Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) Australia’S Second Prime Minister

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St Cuthbert's Trail

St Cuthbert’s Trail St Cuthbert’s Bayside Architectural Trail 3 Trail Architectural Bayside Get the Bayside Walks & Trails App Distance: Distance: Brighton Bay Street Undulations: 2.8kms Gentle Walking Time: Walking 76 Royal Avenue, Sandringham PO Box 27 Sandringham VIC 3191 T (03) 9599 4444 [email protected] 50mins www.bayside.vic.gov.au 500 Metres September 2013 1 Former ES&A Bank Address 279 Bay St, Brighton (cnr Asling St) Bayside Architecutral Trail Style Gothic Revival Trail 3 Architects Terry & Oakden Property 1 Date 1882 Other name: ANZ Bank The steeply sloped roof has gabled ends capped with unpainted cement render. Window and door heads are painted and finished with cement render portico projects A small motifs. flower with adorned from the symmetric façade and contains the word ‘Bank’ embossed on either side, with other text formed in these rendered panels. Brighton’s was first the English bank1874 in Scottish & Australian Bank (ES&A), which merged with the The ANZ ES&A in 1970. Bank, first established moved into this building in 1874, in It functioned1882. in its intended fashion until 2002. ES&A were known for their series of banks in the Gothic Revival style, many designed by William Wardell, who also designed the ES&A head office, the Gothic Bank, in Collins St, Melbourne This(1883). branch is another example of that style, brick. tuck-pointed in executed The North Brighton branch of the Commercial Bank was the second bank in Brighton and rented a building on the corner of Bay and Cochrane Streets when it opened in The 1883. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 89, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2018 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. The Victorian Historical Journal is a fully refereed journal dedicated to Australian, and especially Victorian, history produced twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Judith Smart and Richard Broome (Editors, Victorian Historical Journal) Jill Barnard Rozzi Bazzani Sharon Betridge (Co-editor, History News) Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) (Co-Editor, History News) Marie Clark Jonathan Craig (Review Editor) Don Garden (President, RHSV) John Rickard Judith Smart Lee Sulkowska Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 290 VOLUME 89, NUMBER 2 DECEMBER 2018 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2018 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

Justice Richard O'connor and Federation Richard Edward O

1 By Patrick O’Sullivan Justice Richard O’Connor and Federation Richard Edward O’Connor was born 4 August 1854 in Glebe, New South Wales, to Richard O’Connor and Mary-Anne O’Connor, née Harnett (Rutledge 1988). The third son in the family (Rutledge 1988) to a highly accomplished father, Australian-born in a young country of – particularly Irish – immigrants, a country struggling to forge itself an identity, he felt driven to achieve. Contemporaries noted his personable nature and disarming geniality (Rutledge 1988) like his lifelong friend Edmund Barton and, again like Barton, O’Connor was to go on to be a key player in the Federation of the Australian colonies, particularly the drafting of the Constitution and the establishment of the High Court of Australia. Richard O’Connor Snr, his father, was a devout Roman Catholic who contributed greatly to the growth of Church and public facilities in Australia, principally in the Sydney area (Jeckeln 1974). Educated, cultured, and trained in multiple instruments (Jeckeln 1974), O’Connor placed great emphasis on learning in a young man’s life and this is reflected in the years his son spent attaining a rounded and varied education; under Catholic instruction at St Mary’s College, Lyndhurst for six years, before completing his higher education at the non- denominational Sydney Grammar School in 1867 where young Richard O’Connor met and befriended Edmund Barton (Rutledge 1988). He went on to study at the University of Sydney, attaining a Bachelor of Arts in 1871 and Master of Arts in 1873, residing at St John’s College (of which his father was a founding fellow) during this period. -

Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention

The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention The Art of Consensus: Edmund Barton and the 1897 Federal Convention* Geoffrey Bolton dmund Barton first entered my life at the Port Hotel, Derby on the evening of Saturday, E13 September 1952. As a very young postgraduate I was spending three months in the Kimberley district of Western Australia researching the history of the pastoral industry. Being at a loose end that evening I went to the bar to see if I could find some old-timer with an interesting store of yarns. I soon found my old-timer. He was a leathery, weather-beaten station cook, seventy-three years of age; Russel Ward would have been proud of him. I sipped my beer, and he drained his creme-de-menthe from five-ounce glasses, and presently he said: ‘Do you know what was the greatest moment of my life?’ ‘No’, I said, ‘but I’d like to hear’; I expected to hear some epic of droving, or possibly an anecdote of Gallipoli or the Somme. But he answered: ‘When I was eighteen years old I was kitchen-boy at Petty’s Hotel in Sydney when the federal convention was on. And every evening Edmund Barton would bring some of the delegates around to have dinner and talk about things. I seen them all: Deakin, Reid, Forrest, I seen them all. But the prince of them all was Edmund Barton.’ It struck me then as remarkable that such an archetypal bushie, should be so admiring of an essentially urban, middle-class lawyer such as Barton. -

Some Aspects of the Federal Political Career of Andrew Fisher

SOME ASPECTS OF THE FEDERAL POLITICAL CAREER OF ANDREW FISHER By EDWARD WIL.LIAM I-IUMPHREYS, B.A. Hans. MASTER OF ARTS Department of History I Faculty of Arts, The University of Melbourne Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degr'ee of Masters of Arts (by Thesis only) JulV 2005 ABSTRACT Andrew Fisher was prime minister of Australia three times. During his second ministry (1910-1913) he headed a government that was, until the 1940s, Australia's most reformist government. Fisher's second government controlled both Houses; it was the first effective Labor administration in the history of the Commonwealth. In the three years, 113 Acts were placed on the statute books changing the future pattern of the Commonwealth. Despite the volume of legislation and changes in the political life of Australia during his ministry, there is no definitive full-scale biographical published work on Andrew Fisher. There are only limited articles upon his federal political career. Until the 1960s most historians considered Fisher a bit-player, a second ranker whose main quality was his moderating influence upon the Caucus and Labor ministry. Few historians have discussed Fisher's role in the Dreadnought scare of 1909, nor the background to his attempts to change the Constitution in order to correct the considered deficiencies in the original drafting. This thesis will attempt to redress these omissions from historical scholarship Firstly, it investigates Fisher's reaction to the Dreadnought scare in 1909 and the reasons for his refusal to agree to the financing of the Australian navy by overseas borrowing. -

Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915

5 Andrew FISHER, PC Prime Minister 13 November 1908 to 2 June 1909; 29 April 1910 to 24 June 1913; 17 September 1914 to 27 October 1915. Andrew Fisher became the 5th prime minister when the Liberal- Labor coalition government headed by Alfred Deakin collapsed due to loss of parliamentary Labor support. Fisher’s first period as prime minister ended when the new Fusion Party of Deakin and Joseph Cook defeated the government in parliament. His second term resulted from an overwhelming Labor victory at elections in 1910. However, Labor lost power by one seat at the 1913 elections. Fisher was prime minister again in 1914, as a result of a double-dissolution election. Fisher resigned from office in October 1915, his health affected by the pressures of political life. Member of the Australian Labor Party c1901-28. Member of the House of Representatives for the seat of Wide Bay (Queensland) 1901-15; Minister for Trade and Customs 1904; Treasurer 1908-09, 1910-13, 1914-15. Main achievements (1904-1915) Under his prime ministership, the Commonwealth Government issued its first currency which replaced bank and State currency as the only legal tender. Also, the Commonwealth Bank was established. Strengthened the Conciliation and Arbitration Act. Introduced a progressive land tax on unimproved properties. Construction began on the trans-Australian railway, linking Port Augusta and Kalgoorlie. Established the Australian Capital Territory and brought the Northern Territory under Commonwealth control. Established the Royal Australian Navy. Improved access to invalid and aged pensions and brought in maternity allowances. Introduced workers’ compensation for federal public servants. -

Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1

10 Australian Historians Networking, 1914–1973 Geoffrey Bolton1 TheOxford English Dictionary defines networking as ‘the action or process of making use of a network of people for the exchange of information, etc., or for professional or other advantage’.2 Although recently prominent in management theory, the art of networking has been practised over many centuries in many societies, but its role in the Australian academic community has been little explored. This essay represents a preliminary excursion into the field, raising questions that more systematic researchers may follow in time, and drawing unashamedly on the resources of the Australian Dictionary of Biography. Beginning on the eve of the First World War, the essay is bounded by the formation of the Australian Historical Association in 1973, at which date the profession provided itself with 1 This essay is a lightly edited version of the paper prepared by Geoffrey Bolton for the ‘Workshop on Biographies and Autobiographies of Historians’ held at The Australian National University in July 2015. Professor Bolton had intended to make further revisions, which included adding some analysis of the social origins of the Australian historians who participated in the networks he had defined. In all essential respects, however, we believe that the essay as presented here would have met with his approval, and we are very grateful to Carol Bolton for giving permission to make the modest editorial changes that we have incorporated. For biographical information and insights, see Stuart Macintyre, Lenore Layman and Jenny Gregory, eds, A Historian for all Seasons: Essays for Geoffrey Bolton (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2017). -

Personal Injury Law 2011

Event pricing (please tick your selection) EXAMPLE One day conference 1 $ 900 + GST = $ 990 $990 Personal Injury Law 2011 Essential strategies and case law updates for assessing and managing injury claims 16 November 2011, The Grace Hotel Sydney 23 November 2011, Stamford Plaza Melbourne Speakers Sydney: • The Honourable Justice Margaret Beazley AO, New Program highlights South Wales Court of Appeal • Richard Seton SC, Barrister, Maurice Byers Chambers • Interpretation of Section 5D of the Civil Liability Act in Personal Injury Cases • Kellie Edwards, Barrister, Denman Chambers • Raj Kanhai, Long Tail Claims Manager, QBE Insurance • Psychological injuries in workers compensation claims • Colin Purdy, Barrister, Edmund Barton Chambers • Managing claims and approaching dispute resolution in • Gaius Whiffin, Partner, Turner Freeman the current environment: an insurer’s perspective • Liability of principal contractors Melbourne: • His Honour Judge Philip Misso, County Court of • Personal Injury and the regulator Victoria • Assessing damages for catastrophic injury: key • Dorothy Frost, Director-Return to Work Division, considerations and recent trends WorkSafe Victoria • Disease provisions in workers’ claims • Raj Kanhai, Long Tail Claims Manager, QBE Insurance • Identifying the evidence needed to successfully bring • Anne Sheehan, Barrister, Douglas Menzies Chambers medical negligence claims • Jacinta Forbes, Barrister, Owen Dixon Chambers East • Sasha Manova, Barrister, Isaacs Chambers Claim 6 CPD/MCLE points Product of: Early bird discount -

Fact Sheet 2 the FIRST COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT

Fact Sheet 2 THE FIRST COMMONWEALTH PARLIAMENT 1901 FEDERATION AND ’S VOTE THE PEOPLE Overview 1897-1903 Once the Australian Constitution had been accepted by voters in the Australian colonies and enacted as law by British Parliament, the process of putting the new system of federal government into practice began. The Australian colonies were now States of the Commonwealth of Australia, and the office of Governor- General represented the reigning monarch of Britain as Head of the Commonwealth. The first Governor-General of Australia, Lord Hopetoun, proclaimed the Commonwealth of Australia at a special ceremony in Centennial Park, Sydney, 1 January 1901. It was also the Governor-General’s task to commission an interim or caretaker ministry until the Australian people were able to elect their representatives to the newly created Commonwealth Parliament. These interim ministers, with Edmund Barton as Prime Minister, were sworn in as part of the inaugural ceremony at Centennial Park. Over the next 1891 first Constitutional Convention to draft months they organised the first federal election and made a federal constitution arrangements for the opening of the first Commonwealth 1893 Parliament. first ‘people’s convention’ at Corowa 1897 The first federal election delegates elected to a representative Constitutional Convention On Friday 29 March and Saturday 30 (in Queensland and South Australia) voters took part in the first election of 1898-1900 referendums on the Constitution representatives to the Parliament of the Commonwealth of held in all colonies Australia. Because there was as yet no federal electoral law, 1901 the election took place in accordance with the voting 1 January - inauguration of the legislation in each of the States. -

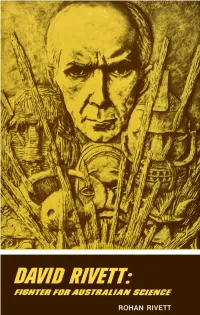

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

John Christian WATSON Prime Minister 27 April to 17 August 1904

3 John Christian WATSON Prime Minister 27 April to 17 August 1904 Chris Watson became the 3rd Prime Minister when the government of Alfred Deakin, a Protectionist, fell due to Labor’s refusal to support the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill. Member of Australian Labor Party 1900-16; Nationalist Party 1917-c1922. Member for Bland (NSW) in House of Representatives 1901-06 and for South Sydney 1906-10. Treasurer 1904. Prior to 1901 he was the Member for Young in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly 1894-1901. Watson was replaced as prime minister by George Reid, of the Free Trade Party, when Labor’s amended Conciliation and Arbitration Bill failed to win support in parliament. Watson resigned after unsuccessfully seeking a double dissolution election. Main achievements (1904) Headed the world’s first national Labor government. The main achievement of Watson’s prime ministership was the advancement of the Conciliation and Arbitration Bill, which was eventually passed in December 1904 under the Reid government. Personal life Born 9 April 1867, Valparaiso, Chile, son of Johan Christian Tanck and his wife Martha. Became Watson when Martha remarried in 1869. Reared in New Zealand. Died 18 November, 1941, Sydney. Limited formal education in New Zealand. Worked as nipper on railway construction at age of ten and on father’s farm. Became a compositor with New Zealand newspapers, active in the union, and migrated to Sydney after losing his job in 1886. Worked as compositor on Sydney newspapers and active in the Typographical Association of New South Wales. Delegate to the NSW Trades and Labor Council 1890. -

Reluctant Lawyer, Reluctant Politician

Alfred Deakin (1856–1919) Australia’s 2nd Prime Minister Terms of office 24 September 1903 to 27 April 1904 • 5 July 1905 to 13 November 1908 • 2 June 1909 to 29 April 1910 Reluctant lawyer, reluctant politician Deakin first met David Syme, the Scottish-born owner of The Age newspaper, in May 1878, as the result of their mutual interest in spiritualism. Soon after, Syme hired the reluctant lawyer on a trial basis, and he made an immediate impression. Despite repeatedly emphasising how ‘laborious’ journalism could be, Deakin was good at it, able to churn out leaders, editorials, investigative articles and reviews as the occasion demanded. Syme wielded enormous clout, able to make and break governments in colonial Victoria and, after 1901, national governments. A staunch advocate of protection for local industry, he ‘connived’ at Deakin’s political education, converting his favourite young journalist, a free-trader, into a protectionist. As Deakin later acknowledged, ‘I crossed the fiscal Rubicon’, providing a first clear indication of his capacity for political pragmatism--his willingness to reshape his beliefs and ‘liberal’ principles if and when the circumstances required it. Radical MLA David Gaunson dismissed him as nothing more than a ‘puppet’, ‘the poodle dog of a newspaper proprietor’. Syme was the catalyst for the start of Deakin’s political career in 1879-80. After two interesting false starts, Deakin was finally elected in July 1880, during the same year that a clairvoyant predicted he would soon embark on a life-changing journey to London to participate in a ‘grand tribunal’. Deakin did not forget what he described as ‘extraordinary information’, and in 1887 he represented Victoria at the Colonial Conference in London.