The Transformation of Cultural Values in Depok Society in West Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indonesian Independence Day Celebration 1

rd Quarterly Bulletin of PT. Citra Abadi Sejati | Busana Apparel Group 3 Quarter 2014 Edition 2 Contents Indonesian Independence Day Celebration 1 InP the Indonesiane language “peduli”DULI means care Employee Welfare & Development 2 A commitment to care for our employees and the environment Environmental & Energy Greetings from the Chairman... Sustainability 3 rd th In the 3 quarter of 2014, we have taken great pride in the 69 year of Indonesia’s Independence. We, Busana Apparel Group, hope to continuously make a meaningful contribution to the country’s continued growth and prosperity. Happy reading and let’s always be “peduli”. Regards, M. Maniwanen Local Community Care 4 Indonesian Independence Day Celebration Sports, Arts, and Cooking Competitions In commemoration of Indonesia's 69th Independence Day on August 17, all units of PT. Citra Abadi Sejati held a festive celebration involving all management and employees. Competitions of sports, arts, and cooking were organized; bringing great joy and deeper unity amidst our employees. Prizes for the participants and winners ranged from stationery to shopping vouchers to housewares to a 32” LCD TV. Tug of war games Cracker eating contest for employees’ children Cooking rice cone competition Dance competition Football match Door-prizes distribution 2Quarterly Bulletin of PT. Citra Abadi Sejati Employee Welfare Development Breaking Fast Together Supplementary Health Care Last July 2014 was the Ramadhan holy month in which all of Winston Churcill once said, “Healthy citizens are the greatest the Muslims around the world fasted for 30 days. Every year, asset any country can have.”For Busana Apparel Group, PT. Citra Abadi Sejati holds an event for employees to break keeping employees healthy is a full time commitment. -

Gouverneur-Generaals Van Nederlands-Indië in Beeld

JIM VAN DER MEER MOHR Gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië in beeld In dit artikel worden de penningen beschreven die de afgelo- pen eeuwen zijn geproduceerd over de gouverneur-generaals van Nederlands-Indië. Maar liefs acht penningen zijn er geslagen over Bij het samenstellen van het overzicht heb ik de nu zo verguisde gouverneur-generaal (GG) voor de volledigheid een lijst gemaakt van alle Jan Pieterszoon Coen. In zijn tijd kreeg hij geen GG’s en daarin aangegeven met wie er penningen erepenning of eremedaille, maar wel zes in de in relatie gebracht kunnen worden. Het zijn vorige eeuw en al in 1893 werd er een penning uiteindelijk 24 van de 67 GG’s (niet meegeteld zijn uitgegeven ter gelegenheid van de onthulling van de luitenant-generaals uit de Engelse tijd), die in het standbeeld in Hoorn. In hetzelfde jaar prijkte hun tijd of ervoor of erna met één of meerdere zijn beeltenis op de keerzijde van een prijspen- penningen zijn geëerd. Bij de samenstelling van ning die is geslagen voor schietwedstrijden in dit overzicht heb ik ervoor gekozen ook pennin- Den Haag. Hoe kan het beeld dat wij van iemand gen op te nemen waarin GG’s worden genoemd, hebben kantelen. Maar tegelijkertijd is het goed zoals overlijdenspenningen van echtgenotes en erbij stil te staan dat er in andere tijden anders penningen die ter gelegenheid van een andere naar personen en functionarissen werd gekeken. functie of gelegenheid dan het GG-schap zijn Ik wil hier geen oordeel uitspreken over het al dan geslagen, zoals die over Dirck Fock. In dit artikel niet juiste perspectief dat iedere tijd op een voor- zal ik aan de hand van het overzicht stilstaan bij val of iemand kan hebben. -

Jakarta-Bogor-Depok-Tangerang- Bekasi): an Urban Ecology Analysis

2nd International Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Civil Engineering (ICEECE'2012) Singapore April 28-29, 2012 Transport Mode Choice by Land Transport Users in Jabodetabek (Jakarta-Bogor-Depok-Tangerang- Bekasi): An Urban Ecology Analysis Sutanto Soehodho, Fitria Rahadiani, Komarudin bus-way, monorail, and Waterway [16]. However, these Abstract—Understanding the transport behaviour can be used to solutions are still relatively less effective to reduce the well understand a transport system. Adapting a behaviour approach, congestion. This is because of the preferences that are more the ecological model, to analyse transport behaviour is important private vehicles- oriented than public transport-oriented. because the ecological factors influence individual behaviour. DKI Additionally, the development of an integrated transportation Jakarta (the main city in Indonesia) which has a complex system in Jakarta is still not adequate to cope with the transportation problem should need the urban ecology analysis. The problem. research will focus on adapting an urban ecology approach to analyse the transport behaviour of people in Jakarta and the areas nearby. The Understanding the transport behaviour can be used to well research aims to empirically evaluate individual, socio-cultural, and understand a transport system. Some research done in the environmental factors, such as age, sex, job, salary/income, developed countries has used the behaviour approach to education level, vehicle ownership, number and structure of family encourage changes in behaviour to be more sustainable such members, marriage status, accessibility, connectivity, and traffic, as the use of public transport, cycling, and walking as a mode which influence individuals’ decision making to choose transport of transportation (to be described in the literature review). -

UMPK KOTA DEPOK English

GOVERNOR OF WEST JAVA DECREE NUMBER: 561/Kep.Kep.681-Yanbangsos/2017 CONCERNING MINIMUM WAGE FOR SPECIFIC LABOR-INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES ON THE INDUSTRY TYPE OF GARMENT IN DEPOK CITY YEAR 2017 THE GOVERNOR OF WEST JAVA Considering : a. whereas District/City Minimum Wage in West Java Province Year 2017 has been set based on Governor of West Java Decree Number 561/Kep.1191-Bangsos/2016; b. whereas in order to maintain business continuity of the industry type of Garment and to avoid termination of employment at Garment Industry enterprises in Depok City, it is necessary to stipulate the Minimum wage for specific labor- intensive industries on the industry type of garment; c. whereas based on the considerations as referred to in letters a and b, it is necessary to stipulate the Governor of West Java Decree concerning the 2017 Minimum wage for specific labor-intensive industries on the industry type of garment in Depok City; In view of : 1. Law Number 11 of 1950 concerning the Establishment of West Java Province (State Gazette of the Republik of Indonesia dated 4 July 1950) jo. Law Number 20 of 1950 concerning The Government of Great Jakarta (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Year 1950 Number 31, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 15) as amended several times, the latest of which by Law Number 29 of 2007 concerning Provincial Government of Jakarta Capital Special Region as the Capital of the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Year 2007 Number 93, Supplement to the State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 4744) and Law Number 23 of 2000 concerning the Establishment of Banten Province (State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Year 2000 Number 182, Supplement to State Gazette of the Republic of Indonesia Number 4010); 2. -

Kesesuaian Penataan Ruang Dan Potensi Investasi Di Kabupaten Bogor

KESESUAIAN PENATAAN RUANG DAN POTENSI INVESTASI DI KABUPATEN BOGOR Frans Dione Institut Pemerintahan Dalam Negeri [email protected] ABSTRACT Bogor Regency is a district that is geographically close to the Capital City, Jakarta. This position and the potential of natural resources makes Bogor District have a great opportunity to develop investment. Investment will come into an area if the spatial policy is made in line and congruent with the potential of the investment development. This is very important for investors, because of it involves support from local government and going concern of the business. The main problem of this research is whether the spatial policy is accordance with the investment potential? This research is a descriptive research using qualitative approach. Empirical exploration is done through desk study and focus group disscusion. In addition, a prospective analysis is conducted which is analyzing strategic issues in investment development that can produce solutions for future decision makers. The results showed that there is suitabilty in spatial policy with the potential of empirical investment of each subregion. The suitability can be seen from 9 (nine) prospective investment sectors in Bogor Regency which are agriculture, fishery, animal husbandry, forestry, mining, tourism, infrastructure, industry and trade. For recommendations, the local government of Bogor Regency have to determine the superior product or commodity for each susbregion and establish priority scale for each investment sector. Keywords: spatial arrangement, potential investment, regional development. PENDAHULUAN Pembangunan suatu wilayah tidak akan lepas dari faktor endowment atau potensi yang dimilikinya. Pesatnya perkembangan Kabupaten Bogor merupakan hasil pemanfaatan potensi yang dimiliki dengan didukung oleh investasi yang ditanamkan baik oleh investor dalam maupun investor luar negeri, serta tidak lepas dari upaya pemerintah daerah dan peran serta dunia usaha yang ada di wilayah Kabupaten Bogor. -

Pola Praktik Kehidupan Komunitas Orang Asli Kukusan Di Depok Jawa Barat Patterns of Life of Kukusan Communities in Depok, West Java

Pola Praktik Kehidupan Orang Asli Kukusan..... (Arie Januar) 171 POLA PRAKTIK KEHIDUPAN KOMUNITAS ORANG ASLI KUKUSAN DI DEPOK JAWA BARAT PATTERNS OF LIFE OF KUKUSAN COMMUNITIES IN DEPOK, WEST JAVA Arie Januar BPNB Jayapura – Papua Jl. Isele Waena Kampung, Waena-Jayapura e-mail: [email protected] Naskah Diterima: 2 Maret 2016 Naskah Direvisi:4 April 2016 Naskah Disetujui:2 Mei 2016 Abstrak Tulisan ini mendiskusikan tentang pola ‘orang asli’ menghadapi transformasi sosial ekonomi. Transformasi yang terjadi begitu cepat mengakibatkan perubahan struktur pada komponen ‘orang asli’. Oleh karena itu, untuk mengurangi dampak dari kemajuan tersebut, mereka membentuk suatu organisasi sosial dalam komunitasnya, sebagai bentuk upaya mempertahankan diri. Organisasi sosial akar rumput yang terbentuk dalam sebuah ikatan kolektif, yakni kekerabatan, spasial, dan keagamaan, masing-masing melahirkan modal sosial dalam menghadapi pembangunan. Apabila ikatan sosial mereka kuat, ‘orang asli’ cenderung lebih mudah beradaptasi dengan dunia baru di lingkungannya, terutama dalam aspek sosial ekonomi, dan budaya. Tulisan ini menggunakan pendekatan kualitatif, dengan tujuan agar dapat menyelami lebih dalam pola adaptasi ‘orang asli’ di tengah transformasi sosial ekonomi. Pola pikir ini bertumpu pada ikatan kolektivitas mereka dalam organisasi sosial akar rumput, yang mana dengan kegiatan tersebut melahirkan peluang-peluang sosial ekonomi yang menjadi pijakan untuk melestarikan komunitas mereka di Kukusan Depok. Kata kunci: adaptasi, sosial, ekonomi,komunitas, kukusan. Abstract This paper discusses the pattern of 'indigenous people' facing socio-economic transformation. Transformation happens so quickly lead to structural changes in the components 'indigenous people'. So as to reduce the impact of such advances, they form a grass-roots organization in the community, as a form of self-defense. -

Mapping of Travel Activity Pattern to the Cbd in The

MAPPING OF TRAVEL ACTIVITY PATTERN TO THE CBD IN THE DEPOK AREA Sugeng Rahardjo & Cholifah Bahaudin Department of Geography Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences University of Indonesia Tel/Fax : 62-21-7270030 E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Mapping of travel activity pattern to the CBD is more important as an information to the decision makers to plan the city. This information included the location of place which is obviously needed when the traveller is trying to find a given destination and also on the attributes or characteristics of a place. Those information is required if the individual tries to assess the likelihood that a destination will satisfy a given need. Development of the new CBD, will change the previous land use to become paved area. Meanwhile, the Depok city was considered to be the catchment area. To avoid mismanagement in urban environment, the development of new public facilities should pay attention to the carrying capacity of the area. Depok was rural area before the government developed large settlement for the civil servants in 1976, and after that it became a bedroom community. The development influenced the residents commuting activities to travel out of Depok area to work, school, shopping and so on. In 1987, the University of Indonesia was moved from Jakarta to Depok. Population growth in the Depok area between 1990-1998 was decreased from 12.26 percent to 7.8 percent, however, it was still very high compared to the Jakarta Metropolitan area (2.6 percent). Meanwhile, the land use settlement was increased from 46 percent to 72.22 percent of the total area of Depok. -

Women Entrepreneurs In

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized THE WORLD BANK OFFICE JAKARTA Indonesia Stock Exchange Building, Tower 2, 12th floor .Jl. Jend. Sudirman Kav. 52-53 Jakarta 12910 Tel: (6221) 5299-3000 Fax: (6221) 5299-3111 Published April 2016 Women Entrepreneurs in Indonesia: A Pathway to Increasing Shared Prosperity was produced by staff of the World Bank with financial support provided by the Swiss Government. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denomination and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement of acceptance of such boundaries. All photos are Copyright ©World Bank Indonesia Collection. All rights reserved. For further questions about this report, please contact I Gede Putra Arsana ([email protected]), Salman Alibhai ([email protected]). WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS IN INDONESIA A Pathway to Increasing Shared Prosperity April, 2016 Finance and Markets Global Practice East Asia Pacific Region WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS IN INDONESIA: A PATHWAY TO INCREASING SHARED PROSPERITY Foreword The world today believes that supporting women entrepreneurs is vital for economic growth. As economic opportunities increase, unprecedented numbers of women are entering the world of business and entrepreneurship. The number of women entrepreneurs has risen in global economy including in developing countries. -

Compilation of Manuals, Guidelines, and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (Ip) Portfolio Management

DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION COMPILATION OF MANUALS, GUIDELINES, AND DIRECTORIES IN THE AREA OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY (IP) PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT CUSTOMIZED FOR THE ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN NATIONS (ASEAN) MEMBER COUNTRIES TABLE OF CONTENTS page 1. Preface…………………………………………………………………. 4 2. Mission Report of Mr. Lee Yuke Chin, Regional Consultant………… 5 3. Overview of ASEAN Companies interviewed in the Study……...…… 22 4. ASEAN COUNTRIES 4. 1. Brunei Darussalam Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 39 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 53 4. 2. Cambodia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 66 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 85 4. 3. Indonesia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 96 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 113 4. 4. Lao PDR Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 127 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 144 4. 5. Malaysia Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 156 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 191 4. 6. Myanmar Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 213 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 232 4. 7. Philippines Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. 248 Part II: Success Stories…………………………………………………. 267 4. 8. Singapore Part I: Listing of Manuals, Guidelines and Directories in the Area of Intellectual Property (IP) Portfolio Management………………………. -

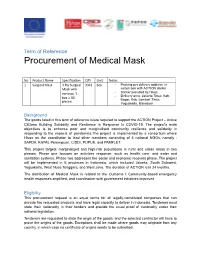

Term of Reference Procurement of Medical Mask

Term of Reference Procurement of Medical Mask No Product Name Specificaon QTY Unit Notes 1 Surgical Mask 3 Ply Surgical 3341 box - Packing per delivery address in Mask with carton box with ACTION sticker earloop; 1 - Sticker provided by Hivos - Delivery area: Jakarta Timur, Kab. box = 50 Bogor, Kab. Lombok Timur, pieces Yogyakarta, Makassar Background The goods listed in this term of reference is/are required to support the ACTION Project – Active Citizens Building Solidarity and Resilience in Response to COVID-19. The project’s main objectives is to enhance poor and marginalised community resilience and solidarity in responding to the impacts of pandemics.The project is implemented by a consortium where Hivos as the coordinator to lead other members consisting of 5 national NGOs, namely : SAPDA, KAPAL Perempuan, CISDI, PUPUK, and PAMFLET. This project targets marginalized and high-risk populations in rural and urban areas in two phases. Phase one focuses on activities response, such as health care, and water and sanitation systems. Phase two addresses the social and economic recovery phase. The project will be implemented in 5 provinces in Indonesia, which included Jakarta, South Sulawesi, Yogyakarta, West Nusa Tenggara, and West Java. The duration of ACTION is in 24 months. The distribution of Medical Mask is related to the Outcome I: Community-based emergency health responses amplified, and coordination with government initiatives improved Eligibility This procurement request is on equal terms for all legally-constituted companies that can provide the requested products and have legal capacity to deliver in Indonesia. Tenderers must state their nationality in their tenders and provide the usual proof of nationality under their national legislation. -

Jan Van Riebeeck, De Stichter Van GODEE MOLSBERGEN Hollands Zuid-Afrika

Vaderlandsche cuituurgeschiedenis PATRIA in monografieen onder redactie van Dr. J. H. Kernkamp Er is nagenoeg geen Nederlander, die niet op een of andere wijze door zijn levensonderhoud verbonden is met ons koloniaal rijk overzee, en die niet belang- stelling zou hebben voor de mannen, die dit rijk hielpen stichten. Dr. E. C. Een deter is Jan van Riebeeck, de Stichter van GODEE MOLSBERGEN Hollands Zuid-Afrika. Het zeventiende-eeuwse avontuurlijke leven ter zee en te land, onder Javanen, Japanners, Chinezen, Tonkinners, Hotten- Jan van Riebeeck totten, de koloniale tijdgenoten, hun voortreffelijke daden vol moed en doorzicht, hun woelen en trappen en zijn tijd oxn eer en geld, het zeemans lief en leed, dat alles Een stuk zeventiende-eeuws Oost-Indie maakte hij mee. Zijn volharding in het tot stand brengen van wat van grote waarde voor ons yolk is, is spannend om te volgen. De zeventiende-eeuwer en onze koloniale gewesten komen door dit boek ons nader door de avonturen. van de man, die blijft voortleven eeuwen na zijn dood in zijn Stichting. P. N. VAN KAMPEN & LOON N.V. AMSTERDAM MCMXXXVII PAT M A JAN VAN RIEBEECK EN ZIJN TIJD PATRIA VADERLANDSCHE CULTUURGESCHIEDENIS IN MONOGRAFIEEN ONDER REDACTIE VAN Dr. J. H. KERNKAMP III Dr. E. C. GODEE MOLSBERGEN JAN VAN RIEBEECK EN ZIJN TIJD Een stuk zeventiende-eeuws Oost-Indie 1937 AMSTERDAM P. N. VAN KAMPEN & ZOON N.V. INHOUD I. Jeugd en Opvoeding. Reis naar Indio • • . 7 II. Atjeh 14 III. In Japan en Tai Wan (= Formosa) .. .. 21 IV. In Tonkin 28 V. De Thuisreis 41 VI. Huwelijk en Zeereizen 48 VII. -

Public Expose PT Metropolitan Land Tbk Jakarta, 18 September 2019 AGENDA

Public Expose PT Metropolitan Land Tbk Jakarta, 18 September 2019 AGENDA Profil Perseroan 3 Kinerja Keuangan 10 Portofolio Proyek 15 Proyek yang sedang berjalan: perumahan 17 Proyek yang sedang berjalan: komersial 22 Proyek dalam pengembangan dan perencanaan 27 Penghargaan, CSR dan lain-lain 32 2 PROFIL PERSEROAN 3 TENTANG METLAND • PT Metropolitan Land Tbk didirikan pada tanggal 16 Februari 1994 yang merupakan bagian dari Grup Metropolitan. • Menjadi perusahaan publik dengan ticker code MTLA pada Juni 2011. • Perusahaan pengembang properti yang berfokus kepada kelas menengah. • Memiliki 7 proyek perumahan di lokasi yang tersebar di Jabodetabek dan 9 proyek komersial yang mencakup pusat perbelanjaan, hotel berbintang, gedung perkantoran dan apartemen 4 STRUKTUR PEMEGANG SAHAM PT Metropolitan Persada Reco Newton Pte Ltd Publik International 37,50 % 25,8 % 36,70 % PT Metropolitan Land Tbk 5 Per 30 Juni 2019 STRUKTUR PERSEROAN PT Metropolitan Land Tbk . Metland Menteng PT Metropolitan Global Management PT Metropolitan Permata Development . JO Project with Keppel . Metland Cileungsi . Metland Puri . Metropolitan Mall Bekasi . Hotel Management License . The Riviera at Puri . Hotel Horison Ultima Bekasi . Metland Tambun . M-Gold Tower . @HOM Hotel & Plaza Metropolitan Tambun . Grand Metropolitan PT Kembang Griya Cahaya . Metland Transyogi PT Agus Nusa Penida PT Metropolitan Graha Management . Kaliana Apartment . Metropolitan Mall Cileungsi . Hotel Horison Ultima Seminyak Hotel Operator . Royal Venya Ubud, Bali PT Metropolitan Lampung Graha PT Sumber Sentosa Guna Lestari . Metland Hotel Lampung PT Metropolitan Karyadeka . Graha Metland Cawang Development PT Metropolitan Manajemen (50,01%) . Metland Cyber City Building Management PT Fajarputera Dinasti PT Metropolitan Deta Graha (60%) . Metland Cibitung PT Metropolitan Karyadeka Ascendas . Metland Hotel Cirebon Catatan: anak perusahaan dimiliki (50,01%) PT Sumber Tata Lestari PT Metropolitan Kertajati sebesar 99% kecuali untuk yang .