Women's Cattle Ownership in Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Programme 2018

71st Saturday 26th May Heathfield & District 2018 8am – 5.15pm AGRICULTURAL SHOW Little Tottingworth Farm, ICUL GR TU A not-for-profit organisation benefiting the local community A R A Broad Oak, Heathfield, D L L S E I O East Sussex F C H I T E A T E Y H FREE THE SOUTH EAST’S PREMIER PROGRAMME ONE DAY AGRICULTURAL SHOW F R E E M A N F O RMA N CONTENTS 4 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION FORM 17 WOMEN’S INSTITUTE Experts in handling the sale of a wide range of superb properties from Apartments and Pretty Cottages up to exclusive Country Homes, Estates and Farms 6 TIMETABLE OF EVENTS 17 MICRO BREWERY FESTIVAL 8 SOCIETY OFFICIALS 26 VINTAGE TRACTOR & WORKING STEAM SOLD SOLD 9 STEWARDS 18 NEW ENTERPRISE ZONE 10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 20 COUNTRY WAYS 12 SPONSORS & DONATIONS 11 FARMERS MARKET 14 COMPETITIONS & ATTRACTIONS 22 ARTS & CRAFTS MARQUEE 27 TRADE STANDS 24 SUSSEX FEDERATION OF YOUNG FARMERS’ CLUB 33 CATTLE SECTION SOLD SOLD 50 SHOWGROUND MAP 24 EDUCATION AREA 53 SHEEP SECTION 24 PLUMPTON COLLEGE 48 PIG SECTION 16 DISPLAYS 61 HORSE SECTION LIABILITY TO THE PUBLIC AND/OR EXHIBITORS ® Country Homes Battle 01424 777165 Country Homes Tunbridge Wells 01892 615757 A) All visitors to premises being used by the Society accept that the Society its Officers, employees or Est 1982 May 2018 servants shall have taken all reasonable steps to ensure the safety of such visitors while in or upon Battle Burwash Hawkhurst Heathfield the premises, or while entering or leaving the same. B) All visitors to premises being used by the Society shall at all times exercise all reasonable care 01424 773888 01435 883800 01580 755320 01435 865055 while in or upon the premises, or while entering or leaving the same. -

Canada's Great Victorian-Era Exposition and Industrial Fair Toronto, August 30Th to September 11Th, 1897

w ^' :^^^mi^i^^ ^^Jk^ /^ wJCJjJ'^^jt^^M^MiS i| K^"^ f^v' ism WutM^i'^mms^ sWfi'" -^ ^^^W'''^ ; NStki%^'^^^^^^.^- 97' I sgraBKOs INDUSTRIAL; mM ^^'^^^:^^^^T^- S3' epti y^ ^^r«i The EDITH and LORNE PIERCE COLLECTION o/CANADIANA iiueeris University at Kingston \ BEST OF ALL BEST OF ALL ^V^KDA'S c G/?e, r Victorian-Era t^ t^ Jr* JF* J* ^* t^^ ^* ^^ ^^ j^ t^ t^ eiJ* 1^ ^^ e^*' e^^ t^^ ^^ fSr' «^*' t^ t^^ W* -« t^* e^*' e^* «^^ e^* f^ t^ «^ «^ «^ Exposition e(5* «^* e^* «^* e^* t^* e^* ^^ 9^* t^ e^* «^^ e^** e,^'' e^^ Industrial Fair ^-^jjs^ AUGUST 30th to SEPTEMBER I Ith, 1697 THE NATIONAL E2a'OSITION OF CANADA'S RESOURCES COMPETITION OPEN TO THE WORLD $55,000 in Premiums RULES AND REGULATIONS, Etc. EXTRA NEW SPECIAL ATTRACTIONS. THE CROWNING EVENT OF THE JUBILEE YEAR. EXHIBITION OFFICES: 82 KING ST. EAST, TORONTO THE MAIt JOB PRINT, TORONTO ^^^^^^^,^^^^^^^^^^^»f,f,f>»f,^,f>^,^,f>^,^^^^^^ o CL X LJ ^;-V^ *v^- •>' V *^ -^' I/\DE\ TO PRIZE LIST PAGE Officers and Directors 4 Rules and Regulations 5 to 12 Horse Department 13 to 22 Pony Exhibits 19. 20 Boy Riders 22 Speeding in the Ring 23 to 26 Notice of Auction Sale of Live fctock 27 Cattle 26 to 36 Sheep 35 to 43 Pigs 43 to 48 Poultry and Pigeons 48 to 61 Dairy Products and Utentils 61 to 64 Grains, Roots and Vegetables 64 to 67 Horticultural Department 68 to 75 Honey and Apiary Supplies 75 to 77 Minerals and Natural History 77 Implements 77, 78 Engines, Machinery, Pumps, etc 78, 79 Safes, Hardware, Gates and Fencing 80 Gas Fixtures, Metal Work and House Furnishings — 81 Leather, Boots and Shoes -

The Inconvenient Indigenous

1 SIDSEL SAUGESTAD The Inconvenient Indigenous Remote Area Development in Botswana, Donor Assistance, and the First People of the Kalahari The Nordic Africa Institute, 2001 2 The book is printed with support from the Norwegian Research Council. Front cover photo: Lokalane – one of the many small groups not recognised as a community in the official scheme of things Back cover photos from top: Irrigation – symbol of objectives and achievements of the RAD programme Children – always a hope for the future John Hardbattle – charismatic first leader of the First People of the Kalahari Ethno-tourism – old dance in new clothing Indexing terms Applied anthropology Bushmen Development programmes Ethnic relations Government policy Indigenous peoples Nation-building NORAD Botswana Kalahari San Photos: The author Language checking: Elaine Almén © The author and The Nordic Africa Institute 2001 ISBN 91-7106-475-3 Printed in Sweden by Centraltryckeriet Åke Svensson AB, Borås 2001 3 My home is in my heart it migrates with me What shall I say brother what shall I say sister They come and ask where is your home they come with papers and say this belongs to nobody this is government land everything belongs to the State What shall I say sister what shall I say brother […] All of this is my home and I carry it in my heart NILS ASLAK VALKEAPÄÄ Trekways of the Wind 1994 ∫ This conference that I see here is something very big. It can be the beginning of something big. I hope it is not the end of something big. ARON JOHANNES at the opening of the Regional San Conference in Gaborone, October 1993 4 Preface and Acknowledgements The title of this book is not a description of the indigenous people of Botswana, it is a characterisation of a prevailing attitude to this group. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

The Stoneleigh Herd

HERD FEATURE THE STONELEIGH HERD The Stoneleigh Herd of Sussex cattle was founded in 2002, a year after Debbie Dann and Alan Hunt had bought the RASE’s herd of rare breed White Park Cattle. White Parks, for all their good looks and photogenic charm, are not the most commercial of breeds so they wanted a breed to complement the White Parks and that would pay the bills and ensure the cattle weren’t just a glorified hobby. After looking at a number of native breeds the selection was narrowed down to South Devons and Sussex (Debbie is originally from Hersmonceux in East Sussex). Sussex easily trumped the South Devons! The dispersal of Mike Cushing’s Coombe Ash Herd in May 2002 provided the ideal opportunity to buy some foundation cows and four cows with calves at foot and back in calf again found themselves travelling up the M40 to Warwickshire. Coombe Ash Godinton 5th, bought as a calf at foot from the Coombe Ash dispersal sale and her heifer calf summer 2013 Debbie’s day job at that time was to run all the competitive classes for the Royal Show and Alan was and still is the Estate Manager for the Royal Showground’s farmland. Since 2007 Debbie has been Breed Secretary for the Longhorn Cattle Society. This means that both Alan and Debbie have full time jobs and the cattle are mostly managed outside of work hours and have to be pretty low maintenance. Stoneleigh Godinton 2nd and calf Cows are housed over the winter as all the grazing is rented and the cattle are easier to manage when they are indoors when the owners are working full time. -

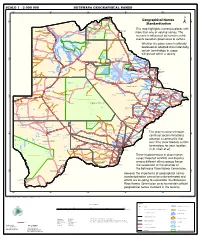

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

Modise ON.Pdf (1.579Mb)

A comparative analysis of the relationship between political party preference and one-party dominance in Botswana and South Africa ON Modise orcid.org 0000-0001-7883-9015 Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Social Science in International Relations at the North West University Supervisor: Dr N Sempijja Co-supervisor: Dr JO Maseng Graduation ceremony: July 2019 Student number: 224037 DECLARATION I declare that this dissertation is my original work and it has not been submitted anywhere in full or partially to any university for a degree. All contributions and sources cited here have been duly acknowledged through complete references. _____________________ Obakeng Naledi Modise July 2019 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “I was lucky to have been born in a family that knew the value of education, I was very fortunate to come from a family who gave me the opportunities and skills to succeed in life. Thereafter, I have had to work hard to be lucky” Khaya Dlanga This thesis has been at the epicenter of my life for the past two years. It has been the most challenging academic endeavor of my existence and has tested me in ways that I would have never known were possible. Throughout this journey my family cheered me on. To my mother, thank you for indulging me, for your support, love and prayers. This is for you. To my father, for keeping my wits intact, I appreciate your love and support. To my aunt, Dorcas Thai I am grateful for the words you continuously speak over my life. I cherish the love you continuously shower me with. -

The Discourse of Tribalism in Botswana's 2019 General Elections

The Discourse of Tribalism in Botswana’s 2019 General Elections Christian John Makgala ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5984-5153 Andy Chebanne ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5393-1771 Boga Thura Manatsha ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5573-7796 Leonard L. Sesa ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6406-5378 Abstract Botswana’s much touted peaceful Presidential succession experienced uncertainty after the transition on 1 April 2019 as a result of former President Ian Khama’s public fallout with his ‘handpicked’ successor, President Mokgweetsi Masisi. Khama spearheaded a robust campaign to dislodge Masisi and the long-time ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) from power. He actively assisted in the formation of a new political party, the Botswana Patriotic Front (BPF). Khama also mobilised the country’s most populous Central District, the Bangwato tribal territory, of which he is kgosi (paramount chief), for the hotly contested 2019 general elections. Two perspectives emerged on Khama’s approach, which was labelled loosely as ‘tribalism’. One school of thought was that the Westernised and bi-racial Khama was not socialised sufficiently into Tswana culture and tribal life to be a tribalist. Therefore, he was said to be using cunningly a colonial-style strategy of divide- and-rule to achieve his agenda. The second school of thought opined that Khama was a ‘shameless tribalist’ hell-bent on stoking ‘tribalism’ among the ‘Bangwato’ in order to bring Masisi’s government to its knees. This article, Alternation Special Edition 36 (2020) 210 - 249 210 Print ISSN 1023-1757; Electronic ISSN: 2519-5476; DOI https://doi.org/10.29086/2519-5476/2020/sp36a10 The Discourse of Tribalism in Botswana’s 2019 General Elections however, observes that Khama’s approach was not entirely new in Botswana’s politics, but only bigger in scale, and instigated by a paramount chief and former President. -

School of Graduate Studies Department of Political Science and International Relations

SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THE PRACTICE OF UPHOLDING CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS IN ETHIOPIA AND BOTSWANA: CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS BY ALEMU ARAGE JULY, 2020 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THE PRACTICE OF UPHOLDING CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS IN ETHIOPIA AND BOTSWANA: CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS BY ALEMU ARAGE ADVISOR KASSAHUN BIRHANU (PROFESSOR) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES OF ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF MASTERS OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AND DIPLOMACY JULY, 2020 ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA Declaration I hereby declare that the thesis entitled: The Practice of Upholding Civil and Political Rights in Ethiopia and Botswana: A Comparative Analysis, submitted to award of the Degree of Master of Arts in International Relations and Diplomacy at Addis Ababa University, is my original research work that has not been presented anywhere for any degree. To the best of the researcher„s knowledge, all sources of material used for the thesis have been fully acknowledged. Name: Alemu Arage Signature: ______________ Date: July, 2020 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS THE PRACTICE OF UPHOLDING CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS IN ETHIOPIA AND BOTSWANA: CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS BY ALEMU ARAGE APPROVED BY BOARD OF EXAMINERS __________________________ ____________ __________ ADVISOR SIGNATURE DATE __________________________ _______________ ____________ EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE __________________________ _______________ ____________ EXAMINER SIGNATURE DATE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and for most, my deepest gratitude belongs to my advisor Professor Kassahun Birhanu whose valuable comments and support that he gave me to complete this research thesis. -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117