Volume 30 2003 Issue 98

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Conversation Living Feminist Politics - Amina Mama Interviews Winnie Byanyima

Conversation Living Feminist Politics - Amina Mama interviews Winnie Byanyima Winnie Byanyima is MP for Mbarara Municipality in Western Uganda. The daughter of two well-known politicians, she was a gifted scholar and won awards to pursue graduate studies in aeronautical engineering. However, she chose to join the National Resistance Movement under Museveni's leadership, and later became one of the first women to stand successfully for direct elections. Winnie is best known for her gender advocacy work with non- governmental organisations, her anti-corruption campaigns, and her opposition to Uganda's involvement in the conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. She is currently affiliated to the African Gender Institute, where she is writing a memoir of three generations of women – her grandmother, her mother and her own life in politics. Here she is interviewed by Amina Mama on behalf of Feminist Africa. Amina Mama: Let's begin by talking about your early life, and some of the formative influences. Winnie Byanyima: I grew up pretty much my father's daughter. I admired him very much, and people said I was like him. I had a more difficult relationship with my mother. But in the last few years as I've tried to reflect on who I am and why I believe the things that I believe, I've found myself coming back to my mother and my grandmother, and having to face the fact that I take a lot from those women. It's tough, because it means that I must recognise all that I didn't take as important about my mother's struggles. -

Uganda Assessment October 2002

UGANDA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2002 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda October 2002 CONTENTS 1 Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.4 2 Geography 2.1 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 1989 Elections 4.2 - 4.3 5 State Structures 5.1 - 5.6 The Constitution 5.7 - 5.8 Citizenship & Nationality 5.9 - 5.28 Political System 5.29 - 5.33 Judiciary 5.34 Treason 5.35 Legal Rights & Detention 5.36 - 5.38 Death Penalty 5.39 - 5.49 Internal Security 5.50 - 5.57 Security Forces 5.58 - 5.63 Prisons & Prison Conditions 5.64 - 5.65 Military Service 5.66 - 5.70 Medical Services 5.71 Disabilities 5.72 - 5.75 Educational System 6 Human Rights 6A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.7 Human Rights Monitoring 6.8 - 6.9 Uganda Human Rights Commission 6.10 Insurgency 6.11 - 6.14 Amnesties 6.15 - 6.19 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.20 - 6.25 Freedom of Religion 6.26 - 6.29 Freedom of Assembly & Association 6.30 - 6.32 Employment Rights 6.33 - 6.36 People Trafficking 6.37 Freedom of Movement 6.38 - 6.39 Internal Flight 6.40 Refugees 6.41 - 6.42 6B Human Rights - Specific Groups Ethnic Groups Acholi 6.43 - 6.46 Karamojong 6.47 - 6.56 Uganda October 2002 Women 6.57 - 6.60 Children 6.61 - 6.64 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 6.65 - 6.73 Homosexuals 6.74 - 6.75 Religious Groups 6.76 Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God Rebel Groups 6.77 - 6.82 Lords Resistance Army (LRA) 6.83 - 6.86 Aims of the LRA 6.87 - 6.96 Latest LRA Attacks 6.97 - 6.105 UPDF reception of the LRA 6.106 - 6.108 Allied -

KAS Democracy Report 2009

62 KAS Democracy Report 2009 uganda Sallie Simba Kayunga i. generaL information Political system uganda has a presidential system. The president and members of the ugandan Parliament (mPs) are elected separately. While the president and parliament each have different constitutional responsibilities, some of their responsibilities are interdependent. The president is both head of state and government and performs both the titular and executive functions. The president appoints ministers, ambassadors, the inspector general of the government and the inspector general of police. furthermore, he or she appoints, on the advice of the Judicial Service Commission, the chief justice, his or her deputy, the principle judge, judges of the Supreme Court, judges of the Court of Appeal and the panel of judges of the High Court. Whereas such presidential appointments are subject to parliamentary approval, there have been only rare instances when parliament has rejected a presidential appointee. As in other presidential systems, the president has, for example, the prerogative to declare war and also has the prerogative of mercy. The constitution also provides for the position of a prime minister, who is the leader of government business in parliament and who also coordinates the implementation of government policies, but without any executive powers. The prime minister is appointed by, and is accountable to, the president. Some of the common characteristics of a parliamentary system can also be identified in the ugandan political system. most of the ministers are, for example, appointed from among mPs to the extent that out of the 332 mPs, 69 or 21 per cent are active ministers. -

Political Theologies in Late Colonial Buganda

POLITICAL THEOLOGIES IN LATE COLONIAL BUGANDA Jonathon L. Earle Selwyn College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It does not exceed the limit of 80,000 words set by the Degree Committee of the Faculty of History. i Abstract This thesis is an intellectual history of political debate in colonial Buganda. It is a history of how competing actors engaged differently in polemical space informed by conflicting histories, varying religious allegiances and dissimilar texts. Methodologically, biography is used to explore three interdependent stories. First, it is employed to explore local variance within Buganda’s shifting discursive landscape throughout the longue durée. Second, it is used to investigate the ways that disparate actors and their respective communities used sacred text, theology and religious experience differently to reshape local discourse and to re-imagine Buganda on the eve of independence. Finally, by incorporating recent developments in the field of global intellectual history, biography is used to reconceptualise Buganda’s late colonial past globally. Due to its immense source base, Buganda provides an excellent case study for writing intellectual biography. From the late nineteenth century, Buganda’s increasingly literate population generated an extensive corpus of clan and kingdom histories, political treatises, religious writings and personal memoirs. As Buganda’s monarchy was renegotiated throughout decolonisation, her activists—working from different angles— engaged in heated debate and protest. -

Copyright © Anthony C.K. Kakooza, 2014 All Rights Reserved

Copyright © Anthony C.K. Kakooza, 2014 All rights reserved THE CULTURAL DIVIDE: TRADITIONAL CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS AND THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES BY ANTHONY C.K. KAKOOZA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of the Science of Law in Law in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jay Kesan, Chair Professor Bob Lawless Professor Anna-Marie Marshall Professor Thomas Ulen ABSTRACT This study addresses a number of pertinent issues concerning Traditional Cultural Expressions [TCEs], specifically in relation to what they are and the dilemma surrounding ownership vis-à-vis custodianship in an environment that is biased towards protection of Intellectual Property Rights. The present inadequate legal recognition and, ultimately, insufficient international recognition and protection of TCEs has orchestrated the misappropriation of such works for the benefit of the entertainment industry and other economic sectors as well. The biggest underlying issue therefore is – whether TCEs should be recognized within the domain of Intellectual Property Rights. The fact that TCEs are considered as part of the public domain raises a key issues as to how they can be protected so as to serve the interests of ethnic communities, States, as well as the users of the TCEs. The claim made in this study is that because of the communal nature of ownership and difficulty in defining TCEs, this has contributed to their abuse by all users. The current origin-based I.P regimes are considered as inadequate in protecting TCEs which are mainly characterized by communal ownership and absence of fixation. -

Press Review September 2016, Edition 15

PRESS REVIEW John Paul II Justice and Peace Centre “Faith Doing Justice” EDITION 15 SEPTEMBER 2016 THEMATIC AREAS Plot 2468 Nsereko Road-Nsambya Education P.O. Box 31853, Kampala-Uganda Environment Tel: +256414267372 Health Mobile: 0783673588 Economy Email: [email protected] Religion and Society [email protected] Politics Website: www.jp2jpc.org Youth Christian Reflection EDUCATION MPs decry varsity staff shortage. Lawmakers on parliament’s Education Committee have asked government to increase funding to public universities so that they can fill the vacant positions, particularly the teaching staff, which are needed to lift the quality of education in the country. Dokolo north MP Paul Amoru said the low staffing level at MUST (Mbarara University of Science and Technology) is a serious concern because it was set up to be developed as governments major science institution. Govt nursery schools to start next year. Plans are underway by the Education Ministry to introduce nursery classes in its public primary schools across the country in the next academic year. Rosemary Seninde, State Minister for primary education, emphasised that the education ministry would now put much emphasis on the children’s early childhood education which is nursery education. Teachers reject govt transfer plan. A number of the head teachers joined the Anglican Bishop of Ankole diocese in rejecting a looming policy which bars teachers who are married from working at the same station. Ms Nakatte Kikomeko, the head teacher of Nabbingo girl’s school, however, said administrative issues could arise in case the man is a director of studies and his wife is teaching in the school. -

2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003

Uganda Page 1 of 26 Uganda Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003 President Yoweri Museveni continued to dominate the Government after he was reelected to a second 5-year term in March 2001. He has ruled since 1986 through the dominant political party, The Movement. The Constitution provides for an autonomous, independently elected President and a 295-member unicameral Parliament whose members were elected to 5-year terms. The Parliament was weak compared to the Executive, although it occasionally displayed independence and assertiveness. In the June 2001 parliamentary elections, more than 50 percent of those elected were new legislators; however, Movement supporters remained in control of the legislative branch. Observers believed that the 2001 presidential and parliamentary elections generally reflected the will of the population; however, both were marred by serious irregularities, particularly in the period leading up to the elections, such as restrictions on political party activities, incidents of violence, voter intimidation, and fraud. A 2000 national referendum on the role of political parties formally extended the Movement form of government indefinitely and severely restricted political activities. The Constitutional Review Commission (CRC) continued to work to amend the 1995 Constitution during the year. The judiciary generally was independent but was understaffed and weak; the President had extensive legal powers. The Uganda People's Defense Force (UPDF) was the key security force. The Constitution provides for civilian control of the UPDF, with the President designated as Commander in Chief; a civilian served as Minister of Defense. -

The Cotter Pin by Andrew Rice

AR-7 Sub-Saharan Africa Andrew Rice is a Fellow of the Institute studying life, politics and development in ICWA Uganda and environs. LETTERS The Cotter Pin By Andrew Rice JANUARY 1, 2003 Since 1925 the Institute of KAMPALA, Uganda—The sirens’ wail was getting louder. Outside the Nile Current World Affairs (the Crane- Hotel’s International Conference Center, the hexagonal slab of port-holed con- Rogers Foundation) has provided crete where three decades of Ugandan presidents have welcomed important visi- long-term fellowships to enable tors, the blue-uniformed honor guard stiffened to attention in the late-November outstanding young professionals heat. The ministers and generals took their places on the steps. Reporters pulled to live outside the United States out their notebooks, news photographers lifted their cameras to their shoulders. and write about international All eyes fixed on the front gates. The presidents were about to arrive. areas and issues. An exempt operating foundation endowed by A little after 10a.m., a pickup truck peeled through the gates, loaded with the late Charles R. Crane, the security officers, machine guns at the ready. A pair of motorcycle police followed, Institute is also supported by leading the way for the black Mercedes limousine. It glided to the front of the contributions from like-minded building and stopped. individuals and foundations. The doors of the limousine opened, and the presidents emerged. From one side, His Excellency Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, president of Kenya, dressed in his customary fashion: a dark blue suit and a garish multicolored necktie. From TRUSTEES the other, His Excellency Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, president of Uganda, nattily Bryn Barnard attired as always. -

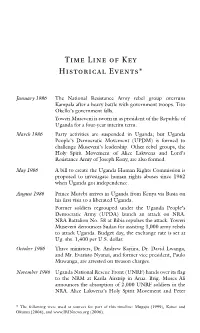

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006).