Victorian Historical Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Cuthbert's Trail

St Cuthbert’s Trail St Cuthbert’s Bayside Architectural Trail 3 Trail Architectural Bayside Get the Bayside Walks & Trails App Distance: Distance: Brighton Bay Street Undulations: 2.8kms Gentle Walking Time: Walking 76 Royal Avenue, Sandringham PO Box 27 Sandringham VIC 3191 T (03) 9599 4444 [email protected] 50mins www.bayside.vic.gov.au 500 Metres September 2013 1 Former ES&A Bank Address 279 Bay St, Brighton (cnr Asling St) Bayside Architecutral Trail Style Gothic Revival Trail 3 Architects Terry & Oakden Property 1 Date 1882 Other name: ANZ Bank The steeply sloped roof has gabled ends capped with unpainted cement render. Window and door heads are painted and finished with cement render portico projects A small motifs. flower with adorned from the symmetric façade and contains the word ‘Bank’ embossed on either side, with other text formed in these rendered panels. Brighton’s was first the English bank1874 in Scottish & Australian Bank (ES&A), which merged with the The ANZ ES&A in 1970. Bank, first established moved into this building in 1874, in It functioned1882. in its intended fashion until 2002. ES&A were known for their series of banks in the Gothic Revival style, many designed by William Wardell, who also designed the ES&A head office, the Gothic Bank, in Collins St, Melbourne This(1883). branch is another example of that style, brick. tuck-pointed in executed The North Brighton branch of the Commercial Bank was the second bank in Brighton and rented a building on the corner of Bay and Cochrane Streets when it opened in The 1883. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 89, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2018 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Judith Smart and Richard Broome (Editors, Victorian Historical Journal) Jill Barnard Rozzi Bazzani Sharon Betridge (Co-editor, History News) Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) (Co-Editor, History News) Marie Clark Jonathan Craig (Review Editor) Don Garden (President, RHSV) John Rickard Judith Smart Lee Sulkowska Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 290 VOLUME 89, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2018 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2018 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

Imagereal Capture

THE FOUNDATION OF THE MONASH LAW SCHOOL PETER BALMFORD* INTRODUCTION From 1853 to 1878, an Englishman named John Hughes Clayton practised as a solicitor in the City of Melbourne.' At the end of the working day, he was usually driven home by his coachman: a journey of about twelve miles to his property in a district known as "Old Dam~er".~In the course of time, the north-south road running past his property came to be called "Clayton's Road": the name was ultimately shortened to Clayton Road and from it derived the present name of the di~trict.~ Clayton had become a suburb of Melbourne long before 1958, when Mon- ash University was established by legislation of the Victorian Parliament.4 Nevertheless, the Interim Council of the new University was able to find there 250 acres of largely vacant land which it chose as the site on which to build.5 Sir John Monash (1865-1931), after whom the University was named, is celebrated as a soldier, as an engineer and as an administrator. He was a graduate of the University of Melbourne in Arts, Engineering and Law. He never practised as a barrister or solicitor, although, in the 1890s and the early years of the twentieth century, he appeared as an advocate in arbitrations on engineering disputes and frequently gave evidence as an expert witness in engineering and patent mattem6 This article gives an account of the foundation of the law school at Monash University, Clayton, in celebration of the twenty-five years of teaching which have now been completed. -

Anzac Day 2015

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2014-15 UPDATED 16 APRIL 2015 Anzac Day 2015 David Watt Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section This ‘Anzac Day Kit’ has been compiled over a number of years by various staff members of the Parliamentary Library, and is updated annually. In particular the Library would like to acknowledge the work of John Moremon and Laura Rayner, both of whom contributed significantly to the original text and structure of the Kit. Nathan Church and Stephen Fallon contributed to the 2015 edition of this publication. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 What is this kit? .................................................................................................. 4 Section 1: Speeches ..................................................................................... 4 Previous Anzac Day speeches ............................................................................. 4 90th anniversary of the Anzac landings—25 April 2005 .................................... 4 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier............................................................................ 5 Ataturk’s words of comfort ................................................................................ 5 Section 2: The relevance of Anzac ................................................................ 5 Anzac—legal protection ..................................................................................... 5 The history of Anzac Day ................................................................................... -

Kelson Nor Mckernan

Vol. 5 No. 9 November 1995 $5.00 Fighting Memories Jack Waterford on strife at the Memorial Ken Inglis on rival shrines Great Escapes: Rachel Griffiths in London, Chris McGillion in America and Juliette Hughes in Canberra and the bush Volume 5 Number 9 EURE:-KA SJRE:i:T November 1995 A magazine of public affairs, the arts and th eology CoNTENTS 4 30 COMMENT POETRY Seven Sketches by Maslyn Williams. 9 CAPITAL LETTER 32 BOOKS 10 Andrew Hamilton reviews three recent LETTERS books on Australian immigration; Keith Campbell considers The Oxford 12 Companion to Philosophy (p36); IN GOD WE BUST J.J.C. Smart examines The Moral Chris McGillion looks at the implosion Pwblem (p38); Juliette Hughes reviews of America from the inside. The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen Vol I and Hildegard of Bingen and 14 Gendered Theology in Ju dea-Christian END OF THE GEORGIAN ERA Tradition (p40); Michael McGirr talks Michael McGirr marks the passing of a to Hugh Lunn, (p42); Bruce Williams Melbourne institution. reviews A Companion to Theatre in Australia (p44); Max T eichrnann looks 15 at Albert Speer: His Battle With Truth COUNTERPOINT (p46); James Griffin reviews To Solitude The m edia's responsibility to society is Consigned: The Journal of William m easured by the code of ethics, says Smith O'BTien (p48). Paul Chadwick. 49 17 THEATRE ARCHIMEDES Geoffrey Milne takes a look at quick changes in W A. 18 WAR AT THE MEMORIAL 51 Ja ck Waterford exarnines the internal C lea r-fe Jl ed forest area. Ph oto FLASH IN THE PAN graph, above left, by Bill T homas ructions at the Australian War Memorial. -

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

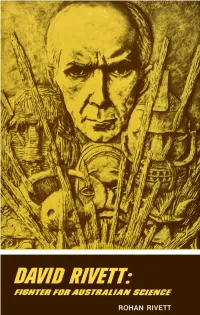

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

The Patrician and the Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the Making of Australian History

128 New Zealand Journal of History, 42, 1 (2008) The Patrician and the Bloke: Geoffrey Serle and the Making of Australian History. By John Thompson. Pandanus Books, Canberra, 2006. xix, 383pp. Australian price: $34.95. ISBN 1-74076-152-9. THE LIKELY INTEREST FOR READERS OF THIS JOURNAL in this book is that Geoffrey Serle (1922–1998) helped to pioneer Australian historiography in much the way that Keith Sinclair prompted and promoted a ‘nationalist’ New Zealand historiography. Rather than submitting to the cultural cringe and seeing their respective countries’ pasts in imperial and British contexts, Serle and Sinclair treated them as histories in their own right. Brought up in Melbourne, Serle was a Rhodes Scholar who returned to the University of Melbourne in 1950 to teach Australian history following the departure of Manning Clark to Canberra University College. The flamboyant Clark is generally seen as the father of Australian historiography and Serle has been somewhat cast in his shadow. Yet Serle’s contribution to Australian historiography was arguably more solid. As well as undergraduate teaching, postgraduate supervision and his writing there was the institutional work: his efforts on behalf of the proper preservation and administration of public archives, his support of libraries and art galleries, the long-term editorship of Historical Studies (1955–1963), and co-editorship then sole editorship of the Australian Dictionary of Biography (1975–1988). Clark was a creative spirit, turbulent and in the public gaze. The unassuming Serle was far more oriented towards the discipline. The book’s title derives from ‘the streak of elitism in Geoffrey Serle sitting in apparent contradiction with himself as “ordinary” Australian, easygoing, democratic, laconic’ (p.9, see also p.303, n.40). -

Reluctant Lawyer, Reluctant Politician

Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) Australia’s 2nd Prime Minister Terms of office 24 September 1903 to 27 April 1904 • 5 July 1905 to 13 November 1908 • 2 June 1909 to 29 April 1910 Reluctant lawyer, reluctant politician Deakin first met David Syme, the Scottish-born owner of The Age newspaper, in May 1878, as the result of their mutual interest in spiritualism. Soon after, Syme hired the reluctant lawyer on a trial basis, and he made an immediate impression. Despite repeatedly emphasising how ‘laborious’ journalism could be, Deakin was good at it, able to churn out leaders, editorials, investigative articles and reviews as the occasion demanded. Syme wielded enormous clout, able to make and break governments in colonial Victoria and, after 1901, national governments. A staunch advocate of protection for local industry, he ‘connived’ at Deakin’s political education, converting his favourite young journalist, a free-trader, into a protectionist. As Deakin later acknowledged, ‘I crossed the fiscal Rubicon’, providing a first clear indication of his capacity for political pragmatism--his willingness to reshape his beliefs and ‘liberal’ principles if and when the circumstances required it. Radical MLA David Gaunson dismissed him as nothing more than a ‘puppet’, ‘the poodle dog of a newspaper proprietor’. Syme was the catalyst for the start of Deakin’s political career in 1879-80. After two interesting false starts, Deakin was finally elected in July 1880, during the same year that a clairvoyant predicted he would soon embark on a life-changing journey to London to participate in a ‘grand tribunal’. Deakin did not forget what he described as ‘extraordinary information’, and in 1887 he represented Victoria at the Colonial Conference in London. -

The University Tea Room: Informal Public Spaces As Ideas Incubators Claire Wright University of Wollongong, [email protected]

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts 2018 The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators Claire Wright University of Wollongong, [email protected] Simon Ville University of Wollongong, [email protected] Publication Details Wright, C. & Ville, S. (2018). The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators. History Australia, 15 (2), 236-254. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators Abstract Informal spaces encourage the meeting of minds and the sharing of ideas. They es rve as an important counterpoint to the formal, silo-like structures of the modern organisation, encouraging social bonds and discussion across departmental lines. We address the role of one such institution – the university tea room – in Australia in the post-WWII decades. Drawing on a series of oral history interviews with economic historians, we examine the nature of the tea room space, demonstrate its effects on research within universities, and analyse the causes and implications of its decline in recent decades. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Law Publication Details Wright, C. & Ville, S. (2018). The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators. History Australia, 15 (2), 236-254. This journal article is available at Research -

Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria

Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Stuart E. Dawson Department of History, Monash University Ned Kelly and the Myth of a Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Dr. Stuart E. Dawson Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs Published by Dr. Stuart E. Dawson, Adjunct Research Fellow, Department of History, School of Philosophical, Historical and International Studies, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, 3800. Published June 2018. ISBN registered to Primedia E-launch LLC, Dallas TX, USA. Copyright © Stuart Dawson 2018. The moral right of the author has been asserted. Author contact: [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-64316-500-4 Keywords: Australian History Kelly, Ned, 1855-1880 Kelly Gang Republic of North-Eastern Victoria Bushrangers - Australia This book is an open peer-reviewed publication. Reviewers are acknowledged in the Preface. Inaugural document download host: www.ironicon.com.au Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs This book is a free, open-access publication, and is published under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence. Users including libraries and schools may make the work available for free distribution, circulation and copying, including re-sharing, without restriction, but the work cannot be changed in any way or resold commercially. All users may share the work by printed copies and/or directly by email, and/or hosting it on a website, server or other system, provided no cost whatsoever is charged. Just print and bind your PDF copy at a local print shop! (Spiral-bound copies with clear covers are available in Australia only by print-on-demand for $199.00 per copy, including registered post.