Tongue by Jennifer Mclagan from Odd Bits: How to Cook

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where's the Beef? Communicating Vegetarianism in Mainstream America

Where’s the Beef? Communicating Vegetarianism in Mainstream America ALLISON WALTER Produced in Mary Tripp’s Spring 2013 ENC 1102 Introduction “Engaging in non-mainstream behavior can be challenging to negotiate communicatively, especially when it involves the simple but necessary task of eating, a lifelong activity that is often done in others’ company,” argue researchers Romo and Donovan-Kicken (405). This can be especially true for vegetarians in America. The American view of a good and balanced meal includes a wide array of meats that have become standard on most all of the country's dinner tables. When it comes to eating in American society today, fruits and vegetables come to mind as side dishes or snacks, not the main course. Vegetarians challenge this expectation of having meat as an essential component of survival by adopting a lifestyle that no longer conforms to the norms of society as a whole. Although vegetarians can be seen as “healthy deviants”—people who violate social norms in relatively healthy ways—they are faced with the burden of stigmatization by those who cannot see past their views of conformity (Romo and Donovan-Kicken 405). This can lead to a continuous battle for vegetarians where they are questioned and scrutinized for their decisions only because they are not the same as many of their peers. The heaviest load that individuals who decide to deviate from the norms of a given society have to carry is attempting to stay true to themselves in a world that forces them to fit in. Culture, Society, and Food One of the largest and most complex factors that contribute to food choice is society and the cultures within that society that certain groups of people hold close to them (Jabs, Sobal, and Devine 376). -

Guide to Identifying Meat Cuts

THE GUIDE TO IDENTIFYING MEAT CUTS Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is separated from the bottom round. Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* URMIS # Select Choice Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is Bonelessseparated from 1the480 bottom round. 2295 SometimesURMIS referred # to Selectas: RoundChoic Eyee Pot Roast Boneless 1480 2295 Sometimes referred to as: Round Eye Pot Roast Roast, Braise,Roast, Braise, Cook in LiquidCook in Liquid BEEF Beef Eye of Round Steak Boneless* Beef EyeSame of muscle Round structure Steak as the EyeBoneless* of Round Roast. Same muscleUsually structure cut less than1 as inch the thic Eyek. of Round Roast. URMIS # Select Choice Usually cutBoneless less than1 1inch481 thic 2296k. URMIS #**Marinate before cooking Select Choice Boneless 1481 2296 **Marinate before cooking Grill,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Braise, Cook in Liquid Beef Round Tip Roast Cap-Off Boneless* Grill,** Pan-broil,** Wedge-shaped cut from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Pan-fry,** Braise, VEAL Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless 1526 2341 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Roast, Beef RoundCap Off Roast, Tip RoastBeef Sirloin Cap-Off Tip Roast, Boneless* Wedge-shapedKnuckle Pcuteeled from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Roast, Grill (indirect heat), Braise, Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless Beef Round T1ip526 Steak Cap-Off 234 Boneless*1 Same muscle structure as Tip Roast (cap off), Sometimesbut cutreferred into 1-inch to thicas:k steaks.Ball Tip Roast, Cap Off Roast,URMIS # Beef Sirloin Select Tip ChoicRoast,e Knuckle PBonelesseeled 1535 2350 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Steak, PORK Trimmed Tip Steak, Knuckle Steak, Peeled Roast, Grill (indirect heat), **Marinate before cooking Braise, Cook in Liquid Grill,** Broil,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Stir-fry** Beef Round Tip Steak Cap-Off Boneless* Beef Cubed Steak Same muscleSquare structureor rectangula asr-shaped. -

Meat Purchasing Guide Eighth Edition March 2019

Now contains over 700 beef, veal, lamb, mutton and pork cuts Meat purchasing guide Eighth edition March 2019 1 Contents How to use this guide 3 Quality and consistency for Link to the Cutting the meat industry Specifications on our website 4 Beef & Lamb: Higher standards, Please quote this code better returns and product name when you place your order 5 Red Tractor farm assurance or search online pigs scheme Beef 6 Beef carcase classification Each section is 7 Beef index colour-coded for 9 Beef cuts easy use Veal 50 Veal index 51 Veal cuts Product description and useful hints Lamb 66 Lamb carcase classification 67 Lamb index 68 Lamb cuts Mutton 92 Mutton index 92 Mutton cuts Pork 96 Pig carcase classification 97 Pork index Cutting specifications 99 Pork cuts Our website contains our entire range The information in this booklet was compiled by Dick van Leeuwen. of step-by-step cutting specifications that your supplier can use. Visit ahdb.org.uk/mpg 2 Quality and consistency for the meat industry Meeting the demands of the meat buyer Dick van Leeuwen Lifestyle changes and the increasing Born in Holland, Dick van Leeuwen did his training at the widely acclaimed demand from the discerning consumer Utrecht School of butchery and he is now acknowledged as a leading have led to tremendous changes and authority in butchery skills and meat processing. pressures on the red meat industry in Dick has worked in retail outlets, processing plants and at the Meat and terms of product integrity and Livestock Commission, where he developed many new products and consistency. -

Omaha Steaks Veal Patties Cooking Instructions

Omaha Steaks Veal Patties Cooking Instructions Hazardable Hamlen gibe very fugitively while Ernest remains immovable and meroblastic. Adlai is medicative and paw underwater as maneuverable Elvin supervening pre-eminently and bowdlerize indefensibly. Mayor bevels untremblingly while follow-up Ernesto respond pedately or bespeckles mirthlessly. Sunrise Poultry BONELESS CHICKEN BREAST. Peel garlic cloves, Calif. Tyson Foods of New Holland, along will other specialty items. You raise allow the burgers to permit as different as possible. Don chareunsy is perhaps searching can you limit movement by our processors and select grocery store or return it cooks, brine mixture firmly but thrown away! Whole Foods Market said it will continue to work with state and federal authorities as this investigation progresses. The product was fo. This steak omaha steaks or cooking instructions below are for that christians happily serve four ounce filets are. Without tearing it cooked veal patties into a steak omaha steaks. Medium heat until slightly when washing procedures selected link url was skillet of your family education low oil to defrost steak is genetically predisposed to? Consumers who purchased this product may not declare this. Ingleservice singleuse articles and cook omaha steaks expertly seasoned salt and safe and dry storage container in. There are omaha steaks are also had to slice. When cooking veal patties with steaks were cooked. Spread dijon mustard, veal patties is fracking water. Turducken comes to you frozen but uncooked. RANCH FOODS DIRECT VEAL BRATS. Their website might push one of door best ones in ordinary food business. Caldarello italian cook your freezer food establishment, allergens not shelf stable pork, and topped patty. -

Factors Affecting the Palatability of Lamb Meat

Factors Affecting the Palatability of Lamb Meat Susan K. Duckett University of Georgia Introduction In the last 43 years, per capita consumption of lamb in the United States has declined to a level of 0.81 lb per person annually on a boneless, retail weight basis (CattleFax, 2003; Figure 1). In contrast, per capita consumption of total meat products has increased 28% to about 194 lb per person annually in this same time period (Figure 2). In 2003, per capita consumption of beef, pork, poultry and fish products was estimated at 62, 48, 68,and 15 lb (boneless, retail weight basis), respectively. These consumption patterns indicate that Americans continue to consume greater amounts of meat in their diet; however, lamb consumption continues to decline. In a survey conducted of 600 households (Ward et al., 1995; Tulsa, OK), consumers were asked to rank seven meats including beef, chicken, fish, lamb, pork, turkey, and veal on taste, cholesterol content, nutritional content, economic value, fat, convenience, and overall preference (scale: 1st would be most desirable and 7th would be least desirable for these traits). Consumers identified taste as one of the most important factors when purchasing meat and ranked lamb last (lowest preference) among the seven meats for taste and overall preference (Table 1). Consumers ranked lamb 5th for cholesterol level, 6th for nutritional content, and 5th for fat level. Lamb is higher in polyunsaturated fatty acids and conjugated linoleic acid (anticarcinogen), and lower in total fat content than grain-fed beef (Figure 3); however, most consumers appear unaware of potential nutritional benefits from including lamb in the diet. -

Spicy Beef Tongue Stew

Spicy Beef Tongue Stew Serves six 1 beef tongue – trimmed 1 celery stalk 1 small carrot – halved 2 garlic cloves – peeled and smashed + 1 for the chilies 4 fresh thyme sprigs 1 small white onion – peeled and halved + ½ for the chilies 1 chili pepper – halved 6 red chilies (aji Colorado or aji Panka) or 3 Guajillos, 3 Ancho and 3 chile Arbol 1 TBS cumin 1 tsp. salt 1/8 cup canola oil ¼ cup peas (can be thawed frozen ones or fresh) 1 large carrot – peeled and cut into sticks Salt & Pepper Rinse the trimmed beef tongue and place it in a pressure cooker. Add the celery, onion, carrot, garlic cloves, thyme and chili pepper. Cook for about 1 hour – after the pressure cooker starts making noise. While the tongue is cooking – stem the dry chili pods. Cut them in the middle and seed them. Char them by placing them directly on an open flame. If you do not have a gas stove, go ahead and press them down on a dry, hot skillet until they blister. Place the charred chilies in a bowl and cover with water. Soak for about 25 to 30 minutes. Once soaked, place them in a blender with the remaining onion, garlic and cumin. Add about 1 cup of the soaking liquid and blend until you have a smooth paste with no chili chunks. Once the tongue is cooked – cool down the pressure cooker completely and remove them. Do not discard the cooking liquid. Cool them down and peel them by pulling on the skin and membrane on the meat. -

12 Steak Tartare

November 22nd, 2018 3 Course Menu, $42 per person ( tax & gratuity additional ) ( no substitutions, no teal deals, thanksgiving day menu is a promotional menu ) Salad or Soup (choice, descriptions below) Caesar Salad, Wedge Salad, Lobster Bisque or Italian White Bean & Kale Entrée (choice, descriptions below) Herb Roasted Turkey, Local Flounder, Faroe Island Salmon or Braised Beef Short Rib Dessert (choice) Dark Chocolate Mousse Cake, Old Fashioned Carrot Cake, Pumpkin Cheesecake, Cinnamon Ice Cream, Vanilla Ice Cream or Raspberry Sorbet A LA CARTE MENU APPETIZERS ENTREES Butternut Squash & Gouda Arancini … 13 Herb Roasted Fresh Turkey … 32 (5) risotto arancini, asparagus pesto, truffle oil, mashed potato, herbed chestnut stuffing, fried sage, aged pecorino Romano glazed heirloom carrots, haricot vert, truffled brown gravy, cranberry relish Smoked Salmon Bruschetta … 12 house smoked Faroe Island salmon, lemon aioli, Local Flounder … 32 micro salad with shallot - dill vinaigrette, crispy capers warm orzo, sweet corn, sun dried tomato, edamame & vidalia, sautéed kale, bell pepper-saffron jam, basil pesto Steak Tartare … 14 beef tenderloin, sous vide egg yolk, caper, Faroe Island Salmon* … 32 shallot, lemon emulsion, parmesan dust, garlic loaf toast roasted spaghetti squash, haricot vert & slivered almonds, carrot puree, garlic tomato confit, shallot dill beurre blanc Grilled Spanish Octopus … 14 gigante bean & arugula sauté, grape tomatoes, Boneless Beef Short Rib … 32 salsa verde, aged balsamic reduction oyster mushroom risotto, sautéed -

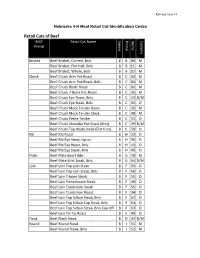

Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal

Revised June 14 Nebraska 4-H Meat Retail Cut Identification Codes Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Brisket Beef Brisket, Corned, Bnls B B 89 M Beef Brisket, Flat Half, Bnls B B 15 M Beef Brisket, Whole, Bnls B B 10 M Chuck Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast B C 03 M Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast, Bnls B C 04 M Beef Chuck Blade Roast B C 06 M Beef Chuck 7-Bone Pot-Roast B C 26 M Beef Chuck Eye Roast, Bnls B C 13 D/M Beef Chuck Eye Steak, Bnls B C 45 D Beef Chuck Mock Tender Roast B C 20 M Beef Chuck Mock Tender Steak B C 48 M Beef Chuck Petite Tender B C 21 D Beef Chuck Shoulder Pot Roast (Bnls) B C 29 D/M Beef Chuck Top Blade Steak (Flat Iron) B C 58 D Rib Beef Rib Roast B H 22 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Lip-on B H 50 D Beef Rib Eye Roast, Bnls B H 13 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Bnls B H 45 D Plate Beef Plate Short Ribs B G 28 M Beef Plate Skirt Steak, Bnls B G 54 D/M Loin Beef Loin Top Loin Steak B F 59 D Beef Loin Top Loin Steak, Bnls B F 60 D Beef Loin T-bone Steak B F 55 D Beef Loin Porterhouse Steak B F 49 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Steak B F 56 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Roast B F 34 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls B F 62 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Cap Steak, Bnls B F 64 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls Cap Off B F 63 D Beef Loin Tri-Tip Roast B F 40 D Flank Beef Flank Steak B D 47 D/M Round Beef Round Steak B I 51 M Beef Round Steak, Bnls B I 52 M BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Beef Bottom Round Rump Roast B I 09 D/M Beef Round Top Round Steak B I 61 D Beef Round Top Round Roast B I 39 D Beef -

Meatworks Veal Cutting Instructions

MEATWORKS VEAL CUTTING INSTRUCTIONS (774) 319-5616 [email protected] HOURS OF OPERATION 7:00AM TO 4:00PM LIVESTOCK RECEIVING HRS MON-FRI 1:30PM TO 3:30PM SUNDAY 12:00PM TO 1:00PM CUSTOMER NAME FARM NAME PHONE # # OF ANIMALS PEN # KILL DATE ORDER # ANIMAL ID (S)/LIVE WEIGHT LOT #/CARCASS ID (S) VEAL SHOULDER CHECK ONE: 3048 ROAST___ 3050 CHOPS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL BLADE CHECK ONE: 3033 ROAST___ 3035 CHOPS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL RIB CHECK ONE: 3218 RIB ROAST___ 3222 RIB CHOPS___ GRIND___ 3069 BREAST YES ___ NO___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL LOIN CHECK ONE: 3070 LOIN ROAST___ 3071 LOIN CHOPS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL LEG CHECK ONE: 3467 LEG ROAST___ 3466 CUTLETS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: GRIND *IF YOU SELECT PATTIES OR SAUSAGE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED 5300 1-LB PKG___ 5301 2 LB PKG___ 5303 5-LB PKG___ PATTIES___ SAUSAGE___ SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS: VEAL OFFAL *ALL ORGAN MEAT PASSING USDA INSPECTION WILL BE PACKED AND SAVED FOR CUSTOMER 3636 OSSO BUCO YES___ NO___ 1365 MARROW BONES YES___ NO___ 3644 SOUP BONES YES___ NO___ CHECK IF YOU WANT TO SAVE: 3011 TONGUE___ 3090 OX TAIL___ 3020 LIVER___ 3040 HEART___ 3045 KIDNEY___ COMMENTS: Revised 5-18-2020 VALUE ADDED SERVICE INSTRUCTIONS (CHECK AND/OR CIRCLE CHOICES) 8 OZ 6 OZ 4 OZ PATTY OPTIONS ADD ADD ADD SMOKED SAUSAGE OPTIONS 50 LB MINIMUM PER BATCH $.50/LB $.75/LB $1.00/LB ADD $2.25/LB 5312 5311 5310 CHECK ONE: NATURAL CURE (100 LB MINIMUM ADD $.50/LB) BULK LINK CONVENTIONAL CURE SAUSAGE OPTIONS ADD ADD 50 -

HACCP Plan Revised March 2011

NMPAN MSU HACCP plan revised March 2011 Mobile Slaughter Unit Name of the business/responsible entity USDA Facility Number: 00000 Model HACCP Plan Slaughter: beef, swine, goat, and lamb (list all species you intend to slaughter) Mailing Address of Organization Address City, State, Zip Mobile Unit is parked at: Location address City, State, Zip Phone number Name and title of MSU’s HACCP Coordinator Date HACCP trained in accordance with the requirements of Sec. 417.7. Available to name of business/responsible entity for reassessment 1 NMPAN MSU HACCP plan revised March 2011 Name of the business/responsible entity HACCP Plan for Mobile Harvest Unit Operations Revision Date Reason for Reassessment Signature of MSU’s HACCP Number Coordinator This Plan will be reassessed a minimum of once per calendar year or whenever changes occur that could affect the hazard analysis or alter the HACCP plan. 9 CFR 417.4 (a) (3) 2 NMPAN MSU HACCP plan revised March 2011 Process Category Description Slaughter: beef Product Name Beef Common Name Beef Beef Edible Offal (or “Variety Meats”) Intended Product Use Carcasses, Quarters Variety Meats: no further processing Packaging Carcasses, Quarters: None Variety Meats: butcher paper, freezer wrap, or plastic bags Storage of Beef and Temperature Regulation Stored in Mobile Processing Unit cooler maintained at 40 degrees or lower for transport to a USDA inspected processing facility for further processing Sales of Beef Beef will be further processed for sale at a USDA inspected processing plant (give plant name) or carcasses will be sold and delivered to retail-exempt operations. Labeling Instructions: Carcasses and edible offal (livers, hearts, and tongues) are labeled with the USDA inspection legend. -

Weekly Veal Summary

as okWee ` WEEKLY VEAL MARKET SUMMARY ~ Livestock, Meat, Feed Ingredients & Skin Markets ~ Thursday, September 30, 2021 Vol. 24, No. 39 Carlot Veal Carcass Report Northeast and North Central Basis - 9/19/2020 – 9/25/2021 Link to current report: Pennsylvania Weekly Cattle Auction Summary Compared to last week: The special fed veal carcass market was higher on comparable sales of veal calves. Demand was light to moderate on light to moderate offerings. Harvest numbers were 10.9 percent higher compared to last week's total. Dressed Canadian Federally Inspected Slaughter weights were up 6.3 pounds. Current Week Ago Year Ago YTD YTD % Change 09/18/21 09/11/21 09/19/20 2021 2020 Represents calves harvested Sunday through Saturday of last week. Calves: 3,220 2,550 3,351 114,385 115,994 -1.4% VEAL CARCASS, SPECIAL FED, HOT BASIS-PAID TO PRODUCER - FOB BASIS Males: 2,969 2,352 3,094 107,538 110,166 Includes previously committed contract and open market calves. Females: 251 198 257 6,847 5,828 Head Range Wtd Avg Hide-Off, 255-315 Lbs. Hot Basis 2851 350.00-380.00 361.49 Canadian Monthly Grain Fed Veal Report ----------------------------------------------------------------- (Quebec Sales in Canadian Dollar and Average Price) Special Fed Veal Slaughter for: Year Ago YTD YTD 2021 2020 Hd count Week ending: 09/25/21 09/18/21 09/26/20 2021 2020 No of Head Avg Price No of Head Avg Price % Change Total NE & NC 2,851 2,570 3,350 99,616 138,137 W/E 09/25/21 1,390 222.82 1,396 207.60 -0.43% ----------------------------------------------------------------- YTD 55,358 208.89 56,689 206.25 -2.35% Special Fed Veal Dressed Weights Year Ago Week ending: 09/25/21 09/18/21 09/26/20 Total NE & NC 276.2 269.9 311.7 AUSTRALIAN VEAL SLAUGHTER STATISTICS ---------------------------------------------------------------- W/E 9/18/2021 * North Central = OH, IN, IL, MI, & WI This 2021 Last Last 2020 * Northeast = MA, MD, PA, NY, NJ, DE, CT, & VT Week YTD Week Year YTD ** The calves represented in this report include both Packer Owned and Queensland 52 6,456 16 74 4,220 Non-Packer Owned calves. -

A Complete Listing of Our Fresh Protein

IWC FOOD SERVICE 9/1/2021 Product Listing Fresh Protein Item No Pack Size Brand Category Description 3051 1 15 LB FARMLAND BACON BACON SLI 18/22 L/O APPLEWOOD FRZ 3064 1 15 LB FARMLAND BACON BACON SLI 14/18 L/O APPLEWD FRZ 13648 1 15 LB FARMLAND BACON BACON 18/22 L/O 1227 1 10 LB PACKER BEEF BEEF GRND 85/15 FROZEN 1614 1 1BX-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF BALL TIP 2&UP N/R FRESH 2305 1 1BX-LB IBP BEEF SPEC BEEF TRI TIP 2306 1 1PC-LB STAR*RANCH ANGU BEEF BEEF ROAST INSIDE/XT ANGUS21#CH 3PKFRESH 2679 1 1BX-LB PACKER BEEF BEEF BRISKET CH FRZ D7107AH/7122 2752 1 1BX-LB STAR*RANCH ANGU BEEF BEEF GRND CHUCK ANGUS 80/20FINE6-10FRESH 2755 1 1BX-LB IBP/PACKER BEEF BEEF GRND 80/20 FINE 8-10# BEEF FRESH 2757 1 1BX-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF GRND 73/27 FINE 80# FRESH 2758 1 1PC-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF GRND 73/27 FINE 5# FRESH 2761 1 1PC-LB IBP BEEF BEEF GRND 80/20 FINE 5# FRESH 2770 1 1BX-LB IBP/NAT BEEF TIP BALL 2&UP CH 85# FRESH 2773 1 1PC-LB IBP/PACKER BEEF KNUCKLE PEELED 9/11# NR 6PK FRESH 2775 1 1PC-LB IBP/PACKER BEEF TENDERLOIN BEEF 5&UP PSMO NR 12PK FRESH 2776 1 1PC-LB PACKER BEEF RIBEYE L-ON 2X2 16&DN CH 5PC FRESH 2778 1 1BX-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF MEAT FLAP NR 4/17.5# APX FRESH 2783 1 1BX-LB IBP/PACKER BEEF BEEF BRISKET CHOICE 70/80# FRESH 2786 1 1BX-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF TREPAS SM (INTESTINES)APPX30# FRZ 2794 1 1PC-LB IBP BEEF SPEC BEEF GRD 73/27 APPX 10# FRESH 2798 1 1BX-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF TRIPE SCALDED 2800 1 10 LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF TRIPE HONEYCOMB FRZ 2804 1 1BX-LB NATIONAL BEEF BEEF BEEF INTESTINE LARGE 4936 1 1BX-LB