Where's the Beef? Communicating Vegetarianism in Mainstream America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spicy Beef Tongue Stew

Spicy Beef Tongue Stew Serves six 1 beef tongue – trimmed 1 celery stalk 1 small carrot – halved 2 garlic cloves – peeled and smashed + 1 for the chilies 4 fresh thyme sprigs 1 small white onion – peeled and halved + ½ for the chilies 1 chili pepper – halved 6 red chilies (aji Colorado or aji Panka) or 3 Guajillos, 3 Ancho and 3 chile Arbol 1 TBS cumin 1 tsp. salt 1/8 cup canola oil ¼ cup peas (can be thawed frozen ones or fresh) 1 large carrot – peeled and cut into sticks Salt & Pepper Rinse the trimmed beef tongue and place it in a pressure cooker. Add the celery, onion, carrot, garlic cloves, thyme and chili pepper. Cook for about 1 hour – after the pressure cooker starts making noise. While the tongue is cooking – stem the dry chili pods. Cut them in the middle and seed them. Char them by placing them directly on an open flame. If you do not have a gas stove, go ahead and press them down on a dry, hot skillet until they blister. Place the charred chilies in a bowl and cover with water. Soak for about 25 to 30 minutes. Once soaked, place them in a blender with the remaining onion, garlic and cumin. Add about 1 cup of the soaking liquid and blend until you have a smooth paste with no chili chunks. Once the tongue is cooked – cool down the pressure cooker completely and remove them. Do not discard the cooking liquid. Cool them down and peel them by pulling on the skin and membrane on the meat. -

12 Steak Tartare

November 22nd, 2018 3 Course Menu, $42 per person ( tax & gratuity additional ) ( no substitutions, no teal deals, thanksgiving day menu is a promotional menu ) Salad or Soup (choice, descriptions below) Caesar Salad, Wedge Salad, Lobster Bisque or Italian White Bean & Kale Entrée (choice, descriptions below) Herb Roasted Turkey, Local Flounder, Faroe Island Salmon or Braised Beef Short Rib Dessert (choice) Dark Chocolate Mousse Cake, Old Fashioned Carrot Cake, Pumpkin Cheesecake, Cinnamon Ice Cream, Vanilla Ice Cream or Raspberry Sorbet A LA CARTE MENU APPETIZERS ENTREES Butternut Squash & Gouda Arancini … 13 Herb Roasted Fresh Turkey … 32 (5) risotto arancini, asparagus pesto, truffle oil, mashed potato, herbed chestnut stuffing, fried sage, aged pecorino Romano glazed heirloom carrots, haricot vert, truffled brown gravy, cranberry relish Smoked Salmon Bruschetta … 12 house smoked Faroe Island salmon, lemon aioli, Local Flounder … 32 micro salad with shallot - dill vinaigrette, crispy capers warm orzo, sweet corn, sun dried tomato, edamame & vidalia, sautéed kale, bell pepper-saffron jam, basil pesto Steak Tartare … 14 beef tenderloin, sous vide egg yolk, caper, Faroe Island Salmon* … 32 shallot, lemon emulsion, parmesan dust, garlic loaf toast roasted spaghetti squash, haricot vert & slivered almonds, carrot puree, garlic tomato confit, shallot dill beurre blanc Grilled Spanish Octopus … 14 gigante bean & arugula sauté, grape tomatoes, Boneless Beef Short Rib … 32 salsa verde, aged balsamic reduction oyster mushroom risotto, sautéed -

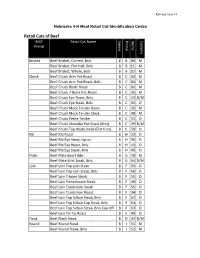

Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal

Revised June 14 Nebraska 4-H Meat Retail Cut Identification Codes Retail Cuts of Beef BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Brisket Beef Brisket, Corned, Bnls B B 89 M Beef Brisket, Flat Half, Bnls B B 15 M Beef Brisket, Whole, Bnls B B 10 M Chuck Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast B C 03 M Beef Chuck Arm Pot-Roast, Bnls B C 04 M Beef Chuck Blade Roast B C 06 M Beef Chuck 7-Bone Pot-Roast B C 26 M Beef Chuck Eye Roast, Bnls B C 13 D/M Beef Chuck Eye Steak, Bnls B C 45 D Beef Chuck Mock Tender Roast B C 20 M Beef Chuck Mock Tender Steak B C 48 M Beef Chuck Petite Tender B C 21 D Beef Chuck Shoulder Pot Roast (Bnls) B C 29 D/M Beef Chuck Top Blade Steak (Flat Iron) B C 58 D Rib Beef Rib Roast B H 22 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Lip-on B H 50 D Beef Rib Eye Roast, Bnls B H 13 D Beef Rib Eye Steak, Bnls B H 45 D Plate Beef Plate Short Ribs B G 28 M Beef Plate Skirt Steak, Bnls B G 54 D/M Loin Beef Loin Top Loin Steak B F 59 D Beef Loin Top Loin Steak, Bnls B F 60 D Beef Loin T-bone Steak B F 55 D Beef Loin Porterhouse Steak B F 49 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Steak B F 56 D Beef Loin Tenderloin Roast B F 34 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls B F 62 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Cap Steak, Bnls B F 64 D Beef Loin Top Sirloin Steak, Bnls Cap Off B F 63 D Beef Loin Tri-Tip Roast B F 40 D Flank Beef Flank Steak B D 47 D/M Round Beef Round Steak B I 51 M Beef Round Steak, Bnls B I 52 M BEEF Retail Cut Name Specie Primal Name Cookery Primal Beef Bottom Round Rump Roast B I 09 D/M Beef Round Top Round Steak B I 61 D Beef Round Top Round Roast B I 39 D Beef -

HOW MUCH MEAT to EXPECT from a BEEF CARCASS Rob Holland, Director Center for Profitable Agriculture

PB 1822 HOW MUCH MEAT TO EXPECT FROM A BEEF CARCASS Rob Holland, Director Center for Profitable Agriculture Dwight Loveday, Associate Professor Department of Food Science and Technology Kevin Ferguson UT Extension Area Specialist-Farm Management University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture CONTENTS 2...Introduction 3...Dressing Percentage 5...Chilled Carcass and Primal Cuts 6...Sub-primal Meat Cuts 6...Factors Affecting Yield of Retail Cuts 7...Average Amount of Meat from Each Sub-primal Cut 9...Summary University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture Introduction Consumers who buy a live animal from a local cattle producer for custom processing are often surprised. Some are surprised at the quantity of meat and amount of freezer space they need. Others may be surprised that they did not get the entire live weight of the animal in meat cuts. The amount of meat actually available from a beef animal is a frequent source of misunderstanding between consumers, processors and cattle producers. This document provides information to assist in the understanding of how much meat to expect from a beef carcass. The information provided here should be helpful to consumers who purchase a live animal for freezer beef and to cattle producers involved in direct and retail meat marketing. 2 University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture How Much Meat to Expect from a Beef Carcass Dressing Percentage One of the terms used in the cattle and meat cutting industry that often leads to misunderstanding is dressing percentage. The dressing percentage is the portion of the live animal weight that results in the hot carcass. -

Beef Breakdown.Indd

Your Beef Breakdown, Explained If you have ever purchased a quarter, a side or a whole 14- to 21-day period. During this aging process the meat Loin and Round, all possess di erent beef carcass, chances are you have wondered why you have develops avor, and most importantly, becomes more taste characteristics because they are received less meat than expected. e average weight of a tender. Unfortunately, a small amount of weight is lost made up of di erent muscles with live steer or heifer ready for harvest is 1,300 pounds! So during the aging process due to water evaporation. di erent tenderness levels, di erent how much of this product should you expect to receive in Carcass to Cuts fat contents and varying avor pro les. edible meat products? For instance, the Chuck and Round After the carcass is properly aged, it is ready to be are most commonly seen in roast Steer to Carcass broken down into retail cuts. On average, 21 percent of form, but Round Roasts are much In order to change a 1,300-pound beef animal into edible each carcass is inedible bone, fat and connective tissue. leaner (have less fat) than those from meat product, butchers rst have to convert it into a Once the carcass is fabricated and inedible objects are the Chuck and therefore will have a carcass by removing the hide, head and internal organs. removed, a whole carcass will yield about 639 pounds of less intense avor. e Rib and Loin On average, only 62 percent of the animal’s original edible beef product. -

Tongue by Jennifer Mclagan from Odd Bits: How to Cook

Tongue By Jennifer McLagan from Odd Bits: How to Cook the Rest of the Animal How to Choose: The world of tongues is vast. Duck tongues, popular in Asian cuisines, are tiny and have a small bone that makes them fiddly. In this section, I limit myself to beef, veal, lamb, and pork tongues; if you have access to game animals, don’t hesitate to use their tongues in these recipes. The bigger the tongue, the coarser its texture, so I prefer tongues around 31/3 pounds /1.5 kg or less, as their texture is finer. While veal tongues are the most prized, beef, lamb, and pork tongues are all worth eating. Tongues can be bought fresh, frozen, brined, and sometimes smoked. Often your only choice will be a frozen one, especially with beef or veal tongue. The color of a tongue can vary from pink with a gray cast to almost all gray. Sometimes the skin of the tongue is quite mottled, often with odd dark spots. The color and the dark patches are no indication of quality; they are just a result of the animal’s breed. Tongues have a thick, bumpy skin, and often there is fat and gristle still attached at the base of the tongue, none of which is very appealing and all of which is easily removed after the tongue is poached. Besides availability, taste and size will influence your choice. Veal and lamb tongues are the mildest in taste, followed by beef and pork tongue. Pork tongue often comes with the head, and I prefer it in headcheese rather than by itself. -

A Qualitative Study of Vegan-Omnivore Conflict Kelly Guerin University of Colorado Boulder

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by CU Scholar Institutional Repository University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar Undergraduate Honors Theses Honors Program Spring 2014 Where's the Beef? (With Vegans): A Qualitative Study of Vegan-Omnivore Conflict Kelly Guerin University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/honr_theses Recommended Citation Guerin, Kelly, "Where's the Beef? (With Vegans): A Qualitative Study of Vegan-Omnivore Conflict" (2014). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 109. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Honors Program at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Guerin 1 Where’s the Beef? (With Vegans): A Qualitative Study of Vegan-Omnivore Conflict Kelly Guerin Anthropology Departmental Honors Thesis University of Colorado at Boulder Defended April 4th, 2014 Thesis Advisor Dr. Darna Dufour, Department of Anthropology Defense Committee Dr. Abby Hickcox, Honors Program Dr. Steven Leigh, Department of Anthropology Approved by IRB on November 17th, 2013 Guerin 2 Introduction In 2010, the United Nations Environment Programme issued a groundbreaking environmental impact report focusing on the causes, rather than effects, of environmental degradation and stressed that agriculture be moved into the spotlight as a main contributor to the rapid depletion of resources. It was cited that agriculture accounts for 70% of the earth’s freshwater, 38% of total land use, 19% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Shockingly, half of the crops produced were directed to the raising of livestock (UNEP report, 2010). -

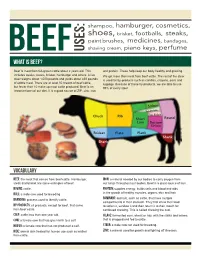

What Is BEEF?

shampoo, hamburger, cosmetics, shoes, brisket, footballs, steaks, paint brushes, medicines, bandages, shaving cream, piano keys, BEEF USES: perfume What is BEEF? Beef is meat from full-grown cattle about 2 years old. This and protein. These help keep our body healthy and growing. includes steaks, roasts, brisket, hamburger and others. A live We get more than meat from beef cattle. The rest of the steer steer weighs about 1,000 pounds and yields about 450 pounds is used for by-products such as candles, crayons, paint and of edible meat. There are at least 50 breeds of beef cattle, luggage. Because of these by-products, we are able to use but fewer than 10 make up most cattle produced. Beef is an 99% of every steer. important part of our diet. It is a good source of ZIP: zinc, iron Sirloin Tenderloin Chuck Rib Top Sirloin Short Round Loin Bottom Sirloin Brisket Plate Flank Shank Shank VOCABULARY Beef: the meat that comes from beef cattle. Hamburger, Iron: a mineral needed by our bodies to carry oxygen from steak and brisket are some examples of beef. our lungs throughout our bodies. Beef is a great source of iron. Bovine: cattle. Protein: supplies energy, builds cells and blood and aids in the growth of healthy muscles, organs, skin and hair. Bull: a male cow used for breeding. Ruminant: animals, such as cattle, that have multiple Branding: process used to identify cattle. compartments in their stomach. They first chew their food By-Products: all products, except for beef, that come to soften it, swallow it and then return it to their mouth for from beef cattle. -

Corned Beef Cooking Instructions

Corned Beef Cooking Instructions Traditional Cooking: 3 1/2 Hours Remove the brisket from the marinade and rinse it thoroughly. Place it in a large stock pot and add just enough water to cover it and throw in a carrot, an onion and a stalk of celery. Cover the pot and turn the heat on high until it comes to a boil and then reduce the heat to low. Simmer the beef for at least three hours or until the meat is soft and tender when poked with a fork. Drain and slice thinly. Pressure Cooking: 1 Hour Place a rinsed corned beef brisket into the steaming basket of your pressure cooker. Sprinkle it with a little garlic salt and add 2 cups of water to the bottom of the pot. Secure the lid, shutting it firmly and place the pressure relief valve on top. Turn the heat on medium or until the pressure reading stays around 15 pounds of pressure. Cook the beef for an hour. Cool it down, open the lid and add potatoes, carrots and cabbage and close. Bring the pressure back up for 5 minutes to cook the vegetables and then cool again. Oven Method: 4 Hours Heat your oven to 300 degrees F. Rinse the corned beef and place in a shallow baking dish. Add enough water to cover the bottom of the pan with about 1/2 inch of water. Cover the pan with foil and place in the oven to bake for about 4 hours. Remove the meat from the pan and drain the juices into a saucepan. -

“Dine In” with Beef & Veal, Family-Friendly Recipes

Kaitlyn Carey “DINE IN” WITH BEEF & VEAL, Director of Consumer Affairs - FAMILY-FRIENDLY RECIPES THE BEEF CHECKOFF PROGRAM Non-profit organization Working on behalf of Pennsylvania’s 25,100 beef, dairy and veal producers Work in cooperation with the National Beef Checkoff Program Mission Statement: Be a unified voice for our beef & veal partners by sharing their legacy of commitment with the families enjoying dinner with us. TODAY’S GOALS Overview of the Beef & Veal Resources available to you and your students Beef It’s What’s for Dinner Website Veal Made Easy Website Veal Farm Website Beef & Veal in the Classroom Grant Program Beef & Veal in the Classroom Toolkit Virtual Farm Tour Opportunity Recipe Demonstration – Ground Beef & Pasta Skillet Primavera Q&A BEEF RESOURCES Beef Recipes Beef Cooking Lessons Beef Cuts Education Beef Nutrition Information & Education Meet the Beef Community Beef Supply Chain Resources One integrated website - www.beefitswhatsfordinner.com Veal Recipes Veal Cooking Lessons Veal Cut Information Veal Nutrition Information www.vealmadeeasy.com VEAL RESOURCES How Today’s Veal is Raised Animal Care Food Safety Veal Quality Assurance www.vealfarm.com VEAL RESOURCES DISCOVERING FARMLAND Lesson Plans and Curriculum designed to support the Farmland Film We highly recommend showing the Farmland Film as part of your protein lesson TRUE BEEF Lesson Plans and Curriculum designed to support the True Beef Documentary We highly recommend showing the True Beef film as part of your protein lesson BEEF & VEAL IN THE CLASSROOM -

The History of Steak Tartare - a Knol by Richard Wottrich 4/6/12 9:08 AM

The History of Steak Tartare - a knol by Richard Wottrich 4/6/12 9:08 AM The History of Steak Tartare Steak Tartare Recipes From Around the World Many people are not attuned to the art of eating raw meat. Others find the practice to be abhorrent. But in my view consuming raw meat tugs at hard wired yearnings deep within our Homo sapiens’ collective soul... Contents The key seasonings is allspice (which the Lebanese call sweet pepper), along with salt, pepper and, sometimes, cinnamon, cumin or even a little hot... Abstract of Meeting Paper: Society for Risk Analysis 2001 Annual Meeting !"#$%&"'&&("&$)*(+",)&$-")$.)$.&"/0."$)"1&$,)"23"4&$.,5"$(6"#$%&"71&$.14"1*%&6")0")&11"0/"*)8"9,"$"40:(+,)&."*(")#&"9;&.*7$("<*6=&,)5 077$,*0($114"0("$">$):.6$4";4"/$)#&."=0:16"'.*(+"#0;&"/.&,#".4&"'.&$6"$(6"$"?0:(6"0/"+.0:(6".0:(6",)&$-"/.0;"0:."107$1"':)7#&.8"@:) =0:16"70;&"$("016"=006&("'0=1"$(6"*("*)"6$6"=0:16";*A")#&",)&$-5"$".$="&++"401-5"7$?&.,5"7#0??&6"$(7#0%*&,5"$"6$'"0/"#0)";:,)$.6"$(6 7#0??&6"0(*0(,8"B$6"=0:16",?.&$6"*)")#*7-14"0("$",1$'"0/".4&"'.&$65"$66",$1)"$(6"?&??&.5"0?&("$"7016"'&&.5"$(6")#&("$"100-"0/",$)*,/$7)*0( =0:16"$??&$.":?0("#*,"/$7&"1*-&"(0"0)#&.8 C?0("):.(*(+",&%&()&&("!"$..*%&6"*("D.&;&(5"E&,)"F&.;$(45"*(")#&",:;;&."GHIJ"$,"$("9;&.*7$("K*&16">&.%*7&"LM9K>MN"#*+#",7#001 &A7#$(+&",):6&()5"$(6"0(&"0/")#&"/*.,)")#*(+,"!".&;&;'&.",&&*(+"=&.&",$(6=*7#"-*0,-,"6*,?1$4*(+",)&$-")$.)$.&8"O#&".$=";&$)"=$,"0:) )#&.&".*+#)"*(")#&",:(5"*(")#&"0?&(8"!",$=5"!"$)&5"$(6"!",:.%*%&68 P0=&%&.5":?0(".&):.(*(+")0"9;&.*7$"!"#$%&"0%&.")#&"4&$.,"&(70:()&.&6"*((:;&.$'1&",)$.&,5"70;;&(),"$(6"Q:*?,"0%&.";4"?&.7#$(7&"/0. -

How Much Meat?

The information in this OKLAHOMA DEPT. OF AGRICULTURE, brochure represents an FOOD, & FORESTRY average. The actual live weight to retail cuts yield varies, and is dependent on various factors such How Much as breed, fat to muscle ratio, cutting order, age, Meat? etc. Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food, & For- estry offers its programs to Food Safety Division all eligible persons regard- Meat Inspection Services less of race, color, national Food Safety Division origin, religion, sex, age, or handicap and is an Equal Meat Inspection Services Opportunity Employer Phone: 405-522-6119 Fax: 405-522-1060 Visit us at: http://www.oda.state.ok.us Tel: 405-522-6119 1,000 lb. Steer 610 lbs. Beef 430 lbs. Retail Cuts (on the hoof) (on the rail) (cut & wrapped, bring home) • Round 103.2 lbs. Round Steak Rump Roast Sirloin Tip Steak 1,000 lb. Round 24% Pikes Peak Roast Cubed Steaks Stew Beef & Ground Beef • Sirloin 38.7 lbs Sirloin Steak Stew Beef & Ground Beef Sirloin 9% • Short Loin 34.4 lbs. Porterhouse Steak Not all of the cow makes it to the T-Bone Steak table. On average, a 1,000 pound Stew Beef & Ground Beef steer will only weigh approximately Flank • Flank 17.2 lbs. 61% of it’s live weight once it makes Short Loin 4% Flank Steak 8% Short Ribs it to the rail. This approximate 39% Ground Beef loss during the slaughter and dress- • Rib 38.7 lbs. ing procedure is a result of the ani- Rib Eye Steak mal being bled and the hide, head, Rib Steaks Back Ribs hooves, viscera, lungs and heart be- Rib Short Stew Beef & Ground Beef ing removed.