Patrick E. Mcgovern CHAPTER 3 ANCIENT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fermented Beverages of Pre- and Proto-Historic China

Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China Patrick E. McGovern*†, Juzhong Zhang‡, Jigen Tang§, Zhiqing Zhang¶, Gretchen R. Hall*, Robert A. Moreauʈ, Alberto Nun˜ ezʈ, Eric D. Butrym**, Michael P. Richards††, Chen-shan Wang*, Guangsheng Cheng‡‡, Zhijun Zhao§, and Changsui Wang‡ *Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA), University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA 19104; ‡Department of Scientific History and Archaeometry, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, China; §Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing 100710, China; ¶Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of Henan Province, Zhengzhou 450000, China; ʈEastern Regional Research Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wyndmoor, PA 19038; **Firmenich Corporation, Princeton, NJ 08543; ††Department of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; and ‡‡Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 10080, China Communicated by Ofer Bar-Yosef, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, November 16, 2004 (received for review September 30, 2003) Chemical analyses of ancient organics absorbed into pottery jars A much earlier history for fermented beverages in China has long from the early Neolithic village of Jiahu in Henan province in China been hypothesized based on the similar shapes and styles of have revealed that a mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey, and Neolithic pottery vessels to the magnificent Shang Dynasty bronze fruit (hawthorn fruit and͞or grape) was being produced as early as vessels (8), which were used to present, store, serve, drink, and the seventh millennium before Christ (B.C.). This prehistoric drink ritually present fermented beverages during that period. -

Rosszindulatú Daganatok És Szív– Érrendszeri

DEBRECENI EGYETEM TÁPLÁLKOZÁS- ÉS ÉLELMISZERTUDOMÁNYI DOKTORI ISKOLA Doktori Iskola vezető: Prof. Dr. Szilvássy Zoltán egyetemi tanár, az MTA doktora Témavezető: Prof. Dr. Sipka Sándor egyetemi tanár, az MTA doktora, Professor Emeritus ROSSZINDULATÚ DAGANATOK ÉS SZÍV– ÉRRENDSZERI BETEGSÉGEK STANDARDIZÁLT HALÁLOZÁSI ARÁNYSZÁMAI MAGYARORSZÁG ÖT BORTERMELÉS SZEMPONTJÁBÓL KÜLÖNBÖZŐ TERÜLETÉN 2000-2010 KÖZÖTT Készítette: Nagy János doktorjelölt Debrecen 2021 ROSSZINDULATÚ DAGANATOK ÉS SZÍV–ÉRRENDSZERI BETEGSÉGEK STANDARDIZÁLT HALÁLOZÁSI ARÁNYSZÁMAI MAGYARORSZÁG ÖT BORTERMELÉS SZEMPONTJÁBÓL KÜLÖNBÖZŐ TERÜLETÉN 2000-2010 KÖZÖTT Értekezés a doktori (PhD) fokozat megszerzése érdekében a táplálkozás- és élelmiszertudomány tudományágban Írta: Nagy János okleveles matematikus Készült a Debreceni Egyetem Táplálkozás- és Élelmiszertudományi és Doktori Iskolája (Élelmiszertudományi doktori programja) keretében Témavezető: Prof. Dr. Sipka Sándor egyetemi tanár, az MTA doktora Az értekezés bírálói: ________________________ ________________________ A bírálóbizottság: elnök: ________________________ tagok: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Az értekezés védésének időpontja: 2021…...………………..…. RÖVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE AADR age-adjusted death rate = standardizált halálozási arányszám BNO betegségek nemzetközi osztályozása CVD cardiovascular diseases = szív és érrendszeri megbetegedések DI deprivációs index EBM evidence based medicine = bizonyíték alapú orvoslás GI gastrointestinalis/gyomor-bélrendszeri -

Chemical and Archaeological Evidence for the Earliest Cacao Beverages

Chemical and archaeological evidence for the earliest cacao beverages John S. Henderson*†, Rosemary A. Joyce‡, Gretchen R. Hall§, W. Jeffrey Hurst¶, and Patrick E. McGovern§ *Department of Anthropology, Cornell University, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853; ‡Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; §Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, PA 19104; and ¶Hershey Foods Technical Center, P.O. Box 805, Hershey, PA 17033 Edited by Joyce Marcus, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and approved October 8, 2007 (received for review September 17, 2007) Chemical analyses of residues extracted from pottery vessels from ical component limited in Central America to Theobroma spp, Puerto Escondido in what is now Honduras show that cacao has been identified elsewhere in visible residues preserved inside beverages were being made there before 1000 B.C., extending the intact pottery vessels of the Classic (mid-1st millennium A.D.) confirmed use of cacao back at least 500 years. The famous and Middle Formative periods (mid-1st millennium B.C.) (5–8). chocolate beverage served on special occasions in later times in Mesoamerica, especially by elites, was made from cacao seeds. The Results earliest cacao beverages consumed at Puerto Escondido were likely Puerto Escondido is a small but wealthy village in the lower Rı´o produced by fermenting the sweet pulp surrounding the seeds. Ulu´a Valley (Fig. 1), where excavation of deeply stratified deposits, buried under several meters of later occupation debris, archaeology ͉ chemistry ͉ Honduras ͉ Mesoamerica has revealed indications of domestic activity beginning before 1500 B.C., near the beginnings of settled village life in Me- everages produced from Theobroma spp. -

Ancient Brews Rediscovered and Re-Created 1St Edition Editions 5

FREE ANCIENT BREWS REDISCOVERED AND RE- CREATED 1ST EDITION PDF Patrick E McGovern | 9780393253801 | | | | | Patrick Edward McGovern - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Ancient Brews by Patrick E. McGovern. Sam Calagione Foreword. Interweaving archaeology and science, Patrick E. Humans invented heady concoctions, experimenting with fruits, honey, cereals, tree resins, botanicals, and more. McGovern describes nine extreme fermented beverages of our ancestors, including the Midas Touch from Turkey and the year-old Chateau Jiahu from Neolithic China, the earliest chemically identified alcoholic drink yet discovered. For the adventuresome, homebrew interpretations of the ancient drinks are provided, with matching meal recipes. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published October 2nd by W. Norton Company first published More Details Ancient Brews Rediscovered and Re-Created 1st edition Editions 5. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Ancient Brewsplease sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Ancient Brews: Rediscovered and Re-created. May 24, Darcey rated it it was ok Shelves: books-i-ownhistorycookbooks-and-food-history. This was a book about the history and archaeology of alcoholic beverages. In theory, this should have been really interesting, but in practice, the book was really poorly written. -

Chemical and Archaeological Evidence for the Earliest Cacao Beverages

Chemical and archaeological evidence for the earliest cacao beverages John S. Henderson*†, Rosemary A. Joyce‡, Gretchen R. Hall§, W. Jeffrey Hurst¶, and Patrick E. McGovern§ *Department of Anthropology, Cornell University, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853; ‡Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; §Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, PA 19104; and ¶Hershey Foods Technical Center, P.O. Box 805, Hershey, PA 17033 Edited by Joyce Marcus, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and approved October 8, 2007 (received for review September 17, 2007) Chemical analyses of residues extracted from pottery vessels from ical component limited in Central America to Theobroma spp, Puerto Escondido in what is now Honduras show that cacao has been identified elsewhere in visible residues preserved inside beverages were being made there before 1000 B.C., extending the intact pottery vessels of the Classic (mid-1st millennium A.D.) confirmed use of cacao back at least 500 years. The famous and Middle Formative periods (mid-1st millennium B.C.) (5–8). chocolate beverage served on special occasions in later times in Mesoamerica, especially by elites, was made from cacao seeds. The Results earliest cacao beverages consumed at Puerto Escondido were likely Puerto Escondido is a small but wealthy village in the lower Rı´o produced by fermenting the sweet pulp surrounding the seeds. Ulu´a Valley (Fig. 1), where excavation of deeply stratified deposits, buried under several meters of later occupation debris, archaeology ͉ chemistry ͉ Honduras ͉ Mesoamerica has revealed indications of domestic activity beginning before 1500 B.C., near the beginnings of settled village life in Me- everages produced from Theobroma spp. -

Enrico CHIORRINI L'odissea Del Vino Tra Miti E Scoperte Archeologiche

Enrico CHIORRINI L’Odissea del vino tra miti e scoperte archeologiche nostrane e internazionali. L’assunzione di bevande alcoliche può dirsi qualcosa di congenito all’umanità e il vino, in particolare, ha creato fin dalla sua scoperta un legame viscerale con l’uomo. Nel tardo Neolitico i primi cacciatori-raccoglitori, per il loro sostentamento, iniziarono a cogliere i frutti di una particolare pianta rampicante: la Vitis vinifera subsp . Sylvestris . Questo frutto ha un processo di fermentazione molto semplice: sono sufficienti alcuni grappoli, pressati e depositati sul fondo di un recipiente, per dare il via, dopo qualche giorno, al processo di fermentazione. Probabilmente il primo vinificatore della storia fu un uomo che, dimenticando alcuni grappoli ammaccati e schiacciati dentro rudimentali recipienti, avviò per caso la fermentazione del loro succo, producendo senza volerlo il primo vino della storia. Da questa scoperta gli uomini iniziarono un processo di selezione delle piante maggiormente produttive per quantità e dimensione dei frutti che portò alla creazione della Vitis vinifera subsp. Vinifera, da cui discendono tutte le tipologie di uvaggio. È impossibile dire con sicurezza in quale parte del mondo avvenne primariamente questa scoperta, dato che la Sylvestris cresceva lungo tutta la fascia temperata dalla Spagna alla Cina. Attualmente le più antiche attestazioni archeobotaniche di tracce fermentative di vite selvatica sono state rinvenute nella provincia cinese di Henan, dall’archeologo Patrick Edward McGovern, e risalgono al 7000 a. C., anticipando di un millennio quella che erroneamente era stata considerata la sua culla per decenni, il Vicino Oriente ed in particolare la regione caucasica. Analizzando i campioni di alcune giare, McGovern ha infatti rilevato tracce di una bevanda fermentata fatta di uva selvatica, riso, biancospino e miele. -

Human Securities, Sustainability, and Migration in the Ancient U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest

Copyright © 2021 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Ingram, S. E., and S. M. Patrick. 2021. Human securities, sustainability, and migration in the ancient U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest. Ecology and Society 26(2):9. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-12312-260209 Synthesis Human securities, sustainability, and migration in the ancient U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest Scott E. Ingram 1 and Shelby M. Patrick 2 ABSTRACT. In the U.S. Southwest and Mexican Northwest region, arid-lands agriculturalists practiced sedentary agriculture for at least four thousand years. People developed diverse lifeways and a repertoire of successful dryland strategies that resemble those of some small-scale agriculturalists today. A multi-millennial trajectory of variable population growth ended during the early 1300s CE and by the late 1400s population levels in the region declined by about one-half. Here we show, through a meta-analysis of sub-regional archaeological studies, the spatial distribution, intensity, and variation in social and environmental conditions throughout the region prior to depopulation. We also find that as these conditions, identified as human insecurities by the UN Development Programme, worsened, the speed of depopulation increased. Although these conditions have been documented within some sub-regions, the aggregate weight and distribution of these insecurities throughout the Southwest/Northwest region were previously unrecognized. Population decline was not the result of a single disturbance, such as drought, to the regional system; it was a spatially patterned, multi-generational decline in human security. Results support the UN’s emphasis on increasing human security as a pathway toward sustainable development and lessening forced migration. -

Facultad De Filosofía Y Letras

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Documental de la Universidad de Valladolid Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Grado en Historia El consumo de vino durante la Edad del Bronce en el mundo minoico Andrea González Horcajada Tutora: Elisa Guerra Doce Curso: 2018-2019 1 2 RESUMEN El presente trabajo pretende estudiar las primeras evidencias sobre la elaboración de vino en el Egeo y posteriormente analizar el incremento de la producción y consumo de esta bebida en el mundo minoico durante la Edad del Bronce. No sólo realizaremos una compilación de todos aquellos vestigios relacionados con su consumición y procesamiento, sino también llevaremos a cabo una lectura social de las implicaciones que el consumo de vino tenía dentro de la sociedad minoica durante el Bronce. PALABRAS CLAVE: Vino, vitivinicultura, Creta, Edad del Bronce, Banquete, Palacios ABSTRACT The present work intends to iniatially study the first evidences about wine-making process in the Aegean and, subsequently, to analyze the production and consumption increase of this beverage in the Minoan world during the Bronze Age. Not only will all those vestiges related to its consumption and processing be complited but a social reading about the implications and consequences that wine consumption had within the Minoian society during the mentioned Bronze Age will be carried out. KEY WORDS Wine, vitiviniculture, Crete, Bronze Age, Feast, Palaces 3 4 ÍNDICE 1.-Introducción .....................................................................................................................7 2.-Los inicios de la viticultura y la vinificación en el Viejo Mundo ....................................9 2.1 La producción de vino ................................................................................................. 12 2.2. -

The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 78 Number 78 Article 4 4-2018 The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World John C. Scott Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Scott, John C. (2018) "The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 78 : No. 78 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol78/iss78/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Scott: The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World Comparative Civilizations Review 25 The Phoenicians and the Formation of the Western World1 John C. Scott A small maritime region, Phoenicia lay on the Eastern Mediterranean coast. The Phoenicians, who were Semites, emerged as a distinct Canaanite group around 3200 B.C. Hemmed in by the Lebanon Mountains, their first cities were Byblos, Sidon, Tyre, and Aradus.2 Scholars agree that there are two sources of the Western tradition: Judeo-Christian doctrine and ancient Greek intellectualism. More generally, there is recognition that Western civilization is largely built atop the Near Eastern civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. A basic question arises, however, as to which ancient people specifically prepared the way for the West to develop. While early Aegean cultures are often viewed as the mainspring, assessment of the growing literature reveals that the city-states of Phoenicia stimulated (Bronze Age) and fostered (Iron Age) Western civilization. -

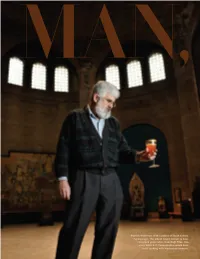

Patrick Mcgovern with a Goblet of Liquid History. Facing Page

MAN, T Patrick McGovern with a goblet of liquid history. Facing page: The oldest vessel known to have contained grape wine, from Hajji Firuz, Iran 34 JAN | FEB 2010 THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE circa 5400 B.C. Fermentation would have set it rocking with mysterious tremors. The Drinker Biomolecular archaeologist and Penn Museum researcher Patrick McGovern Gr’80 has found some of the oldest alcoholic beverages known to history, and he wants you to take a glug. They might just be responsible for civilization as we know it. (Not to mention your next hangover.) By Trey Popp THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE JAN | FEB 2010 35 photography by candace dicarlo THE PENNSYLVANIA GAZETTE JAN | FEB 2010 35 scrum around Sam Calagione’s McGovern, a senior research scientist 700 B.C., has won more awards than any- The keg measured 10 deep, and at the Penn Museum, has spent the last thing else Dogfish Head makes. everyone was angling for a cup laced with two decades on the trail of ancient wines Tonight’s quaff, though, promised to the brewer’s saliva. It was not a secret and beers. Scraping the gunk out of old make its predecessors look tame. It was a ingredient. The drinkers had just heard all cauldrons and pottery sherds, he has South American-style beer called chicha about it in the Penn Museum’s Upper found evidence of alcoholic beverages as made with the help of Clark Erickson, Egyptian Gallery. They’d seen slides. But far apart in space and time as Iron Age associate curator of the Museum’s for fans of extreme fermentation, this was Turkey and Neolithic China. -

Through the Grapevine: Tracing the Origins of Wine

THROUGH THE GRAPEVINE: TRACING THE ORIGINS OF WINE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Luke Gorton, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Carolina López-Ruiz, Advisor Brian Joseph Sam Meier Copyright by Luke A. Gorton 2014 ABSTRACT This study examines the question of the origins and spread of wine, both comprehensively and throughout a number of regions of the Near East and the Mediterranean. Besides the introduction and the conclusion, the study is divided into four major chapters, each of which examines evidence from different fields. The first of these chapters discusses the evidence which can be found in the tomes of classical (that is, Greco-Roman) literature, while the second chapter examines the testimony of the diverse literature of the ancient Near East. The third chapter provides an analysis of the linguistic evidence for the spread of wine, focusing particularly on the origins of the international word for wine which is present in a number of different languages (and language families) of antiquity. The fourth chapter gives a summary of the various types of material evidence relevant to wine and the vine in antiquity, including testimony from the fields of palaeobotany, archaeology, and wine chemistry. Finally, the concluding chapter provides a synthesis of the various data adduced in the previous chapters, weaving all of the evidence together into a cohesive account of the origins and the spread of wine. It is seen that each discipline has much to contribute to the question at hand, providing critical testimony which both illuminates our understanding of the origins and the spread of wine and allows us to better understand issues pertaining to each discipline. -

Üzümün Akdeniz'deki Yolculuğu

Akdeniz, fiziki bir coğrafya olmanın ötesinde uygarlıklar coğrafyasıdır. Bu bağlamda bir ÜZÜMÜN buluşma/ayrışma, uyum/çatışma, üretim/tüketim, yayılma/kapanma, büyüme/kriz, coğrafyası olagelmiştir. Fiziki AKDENİZ’DEKİ coğrafyanın uygarlıklarla kesişme noktasında, tarım temel bir dinamiktir. Akdeniz hikayesinde, Fernand Braudel’in de belirttiği gibi buğday, zeytin ve üzüm temel YOLCULUĞU ürünlerdir. Bu ürünler, tarımsal ürün olmanın dışında toplumsal hayatın farklı bir çok KONFERANS BİLDİRİLERİ noktasını kesmektedirler. İzmir Akdeniz Akademisi, İzmir tarihini Akdeniz perspektifiyle yeninden düşünmek için Akdeniz'in temel ürünlerinin, günümüze kadar uzanan tarihsel serüvenini ele alan konferans BİLDİRİLERİ KONFERANS dizileri düzenliyor. Bu kitap, Akdeniz'in tarihsel hikayesini bugünle birleştirerek üzüm, bağcılığın toplumsal ve ekonomik boyutlarını ele alan konferanslar dizisinin bir ürünüdür. ÜZÜMÜN AKDENİZ’DEKİ YOLCULUĞU ÜZÜMÜN AKDENİZ’DEKİ YOLCULUĞU “KONFERANS BİLDİRİLERİ” ÜZÜMÜN AKDENİZ’DEKİ YOLCULUĞU “KONFERANS BİLDİRİLERİ” İzmir Büyükşehir Belediyesi Akdeniz Akademisi Mehmet Ali Akman Mah. Mithatpaşa Cad. No: 1087, 35290 Konak-İzmir Tel: 0232 293 46 13 Faks: 0232 293 46 10 Sertifika No: 22595 Yayına Hazırlayan Ertekin Akpınar Yayın Koordinasyonu Ece Aytekin Büker Editörler Ertekin Akpınar Ekrem Tükenmez Son Okuma Doç. Dr. Alp Yücel KAYA Çeviri Dr. Mehmet Kuru Kapak ve Grafik Tasarım Murat Hürel Çobanoğlu Fotoğraflar Konuşma metinlerinin içindeki fotoğraf, grafik ve tablolar yazarların kişisel arşivine aittir. 166. sayfa fotoğrafı Ekrem Tükenmez'den, diğer fotoğraflar, 123rf fotoğraf arşivi sitesinden telif ödenmek suretiyle alınmıştır. Baskı Dinç Ofset Matbaa - 145/4 Sokak No:11/C Yenişehir - İzmir Tel & Fax: 0232 459 49 61- 63 Sertifika No: 20558 Birinci Baskı 1500 Adet, Aralık 2017 ISBN: 978-975-18-0239-2 Bu kitapta yayınlanan bildiriler, yazarların kişisel görüşünü yansıtır. Bu kitap, İzmir Akdeniz Akademisi tarafından yayına hazırlanmış olup, İzmir Büyükşehir Belediyesi’nin ücretsiz kültür hizmetidir.