The Coastalaska Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SENATE FINANCE COMMITTEE March 30, 2015 2:59 P.M. 2:59:03

SENATE FINANCE COMMITTEE March 30, 2015 2:59 p.m. 2:59:03 PM CALL TO ORDER Co-Chair Kelly called the Senate Finance Committee meeting to order at 2:59 p.m. MEMBERS PRESENT Senator Anna MacKinnon, Co-Chair Senator Pete Kelly, Co-Chair Senator Peter Micciche, Vice-Chair Senator Click Bishop Senator Mike Dunleavy Senator Lyman Hoffman Senator Donny Olson MEMBERS ABSENT None ALSO PRESENT Pam Mueller-Guy, Deaf Service, Southeast Alaska Independent Living (SAIL), Juneau; Robert Kelso, Self, Juneau; Stephen SueWing, Self, Juneau; Mark Miller, Superintendent, Juneau School District, Juneau; Patrick Sidmore, Board Member, Association for the Education of Young Children (AEYC), Juneau; Ron Somerville, Self, Juneau; Ed Buyarski, Southeast Master Gardeners, Juneau; Kara Hollatz, Children, Juneau; Patty Winegar, Self, Juneau; Emily Ferry, Self, Juneau; Averyl Veliz, Self, Juneau; Jorden Nigro, Self, Juneau; Will Muldoon, Self, Juneau; Odin Brudie, Self, Juneau; Andi Story, Member, Juneau School Board, Juneau; Bill Hill, Superintendent, Bristol Bay School District, Bristol Bay; Mary Tonsmeire, Self, Juneau; Daniel Moore, fifth and sixth grade teacher, Chefornak; Lynnette Dihle, Self, Juneau; Jane Alzner, Special Education Teacher, Lower Yukon School District, Kotlik; Hilary Zander, Self, Juneau; Patricia George, Advocacy Chair, Alaska State Literacy Association, Juneau; Anita Evans, Juneau Interpreter Referral Line, Juneau; Deanna Hobbs, High School Student, Juneau; Nancy Seamount, Academic Counselor, Alaska's Learning Network (AKLN), Juneau; Cori -

Who Pays Soundexchange: Q1 - Q3 2017

Payments received through 09/30/2017 Who Pays SoundExchange: Q1 - Q3 2017 Entity Name License Type ACTIVAIRE.COM BES AMBIANCERADIO.COM BES AURA MULTIMEDIA CORPORATION BES CLOUDCOVERMUSIC.COM BES COROHEALTH.COM BES CUSTOMCHANNELS.NET (BES) BES DMX MUSIC BES ELEVATEDMUSICSERVICES.COM BES GRAYV.COM BES INSTOREAUDIONETWORK.COM BES IT'S NEVER 2 LATE BES JUKEBOXY BES MANAGEDMEDIA.COM BES MEDIATRENDS.BIZ BES MIXHITS.COM BES MTI Digital Inc - MTIDIGITAL.BIZ BES MUSIC CHOICE BES MUSIC MAESTRO BES MUZAK.COM BES PRIVATE LABEL RADIO BES RFC MEDIA - BES BES RISE RADIO BES ROCKBOT, INC. BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC BES SOUND-MACHINE.COM BES STARTLE INTERNATIONAL INC. BES Stingray Business BES Stingray Music USA BES STORESTREAMS.COM BES STUDIOSTREAM.COM BES TARGET MEDIA CENTRAL INC BES Thales InFlyt Experience BES UMIXMEDIA.COM BES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC CABSAT Stingray Music USA CABSAT MUSIC CHOICE PES MUZAK.COM PES SIRIUS XM RADIO, INC SDARS 181.FM Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Christian Music) Webcasting 3ABNRADIO (Religious) Webcasting 8TRACKS.COM Webcasting 903 NETWORK RADIO Webcasting A-1 COMMUNICATIONS Webcasting ABERCROMBIE.COM Webcasting ABUNDANT RADIO Webcasting ACAVILLE.COM Webcasting *SoundExchange accepts and distributes payments without confirming eligibility or compliance under Sections 112 or 114 of the Copyright Act, and it does not waive the rights of artists or copyright owners that receive such payments. Payments received through 09/30/2017 ACCURADIO.COM Webcasting ACRN.COM Webcasting AD ASTRA RADIO Webcasting ADAMS RADIO GROUP Webcasting ADDICTEDTORADIO.COM Webcasting ADORATION Webcasting AGM BAKERSFIELD Webcasting AGM CALIFORNIA - SAN LUIS OBISPO Webcasting AGM NEVADA, LLC Webcasting AGM SANTA MARIA, L.P. -

Raven Radio On-Air Annual Meeting December 19Th, 2018

Raven Radio On-Air Annual Meeting December 19th, 2018 Welcome & Order of Things: Becky Meiers, General Manager Introduce the Board: Kenley Jackson, Board Vice President CoastAlaska: Mollie Kabler, CoastAlaska Executive Director Budget Report: Becky Meiers, General Manager Audience Report: Becky Meiers, General Manager Development: Makenzie DeVries, Development Director News: Robert Woolsey, News Director and Katherine Rose, Reporter Programming: Max Kritzer, Program Director Q&A: Becky Meiers, Mollie Kabler Welcome & Order of Things Thank you for joining me this evening for my very 1st Annual Meeting at Raven Radio. My name is Becky Meiers, and I am the General Manager, as well as your host tonight. It is an honor and a privilege to be a part this radio community. I'm excited to join you all - members, volunteers, staff, listeners - at this incredible station. Raven Radio is a lifeline in so many ways. You expect news and information from us - and on that point, we’re there for you every day - but let’s not forget the essential nourishment the music you hear on KCAW feeds your soul. Your social calendar wouldn’t quite be the same without the community events you see on the website and hear on the air. Raven Radio is an essential part of all our lives - sometimes all the time, sometimes just when you need us the most. You make it possible for us to be there for you. As new technologies develop, and as our relationships with audio shift, know that the staff at Raven Radio are always thinking about how to better serve you. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

The Video And/Or Audio Recording of This Performance by Any Means Whatsoever Are Strictly Prohibited

The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever are strictly prohibited. FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Dear Friends, Welcome to A Christmas Carol, with Scrooge, Marley, Tiny Tim and all! “ We are full In living PT’s mission of creating theatre by and for Alaskans, the theatre finds an incredible opportunity--we are charged with working, whenever we can, with Alaskan artists, and giving them the chance to collaborate and interact with the writers, of cheer about designers, actors, and artists that we bring in from outside. We’re simultaneously enriching our Alaskan community and the wider national theatre community through making this, this interaction, this essential part of making live theatre. You, as audience members are essential as well. By showing up and participating Perseverance’s in this art form--just by experiencing it--you’re making it happen, and you keep it happening. Many of you have gone one step further: you’ve supported the theatre own adaptation through your charitable donation. Thank you! We are in the midst of our annual individual giving campaign, and we’re a little more than halfway to our goal. If you of Dicken’s aren’t yet a donor, you’ll find information on giving in the playbill, and donation envelopes in the lobby. Or, donate online at ptalaska.org/donate-now. Thank you! classic, an If you’re one of the families that has joined us tonight through our new program to support Anchorage PTAs, thank you! Please let other families know about the annual holiday opportunity to help your school and save on tickets at the same time. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

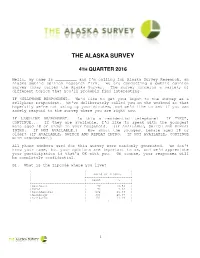

The Alaska Survey

THE ALASKA SURVEY 4TH QUARTER 2016 Hello, my name is _________ and I'm calling for Alaska Survey Research, an Alaska public opinion research firm. We are conducting a public opinion survey today called the Alaska Survey. The survey concerns a variety of different topics that you’ll probably find interesting. IF CELLPHONE RESPONDENT… We’d like to get your input to the survey as a cellphone respondent. We’ve deliberately called you on the weekend so that hopefully we’re not using up your minutes, and we’d like to ask if you can safely respond to the survey where you are right now. IF LANDLINE RESPONDENT… Is this a residential telephone? IF "YES", CONTINUE... If they are available, I’d like to speak with the youngest male aged 18 or older in your household. (IF AVAILABLE, SWITCH AND REPEAT INTRO. IF NOT AVAILABLE…) How about the youngest female aged 18 or older? (IF AVAILABLE, SWITCH AND REPEAT INTRO. IF NOT AVAILABLE, CONTINUE WITH RESPONDENT.) All phone numbers used for this survey were randomly generated. We don’t know your name, but your opinions are important to us, and we'd appreciate your participation if that's OK with you. Of course, your responses will be completely confidential. S1. What is the zipcode where you live? +------------------------------+-------------------------+ | | AREAS OF ALASKA: | | +------------+------------+ | | Count | % | +------------------------------+------------+------------+ |Southeast | 79 | 10.5% | |Rural | 72 | 9.6% | |Southcentral | 192 | 25.6% | |Anchorage | 306 | 40.9% | |Fairbanks | 101 | 13.4% -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-210208-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/08/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122476 Renewal of FM KLGA- 35428 Main 92.7 ALGONA, IA RIVERFRONT 02/04/2021 Granted License FM BROADCASTING OF IOWA, LLC From: To: 0000118612 Renewal of FM WLUM- 63595 Main 102.1 MILWAUKEE, MILWAUKEE RADIO 02/04/2021 Granted License FM WI ALLIANCE, LLC From: To: 0000135142 License To DTV WSBE- 56092 Main 54.0 PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND PBS 02/04/2021 Granted Cover TV RI FOUNDATION From: To: 0000119104 Renewal of FX W230BU 142640 93.9 ROTHSCHILD, WRIG, INC. 02/04/2021 Granted License WI From: To: 0000134509 License To FM KBMK 93533 Main 88.3 BISMARCK, ND EDUCATIONAL 02/04/2021 Granted Cover MEDIA FOUNDATION From: To: 0000134657 License To FM KRNN 17049 Main 102.7 JUNEAU, AK KTOO Public Media 02/04/2021 Granted Cover From: To: Page 1 of 4 REPORT NO. PN-2-210208-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 02/08/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122436 Modification FM WYKC 165997 Main 99.1 WHITEFIELD, Educational Media 02/04/2021 Granted of License NH Foundation From: To: 0000120154 License To LPT W34FG- 182477 34 BOWLING GRAY TELEVISION -

The M Street Journal Radio's Journal of Record ' EW YORK NASHVILLE CAPSTAR ACROSS AFRICA

The M Street Journal Radio's Journal of Record ' EW YORK NASHVILLE CAPSTAR ACROSS AFRICA. Capstar Broadcasting Partners will spend $60 million for twenty stations in four separate transactions covering five markets. Terms of the individual deals weren't disclosed. Two of the deals involve Point Communications, which is the managing partner of six stations in Madison, WI and owns five in the Roanoke - Lynchburg area, owned through a subsidiary. In Madison, the stations are standards WTSO; CHR WZEE; news -talk WIBA; rock WIBA -FM; new rock WMAD -FM, Sun Prairie, WI; and soft AC WMLI, Sauk City, WI. In Roanoke - Lynchburg -- oldies simulcast WLDJ, Appomattox and WRDJ, Roanoke; urban oldies WJJS, Lynchburg; and dance combo WJJS -FM, Vinton, and WJJX, Lynchburg. The third deal gives Capstar three stations in the Yuma, AZ market, including oldies KBLU, country KTTI, and classic rocker KYJT, from Commonwealth Broadcasting of Arizona, LLC. Finally, COMCO Broadcasting's Alaska properties, which include children's KYAK, CHR KGOT, and AC KYMG, all Anchorage; and news -talk KIAK, country KIAK -FM, and AC KAKQ -FM, all Fairbanks. WE DON'T NEED NO STINKIN' LICENSE . It's spent almost ten weeks on the air without a license, but the new religious -programmed station on 105.3 MHz in the Hartford, CT area, is being investigated by the Commission's New England Field Office. According to the Hartford Courant, Mark Blake is operating the station from studios in Bloomfield, CT, and says that he "stands behind" the station's operation. Although there have been no interference complaints filed, other stations in the area are claiming they are losing advertising dollars to the pirate. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Tom Robenolt, Perseverance Theatre (907) 364-2421 x228 [email protected] Art Rotch, Perseverance Theatre (907) 364 2421 x229 [email protected] Perseverance Theatre Opens 37th Season of Professional Theatre in Juneau with William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Othello August 31, 2015 - Juneau – Perseverance Theatre opens its 37th season with The Tragedy of Othello, one of Shakespeare’s best known plays. Othello is a ‘moorish,’ or African, general who has fought many wars for most of his life. While leading an army for Venice, he meets his wife Desdemona, a Venetian woman from a prominent family, and decides to bring his new wife with his army to fight in Cyprus. Meanwhile, Iago, Shakespeare’s most complex and mysterious villain, is upset by a minor slight when a rival, Cassio, is promoted instead of Iago himself. Once they arrive in Cyprus, Iago manipulates Othello and Cassio in a cold hearted act of petty vengeance. Othello is well known for its direct style and large number of intimate, conspiratorial scenes, framed by moments of violence. The cast features Jamil Mangan as Othello, previously seen at Perseverance as Asagai in A Raisin in the Sun; Kat Wodtke, making her Perseverance debut as Desdemona; and Brandon Demery as Iago, whose extensive list of Perseverance Theatre acting credits include the role of Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, Perseverance’s most recent production by the bard. The rest of the cast features actors from Anchorage, Juneau, and Fairbanks. Casting some of the best actors in the state is more possible now that Perseverance mounts seasons in two of Alaska’s largest cities, Juneau and Anchorage. -

Fact Finding Investigation No. 30 ______

FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION _______________________________________________ FACT FINDING INVESTIGATION NO. 30 _______________________________________________ COVID-19 IMPACT ON CRUISE INDUSTRY _______________________________________________ INTERIM REPORT: ECONOMIC IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON THE CRUISE INDUSTRY IN ALASKA, WASHINGTON, AND OREGON October 20, 2020 _______________________________________________ 1 Table of Contents I. Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................3 II. Fact Finding Method ........................................................................................................4 III. Observations.....................................................................................................................5 A. Cruise Industry in Alaska ..............................................................................................5 B. Anchorage................................................................................................................... 11 C. Seward ........................................................................................................................ 13 D. Whittier....................................................................................................................... 14 E. Juneau ......................................................................................................................... 15 F. Ketchikan ................................................................................................................... -

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission Th News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 445 12 St., S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE Federal Communications Commission th News Media Information 202 / 418-0500 445 12 St., S.W. Internet: http://www.fcc.gov Washington, D.C. 20554 TTY: 1-888-835-5322 DA 13-1468 Released: June 28, 2013 FCC CONTINUES 2013 EEO AUDITS On June 26, 2013, the Federal Communications Commission mailed the second of its Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO) audit letters for 2013 to randomly selected radio stations. In accordance with the provisions of Section 73.2080(f)(4) of the Commission’s EEO rules, the FCC annually audits the EEO programs of randomly selected broadcast licensees. Each year, approximately five percent of all radio and television stations are selected for EEO audits. Attached are a list of the radio stations to which the audit letters were sent, as well as the text of the June 26, 2013 audit letter. The list and the letter can also be viewed by accessing the Media Bureau’s current EEO headline page on the FCC website at http://www.fcc.gov/encyclopedia/equal-employment-opportunity-2013-headlines . For stations that have a website and five or more full-time employees: We remind you that you must post your most recent EEO public file report on your website by the deadline by which it must be placed in the public file, in accordance with 47 C.F.R. § 73.2080(c)(6). This will be examined as part of the audit. Failure to post the required report on a station website is a violation of the EEO Rule and subject to sanctions, including a forfeiture.