The Past, Present, and Future of Petroleum Development in Mexico, Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil Refining in Mexico and Prospects for the Energy Reform

Articles Oil refining in Mexico and prospects for the Energy Reform Daniel Romo1 1National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract: This paper analyzes the conditions facing the oil refining industry in Mexico and the factors that shaped its overhaul in the context of the 2013 Energy Reform. To do so, the paper examines the main challenges that refining companies must tackle to stay in the market, evaluating the specific cases of the United States and Canada. Similarly, it offers a diagnosis of refining in Mexico, identifying its principal determinants in order to, finally, analyze its prospects, considering the role of private initiatives in the open market, as well as Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), as a placeholder in those areas where private enterprises do not participate. Key Words: Oil, refining, Energy Reform, global market, energy consumption, investment Date received: February 26, 2016 Date accepted: July 11, 2016 INTRODUCTION At the end of 2013, the refining market was one of stark contrasts. On the one hand, the supply of heavy products in the domestic market proved adequate, with excessive volumes of fuel oil. On the other, the gas and diesel oil demand could not be met with production by Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex). The possibility to expand the infrastructure was jeopardized, as the new refinery project in Tula, Hidalgo was put on hold and the plan was made to retrofit the units in Tula, Salamanca, and Salina Cruz. This situation constrained Pemex's supply capacity in subsequent years and made the country reliant on imports to supply the domestic market. -

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report

Climate and Energy Benchmark in Oil and Gas Insights Report Partners XxxxContents Introduction 3 Five key findings 5 Key finding 1: Staying within 1.5°C means companies must 6 keep oil and gas in the ground Key finding 2: Smoke and mirrors: companies are deflecting 8 attention from their inaction and ineffective climate strategies Key finding 3: Greatest contributors to climate change show 11 limited recognition of emissions responsibility through targets and planning Key finding 4: Empty promises: companies’ capital 12 expenditure in low-carbon technologies not nearly enough Key finding 5:National oil companies: big emissions, 16 little transparency, virtually no accountability Ranking 19 Module Summaries 25 Module 1: Targets 25 Module 2: Material Investment 28 Module 3: Intangible Investment 31 Module 4: Sold Products 32 Module 5: Management 34 Module 6: Supplier Engagement 37 Module 7: Client Engagement 39 Module 8: Policy Engagement 41 Module 9: Business Model 43 CLIMATE AND ENERGY BENCHMARK IN OIL AND GAS - INSIGHTS REPORT 2 Introduction Our world needs a major decarbonisation and energy transformation to WBA’s Climate and Energy Benchmark measures and ranks the world’s prevent the climate crisis we’re facing and meet the Paris Agreement goal 100 most influential oil and gas companies on their low-carbon transition. of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Without urgent climate action, we will The Oil and Gas Benchmark is the first comprehensive assessment experience more extreme weather events, rising sea levels and immense of companies in the oil and gas sector using the International Energy negative impacts on ecosystems. -

Integrating Into Our Strategy

INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY • 03 MAY 2017 Integrating Climate Into Our Strategy INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY • 03 CONTENTS Foreword by Patrick Pouyanné, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Total 05 Three Questions for Patricia Barbizet, Lead Independent Director of Total 09 _____________ SHAPING TOMORROW’S ENERGY Interview with Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency 11 The 2°C Objective: Challenges Ahead for Every Form of Energy 12 Carbon Pricing, the Key to Achieving the 2°C Scenario 14 Interview with Erik Solheim, Executive Director of UN Environment 15 Oil and Gas Companies Join Forces 16 Interview with Bill Gates, Breakthrough Energy Ventures 18 _____________ TAKING ACTION TODAY Integrating Climate into Our Strategy 20 An Ambition Consistent with the 2°C Scenario 22 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Down 23% Since 2010 23 Natural Gas, the Key Energy Resource for Fast Climate Action 24 Switching to Natural Gas from Coal for Power Generation 26 Investigating and Strictly Limiting Methane Emissions 27 Providing Affordable Natural Gas 28 CCUS, Critical to Carbon Neutrality 29 A Resilient Portfolio 30 Low-Carbon Businesses to Become the Responsible Energy Major 32 Acquisitions That Exemplify Our Low-Carbon Strategy 33 Accelerating the Solar Energy Transition 34 Affordable, Reliable and Clean Energy 35 Saft, Offering Industrial Solutions to the Climate Change Challenge 36 The La Mède Biorefinery, a Responsible Transformation 37 Energy Efficiency: Optimizing Energy Consumption 38 _____________ FOCUS ON TRANSPORTATION Offering a Balanced Response to New Challenges 40 Our Initiatives 42 ______________ OUR FIGURES 45 04 • INTEGRATING CLIMATE INTO OUR STRATEGY Total at a Glance More than 98,109 4 million employees customers served in our at January 31, 2017 service stations each day after the sale of Atotech A Global Energy Leader No. -

South of the Border, Down Mexico Way: the Past, Present, and Future of Petroleum Development in Mexico,‡ Part I

Owen L. Anderson* & J. Jay Park† SOUTH OF THE BORDER, DOWN MEXICO WAY: THE PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF PETROLEUM DEVELOPMENT IN MEXICO,‡ PART I ABSTRACT Mexico is estimated to have 9.8 billion barrels of untapped oil reserves, or about 10 percent of the world’s crude oil; however, much remains undeveloped and production is declining as a result of dysfunction in the structure of Mexico’s petroleum regime. Until recently, Mexico’s Constitution and laws limited oil and gas activities to those of its state oil company, Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), which struggled to invest in new drilling and technology. In 2013, however, Mexico reopened its petroleum sector to foreign investment. Although 75 years in the making, Mexico is taking a bold new path toward developing its petroleum resources. Mexico stands to benefit from foreign investment and new technology to develop its remaining resources, which include shale deposits, deepwater reserves, and reserves only recoverable through modern enhanced recovery techniques. This two-part article has two objectives: Part I reviews the history of petroleum in Mexico—much of it unhappy—as a reminder of the long and tortuous pathway that led to Mexico’s current initiative to open its petroleum sector to foreign investment. The Mexican economy was built on oil in the early 1900s, but a combination of nationalism, petroleum-investor arrogance, and eventual over- dependence on petroleum revenues all served to undermine the Mexican oil industry. It is important for petroleum investors to understand and appreciate this history in order to ease the transition of new oil production in Mexico. -

Shell QRA Q2 2021

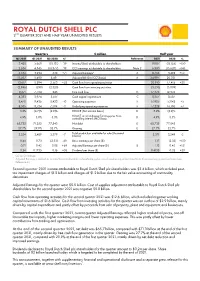

ROYAL DUTCH SHELL PLC 2ND QUARTER 2021 AND HALF YEAR UNAUDITED RESULTS SUMMARY OF UNAUDITED RESULTS Quarters $ million Half year Q2 2021 Q1 2021 Q2 2020 %¹ Reference 2021 2020 % 3,428 5,660 (18,131) -39 Income/(loss) attributable to shareholders 9,087 (18,155) +150 2,634 4,345 (18,377) -39 CCS earnings attributable to shareholders Note 2 6,980 (15,620) +145 5,534 3,234 638 +71 Adjusted Earnings² A 8,768 3,498 +151 13,507 11,490 8,491 Adjusted EBITDA (CCS basis) A 24,997 20,031 12,617 8,294 2,563 +52 Cash flow from operating activities 20,910 17,415 +20 (2,946) (590) (2,320) Cash flow from investing activities (3,535) (5,039) 9,671 7,704 243 Free cash flow G 17,375 12,376 4,383 3,974 3,617 Cash capital expenditure C 8,357 8,587 8,470 9,436 8,423 -10 Operating expenses F 17,905 17,042 +5 8,505 8,724 7,504 -3 Underlying operating expenses F 17,228 16,105 +7 3.2% (4.7)% (2.9)% ROACE (Net income basis) D 3.2% (2.9)% ROACE on an Adjusted Earnings plus Non- 4.9% 3.0% 5.3% controlling interest (NCI) basis D 4.9% 5.3% 65,735 71,252 77,843 Net debt E 65,735 77,843 27.7% 29.9% 32.7% Gearing E 27.7% 32.7% Total production available for sale (thousand 3,254 3,489 3,379 -7 boe/d) 3,371 3,549 -5 0.44 0.73 (2.33) -40 Basic earnings per share ($) 1.17 (2.33) +150 0.71 0.42 0.08 +69 Adjusted Earnings per share ($) B 1.13 0.45 +151 0.24 0.1735 0.16 +38 Dividend per share ($) 0.4135 0.32 +29 1. -

The Modernization of the EU-Mexico Global Agreement, 2000-2020

Master’s Degree in Comparative International Relations Final Thesis Towards a new generation trade agreement: the modernization of the EU-Mexico Global Agreement, 2000-2020 Supervisor Ch. Prof. Duccio BASOSI Assistant supervisor Ch. Prof. Vanni PETTINÀ Graduand Silvia SCHIAVONI 877176 Academic Year 2019/2020 Index Abstract 1 Introduction 5 Chapter 1: The external trade policy of the EU 1) Influences on the evolution of European trade policies 10 2) The Common Commercial Policy of the EU 13 3) The Treaty of Lisbon and the new EU trade strategies 20 4) Main characteristics of FTAs/PTAs 26 5) First Generation FTAs 31 6) DCFTA 35 7) EPA 36 8) New Generation Agreements 38 9) The new generation of EU FTAs: South Korea, Japan, Singapore, Vietnam, TTIP, CETA and Mercosur 41 Chapter 2: Mexico’s external policy and its trade relations with the EU 1) History of Mexican commercial policy 53 2) The 1980s trade opening and liberalization reforms 60 3) The North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) 64 4) European Union relations with Latin America 68 5) Evolution of Mexican relation with the European Union, 1900s – 1992 73 6) The framework of the 1997 Mexico-European Union Global Agreement negotiations 83 Chapter 3: Modernization of the Mexico-European Union Global Agreement 1) Analysis of the Global Agreement and the 2008 Strategic Partnership 88 2) First years of Global Agreement implementation: 2002-2006 97 3) EU-Mexico relations in the framework of the Global Agreement 2006-2012 106 4) The period 2012-2016 and the decision to modernize the Global Agreement 115 5) Global Agreement impact assessment 123 6) The Agreement in Principle and the inclusion of new elements 129 Conclusion 139 Bibliography 144 Abstract Verso la metà degli anni Novanta, mentre il Messico firmava l’Accordo nordamericano di libero commercio con i due partner principali dell’America del Nord, gli Stati Uniti e il Canada, la quota europea del mercato messicano diminuiva in maniera costante. -

Statoil Business Update

Statoil US Onshore Jefferies Global Energy Conference, November 2014 Torstein Hole, Senior Vice President US Onshore competitively positioned 2013 Eagle Ford Operator 2012 Marcellus Operator Williston Bakken 2011 Stamford Bakken Operator Marcellus 2010 Eagle Ford Austin Eagle Ford Houston 2008 Marcellus 1987 Oil trading, New York Statoil Office Statoil Asset 2 Premium portfolio in core plays Bakken • ~ 275 000 net acres, Light tight oil • Concentrated liquids drilling • Production ~ 55 kboepd Eagle Ford • ~ 60 000 net acres, Liquids rich • Liquids ramp-up • Production ~34 koepd Marcellus • ~ 600 000 net acres, Gas • Production ~130 kboepd 3 Shale revolution: just the end of the beginning • Entering mature phase – companies with sustainable, responsible development approach will be the winners • Statoil is taking long term view. Portfolio robust under current and forecast price assumptions. • Continuous, purposeful improvement is key − Technology/engineering − Constant attention to costs 4 Statoil taking operations to the next level • Ensuring our operating model is fit for Onshore Operations • Doing our part to maintain the company’s capex commitments • Leading the way to reduce flaring in Bakken • Not just reducing costs – increasing free cash flow 5 The application of technology Continuous focus on cost, Fast-track identification, Prioritised development of efficiency and optimisation of development & implementation of potential game-changing operations short-term technology upsides technologies SHORT TERM – MEDIUM – LONG TERM • Stage -

Pervasive Precarity: Migrant Mexican Oil Workers

Pervasive Precarity: Migrant Mexican Oil Workers’ Experiences and Tactics to Navigate Uncertainty By Rebecca J. Crosthwait © 2014 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson, Donald D. Stull, Ph.D., M.P.H. ________________________________ Brent E. Metz, Ph.D. ________________________________ Ebenezer Obadare, Ph.D. ________________________________ Peter Herlihy, Ph.D. ________________________________ Ruben Flores, Ph.D. Date Defended: November 24, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Rebecca J. Crosthwait certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Pervasive Precarity: Migrant Mexican Oil Workers’ Experiences and Tactics to Navigate Uncertainty ________________________________ Chairperson Donald D. Stull Date approved: December 10, 2014 ii Abstract An ethnographic analysis of precarity as experienced by migrant Mexican oil workers in permanently insecure work structures in the Gulf of Mexico, this study explores precarious employment situations in the oil industry and tactics workers use to navigate, cope with, and diminish uncertainty. In addition to workers’ experiences, I analyze the contexts in which individuals live and work, including: labor-market changes; the history, politics, and geography of oil; and hurricanes’ impacts on labor. To better understand the tightrope walk between precarious employment and unemployment, I conducted interviews with workers and others affiliated with the oil industry during fieldwork in the Coastal Bend of Texas, in 2008, and Ciudad del Carmen, Mexico, in 2012. Both areas are important in the Gulf of Mexico oil industry and draw workers for projects both in the fabrication of offshore vessels and drilling and production of offshore oil. -

Oil for As Long As Most Americans Can Remember, Gasoline Has Been the Only Fuel They Buy to Fill up the Cars They Drive

Fueling a Clean Transportation Future Chapter 2: Gasoline and Oil For as long as most Americans can remember, gasoline has been the only fuel they buy to fill up the cars they drive. However, hidden from view behind the pump, the sources of gasoline have been changing dramatically. Gasoline is produced from crude oil, and over the last two de- cades the sources of this crude have gotten increasingly di- verse, including materials that are as dissimilar as nail polish remover and window putty. These changes have brought rising global warming emissions, but not from car tailpipes. Indeed, tailpipe emissions per mile are falling as cars get more efficient. Rather, it is the extraction and refining of oil that are getting dirtier over time. The easiest-to-extract sources of oil are dwindling, and the oil industry has increasingly shifted its focus to resources that require more energy-intensive extraction or refining methods, resources that were previously too expensive and risky to be developed. These more challenging oils also result Yeulet © iStock.com/Cathy in higher emissions when used to produce gasoline (Gordon 2012). The most obvious way for the United States to reduce the problems caused by oil use is to steadily reduce oil con- sumption through improved efficiency and by shifting to cleaner fuels. But these strategies will take time to fully im- plement. In the meantime, the vast scale of ongoing oil use Heat-trapping emissions from producing transportation fuels such as gasoline are on the rise, particularly emissions released during extracting and refining means that increases in emissions from extracting and refin- processes that occur out of sight, before we even get in the car. -

Mexico's Deep Water Success

Energy Alert February 1, 2018 Key Points Round 2.4 exceeded expectations by awarding 18 of 29 (62 percent) of available contract areas Biggest winners were Royal Dutch Shell, with nine contract areas, and PC Carigali, with seven contract areas Investments over $100 billion in Mexico’s energy sector expected in the upcoming years Mexico’s Energy Industry Round 2.4: Mexico’s Deep Water Success On January 31, 2018, the Comisión Nacional de Hidrocarburos (“CNH”) completed the Presentation and Opening of Bid Proposals for the Fourth Tender of Round Two (“Round 2.4”), which was first announced on July 20, 2017. Round 2.4 attracted 29 oil and gas companies from around the world including Royal Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, Chevron, Pemex, Lukoil, Qatar Petroleum, Mitsui, Repsol, Statoil and Total, among others. Round 2.4 included 60% of all acreage to be offered by Mexico under the current Five Year Plan. Blocks included 29 deep water contract areas (shown in the adjacent map) with an estimated 4.23 billion Barrel of Oil Equivalent (BOE) of crude oil, wet gas and dry gas located in the Perdido Fold Belt Area, Salinas Basin and Mexican Ridges. The blocks were offered under a license contract, similar to the deep water form used by the CNH in Round 1.4. After witnessing the success that companies like ENI, Talos Energy, Inc., Sierra and Premier have had in Mexico over the last several years, Round 2.4 was the biggest opportunity yet for the industry. Some of these deep water contract areas were particularly appealing because they share geological characteristics with some of the projects in the U.S. -

The Future of Pemex: Return to the Rentier-State Model Or Strengthen Energy Resiliency in Mexico?

THE FUTURE OF PEMEX: RETURN TO THE RENTIER-STATE MODEL OR STRENGTHEN ENERGY RESILIENCY IN MEXICO? Isidro Morales, Ph.D. Nonresident Scholar, Center for the United States and Mexico, Baker Institute; Senior Professor and Researcher, Tecnológico de Monterrey March 2020 © 2020 by Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Baker Institute. Isidro Morales, Ph.D “The Future of Pemex: Return to the Rentier-State Model or Strengthen Energy Resiliency in Mexico?” https://doi.org/10.25613/y7qc-ga18 The Future of Pemex Introduction Mexico’s 2013-2014 energy reform not only opened all chains of the energy sector to private, national, and international stakeholders, but also set the stage for Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) to possibly become a state productive enterprise. We are barely beginning to discern the fruits and limits of the energy reform, and it will be precisely during Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s administration that these reforms will either be enhanced or curbed. Most analysts who have justified the reforms have highlighted the amount of private investment captured through the nine auctions held so far. Critics of the reform note the drop in crude oil production and the accelerated growth of natural gas imports and oil products. -

Mexico in the Time of COVID-19: an OPIS Primer on the Impact of the Virus Over the Country’S Fuel Market

Mexico in the Time of COVID-19: an OPIS Primer on the Impact of the Virus Over the Country’s Fuel Market Your guide to diminishing prices and fuel demand Mexico in the Time of COVID-19 Leading Author Daniel Rodriguez Table of Contents OPIS Contributors Coronavirus Clouds Mexico’s Energy Reform ................................................................1 Justin Schneewind Eric Wieser A Historic Demand Crash ....................................................................................................2 OPIS Editors IHS Markit: Worst Case Drops Mexico’s Gasoline Sales to 1990 levels ...................3 Lisa Street Bridget Hunsucker KCS: Mexico Fuel Demand to Drop Up to 50% .............................................................4 IHS Markit ONEXPO: Retail Sales Drop 60% ......................................................................................4 Contirbuitors Carlos Cardenas ONEXPO: A Retail View on COVID-19 Challenges..........................................................5 Debnil Chowdhury Felipe Perez IHS Markit: USGC Fuel Prices to Remain Depressed Into 2021 .................................6 Kent Williamson Dimensioning the Threat ....................................................................................................7 Paulina Gallardo Pedro Martinez Mexico Maps Timeline for Returning to Normality ......................................................7 OPIS Director, Tales of Two Quarantines ...................................................................................................8 Refined