Cross-Border Financial Services: Europe's Cinderella?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

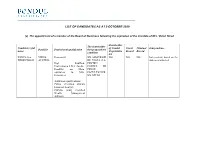

OGM 2. List of Candidates As at 9 October 2020

___________________________________________________________________________________________________ LIST OF CANDIDATES AS AT 9 OCTOBER 2020 (a) The appointment of a member of the Board of Nominees following the expiration of the mandate of Mrs. Vivian Nicoli Shareholder The shareholder Candidate’s full of Fondul Fiscal Criminal Independence Domicile Professional qualification that proposed the name Proprietatea Record Record candidate SA ILINCA von VIENA, Economist NN ASIGURARI NO NO NO Independent, based on the DERENTHALL AUSTRIA DE VIATA S.A. statement attached Dipl. Kauffrau, PENTRU Universitatea J.W.v. Goethe, FONDUL DE Frankfurt am Main, PENSII equivalent to MSc. FACULTATIVE Economics NN OPTIM Additional qualifications: CEFA (Certified EFFAS Financial Analyst), CWMA (SAQ Certified Wealth Management Advisor) ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ (b) The appointment of a member of the Board of Nominees following the expiration of the mandate of Mr. Steven van Groningen Shareholder Independence The shareholder Candidate’s full of Fondul Fiscal Criminal Professional qualification that proposed the name Domicile Proprietatea Record Record candidate SA OVIDIU FER BUCHAREST, Economist J&T Banka NO NO NO The Sole Director does ROMANIA believe Mr. Ovidiu Fer Academy of Economic may not meet the Studies – Romania, Major independence conditions in Finance, Insurance, because of the partnership Banking and Stock with a former Exchange representative of Fondul Proprietatea SA and INSEAD, -

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES CITY LIVES Martin Gordon Interviewed

NATIONAL LIFE STORIES CITY LIVES Martin Gordon Interviewed by Louise Brodie C409/134 This interview and transcript is accessible via http://sounds.bl.uk. © The British Library Board. Please refer to the Oral History curators at the British Library prior to any publication or broadcast from this document. Oral History The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB United Kingdom +44 (0)20 7412 7404 [email protected] Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of this transcript, however no transcript is an exact translation of the spoken word, and this document is intended to be a guide to the original recording, not replace it. Should you find any errors please inform the Oral History curators Martin Gordon C409/134/F5288-A/Part 1 F5288 Side A [This is the 8th of August 1996. Louise Brodie talking to Martin Gordon.] Could you tell me where and when you were born please? I was born on the 19th of July 1938, the year of the Tiger. I was born in Kensington, in St. Mary Abbot's Terrace. My father was an economist. And, my father had been born in Italy at the beginning of the century; my mother had been born in China in 1913, where her father had been practising as a doctor in Manchuria. Therefore I came from a very international background, albeit my family was a Scottish-English family and I was born in London, but I always had a very strong international inclination from my parents and from other members of my family around the world. -

Journal Association of Jewish Refugees

VOLUME 7 NO.4 APRIL 2007 journal Association of Jewish Refugees Prisoners remembered, prisoners forgotten Researching my article on Herbert Sulzbach captives persisted down the decades. for our February issue, I was amazed at the This fascination does not extend to extent to which the history of German British PoWs in the First World War, about prisoners-of-war in Britain has fallen into whom very little is knovro. At most, a few oblivion. Today, nobody seems to know that people will have heard of the camp at there were some 400,000 German PoWs in Ruhleben, near Berlin, where British Britain in 1946, dispersed all over the civilians were interned. The presence of country in some 1,500 camp units. I even numerous British and French PoWs in discovered a mini-camp in Brondesbury Germany during the First World War also Park, London NW6, about two miles from vanished rapidly from German public where I live, where prisoners from Wilton consciousness, unlike that of Russian PoWs, Park in Buckinghamshire, selected to whose suffering is vividly depicted in such broadcast on the BBC, were lodged in bestsellers as Amold Zweig's Der Streit um London. Yet the record of the British in re den Sergeanten Grischa and E. M. educating the PoWs in their charge was Remarque's Im Westen nichts Neues. The thoroughly creditable. The official German fate of the Russian PoWs came to symbolise history of German PoWs in the Second the senseless suffering of the ordinary World War explicitly acknowledges that soldier in a hopeless war, which was the Britain surpassed all other custodian powers main lesson of the First World War for in teaching PoWs to respect democratic liberal intellectuals in post-1918 Germany. -

The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Rckblicke, by Dr. Rer. Pol. Walter Grnfeld ** This Is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg Ebook, Deta

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rckblicke, by Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld ** This is a COPYRIGHTED Project Gutenberg eBook, Details Below ** ** Please follow the copyright guidelines in this file. ** Copyright (C) 1998 by Frank Dekker This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Rckblicke Author: Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld Release Date: December, 2004 [EBook #7049C] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on February 28, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: German Character set encoding: Latin-1 *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, RUECKBLICKE, BY GRUENFELD *** Copyright (C) 1998 by Frank Dekker Rckblicke Dr. rer. pol. Walter Grnfeld Inhaltsverzeichnis Kapitel 1 Frhes Panorama und Vorgeschichte Kapitel 2 Die Familie und Kattowitz Kapitel 3 Kindheit und frhe Jugend Kapitel 4 Kattowitz kommt zu Polen Kapitel 5 Als Student in der Weimarer Republik A) Berlin a) Leben und Studium b) ... und politische Bettigung B) Mnchen C) Zwischen Breslau und zu Hause Kapitel 6 Nach dem Ende von Weimar Kapitel 7 Emigration nach Hause, in Polen Kapitel 8 Der 2. -

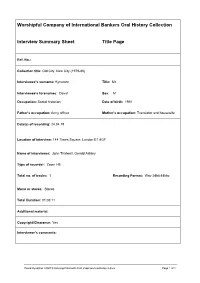

Transcript of Interview with David Kynaston (Historian)

Worshipful Company of International Bankers Oral History Collection Interview Summary Sheet Title Page Ref. No.: Collection title: Old City, New City (1979-86) Interviewee’s surname: Kynaston Title: Mr Interviewee’s forenames: David Sex: M Occupation: Social historian Date of birth: 1951 Father’s occupation: Army officer Mother’s occupation: Translator and housewife Date(s) of recording: 24.04.19 Location of interview: 144 Times Square, London E1 8GF Name of interviewer: John Thirlwell, Gerald Ashley Type of recorder: Zoom H5 Total no. of tracks: 1 Recording Format: Wav 24bit 48khz Mono or stereo: Stereo Total Duration: 01:03:11 Additional material: Copyright/Clearance: Yes Interviewer’s comments: David Kynaston 240419 transcript final with front sheet and endnotes-3.docx Page 1 of 1 Introduction and biography #00:00:00# A club no more: changes from the pre-1980’s village; the #00:0##### aluminium war; Lord Cobbold #00:07:36# Factors of change and external pressures; effects of the abolition of Exchange Control; minimum commissions and single and dual capacity The Stock Exchange ownership question; opening ip to #00:12:17# foreign competition; silly prices paid for firms Cazenove & Co – John Kemp-Welch on partnership and #00:14:57# trust; US capital; Cazenove capital raising Motivations of Big Bang; Philips & Drew; John Craven and #00:18:22# ‘top dollar’ Lloyd’s of London #00:22:26# Bank of England; Margaret Thatcher’s view of the City and #00:25:07# vice versa and her relationship with the Governor, Lord Cobbold Robin Leigh-Pemberton -

1914 and 1939

APPENDIX PROFILES OF THE BRITISH MERCHANT BANKS OPERATING BETWEEN 1914 AND 1939 An attempt has been made to identify as many merchant banks as possible operating in the period from 1914 to 1939, and to provide a brief profle of the origins and main developments of each frm, includ- ing failures and amalgamations. While information has been gathered from a variety of sources, the Bankers’ Return to the Inland Revenue published in the London Gazette between 1914 and 1939 has been an excellent source. Some of these frms are well-known, whereas many have been long-forgotten. It has been important to this work that a comprehensive picture of the merchant banking sector in the period 1914–1939 has been obtained. Therefore, signifcant efforts have been made to recover as much information as possible about lost frms. This listing shows that the merchant banking sector was far from being a homogeneous group. While there were many frms that failed during this period, there were also a number of new entrants. The nature of mer- chant banking also evolved as stockbroking frms and issuing houses became known as merchant banks. The period from 1914 to the late 1930s was one of signifcant change for the sector. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), 361 under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 B. O’Sullivan, From Crisis to Crisis, Palgrave Studies in the History of Finance, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96698-4 362 Firm Profle T. H. Allan & Co. 1874 to 1932 A 17 Gracechurch St., East India Agent. -

Bonds Without Borders a History of the Eurobond Market

Bonds without Borders A History of the Eurobond Market CHRIS O’MALLEY Foreword by Hans-Joerg Rudloff Bonds Without Borders For other titles in the Wiley Finance series please see www.wiley.com/finance Bonds Without Borders A History of the Eurobond Market CHRIS O’MALLEY This edition first published 2015 © 2015 Chris O’Malley Registered office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com. The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com. -

Ready Been Involved in a Daring Attack on Two of the Oligopolists in the German Steel Industry, Mannesman and Thyssen

The London Institute of Banking & Finance Henry Grunfeld Lecture, 22 January 2016 Who was Henry Grunfeld, really? Remarks by his grandson, James Lewisohn On Wednesday 20th January 2016 The London Institute of Banking & Finance was proud to welcome Dr. Alexander Ljunqvist to give the inaugural Henry Grunfeld Lecture. We were honoured that Mr. Grunfeld's grandson James Lewisohn was able to say a few words beforehand to give us an insight into his grandfather's eventful life and unique world view. The text of his address is below. Good evening. I’d like to thank Alex Fraser and The London Institute of Banking & Finance for inviting me to introduce Henry Grunfeld to you. The first thing you need to know is he would have no interest in the current debate on the appropriate State pension age: he started working in Germany aged just 17 and stopped in London over seven decades later when he was 95. I’ve promised Alex not to speak for more than 5 minutes – which gives me three seconds for each year of his life. So please excuse my sins of compression – these are going to be considerable. As a timesaving ruse I’m going to use the Warburg’s abbreviation of his name: HG. I am sure HG would be thrilled to know this event is taking place tonight. Alexander Ljungqvist is going to speak to us about contemporary threats to shareholder capitalism. HG would feel right at home with this theme, since as we will see, he felt his character was formed by the series of economic and political crises – and momentous changes – he worked through. -

A PHILOSOPHY for OFFSHORE ESTATE PLANNING Oscar Wilde Said

A PHILOSOPHY FOR OFFSHORE ESTATE PLANNING Oscar Wilde said: “The only thing to do with good advice is to pass it on. It is never of any use to oneself”. I believe I am doing just that and I would recommend this compact cornucopia to anyone who is dipping their toe into offshore financial waters for the first time. “There are only two qualities in the world: efficiency and inefficiency, and only two sorts of people: the efficient and the inefficient”. Certainly in the case of business I would agree with George Bernard Shaw and most of my readers need to be mindful of this fact when choosing who will assist them with their offshore endeavours. Sometimes, however, it is not as straightforward as Shaw suggests because the efficient can derail themselves and lose their hard-earned reputations by failing to recognise the need to strike the right balance between capability and capacity; so don’t rely on a reputation earned in years past because it might be all that they’re trading on. Following the car manufacturer’s problems with safety failures in 2010, Akio Toyoda, president of Toyota Motor Corporation, made two statements which have universal application, whatever the widget might be. Firstly, he said: “We pursued growth over the speed at which we were able to develop our people and our organisation” and, secondly, that in future he would see to it that “members of the management team actually drive the cars”. Despite the Japanese philosophy of “kaizen” (constant improvement through small, positive steps) quality in this instance, notwithstanding the skill of the workers, played hostage to quantity; proficiency was sacrificed for profit. -

High Financier: Sir Siegmund Warburg and the Art of Relationship Banking Transcript

High Financier: Sir Siegmund Warburg and the Art of Relationship Banking Transcript Date: Wednesday, 2 June 2010 - 12:00AM Location: Museum of London High Financier: Sir Siegmund Warburg and the Art of Relationship Banking Professor Kenneth Costa Gresham Professor of Commerce 02/06/2010 1. Introduction Good evening. Thank you for coming to this last lecture in my series. It is a particular honour to be sharing the platform with Niall Ferguson. Niall is not just a distinguished historian. He is the official biographer of Sir Siegmund Warburg, whose enduring contribution to finance and how that can inform the debate about banking in the current turmoil is my starting point tonight. Warburgs were brave enough to employ me - theology is not the first recruitment ground for bankers! - and I spent a good part of my working life at the bank he founded. My personal experience will therefore colour what I have to say. But I believe that offers us some valuable pointers as to the future of banking at a critical time for finance generally. The essence of the experience is in this lecture's title: High Financier: Sir Siegmund Warburg and the Art of Relationship Banking. As a young banker fresh from university, I had a lot to learn about relationship banking - and I think we would all do well to re-learn the lesson. And it is an art not a science. Sir Siegmund insisted on knowing the client in almost intimate detail. He famously remarked that if you want someone to be a client you should make him your friend first. -

Transcripts of the Interviews of Oscar Lewisohn, Revised by Oscar Lewisohn

Interviewee: Oscar Lewisohn Date: 14th December 2018 Interviewers: John Thirlwell (Q1) and Gerald Ashley (Q2) [00’00 Introduction and biography; banking – R Henriques Jr., Copenhagen, SG Warburg & Co. Limited, London (1962-95)] Q1: Interview with Oscar Lewisohn, interviewees John Thirlwell and Gerald Ashley, 14th December 2018. Oscar, the first question on what year were you born? A: Well, I’ll give you not only the year but the date, 6th May 1938, in Copenhagen, Denmark. Q1: Thank you and what did your parents do? A: My father was a director and manager of a business in Copenhagen that processed raw materials for the manufacture of high-quality duvets and eiderdown and feathers. My mother looked after her four children of whom I am the youngest. Q1: And where you were educated? A: I was educated in Copenhagen and I left school, Sortedam Gymnasium in 1954. It was an excellent institution from which many other young Danes graduated. I then spent three years as a management trainee with Hans F. Caroe Ltd, a general trading business dealing in grain, retail and wholesale food products. In the evenings, I attended a business academy, specialising in commercial German and English, accountancy and Danish commercial law. Consecutive annual summer holidays were spent studying German in Eutin (Schleswig-Holstein, Germany); French in Tours (France) and Spanish in Santander (Spain). Q1: And then from there into banking... A: After that period, I was offered a traineeship at R Henriques Jr., Copenhagen, at that time, the only ranking investment bank in Denmark that was an adviser to the Kingdom of Denmark on its international debt issues, together with Danske Bank, Copenhagen Handelsbanken and Privatbanken. -

The Association of Jewish Refugees/ British Academy Appeal

VOLUME 12 NO.11 novEMBER 2012 The Association of Jewish Refugees/ British Academy Appeal nclosed with this month’s issue, recipient institution. the classicist Maurice Bowra, the art his- readers will find a funding appeal The British Academy, which received torian Kenneth Clark, the archaeologist Eissued jointly in the names of the its Royal Charter from King Edward VII Mortimer Wheeler and the historians Association of Jewish Refugees and the in 1902, is the most prestigious British Alan Bullock, A. J. P. Taylor and Max Be- British Academy. It is now nearly 50 years institution that supports and promotes the loff, among a host of other famous names. since the two organisations were first humanities and social sciences. One of the Current fellows include George Steiner, formally associated, through the Thank- great national learned societies, it occupies the literary scholar, the historian David You Britain Fund, which the AJR set up a place in those fields comparable to that Cannadine, the classicist Mary Beard, in 1963 and which was so successful that of the august Royal Society in the sciences. the political scientist Vernon Bogdanor it raised the sum of £96,000, principally The Academy is one of the leading bodies (David Cameron’s tutor at Oxford), the from the refugees from Nazism who had that funds research in the arts and social archaeologist Barry Cunliffe, the philo- fled to Britain. sciences in Britain, across a wide range sopher Roger Scruton, the professor of A cheque for this amount, worth almost of academic disciplines from history, linguistics David Crystal, and the political £1 million in today’s money, was philosopher Quentin Skinner.