Headmark 019 Feb 1980

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FROM CRADLE to GRAVE? the Place of the Aircraft

FROM CRADLE TO GRAVE? The Place of the Aircraft Carrier in Australia's post-war Defence Force Subthesis submitted for the degree of MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES at the University College The University of New South Wales Australian Defence Force Academy 1996 by ALLAN DU TOIT ACADEMY LIBRARy UNSW AT ADFA 437104 HMAS Melbourne, 1973. Trackers are parked to port and Skyhawks to starboard Declaration by Candidate I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgment is made in the text of the thesis. Allan du Toit Canberra, October 1996 Ill Abstract This subthesis sets out to study the place of the aircraft carrier in Australia's post-war defence force. Few changes in naval warfare have been as all embracing as the role played by the aircraft carrier, which is, without doubt, the most impressive, and at the same time the most controversial, manifestation of sea power. From 1948 until 1983 the aircraft carrier formed a significant component of the Australian Defence Force and the place of an aircraft carrier in defence strategy and the force structure seemed relatively secure. Although cost, especially in comparison to, and in competition with, other major defence projects, was probably the major issue in the demise of the aircraft carrier and an organic fixed-wing naval air capability in the Australian Defence Force, cost alone can obscure the ftindamental reordering of Australia's defence posture and strategic thinking, which significantly contributed to the decision not to replace HMAS Melbourne. -

Orders, Medals and Decorations

Orders, Medals and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Lower Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 1 December 2016 at 12.00 noon and 2.30 pm Public viewing: Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Monday 28 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 29 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 30 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 83 Price £15 Enquiries: Paul Wood, David Kirk or James Morton Cover illustrations: Lot 239 (front); lot 344 (back); lot 35 (inside front); lot 217 (inside back) Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.the-saleroom.com, www.numisbids.com and www.sixbid.com. Morton & Eden Ltd offers an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the under- standing that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connec- tion. -

April 2008 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE april 2008 VOL. 31 no.2 The official journal of The ReTuRned & SeRviceS League of austraLia POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListening Branch incorporated • Po Box 3023 adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • established 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL ANZAC Day In recognition of the great sacrifice made by the men and women of our armed forces. 2008ANZAC DAY 2008 Trinity Church SALUTING DAIS EX-SERVICE CONTINGENTS VIP PARKING DAIS 2 JEEPS/HOSPITAL CARS JEEPS/HOSPITAL ADF CONTINGENTS GUEST PARKING ANZAC Day March Forming Up Guide Page 14-15 The Victoria Cross (VC) Page 12, 13 & 16 A Gift from Turkey Page 27 ANZAC Parade details included in this Edition of Listening Post Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL Osborne Park 9445 5000 Midland 9267 9700 Belmont 9477 4444 O’Connor 9337 7822 Claremont 9284 3699 East Vic Park Superstore 9470 4949 Joondalup 9301 4833 Perth City Mega Store 9227 4100 Mandurah 9535 1246 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. Just show your membership card! I put my name on it.” 2 The Listening Post april 2008 www.northsidenissan.com.au ☎ 9409 0000 14 BERRIMAN DRIVE, WANGARA ALL NEW MICRA ALL NEW DUALIS 5 DOOR IS 2 CARS IN 1! • IN 10 VIBRANT COLOURS • HATCH AGILITY • MAKE SURE YOU WASH • SUV VERSATILITY SEPARATELY • SLEEK - STYLISH DUALIS FROM FROM $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 14,990 AWAY 25,990 AWAY * Metallic Paint Extra. Manual Transmission. $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 15576 AWAY 38909 AWAY Metallic paint (as depicted) $300 extra. TIIDA ST NAVARA ST-X SEDAN OR HATCH MANUAL TURBO DIESEL MANUAL • 6 speed manual transmission • Air conditioning • CD player • 126kW of power/403nm torque • 3000kg towing capacity • Remote keyless entry • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • Alloy wheels • ABS brakes • Dual airbags $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 43888 AWAY 44265 AWAY NOW WITH ABS BRAKES FREE BULL BAR, TOW BAR FREE & SPOTTIES $ 1000 FUEL Metallic paint (as depicted) $300 extra. -

Australian Department of Defence Annual Report 2001

DEFENCE ANNUAL REPORT 2001-02 HEADLINE RESULTS FOR 2001-02 Operational S Defence met the Government’s highest priority tasks through: effectively contributing to the international coalition against terrorism playing a major role in assisting East Timor in its transition to independence strengthening Australia’s border security increasing the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) counter-terrorism capability providing substantial assistance to the Bougainville and Solomon Islands’ peace processes supporting civil agencies in curbing illegal fishing in Australian waters. S The ADF was at its highest level of activity since the Vietnam war. Social S 86 per cent of Australians said they were proud of the ADF – the highest figure recorded over the past 20 years. 85 per cent believed the ADF is effective and 87 per cent considered the ADF is well trained. Unacceptable behaviour in the ADF continued to be the community’s largest single concern. (Defence community attitudes tracking, April 2002) S ADF recruiting: Enlistments were up, Separations were down, Army Reserve retention rates were the highest for 40 years. S The new principles-based civilian certified agreement formally recognised a balance between employees’ work and private commitments. S Intake of 199 graduate trainees was highest ever. S Defence was awarded the Australian Public Sector Diversity Award for 2001. HEADLINE RESULTS FOR 2001-02 Financial S Defence recorded a net surplus of $4,410 million (before the Capital Use Charge of $4,634 million), when compared to the revised budget estimate of $4,772 million. S The net asset position is $45,589 million, an increase of $1,319 million or 3% over 2000-01. -

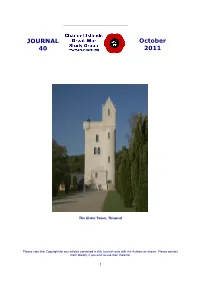

Channel Island Headstones for the Website

JOURNAL October 40 2011 The Ulster Tower, Thiepval Please note that Copyright for any articles contained in this Journal rests with the Authors as shown. Please contact them directly if you wish to use their material. 1 Hello All I do not suppose that the global metal market features greatly in Great War journals and magazines, but we know, sometimes to our cost, that the demand from the emerging economies such as Brazil, China and India are forcing prices up, and not only for newly manufactured metals, but also reclaimed metal. There is a downside in that the higher prices are now encouraging some in the criminal fraternity to steal material from a number of sources. To me the most dangerous act of all is to remove railway trackside cabling, surely a fatal accident waiting to happen, while the cost of repair can only be passed onto the hard-pressed passenger in ticket price rises, to go along with the delays experienced. Similarly, the removal of lead from the roofs of buildings can only result in internal damage, the costs, as in the case of the Morecambe Winter Gardens recently, running into many thousands of pounds. Sadly, war memorials have not been totally immune from this form of criminality and, there are not only the costs associated as in the case of lead stolen from church roofs. These thefts frequently cause anguish to the relatives of those who are commemorated on the vanished plaques. But, these war memorial thefts pale into insignificance by comparison with the appalling recent news that Danish and Dutch marine salvage companies have been bringing up components from British submarine and ships sunk during the Great War, with a total loss of some 1,500 officers and men. -

Medal for Gallantry (Mg)

MEDAL FOR GALLANTRY (MG) Australian Army Sergeant C For acts of gallantry in action in hazardous circumstances as a team commander, Special Operations Task Group on Operation SLIPPER in Afghanistan. Sergeant C displayed inspirational leadership and successive acts of gallantry, undoubtedly saving lives and ensuring mission success. To protect wounded soldiers and with complete disregard for his safety, Sergeant C exposed himself to draw fire and lead assaults on insurgent positions. His selfless and courageous conduct was of the highest order, and in keeping with the finest traditions of Australian special operations forces, the Australian Army and the Australian Defence Force. Sergeant Blaine Flower DIDDAMS, deceased, WA For acts of gallantry in action in hazardous circumstances as a patrol commander, Special Operations Task Group Rotation XVII on Operation SLIPPER in Afghanistan on 2 July 2012. On 2 July 2012, Sergeant Diddams displayed inspirational leadership and selfless courage in extremely hazardous circumstances. To support his patrol and ensure mission success, he knowingly exposed himself to draw fire and lead assaults on insurgent positions. His leadership and selfless acts of gallantry, which ultimately cost his life, were of the highest order and in keeping with the finest traditions of Australian special operations forces, the Australian Army and the Australian Defence Force. 468 Any enquiries regarding the above awards should be directed to Defence Media Liaison on (02)6265 3343 COMMENDATION FOR GALLANTRY Australian Army Corporal A For acts of gallantry in action as a deputy patrol commander, Special Operations Task Group, on Operation SLIPPER in Afghanistan. During a prolonged and hazardous operation, Corporal A exhibited inspirational leadership, outstanding courage, and exceptional endurance. -

Headmark 075 20-1 February-April 1994

AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE INC The Australian Naval Institute was formed and incorporated in the Australian Capital Territory in 1975. The main objects of the Institute arc: • To encourage and promote the advancement of knowledge related to the Navy and the mari- time profession, • to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas concerning subjects related to the Navy and the maritime profession, and • to publish a journal. The Institute is self-supporting and non-profit-making. All publications of the Institute will stress that the authors express their own views and opinions are not necessarily those of the Depart- ment of Defence, the Chief of Naval Staff or the Institute. The aim is to encourage discussion, dissemination of information, comment and opinion and the advancement of professional knowl- edge concerning naval and maritime matters. The membership of the Institute is open to: • Regular Members. Regular membership is open to members of the RAN or RANK and per- sons who having qualified for regular membership, subsequently leave the service. • Associate Members. Associate membership is open to all other persons not qualified to be Regular Members, who profess an interest in the aims of the Institute. • Honorary Members. Honorary membership is open to persons who have made a distinguished contribution to the Navy or the maritime profession, or by past service to the institute. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Australian Naval Institute is grateful for the assistance provided by the corporations listed below. They are demonstrating their support for the aim of the Institute by being members of the "Friends of the Australian Naval Institute" coterie. -

Journal of the Australian Naval Institute

Registered by Australian Post VOLUME 12 Publication No. NBP 0282 FEBRUARY 1986 NUMBER 1 ISSN 0312-5807 JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE (INCORPORATED IN THE ACT) V AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE INC 1 The Australian Naval Institute Inc is incorporated in the Australian Capital Territory. The mam objects of the Institute are a to encourage and promote the advancement of knowledge related to the Navy and the maritime profession. b to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas concerning subjects related to the Navy and the maritime profession, and c to publish a journal 2 The Institute is self supporting and non-profit making The aim is to encourage discussion, dis- semination of information, comment and opinion and the advancement of professional knowledge concerning naval and maritime matters 3 Membership of the Institute is open to — a. Regular Members - Members of the Permanent Naval Forces of Australia b Associate Members - (1) Members of the Reserve Naval Forces of Australia (2) Members of the Australian Military Forces and the Royal Australian Air Force both permanent and reserve (3) Ex-members of the Australian Defence Force, both permanent and reserve components, provided that they have been honourably discharged from that Force. (4) Other persons having and professing a special interest in naval and maritime affairs c Honorary Members - Persons who have made distinguished contributions to the naval or maritime profession or who have rendered distinguished service to the Institute may be elected by the Council to Honorary Membership 4. Joining fee for Regular and Associate members is $5. Annual subscription for both is $20. -

Robert Lehman Papers

Robert Lehman papers Finding aid prepared by Larry Weimer The Robert Lehman Collection Archival Project was generously funded by the Robert Lehman Foundation, Inc. This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on September 24, 2014 Robert Lehman Collection The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028 [email protected] Robert Lehman papers Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Biographical/Historical note................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents note...................................................................................................34 Arrangement note.............................................................................................................. 36 Administrative Information ............................................................................................ 37 Related Materials ............................................................................................................ 39 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................. 41 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 40 Collection Inventory..........................................................................................................43 Series I. General -

Sea Control & Maritime Power Projection for Australia: Maritime Air

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2003 Sea control & maritime power projection for Australia: maritime air power and air warfare Richard T. Menhinick University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Menhinick, Richard T, Sea control & maritime power projection for Australia: maritime air power and air warfare, M.MS-R thesis, Centre for Maritime Policy, University of Wollongong, 2003. -

Surface Warfare

ISSUE 154 FINAL ISSUE – JUNE 2015 Surface Warfare: Taking the Offensive The Indonesian Maritime Doctrine: Realising the Potential of the Ocean The Naval Build-Up in the Philippines National Defence Strategic Policy as a Function of National Leadership An Ocean for my Kingdom World Naval Developments ANZAC Frigate Upgrade sustains WA jobs Fit to be a Frigate? Navigating the Black Ditch: Risks in the Taiwan Strait To Safeguard the Seas WWI Book Reviews JOURNAL OF THE 2 Journal of the Australian Naval Institute Issue 154 3 An e-7a Wedgetail and two f/a-18a Hornets provide a fly past during the Anzac Day 2015 National Ceremony held in Canberra. Contents Australian Naval Institute 2015 Report 4 Message from the President 6 Surface Warfare: Taking the Offensive 8 The Indonesian Maritime Doctrine: Realising the Potential of the Ocean 10 Front page : The Naval Build-Up in the Clearance Divers Philippines 16 are the Australian Defence Forces’ specialist divers. National Defence Strategic Policy as a Clearance Diver Function of National Leadership 19 tasks include specialist diving An Ocean for my Kingdom 23 missions to depths of 54 metres, surface and underwater World Naval Developments 29 demolitions, and the rendering ANZAC Frigate Upgrade safe and disposal sustains WA jobs 32 of conventional explosive ordnance Fit to be a Frigate? 36 and improvised explosive devices. Navigating the Black Ditch: Risks in the Taiwan Strait 39 Ms Diane Bricknell came on board the ANI Headmark project from the start of To Safeguard the Seas 44 a changeover to a more dynamic design, around 10 years ago. -

Headmark 052 14-2 May 1988

Registered by Australia Post VOLUME 14 Publication No. NBP 0282 MAY 1988 NUMBER 2 iSSN 0312-5807 JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE AUSTRALIAN NAVAL INSTITUTE INC 1 The Australian Naval Institute Inc is incorporated in the Australian Capital Territory. The main objects of the Institute are a. to encourage and promote the advancement of knowledge related to the Navy and the maritime profession, b. to provide a forum for the exchange of ideas concerning subjects related to the Navy and the maritime profession, and c. to publish a journal. 2 The Institute is self supporting and non-profit making. The aim is to encourage discussion, dissemination of information, comment and opinion and the advancement of professional knowledge concerning naval and maritime matters. 3. Membership of the Institute is open to — a. Regular Members — Members of the Permanent Naval Forces of Australia. b. Associate Members — (1) Members of the Reserve Naval Forces of Australia. (2) Members of the Australian Military Forces and the Royal Australian Air Force both permanent and reserve. (3) Ex-members of the Australian Defence Force, both permanent and reserve components, provided that they have been honourably discharged from that Force. (4) Other persons having and professing a special interest in naval and maritime affairs. c. Honorary Members — Persons who have made distinguished contributions to the naval or maritime profession or who have rendered distinguished service to the Institute may be elected by the Council to Honorary Membership. 4. Joining fee for Regular and Associate members if $5. Annual subscription for both is $20. 5. Inquiries and application for membership should be directed to: The Secretary, Australian Naval Institute Inc.