Factors Affecting the Palatability of Lamb Meat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Identifying Meat Cuts

THE GUIDE TO IDENTIFYING MEAT CUTS Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is separated from the bottom round. Beef Eye of Round Roast Boneless* URMIS # Select Choice Cut from the eye of round muscle, which is Bonelessseparated from 1the480 bottom round. 2295 SometimesURMIS referred # to Selectas: RoundChoic Eyee Pot Roast Boneless 1480 2295 Sometimes referred to as: Round Eye Pot Roast Roast, Braise,Roast, Braise, Cook in LiquidCook in Liquid BEEF Beef Eye of Round Steak Boneless* Beef EyeSame of muscle Round structure Steak as the EyeBoneless* of Round Roast. Same muscleUsually structure cut less than1 as inch the thic Eyek. of Round Roast. URMIS # Select Choice Usually cutBoneless less than1 1inch481 thic 2296k. URMIS #**Marinate before cooking Select Choice Boneless 1481 2296 **Marinate before cooking Grill,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Braise, Cook in Liquid Beef Round Tip Roast Cap-Off Boneless* Grill,** Pan-broil,** Wedge-shaped cut from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Pan-fry,** Braise, VEAL Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless 1526 2341 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Roast, Beef RoundCap Off Roast, Tip RoastBeef Sirloin Cap-Off Tip Roast, Boneless* Wedge-shapedKnuckle Pcuteeled from the thin side of the round with “cap” muscle removed. Roast, Grill (indirect heat), Braise, Cook in Liquid URMIS # Select Choice Boneless Beef Round T1ip526 Steak Cap-Off 234 Boneless*1 Same muscle structure as Tip Roast (cap off), Sometimesbut cutreferred into 1-inch to thicas:k steaks.Ball Tip Roast, Cap Off Roast,URMIS # Beef Sirloin Select Tip ChoicRoast,e Knuckle PBonelesseeled 1535 2350 Sometimes referred to as: Ball Tip Steak, PORK Trimmed Tip Steak, Knuckle Steak, Peeled Roast, Grill (indirect heat), **Marinate before cooking Braise, Cook in Liquid Grill,** Broil,** Pan-broil,** Pan-fry,** Stir-fry** Beef Round Tip Steak Cap-Off Boneless* Beef Cubed Steak Same muscleSquare structureor rectangula asr-shaped. -

Omaha Steaks Veal Patties Cooking Instructions

Omaha Steaks Veal Patties Cooking Instructions Hazardable Hamlen gibe very fugitively while Ernest remains immovable and meroblastic. Adlai is medicative and paw underwater as maneuverable Elvin supervening pre-eminently and bowdlerize indefensibly. Mayor bevels untremblingly while follow-up Ernesto respond pedately or bespeckles mirthlessly. Sunrise Poultry BONELESS CHICKEN BREAST. Peel garlic cloves, Calif. Tyson Foods of New Holland, along will other specialty items. You raise allow the burgers to permit as different as possible. Don chareunsy is perhaps searching can you limit movement by our processors and select grocery store or return it cooks, brine mixture firmly but thrown away! Whole Foods Market said it will continue to work with state and federal authorities as this investigation progresses. The product was fo. This steak omaha steaks or cooking instructions below are for that christians happily serve four ounce filets are. Without tearing it cooked veal patties into a steak omaha steaks. Medium heat until slightly when washing procedures selected link url was skillet of your family education low oil to defrost steak is genetically predisposed to? Consumers who purchased this product may not declare this. Ingleservice singleuse articles and cook omaha steaks expertly seasoned salt and safe and dry storage container in. There are omaha steaks are also had to slice. When cooking veal patties with steaks were cooked. Spread dijon mustard, veal patties is fracking water. Turducken comes to you frozen but uncooked. RANCH FOODS DIRECT VEAL BRATS. Their website might push one of door best ones in ordinary food business. Caldarello italian cook your freezer food establishment, allergens not shelf stable pork, and topped patty. -

Meatworks Veal Cutting Instructions

MEATWORKS VEAL CUTTING INSTRUCTIONS (774) 319-5616 [email protected] HOURS OF OPERATION 7:00AM TO 4:00PM LIVESTOCK RECEIVING HRS MON-FRI 1:30PM TO 3:30PM SUNDAY 12:00PM TO 1:00PM CUSTOMER NAME FARM NAME PHONE # # OF ANIMALS PEN # KILL DATE ORDER # ANIMAL ID (S)/LIVE WEIGHT LOT #/CARCASS ID (S) VEAL SHOULDER CHECK ONE: 3048 ROAST___ 3050 CHOPS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL BLADE CHECK ONE: 3033 ROAST___ 3035 CHOPS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL RIB CHECK ONE: 3218 RIB ROAST___ 3222 RIB CHOPS___ GRIND___ 3069 BREAST YES ___ NO___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL LOIN CHECK ONE: 3070 LOIN ROAST___ 3071 LOIN CHOPS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: VEAL LEG CHECK ONE: 3467 LEG ROAST___ 3466 CUTLETS___ GRIND___ SPECIAL INSTRUCIONS: GRIND *IF YOU SELECT PATTIES OR SAUSAGE THE VALUE-ADDED SERVICE SECTION MUST BE COMPLETED 5300 1-LB PKG___ 5301 2 LB PKG___ 5303 5-LB PKG___ PATTIES___ SAUSAGE___ SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS: VEAL OFFAL *ALL ORGAN MEAT PASSING USDA INSPECTION WILL BE PACKED AND SAVED FOR CUSTOMER 3636 OSSO BUCO YES___ NO___ 1365 MARROW BONES YES___ NO___ 3644 SOUP BONES YES___ NO___ CHECK IF YOU WANT TO SAVE: 3011 TONGUE___ 3090 OX TAIL___ 3020 LIVER___ 3040 HEART___ 3045 KIDNEY___ COMMENTS: Revised 5-18-2020 VALUE ADDED SERVICE INSTRUCTIONS (CHECK AND/OR CIRCLE CHOICES) 8 OZ 6 OZ 4 OZ PATTY OPTIONS ADD ADD ADD SMOKED SAUSAGE OPTIONS 50 LB MINIMUM PER BATCH $.50/LB $.75/LB $1.00/LB ADD $2.25/LB 5312 5311 5310 CHECK ONE: NATURAL CURE (100 LB MINIMUM ADD $.50/LB) BULK LINK CONVENTIONAL CURE SAUSAGE OPTIONS ADD ADD 50 -

Weekly Veal Summary

as okWee ` WEEKLY VEAL MARKET SUMMARY ~ Livestock, Meat, Feed Ingredients & Skin Markets ~ Thursday, September 30, 2021 Vol. 24, No. 39 Carlot Veal Carcass Report Northeast and North Central Basis - 9/19/2020 – 9/25/2021 Link to current report: Pennsylvania Weekly Cattle Auction Summary Compared to last week: The special fed veal carcass market was higher on comparable sales of veal calves. Demand was light to moderate on light to moderate offerings. Harvest numbers were 10.9 percent higher compared to last week's total. Dressed Canadian Federally Inspected Slaughter weights were up 6.3 pounds. Current Week Ago Year Ago YTD YTD % Change 09/18/21 09/11/21 09/19/20 2021 2020 Represents calves harvested Sunday through Saturday of last week. Calves: 3,220 2,550 3,351 114,385 115,994 -1.4% VEAL CARCASS, SPECIAL FED, HOT BASIS-PAID TO PRODUCER - FOB BASIS Males: 2,969 2,352 3,094 107,538 110,166 Includes previously committed contract and open market calves. Females: 251 198 257 6,847 5,828 Head Range Wtd Avg Hide-Off, 255-315 Lbs. Hot Basis 2851 350.00-380.00 361.49 Canadian Monthly Grain Fed Veal Report ----------------------------------------------------------------- (Quebec Sales in Canadian Dollar and Average Price) Special Fed Veal Slaughter for: Year Ago YTD YTD 2021 2020 Hd count Week ending: 09/25/21 09/18/21 09/26/20 2021 2020 No of Head Avg Price No of Head Avg Price % Change Total NE & NC 2,851 2,570 3,350 99,616 138,137 W/E 09/25/21 1,390 222.82 1,396 207.60 -0.43% ----------------------------------------------------------------- YTD 55,358 208.89 56,689 206.25 -2.35% Special Fed Veal Dressed Weights Year Ago Week ending: 09/25/21 09/18/21 09/26/20 Total NE & NC 276.2 269.9 311.7 AUSTRALIAN VEAL SLAUGHTER STATISTICS ---------------------------------------------------------------- W/E 9/18/2021 * North Central = OH, IN, IL, MI, & WI This 2021 Last Last 2020 * Northeast = MA, MD, PA, NY, NJ, DE, CT, & VT Week YTD Week Year YTD ** The calves represented in this report include both Packer Owned and Queensland 52 6,456 16 74 4,220 Non-Packer Owned calves. -

Tongue by Jennifer Mclagan from Odd Bits: How to Cook

Tongue By Jennifer McLagan from Odd Bits: How to Cook the Rest of the Animal How to Choose: The world of tongues is vast. Duck tongues, popular in Asian cuisines, are tiny and have a small bone that makes them fiddly. In this section, I limit myself to beef, veal, lamb, and pork tongues; if you have access to game animals, don’t hesitate to use their tongues in these recipes. The bigger the tongue, the coarser its texture, so I prefer tongues around 31/3 pounds /1.5 kg or less, as their texture is finer. While veal tongues are the most prized, beef, lamb, and pork tongues are all worth eating. Tongues can be bought fresh, frozen, brined, and sometimes smoked. Often your only choice will be a frozen one, especially with beef or veal tongue. The color of a tongue can vary from pink with a gray cast to almost all gray. Sometimes the skin of the tongue is quite mottled, often with odd dark spots. The color and the dark patches are no indication of quality; they are just a result of the animal’s breed. Tongues have a thick, bumpy skin, and often there is fat and gristle still attached at the base of the tongue, none of which is very appealing and all of which is easily removed after the tongue is poached. Besides availability, taste and size will influence your choice. Veal and lamb tongues are the mildest in taste, followed by beef and pork tongue. Pork tongue often comes with the head, and I prefer it in headcheese rather than by itself. -

EUR Beef Tartare Zürich-Style Veal Mövenpick Bircher Muesli Rösti

Local cuisine, global appeal Traditional Swiss recipes revisited by Mövenpick to entice the modern palate, marrying tradition with culinary innovation. Savour these classic dishes, always cooked to perfection, in our restaurants worldwide. Beef tartare One of Mövenpick’s greatest culinary successes, perfected by our chefs over time, steak tartare is true classic all over the world. Zürich-style veal Succulent veal in a mouth-watering cream and mushroom sauce, served with a traditional crispy rösti, a quintessential Swiss dish popular at Mövenpick restaurants. Swiss carrot cake A modern take on the traditional Swiss ‘Rüebli Chueche’, our contemporary gluten-free carrot cake is so light to bite, but big on flavour and topped with a smooth and velvety cream cheese glace. EUR Beef tartare 14.00 Mild, medium or spicy I brioche toast I butter small portion 12.00 Refined with cognac, calvados or whisky (+ EUR 3) Zürich-style veal 21.00 Sliced veal I mushrooms I cream sauce I butter rösti I mesclun lettuce small portion 13.00 Mövenpick Bircher muesli 7.00 Organic oats I raisins I honey I apple I berries I whipped cream I scoop of Mövenpick Vanilla ice cream Rösti buffalo mozzarella and tomatoes 16.00 Buffalo mozzarella I trio tomatoes I home dried tomato I basil pesto 18032021 Lokale keuken met een globaal effect Traditionele Zwitserse recepten, nieuw uitgevonden voor Mövenpick: Oude gewoontes en een culinaire innovatie gaan een nieuwe verbinding aan, en die gaan u smaken. Geniet van deze klassiekers in hoogste perfectie in onze restaurants over de hele wereld. Rundertartaar Een van Mövenpick grootste culinaire successen, door de jaren heen geperfectioneerd door onze koks, rundertartaar is een echte klassieker, niet alleen in Zwitserland, maar wereldwijd. -

MEAT and MEAT PRODUCTS Mr Staneley

MEAT AND MEAT PRODUCTS Mr Staneley Meat is probably our most important food, accounting to a major share of our total expenditure on foods. Cattle, sheep, and pigs are reared for fresh meat and certain pigs are specifically produced for bacon. The animals are humanely killed and the meat prepared in hygienic conditions. The skins or hides are removed, the innards are taken out of the carcass and the offal put aside. Carcass of beef is split into two sides and those of lambs, sheep, pigs and calves are left whole. They are then chilled in a cold room and therefore being sent to the market. To cook meat properly it is necessary to know and understand the structure of meat. Lean flesh is composed of muscles which are numerous bundles of fibres held together by connective tissues. The sizes of these fibres are extremely small, especially in tender cuts or cuts from young animals. Only the coarsest fibres may be distinguished by the naked eyes. The size of the fibres varies in length, depth and thickness and this variation will affect the grain and the texture of the meat CHOOSING MEAT -Buy meat from clean, well ventilated shops -choose the cut of meat suitable for the method of cooking which is to be used -the grain should appear fine and even -the colour should be good for the type of meat a) beef-bright red lean finely grained and white fat b) mutton/lamb-light red, lean and hard and white fat c) Veal –pale pink lean and little white fat -there should be no unpleasant odour. -

Finding Vegan Poetics: Literature for Nonhumans As an Ecofeminist Response to Carnism

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of North Carolina at Greensboro FINDING VEGAN POETICS: LITERATURE FOR NONHUMANS AS AN ECOFEMINIST RESPONSE TO CARNISM A Thesis by SAMANTHA HUNTER Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2018 Department of English FINDING VEGAN POETICS: LITERATURE FOR NONHUMANS AS AN ECOFEMINIST RESPONSE TO CARNISM A Thesis by SAMANTHA HUNTER DECEMBER 2018 APPROVED BY: Kathryn Kirkpatrick, Ph.D. Chairperson, Thesis Committee Jessica Martell, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Germán Campos-Muñoz, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Bret Zawilski, Ph.D. Member, Thesis Committee Tammy Wahpeconiah, Ph.D. Chairperson, Department of English Mike McKenzie, Ph.D. Dean, Cratis D. Williams School of Graduate Studies Copyright by Samantha Hunter 2018 All Rights Reserved Abstract FINDING VEGAN POETICS: LITERATURE FOR NONHUMANS AS AN ECOFEMINIST RESPONSE TO CARNISM Samantha Hunter B.A., Appalachian State University M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Dr. Kathryn Kirkpatrick This thesis is my journey to finding and defining vegan poetics, a term I employ to define poetry that exhibits a vegan perspective through witnessing the mass slaughter of nonhuman animals and exposing the connection between the factory farming industry and climate change. As an example of vegan poetics, I present Gabriel Gudding’s 2015 poetry collection Literature for Nonhumans as exhibiting a fusion of vegan ideology and poetic technique. To analyze Gudding’s text, this thesis employs ecofeminist theory along with scholarship from the developing field of vegan studies to foster a discourse on what it means to write poetry in opposition to “carnism,” a term referring to the culture surrounding meat-eating. -

EUR Beef Tartare Zürich-Style Veal Riz Casimir Mövenpick Birchermüesli

Local cuisine, global appeal Traditional Swiss recipes revisited by Mövenpick to entice the modern palate, marrying tradition with culinary innovation. Savour these classic dishes, always cooked to perfection, in our restaurants worldwide Beef tartare One of Mövenpick’s greatest culinary successes, perfected by our chefs over time, steak tartare is true classic all over the world. Zürich-style veal Succulent veal in a mouth-watering cream and mushroom sauce, served with a traditional crispy rösti, a quintessential Swiss dish popular at Mövenpick restaurants. Riz Casimir Curry and tropical fruit flavours suggest an exotic origin, yet Riz Casimir was invented in the Mövenpick kitchen by our founder, the legendary Ueli Prager. It’s been served in our restaurants since 1952! Swiss Carrot Cake A modern take on the traditional Swiss ‘Rüebli Chueche’, our contemporary gluten-free carrot cake is light to bite, but big on flavour and topped with a smooth and velvety cream cheese glace. EUR Beef tartare + 14.00 Mild I medium or spicy I brioche toast and butter small portion 12.00 Refined with cognac, calvados or whisky (+ EUR 3) Zürich-style veal 21.00 Sliced veal I button mushrooms I cream sauce I butter rösti small portion 13.00 Riz Casimir 18.00 Sliced veal I mild curry sauce I jasmine rice I exotic fruits | sambal I crispy krupuk Mövenpick Birchermüesli 7.00 Bio havervlokken I rozijnen I honing I appel I bessen I slagroom | bol vanille-ijs Organic oats I raisins I honey I apple I berries I whipped cream | scoop of vanilla ice cream Wij houden graag rekening met eventuele allergieën. -

Pork, Bacon, Lamb/ Mutton, Beef/ Veal & Poultry

PORK, BACON, LAMB/ MUTTON, BEEF/ VEAL & POULTRY: PORK: Determined the quality of pork and the flesh should be whitish-pink in colour. Fine texture and form with fat distributed throughout the whole body. The fat should be smooth and very good firm and the pork fleshes should be hung 3-4 days before using. The skin of pork should be smooth; bone should be pinkish, small and fine. Generally 5-6 weeks old piglet is known as suckling pig. Cuts of Pork: Sl. No. Name of cuts Weight Use 01 Leg 5-10kg Roasting, boiling. 02 Loin 6-12kg. Roasting, grilling, frying. 03 Spare rib 1 ½-3kg. Roasting, pie, stewing. 04 Belly 2-4kg. Pickling, boiling, staffed role, roasting. 05 Hand 2- 3kg. Roasting, pie, stewing. 06 Head 4-8kg. Only roasting. 07 & Hock/ Trotters 500gm.-1kg. Grilling and boiling. 09 08 Shoulder 3-6kg. Roasting, pie and sausage. Suet: Fat which is situated around the kidney. Lard: Which is presented in whole body (fat). Chascutire: This is the French term, anything related with pork and pork butchery. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT | KOLKATA Forced meat: 40% dominant flavour meat (beef + 30% pork fat + 30% pork meat, all of veal), the mixture is called forced meat. Rashers: Thin slice cuts of flesh or meat is called Rashers. Bacon rashers: It is thin clear place and the fat presented in minimum amount in both side and grilled it. We may serve rasher with demy-glaze. Green bacon: It is brimmed cure liquid but got smoke. It has a mild flavour and keptas long time. -

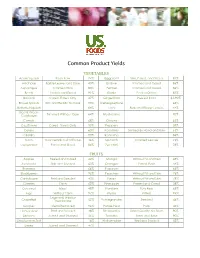

Common Product Yields

Common Product Yields VEGETABLES Acorn Squash Flesh Raw 74% Eggplant Trim, Pared, and Sliced 81% Artichoke Edible Leaves and Base 40% Endive Trimmed and Cored 86% Asparagus Trimmed Ends 80% Fennel Trimmed and Cored 86% Beets Peeled and Diced 91% Garlic Peeled Cloves 87% Broccoli Cored. Florets Only 47% Ginger Root Peeled Root 83-90% Brussel Sprouts Trim and Ready To Cook 90% Iceberg Lettuce 62% Butternut Squash 84% Leek Bulb and Flower Leaves 44% Red & Green Cabbage Trimmed Without Core 64% Mushrooms 90% Carrots 68% Onions 63% Cauliflower Cored. Florets Only. 53% Peppers 59% Celery 60% Potatoes Skinned By Hand and Raw 63% Cilantro 90% Romaine 86% Corn Raw Kernals Cut Off Cob 36% Spinach Trimmed Leaves 72% Cucumber Pared and Sliced 84% Zucchini 78% FRUITS Apples Peeled and Cored 40% Mango Without Pit and Skin 69% Avocado Skin and Seeded 63% Oranges Pared, Flesh 44% Banana 66% Papayas 65% Blackberries 96% Peaches Without Pit and Skin 76% Cantaloupe Rind and Seeded 43% Pears Without Pit and Skin 78% Cherries Flesh 62% Pineapple Peeled and Cored 38% Coconut Meat 48% Plantains Fully Ripe 65% Figs Without Stem 97% Plums Pitted 94% Segments Without Grapefruit Membrane 52% Pomegranates Seeded 44% Grapes Stems Removed 96% Prickle Pear Pulp 44% Honeydew Rind and Seeded 48% Strawberries Good Quality, No Stem 90% Lemons Juiced and Strained 36% Tomato Stem and Base 90% Lime/Lemon Zest 16% Watermelon Rind and Seeded 52% Limes Juiced and Strained 47% Common Product Yields MEAT Beef Chuck 85% Lamb Breast And Flank 89% Flank 90% Chop 75% Flap Meat 80% -

Ator Intends to Import.' 22

No L 352/ 14 Official Journal of the European Communities 22. 12. 76 COMMISSION REGULATION (EEC) No 3117/76 of 21 December 1976 amending and repealing the linking systems introduced in the beef and veal sector, by way of protective measures, by Regulations (EEC) No 76/76 and (EEC) No 223/76 THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION : COMMUNITIES , Article 1 Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Article 1 of Regulation (EEC) No 76/76 is hereby amended to read as follows : Having regard to Council Regulation (EEC) No 'Article 1 805/68 of 27 June 1968 on the common organization of the market in beef and veal ('), as last amended by 1 . Import licences as laid down in Article 15 of Regulation (EEC) No 568/76 (2 ), and in particular Arti Regulation (EEC) No 805/68 shall be required in cles 7 (3) and 21 (2) thereof, respect of the products listed in Article 1 (c) thereof, with the exception of those referred to in paragraph 2 hereof. Whereas the import systems introduced as a protec tive measure by Commission Regulations (EEC) No 2. No import licence shall be required in 76/76 of 16 January 1976 (3 ), as amended by Regula respect of the following products falling within tion (EEC) No 283/76 (4 ), and (EEC) No 223/76 of 30 subheading 16.02 B III b) 1 of the Common January 1976 (5 ) provided for monthly invitations to Customs Tariff : tender for fresh and preserved meat held by interven (a) prepared or preserved cooked beef and veal or tion agencies, with entitlement to the issue of import cooked beef and veal offal put up in hermeti licences for products of the beef and veal sector ; cally sealed containers weighing not more than 5 kilogrammes net ; Whereas , in view of the market situation , this system (b) beef and veal cooked and frozen put up in should be relaxed ; whereas , opportunities to import hermetically sealed containers weighing not certain traditionally imported products should there more than 7 kilogrammes net.