The Imperial Conference, 1911, Dealing with Naval Story of Anzac from the Outbreak of War to the and Military Defence, Wellington: Govt Printer, End of the First Phase of the Gallipoli Campaign, 1912, pp. -

The Federal Story the Inner History of the Federal Cause 1880-1900

The Federal Story The Inner History of the Federal Cause 1880-1900 Deakin, Alfred (1856-1919) Edited by J. A. La Nauze A digital text sponsored by New South Wales Centenary of Federation Committee University of Sydney Library Sydney 2000 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/fed/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by Melbourne University Press Melbourne 1963 The work by J. A. La Nauze is reproduced here in electronic form with the kind permission of Barbara La Nauze, 21 September 2000. All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1944 Languages: French Italian Latin 342.94/D Australian Etexts autobiographies political history 1910-1939 prose nonfiction federation 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing The Federal Story The Inner History of the Federal Cause 1880-1900 Melbourne Melbourne University Press 1963 (1944) Introduction J. A. La Nauze Alfred Deakin died in 1919. His ‘Inner History of the Federal Cause’ was first published in 1944 by Messrs Robertson and Mullens of Melbourne, in an edition edited by his son-in-law, Herbert Brookes, who gave it the title of The Federal Story. The present edition, published with the permission of Mr and Mrs Brookes, has been newly collated with the manuscript, passages omitted from the 1944 edition have been restored, and new material has been added. -

Striving for National Fitness

STRIVING FOR NATIONAL FITNESS EUGENICS IN AUSTRALIA 1910s TO 1930s Diana H Wyndham A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Sydney July 1996 Abstract Striving For National Fitness: Eugenics in Australia, 1910s to 1930s Eugenics movements developed early this century in more than 20 countries, including Australia. However, for many years the vast literature on eugenics focused almost exclusively on the history of eugenics in Britain and America. While some aspects of eugenics in Australia are now being documented, the history of this movement largely remained to be written. Australians experienced both fears and hopes at the time of Federation in 1901. Some feared that the white population was declining and degenerating but they also hoped to create a new utopian society which would outstrip the achievements, and avoid the poverty and industrial unrest, of Britain and America. Some responded to these mixed emotions by combining notions of efficiency and progress with eugenic ideas about maximising the growth of a white population and filling the 'empty spaces'. It was hoped that by taking these actions Australia would avoid 'racial suicide' or Asian invasion and would improve national fitness, thus avoiding 'racial decay' and starting to create a 'paradise of physical perfection'. This thesis considers the impact of eugenics in Australia by examining three related propositions: • that from the 1910s to the 1930s, eugenic ideas in Australia were readily accepted because of concerns about the declining birth rate • that, while mainly derivative, Australian eugenics had several distinctly Australian qualities • that eugenics has a legacy in many disciplines, particularly family planning and public health This examination of Australian eugenics is primarily from the perspective of the people, publications and organisations which contributed to this movement in the first half of this century. -

III. the Pro-Hitler, Fascist Origins of the Liberal Party

The New Citizen April 2004 Page 29 Defeat the Synarchists—Fight for a National Bank III. The Pro-Hitler, Fascist Origins of the Liberal Party THE 1930’s SYNARCHIST ASSAULT In this section The 1930s Synarchist Assault on Australia Jack Lang and Frank Anstey on the Synarchy ON AUSTRALIA The “Red Menace” and the Fascist “Citizens “And therefore, the essential conflict is between the national interest and the Leagues” The Stormtroopers—I: The League for National financiers. Hitler was not a creation of a bunch of dummies in brown uniforms. Hitler Security was the creation of bankers… The Collins House Group “The bankers of this type, the private bankers, created Hitler, because there was a Herbert Brookes and the Secret Armies financial crisis, and under conditions of financial crisis, if the government is The Stormtroopers—II: The Old Guard and the accountable to the people, it is the bankers that will pay, not the people. And therefore, New Guard the bankers say, “It’s the people, it’s the government, that has to go.” –Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., December 16, 2003 The Liberal Party: The New Face of Synarchism The Synarchy’s Political Parties The Lying Mass Media nglo-Dutch parliamentary Robert Gordon Menzies: Would-be Petain of Asystems are a puppet show, in Britain which the strings are held by cen- The “New Liberalism”: The Old Fascism tral banks, which in turn are con- Friedrich von Hayek, Founding Father of the Liberal trolled by a cabal of private finan- Party ciers. In times of crisis, these pri- “The Association”: Old Guard and LNS Regroup vate financiers destabilise the par- liamentary systems, and replace Postwar Fascism: The Mont Pelerin Society them either with parliaments that Mont Pelerin’s Puppets: Liberal and Labor will bow to their interests, or even, The Macquarie Bank as happened in much of Europe The MPS Think Tanks during the 1930s, with outright Liberal Party Funding fascist regimes.