KAS Democracy Report 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country

UGANDA COUNTRY REPORT October 2004 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda Report - October 2004 CONTENTS 1. Scope of the Document 1.1 - 1.10 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.2 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.3 4. History 4.1 – 4.2 • Elections 1989 4.3 • Elections 1996 4.4 • Elections 2001 4.5 5. State Structures Constitution 5.1 – 5.13 • Citizenship and Nationality 5.14 – 5.15 Political System 5.16– 5.42 • Next Elections 5.43 – 5.45 • Reform Agenda 5.46 – 5.50 Judiciary 5.55 • Treason 5.56 – 5.58 Legal Rights/Detention 5.59 – 5.61 • Death Penalty 5.62 – 5.65 • Torture 5.66 – 5.75 Internal Security 5.76 – 5.78 • Security Forces 5.79 – 5.81 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.82 – 5.87 Military Service 5.88 – 5.90 • LRA Rebels Join the Military 5.91 – 5.101 Medical Services 5.102 – 5.106 • HIV/AIDS 5.107 – 5.113 • Mental Illness 5.114 – 5.115 • People with Disabilities 5.116 – 5.118 5.119 – 5.121 Educational System 6. Human Rights 6.A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.08 • Amnesties 6.09 – 6.14 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.15 – 6.20 • Journalists 6.21 – 6.24 Uganda Report - October 2004 Freedom of Religion 6.25 – 6.26 • Religious Groups 6.27 – 6.32 Freedom of Assembly and Association 6.33 – 6.34 Employment Rights 6.35 – 6.40 People Trafficking 6.41 – 6.42 Freedom of Movement 6.43 – 6.48 6.B Human Rights Specific Groups Ethnic Groups 6.49 – 6.53 • Acholi 6.54 – 6.57 • Karamojong 6.58 – 6.61 Women 6.62 – 6.66 Children 6.67 – 6.77 • Child care Arrangements 6.78 • Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) -

Re Joinder Submitted by the Republic of Uganda

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING ARMED ACTIVITIES ON THE TERRITORY OF THE CONGO DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO v. UGANDA REJOINDER SUBMITTED BY THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA VOLUME 1 6 DECEMBER 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 : THE PERSISTENT ANOMALIES IN THE REPLY CONCERNING MATTERS OF PROCEDURE AND EVIDENCE ............................................... 10 A. The Continuing Confusion Relating To Liability (Merits) And Quantum (Compensation) ...................... 10 B. Uganda Reaffirms Her Position That The Court Lacks Coinpetence To Deal With The Events In Kisangani In June 2000 ................................................ 1 1 C. The Courl:'~Finding On The Third Counter-Claim ..... 13 D. The Alleged Admissions By Uganda ........................... 15 E. The Appropriate Standard Of Proof ............................. 15 CHAPTER II: REAFFIRMATION OF UGANDA'S NECESSITY TO ACT IN SELF- DEFENCE ................................................. 2 1 A. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By The ADF ........................ 27 B. The DRC's Admissions Regarding The Threat To Uganda's Security Posed By Sudan ............................. 35 C. The DRC's Admissions Regarding Her Consent To The Presetnce Of Ugandan Troops In Congolese Territory To Address The Threats To Uganda's Security.. ......................................................................4 1 D. The DRC's Failure To Establish That Uganda Intervened -

NIMD Fostering Multiparty Democracy in Uganda

NIMD fostering multiparty democracy in Uganda The Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy (NIMD) works to promote peaceful, justice and inclusive politics worldwide. Today, as the organisation is celebrating 10 years of operations in Uganda, Daily Monitor’s Paul Murungi, spoke to Mr Frank Rusa, the Country Representative who also doubles as the Executive Secretary of Inter- Party Organisation for Dialogue (IPOD) Council. Below are the excerpts: political platform. We have therefore, for the last shape the agenda and give technical support. I build dialogue, you have to continue building trust 10 years, focused on working with political parties provide support to the secretariat to ensure that I by showing concern over the issues raised. I need to build internal organisational mechanisms for oversee that staff is responding well to programme to tell you that the current chairman of the IPOD conflict resolution, strong accounting systems, objectives and outcomes that we seek to achieve Summit, Mr Asuman Basalirwa has been going robust women and youth leagues, and the way in Uganda. around political parties calling for another summit, political parties should function. and he has informed me that the FDC president, Uganda’s multiparty political landscape has Mr Patrick Oboi Amuriat has expressed willingness Tell us more about the composition of Inter- grown exponentially since 2005 to include many to attend the next summit, so I believe with time, Party Organisation for Dialogue (IPOD). political parties. Why is it that some political we will build trust and parties’ commitment shall In 2009 IPOD was formed on a Memorandum of parties are not part of IPOD? increase. -

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Uganda Assessment October 2002

UGANDA COUNTRY ASSESSMENT October 2002 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Uganda October 2002 CONTENTS 1 Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.4 2 Geography 2.1 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 1989 Elections 4.2 - 4.3 5 State Structures 5.1 - 5.6 The Constitution 5.7 - 5.8 Citizenship & Nationality 5.9 - 5.28 Political System 5.29 - 5.33 Judiciary 5.34 Treason 5.35 Legal Rights & Detention 5.36 - 5.38 Death Penalty 5.39 - 5.49 Internal Security 5.50 - 5.57 Security Forces 5.58 - 5.63 Prisons & Prison Conditions 5.64 - 5.65 Military Service 5.66 - 5.70 Medical Services 5.71 Disabilities 5.72 - 5.75 Educational System 6 Human Rights 6A Human Rights Issues Overview 6.1 - 6.7 Human Rights Monitoring 6.8 - 6.9 Uganda Human Rights Commission 6.10 Insurgency 6.11 - 6.14 Amnesties 6.15 - 6.19 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.20 - 6.25 Freedom of Religion 6.26 - 6.29 Freedom of Assembly & Association 6.30 - 6.32 Employment Rights 6.33 - 6.36 People Trafficking 6.37 Freedom of Movement 6.38 - 6.39 Internal Flight 6.40 Refugees 6.41 - 6.42 6B Human Rights - Specific Groups Ethnic Groups Acholi 6.43 - 6.46 Karamojong 6.47 - 6.56 Uganda October 2002 Women 6.57 - 6.60 Children 6.61 - 6.64 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 6.65 - 6.73 Homosexuals 6.74 - 6.75 Religious Groups 6.76 Movement for the Restoration of the Ten Commandments of God Rebel Groups 6.77 - 6.82 Lords Resistance Army (LRA) 6.83 - 6.86 Aims of the LRA 6.87 - 6.96 Latest LRA Attacks 6.97 - 6.105 UPDF reception of the LRA 6.106 - 6.108 Allied -

List of Abbreviations

HRNJ - Uganda Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) Press Freedom Index Report April 2011 2 HRNJ - Uganda Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Background .............................................................................................. 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 Elections and Media .............................................................................................. 7 Research Objective ............................................................................................... 8 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 8 Quality check ......................................................................................................... 8 Limitations ............................................................................................................. 9 Part II: Media freedom during national elections in Uganda ................................ 11 Media as a campaign tool ................................................................................... 11 Role of regulatory bodies ................................................................................... 12 Media self censorship ......................................................................................... 14 Censorship of social media -

Uganda Program Summary Political Party Strengthening Disabilities

Uganda Program Summary Uganda’s return to multiparty politics following a 2005 referendum created new opportunities for political participation and competition. Nineteen years of de facto one-party rule however, created significant obstacles to peaceful political competition and the establishment of effective, representative political institutions. To support the people of Uganda as they establish a functioning, multiparty democracy in the face of these challenges, the International Republican Institute (IRI) designed a program to strengthen political pluralism, increase the involvement of women, youth, and persons with disabilities in political processes, and to support the development of political parties and organizations. Political Party Strengthening IRI works with political parties to develop strategic plans and to strengthen party structures. Party activities supported by IRI include promoting internal party democracy, increasing communication between party organs and improving internal party organization, so that vital party functions are carried out and established between elections. At the district level, parties have opened offices, recruited volunteers to staff their offices and increased publicity activities. Additionally, the Institute has sponsored an information and communications technology project for parties to establish interactive web forums at www.parties.ug and communicate with their members via SMS technology, the internet and radio. IRI also supports the policy development process of political parties through its work with the parties and their affiliated foundations. For these programs, IRI partners with the four largest parties in Uganda’s parliament: the National Resistance Movement, the Forum for Democratic Change, the Uganda People’s Congress and the Democratic Party. The Institute has also provided limited assistance to two other parties represented in the legislature: the Justice Forum and the Conservative Party. -

UGANDA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

UGANDA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 20 April 2011 UGANDA DATE Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN UGANDA FROM 3 FEBRUARY TO 20 APRIL 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON UGANDA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 3 FEBRUARY AND 20 APRIL 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Political developments: 1962 – early 2011 ......................................................... 3.01 Conflict with Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): 1986 to 2010.............................. 3.07 Amnesty for rebels (Including LRA combatants) .............................................. 3.09 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Kampala bombings July 2010 ............................................................................. 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION.......................................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM .................................................................................................. -

Copyright © Anthony C.K. Kakooza, 2014 All Rights Reserved

Copyright © Anthony C.K. Kakooza, 2014 All rights reserved THE CULTURAL DIVIDE: TRADITIONAL CULTURAL EXPRESSIONS AND THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY IN DEVELOPING ECONOMIES BY ANTHONY C.K. KAKOOZA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of the Science of Law in Law in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Jay Kesan, Chair Professor Bob Lawless Professor Anna-Marie Marshall Professor Thomas Ulen ABSTRACT This study addresses a number of pertinent issues concerning Traditional Cultural Expressions [TCEs], specifically in relation to what they are and the dilemma surrounding ownership vis-à-vis custodianship in an environment that is biased towards protection of Intellectual Property Rights. The present inadequate legal recognition and, ultimately, insufficient international recognition and protection of TCEs has orchestrated the misappropriation of such works for the benefit of the entertainment industry and other economic sectors as well. The biggest underlying issue therefore is – whether TCEs should be recognized within the domain of Intellectual Property Rights. The fact that TCEs are considered as part of the public domain raises a key issues as to how they can be protected so as to serve the interests of ethnic communities, States, as well as the users of the TCEs. The claim made in this study is that because of the communal nature of ownership and difficulty in defining TCEs, this has contributed to their abuse by all users. The current origin-based I.P regimes are considered as inadequate in protecting TCEs which are mainly characterized by communal ownership and absence of fixation. -

2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003

Uganda Page 1 of 26 Uganda Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003 President Yoweri Museveni continued to dominate the Government after he was reelected to a second 5-year term in March 2001. He has ruled since 1986 through the dominant political party, The Movement. The Constitution provides for an autonomous, independently elected President and a 295-member unicameral Parliament whose members were elected to 5-year terms. The Parliament was weak compared to the Executive, although it occasionally displayed independence and assertiveness. In the June 2001 parliamentary elections, more than 50 percent of those elected were new legislators; however, Movement supporters remained in control of the legislative branch. Observers believed that the 2001 presidential and parliamentary elections generally reflected the will of the population; however, both were marred by serious irregularities, particularly in the period leading up to the elections, such as restrictions on political party activities, incidents of violence, voter intimidation, and fraud. A 2000 national referendum on the role of political parties formally extended the Movement form of government indefinitely and severely restricted political activities. The Constitutional Review Commission (CRC) continued to work to amend the 1995 Constitution during the year. The judiciary generally was independent but was understaffed and weak; the President had extensive legal powers. The Uganda People's Defense Force (UPDF) was the key security force. The Constitution provides for civilian control of the UPDF, with the President designated as Commander in Chief; a civilian served as Minister of Defense. -

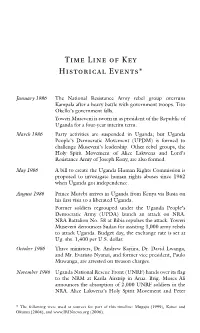

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

IST-Africa 2009 Advance Programme

Conference & Exhibition IST-Africa 2009 Advance Programme Uganda, 6 - 8 May 2009 IST-Africa is supported by the European Commission under the ICT Programme Host Government Major Sponsors Technical Co-Sponsor MINISTRY OF ICT REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Introduction IST-Africa 2009 Conference & Exhibition takes place 06 - 08 May 2009 in Kampala, Uganda. Part of the IST-Africa Initiative, which is supported by the European Commission under the ICT Theme of Framework Programme 7 (FP7), IST-Africa 2009 is the fourth in an Annual Conference Series bringing together delegates from leading commercial, government & research organisations, to bridge the Digital Divide by sharing knowledge, experience, lessons learnt & good practice. European research activities are structured around consecutive multi-annual programmes, or so-called Framework Programmes. FP7 sets out the priorities - including the ICT Priority - for the period 2007 - 2013. ICT is fully open to international co-operation with the aim to join forces for addressing major challenges where significant added value is expected to be gained from a world-wide R&D cooperation. In this context, the European Commission co-funded the IST-Africa Initiative in order to promote the participation of African organisations to the ICT programme. Hosted by the Government of Uganda through the Ministry of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) and Technically Co-Sponsored by IEEE, IST-Africa 2009 focuses on the Role of ICT for Africa's Development and specifically on Applied ICT research in the areas of eHealth, Technology Enhanced Learning and ICT Skills, Open Source Software, ICT for Inclusion, eInfrastructures, ICT for Environmental Risk Management, ICT for Networked Enterprise and eGovernment and eDemocracy.