Phoenicians: the Quickening of Western Civilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fermented Beverages of Pre- and Proto-Historic China

Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China Patrick E. McGovern*†, Juzhong Zhang‡, Jigen Tang§, Zhiqing Zhang¶, Gretchen R. Hall*, Robert A. Moreauʈ, Alberto Nun˜ ezʈ, Eric D. Butrym**, Michael P. Richards††, Chen-shan Wang*, Guangsheng Cheng‡‡, Zhijun Zhao§, and Changsui Wang‡ *Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA), University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia, PA 19104; ‡Department of Scientific History and Archaeometry, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui 230026, China; §Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing 100710, China; ¶Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology of Henan Province, Zhengzhou 450000, China; ʈEastern Regional Research Center, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wyndmoor, PA 19038; **Firmenich Corporation, Princeton, NJ 08543; ††Department of Human Evolution, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, 04103 Leipzig, Germany; and ‡‡Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 10080, China Communicated by Ofer Bar-Yosef, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, November 16, 2004 (received for review September 30, 2003) Chemical analyses of ancient organics absorbed into pottery jars A much earlier history for fermented beverages in China has long from the early Neolithic village of Jiahu in Henan province in China been hypothesized based on the similar shapes and styles of have revealed that a mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey, and Neolithic pottery vessels to the magnificent Shang Dynasty bronze fruit (hawthorn fruit and͞or grape) was being produced as early as vessels (8), which were used to present, store, serve, drink, and the seventh millennium before Christ (B.C.). This prehistoric drink ritually present fermented beverages during that period. -

Rosszindulatú Daganatok És Szív– Érrendszeri

DEBRECENI EGYETEM TÁPLÁLKOZÁS- ÉS ÉLELMISZERTUDOMÁNYI DOKTORI ISKOLA Doktori Iskola vezető: Prof. Dr. Szilvássy Zoltán egyetemi tanár, az MTA doktora Témavezető: Prof. Dr. Sipka Sándor egyetemi tanár, az MTA doktora, Professor Emeritus ROSSZINDULATÚ DAGANATOK ÉS SZÍV– ÉRRENDSZERI BETEGSÉGEK STANDARDIZÁLT HALÁLOZÁSI ARÁNYSZÁMAI MAGYARORSZÁG ÖT BORTERMELÉS SZEMPONTJÁBÓL KÜLÖNBÖZŐ TERÜLETÉN 2000-2010 KÖZÖTT Készítette: Nagy János doktorjelölt Debrecen 2021 ROSSZINDULATÚ DAGANATOK ÉS SZÍV–ÉRRENDSZERI BETEGSÉGEK STANDARDIZÁLT HALÁLOZÁSI ARÁNYSZÁMAI MAGYARORSZÁG ÖT BORTERMELÉS SZEMPONTJÁBÓL KÜLÖNBÖZŐ TERÜLETÉN 2000-2010 KÖZÖTT Értekezés a doktori (PhD) fokozat megszerzése érdekében a táplálkozás- és élelmiszertudomány tudományágban Írta: Nagy János okleveles matematikus Készült a Debreceni Egyetem Táplálkozás- és Élelmiszertudományi és Doktori Iskolája (Élelmiszertudományi doktori programja) keretében Témavezető: Prof. Dr. Sipka Sándor egyetemi tanár, az MTA doktora Az értekezés bírálói: ________________________ ________________________ A bírálóbizottság: elnök: ________________________ tagok: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ Az értekezés védésének időpontja: 2021…...………………..…. RÖVIDÍTÉSEK JEGYZÉKE AADR age-adjusted death rate = standardizált halálozási arányszám BNO betegségek nemzetközi osztályozása CVD cardiovascular diseases = szív és érrendszeri megbetegedések DI deprivációs index EBM evidence based medicine = bizonyíték alapú orvoslás GI gastrointestinalis/gyomor-bélrendszeri -

Chemical and Archaeological Evidence for the Earliest Cacao Beverages

Chemical and archaeological evidence for the earliest cacao beverages John S. Henderson*†, Rosemary A. Joyce‡, Gretchen R. Hall§, W. Jeffrey Hurst¶, and Patrick E. McGovern§ *Department of Anthropology, Cornell University, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853; ‡Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; §Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, PA 19104; and ¶Hershey Foods Technical Center, P.O. Box 805, Hershey, PA 17033 Edited by Joyce Marcus, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and approved October 8, 2007 (received for review September 17, 2007) Chemical analyses of residues extracted from pottery vessels from ical component limited in Central America to Theobroma spp, Puerto Escondido in what is now Honduras show that cacao has been identified elsewhere in visible residues preserved inside beverages were being made there before 1000 B.C., extending the intact pottery vessels of the Classic (mid-1st millennium A.D.) confirmed use of cacao back at least 500 years. The famous and Middle Formative periods (mid-1st millennium B.C.) (5–8). chocolate beverage served on special occasions in later times in Mesoamerica, especially by elites, was made from cacao seeds. The Results earliest cacao beverages consumed at Puerto Escondido were likely Puerto Escondido is a small but wealthy village in the lower Rı´o produced by fermenting the sweet pulp surrounding the seeds. Ulu´a Valley (Fig. 1), where excavation of deeply stratified deposits, buried under several meters of later occupation debris, archaeology ͉ chemistry ͉ Honduras ͉ Mesoamerica has revealed indications of domestic activity beginning before 1500 B.C., near the beginnings of settled village life in Me- everages produced from Theobroma spp. -

Ancient Brews Rediscovered and Re-Created 1St Edition Editions 5

FREE ANCIENT BREWS REDISCOVERED AND RE- CREATED 1ST EDITION PDF Patrick E McGovern | 9780393253801 | | | | | Patrick Edward McGovern - Wikipedia Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Ancient Brews by Patrick E. McGovern. Sam Calagione Foreword. Interweaving archaeology and science, Patrick E. Humans invented heady concoctions, experimenting with fruits, honey, cereals, tree resins, botanicals, and more. McGovern describes nine extreme fermented beverages of our ancestors, including the Midas Touch from Turkey and the year-old Chateau Jiahu from Neolithic China, the earliest chemically identified alcoholic drink yet discovered. For the adventuresome, homebrew interpretations of the ancient drinks are provided, with matching meal recipes. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published October 2nd by W. Norton Company first published More Details Ancient Brews Rediscovered and Re-Created 1st edition Editions 5. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. To ask other readers questions about Ancient Brewsplease sign up. Lists with This Book. This book is not yet featured on Listopia. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 3. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of Ancient Brews: Rediscovered and Re-created. May 24, Darcey rated it it was ok Shelves: books-i-ownhistorycookbooks-and-food-history. This was a book about the history and archaeology of alcoholic beverages. In theory, this should have been really interesting, but in practice, the book was really poorly written. -

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires

Quantitative Dynamics of Human Empires Cesare Marchetti and Jesse H. Ausubel FOREWORD Humans are territorial animals, and most wars are squabbles over territory. become global. And, incidentally, once a month they have their top managers A basic territorial instinct is imprinted in the limbic brain—or our “snake meet somewhere to refresh the hierarchy, although the formal motives are brain” as it is sometimes dubbed. This basic instinct is central to our daily life. to coordinate business and exchange experiences. The political machinery is Only external constraints can limit the greedy desire to bring more territory more viscous, and we may have to wait a couple more generations to see a under control. With the encouragement of Andrew Marshall, we thought it global empire. might be instructive to dig into the mechanisms of territoriality and their role The fact that the growth of an empire follows a single logistic equation in human history and the future. for hundreds of years suggests that the whole process is under the control In this report, we analyze twenty extreme examples of territoriality, of automatic mechanisms, much more than the whims of Genghis Khan namely empires. The empires grow logistically with time constants of tens to or Napoleon. The intuitions of Menenius Agrippa in ancient Rome and of hundreds of years, following a single equation. We discovered that the size of Thomas Hobbes in his Leviathan may, after all, be scientifically true. empires corresponds to a couple of weeks of travel from the capital to the rim We are grateful to Prof. Brunetto Chiarelli for encouraging publication using the fastest transportation system available. -

Study Guide #16 the Rise of Macedonia and Alexander the Great

Name_____________________________ Global Studies Study Guide #16 The Rise of Macedonia and Alexander the Great The Rise of Macedonia. Macedonia was strategically located on a trade route between Greece and Asia. The Macedonians suffered near constant raids from their neighbors and became skilled in horseback riding and cavalry fighting. Although the Greeks considered the Macedonians to be semibarbaric because they lived in villages instead of cities, Greek culture had a strong influence in Macedonia, particularly after a new Macedonian king, Philip II, took the throne in 359 B.C. As a child, Philip II had been a hostage in the Greek city of Thebes. While there, he studied Greek military strategies and learned the uses of the Greek infantry formation, the phalanx. After he left Thebes and became king of Macedonia, Philip used his knowledge to set up a professional army consisting of cavalry, the phalanx, and archers, making the Macedonian army one of the strongest in the world at that time. Philip’s ambitions led him to conquer Thrace, to the east of Macedonia. Then he moved to the trade routes between the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea. Soon Philip turned his attention to the Greek citystates. Although some Greek leaders tried to get the city-states to unite, they were unable to forge a common defense, which made them vulnerable to the Macedonian threat. Eventually, Philip conquered all the city-states, including Athens and Thebes, which he defeated at the battle of Chaeronea in 338 B.C. This battle finally ended the independence of the Greek city-states. -

THE NATURE of the THALASSOCRACIES of the SIXTH-CENTURY B. C. by CATHALEEN CLAIRE FINNEGAN B.A., University of British Columbia

THE NATURE OF THE THALASSOCRACIES OF THE SIXTH-CENTURY B. C. by CATHALEEN CLAIRE FINNEGAN B.A., University of British Columbia, 1973 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of CLASSICS We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October, 1975 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my writ ten pe rm i ss ion . Department of plassips. The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date October. 197 5. ~t A ~ A A P. r~ ii The Nature of the Thalassocracies of the Sixth-Century B. C. ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to study the nature and extent of the sixth century thalassocracies through the available ancient evidence, particularly the writings of Herodotus and Thucydides. In Chapter One the evidence for their existence is established and suggested dates are provided. Chapter Two is a study of their naval aspects and Chapter Three of their commercial aspects. This study leads to the conclusion that these thalassocracies were unaggressive mercantile states, with the exception of Samos during Polycrates' reign. -

Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey

Oral Tradition, 31/1 (2017):3-50 Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey Gregory Nagy Introduction I explore here the kaleidoscopic world of Homer and Homeric poetry from a diachronic perspective, combining it with a synchronic perspective. The terms synchronic and diachronic, as I use them here, come from linguistics.1 When linguists use the word synchronic, they are thinking of a given structure as it exists in a given time and space; when they use diachronic, they are thinking of that structure as it evolves through time.2 From a diachronic perspective, the structure that we know as Homeric poetry can be viewed, I argue, as an evolving medium. But there is more to it. When you look at Homeric poetry from a diachronic perspective, you will see not only an evolving medium of oral poetry. You will see also a medium that actually views itself diachronically. In other words, Homeric poetry demonstrates aspects of its own evolution. A case in point is “the Cretan Odyssey”—or, better, “a Cretan Odyssey”—as reflected in the “lying tales” of Odysseus in the Odyssey. These tales, as we will see, give the medium an opportunity to open windows into an Odyssey that is otherwise unknown. In the alternative universe of this “Cretan Odyssey,” the adventures of Odysseus take place in the exotic context of Minoan-Mycenaean civilization. Part 1: Minoan-Mycenaean Civilization and Memories of a Sea-Empire3 Introduction From the start, I say “Minoan-Mycenaean civilization,” not “Minoan” and “Mycenaean” separately. This is because elements of Minoan civilization become eventually infused with elements we find in Mycenaean civilization. -

Chemical and Archaeological Evidence for the Earliest Cacao Beverages

Chemical and archaeological evidence for the earliest cacao beverages John S. Henderson*†, Rosemary A. Joyce‡, Gretchen R. Hall§, W. Jeffrey Hurst¶, and Patrick E. McGovern§ *Department of Anthropology, Cornell University, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, NY 14853; ‡Department of Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; §Museum Applied Science Center for Archaeology, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, PA 19104; and ¶Hershey Foods Technical Center, P.O. Box 805, Hershey, PA 17033 Edited by Joyce Marcus, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, and approved October 8, 2007 (received for review September 17, 2007) Chemical analyses of residues extracted from pottery vessels from ical component limited in Central America to Theobroma spp, Puerto Escondido in what is now Honduras show that cacao has been identified elsewhere in visible residues preserved inside beverages were being made there before 1000 B.C., extending the intact pottery vessels of the Classic (mid-1st millennium A.D.) confirmed use of cacao back at least 500 years. The famous and Middle Formative periods (mid-1st millennium B.C.) (5–8). chocolate beverage served on special occasions in later times in Mesoamerica, especially by elites, was made from cacao seeds. The Results earliest cacao beverages consumed at Puerto Escondido were likely Puerto Escondido is a small but wealthy village in the lower Rı´o produced by fermenting the sweet pulp surrounding the seeds. Ulu´a Valley (Fig. 1), where excavation of deeply stratified deposits, buried under several meters of later occupation debris, archaeology ͉ chemistry ͉ Honduras ͉ Mesoamerica has revealed indications of domestic activity beginning before 1500 B.C., near the beginnings of settled village life in Me- everages produced from Theobroma spp. -

Sample File Heavily on Patriotism and National Identity

Empire Builder Kit Preface ............................................................ 2 Government Type Credits & Legal ................................................ 2 An empire has it rulers. The type of ruler can How to Use ..................................................... 2 often determine the character of a nation. Are Government Types ......................................... 3 they a democratic society that follows the will Simple Ruler Type ....................................... 3 of the people, or are they ruled by a harsh dictator who demand everyone caters to their Expanded Ruler Type .................................. 4 every whim. They could even be ruled by a Also Available ................................................ 10 group of industrialists whose main goal is the acquisition of wealth. Coming Soon ................................................. 10 This part of the Empire Builder kit outlines some of the more common, and not so common, types of ruler or government your empire or country may possess. Although designed with fantasy settings in mind, most of the entries can be used in a sci-fi or other genre of story or game. There are two tables in this publication. One for simple and quick governments and A small disclaimer – A random generator will another that is expanded. Use the first table never be as good as your imagination. Use for when you want a common government this to jump start your own ideas or when you type or a broad description, such as need to fill in the blank. democracy or monarchy. Use the second/expanded table for when you want something that is rare or you want more Sample details,file such as what type of democracy etc. If you need to randomly decide between the two tables, then roll a d20. If you get 1 – 18 then use the simple table, otherwise use the expanded one. -

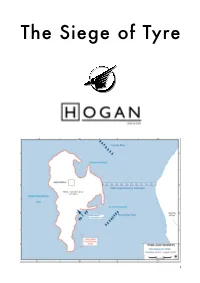

The Siege of Tyre

The Siege of Tyre 1 Contents Past Questions! 2 Arrian’s Account Of The Siege! 4 Key Points! 14 Past Questions 1985 Give Alexander's reasons for besieging Tyre and describe the siege. What does the siege tell us about Alexander's character? (50) 1991 "Alexander had no difficulty in persuading his officers that the attempt on Tyre must be made". (Arrian, Book 2. Ch. 18) What arguments did Alexander use to persuade his officers? What factors made the siege of Tyre “a tremendous undertaking"? (50) 1995 2 What particular skills did Alexander show in his sieges of Halicarnassus and Tyre? (50) 2004 (ii) The siege and capture of Tyre has been described as Perhaps the hardest task that Alexander’s military genius ever encountered. (Bury and Meiggs) (a) What were the main challenges presented by Tyre and its defenders, and how did Alexander’s genius overcome those challenges? (40) (b) What is your opinion of Alexander’s treatment of the survivors after the capture of Tyre? (10) 2012 (ii) (a) Explain why the city of Tyre was so difficult to capture. (15) (b) How did Alexander overcome the difficulties presented by Tyre and its defenders? (25) (c) What do you learn about Alexander’s character from Arrian’s account of the siege and capture of Tyre? (10) 3 Arrian’s Account Of The Siege • Alexander easily persuaded his men to make an attack on Tyre. An omen helped to convince him, because that very night during a dream he seemed to be approaching the walls of Tyre, and Heracles was stretching out his right hand towards him and leading him to the city. -

Athenian Democratic Ideology

Athenian Democratic Ideology We aim to bring together scholars interested in the rhetorical devices, media, and techniques used to promote or attack political ideologies or achieve political agendas during fifth- and fourth-century BCE Athens. A senior scholar with expertise in this area has agreed to preside over the panel and facilitate discussion. “Imperial Society and Its Discontents” investigates challenges to an important aspect of Athenian imperial ideology, namely pride in the fleet’s ability to keep Athens fed and the empire secure during the so-called First Peloponnesian War and the Peloponnesian War proper. The author takes on Ober’s (1998) minimizing of the role the empire played in enabling the democracy’s existence. The author focuses on Herodotus’ Aces River vignette (Book 3), in which the Persians employ heavy-handed imperial methods to control water resources. Given the Athenians’ adoption of forms of oriental despotism in their own imperial practices (Raaflaub 2009), Herodotus plays the role of ‘tragic warner,’ intending that this story serve as a negative commentary on Athenian imperialism. Moving from the empire to the dêmos, “The Importance of Being Honest: Truth in the Attic Courtroom” examines whether legal proceedings in Athens were “honor games” (Humphreys 1985; Osborne 1985) or truly legitimate legal proceedings (Harris 2005). The author argues that both assertions are correct, because while honor games were being played, the truth of the charges still was of utmost importance. Those playing “honor games” had to keep to the letter of the law, as evidence from Athenian oratory demonstrates. The prosecutor’s honesty was a crucial part of these legal proceedings, and any honor rhetoric went far beyond mere status-seeking.