The Representation of the Indigenous Peoples Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Madero and Sdarez Shot to Prison

--—1 A. i CAVALRY IN FRONT OF THE NATIONAL PALACE MMIfiwww THE MORRIS CO. CHRONICLE r k 1 nw A Thdr Arriral- !; ■ TT C ■ ■■■■ -— ■■■■»■■■-! MILITANTS PUN f < "I & SURDAM, Publishers. MADERO AND PIEHSON SDAREZ SHOT | MAIL J and Departure J* *Mm MORRISTOWN N. J. ATTACK ON KING DEAD ON WAY TO PRISON for Dispatch England Is In acute need of elastic British Royal Family in Fear Tim* of Closing of M»ll» window glass. at P. O., Morristown. , of * Suffragettes «.0« A. It. Now York and ba- skirted wom- The President ol Mexico and His Yice-Pres:d3nt Die De- Newark, However, as for hobble Deposed yond, and Whlppany. ’’ York en, how can she expect to "win In a T.f* s K. P. O. sast. Now and bsyond. walk?” on a " Including fenceless Ride from Palace to TERROR ■ M a R. P. O. west. Midn'git Penitentiary, NATION IS IN GREAT all Western states. Ill " *a New Jersey & Penn R. *» A Peruvian aviator to fly " proposes and the Whole Civilized World Stands 9.60 • Mt. Freedom. over the Alps. In a Peruvian bark, Aghast 9.66 Newark, New York and be- Two Women Are Captured—Throw* yond. probably. i 10.10 • Whlppany. When Ar- •• Books at Magistrate 1S.M a N. Y., Scranton A Buffala, K. P. O. including Dover, "Bashi-baxoukesses" may fit the raigned—Their Act Is Highly * Rookaway, Boonton, Wnar crime, but it’s altogether too hard to Vandals. ton, Succasunna, o Central GUARDS SAY THEY TRIED TO “ESCAPE” Applauded by Branch and all stations pronounce. -

Gallery of Mexican Art

V oices ofMerico /January • March, 1995 41 Gallery of Mexican Art n the early the 1930s, Carolina and Inés Amor decided to give Mexico City an indispensable tool for promoting the fine arts in whatI was, at that time, an unusual way. They created a space where artists not only showed their art, but could also sell directly to people who liked their work. It was a place which gave Mexico City a modem, cosmopolitan air, offering domestic and international collectors the work of Mexico's artistic vanguard. The Gallery of Mexican Art was founded in 1935 by Carolina Amor, who worked for the publicity department at the Palace of Fine Arts before opening the gallery. That job had allowed her to form close ties with the artists of the day and to learn about their needs. In an interview, "Carito" —as she was called by her friends— recalled a statement by the then director of the Palace of Fine Arts, dismissing young artists who did not follow prevailing trends: "Experimental theater is a diversion for a small minority, chamber music a product of the court and easel painting a decoration for the salons of the rich." At that point Carolina felt her work in that institution had come to an end, and she decided to resign. She decided to open a gallery, based on a broader vision, in the basement of her own house, which her father had used as his studio. At that time, the concept of the gallery per se did not exist. The only thing approaching it was Alberto Misrachi's bookstore, which had an The gallery has a beautiful patio. -

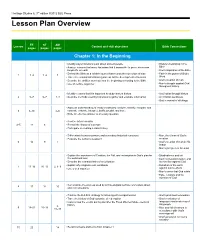

Heritage Studies 6, 3Rd Ed. Lesson Plan Overview

Heritage Studies 6, 3rd edition ©2012 BJU Press Lesson Plan Overview TE ST AM Lesson Content and skill objectives Bible Connections pages pages pages Chapter 1: In the Beginning • Identify ways historians learn about ancient people • History’s beginning in the • Analyze reasons that many historians find it impossible to prove when man Bible began life on earth • God’s inspiration of the Bible • Defend the Bible as a reliable source that records the true origin of man • Faith in the power of God’s 1 1–4 1–4 1 • Trace the evolutionist’s thinking process for the development of humans Word • Describe the abilities man had from the beginning according to the Bible • God’s creation of man • Use an outline organizer • Man’s struggle against God throughout history • Identify reasons that it is important to study ancient history • God’s plan through history 2 5–7 5–7 1, 3 • Describe methods used by historians to gather and evaluate information • A Christian worldview • God in control of all things • Apply an understanding of essay vocabulary: analyze, classify, compare and contrast, evaluate, interpret, justify, predict, and trace 3 8–10 4–6 • Write an effective answer to an essay question • Practice interview skills 4–5 11 8 • Record the history of a person • Participate in creating a class history • Differentiate between primary and secondary historical resources • Man, the climax of God’s • Evaluate the author’s viewpoint creation 6 12 9 7 • God’s creation of man in His image • Man’s job given at Creation • Explain the importance of Creation, the Fall, and redemption in God’s plan for • Disobedience and sin the world and man • Each civilization’s failure and • Describe the characteristics of a civilization its rebellion against God • Explain why religions exist worldwide • Rebellion of the earth 7 13–16 10–13 2, 8–9 • Use a web organizer against man’s efforts • Man’s sense that God exists • False religions and the rejection of God • Demonstrate the process used by archaeologists to draw conclusions about 8 17 14 10 ancient civilizations • Practice the E.A.R.S. -

Disfigured History: How the College Board Demolishes the Past

Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past A report by the Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton 420 Madison Avenue, 7th Floor Published November, 2020. New York, NY 10017 © 2020 National Association of Scholars Disfigured History How the College Board Demolishes the Past Report by David Randall Director of Research, National Assocation of Scholars Introduction by Peter W. Wood President, National Association of Scholars Cover design by Beck & Stone; Interior design by Chance Layton Published November, 2020. © 2020 National Association of Scholars About the National Association of Scholars Mission The National Association of Scholars is an independent membership association of academics and others working to sustain the tradition of reasoned scholarship and civil debate in America’s colleges and universities. We uphold the standards of a liberal arts education that fosters intellectual freedom, searches for the truth, and promotes virtuous citizenship. What We Do We publish a quarterly journal, Academic Questions, which examines the intellectual controversies and the institutional challenges of contemporary higher education. We publish studies of current higher education policy and practice with the aim of drawing attention to weaknesses and stimulating improvements. Our website presents educated opinion and commentary on higher education, and archives our research reports for public access. NAS engages in public advocacy to pass legislation to advance the cause of higher education reform. We file friend-of-the-court briefs in legal cases defending freedom of speech and conscience and the civil rights of educators and students. We give testimony before congressional and legislative committees and engage public support for worthy reforms. -

Paradores & Pousadas

PARADORES & POUSADAS HISTORIC LODGINGS OF SPAIN & PORTUGAL April 5-19, 2018 15 days for $5,178 total price from Dallas-Fort Worth ($4,495 air & land inclusive plus $683 airline taxes and fees) This tour is provided by Odysseys Unlimited, six-time honoree Travel & Leisure’s World’s Best Tour Operators award. An Exclusive Small Group Tour for Alumni, Parents, and Friends of Texas Christian University Dear TCU Alumni, Parents, and Friends, Join us on a special 15-day small group journey to discover the best of the Iberian Peninsula in Portugal and Spain. Our special two-week journey offers captivating sights, excellent cuisine, and memorable experiences. We begin in Lisbon, where our touring includes iconic Belém Tower, then see the National Palace of Queluz. Next, we visit the Alentejo region, staying in charming Evora – a UNESCO World Heritage site – in one of Portugal’s finestpousadas . Crossing into Spain, we visit Mérida, which boasts outstanding Roman ruins. Then, we enjoy Seville, the UNESCO World Heritage site of Cordoba, and Granada’s extraordinary Alhambra and Generalife Gardens. Our group explores Toledo, Spain’s medieval capital, concluding our tour in sophisticated Madrid. Space on this exclusive TCU departure is limited to a total of just 24 guests and will fill quickly. We encourage you to reserve your place quickly. Frog for Life, Kristi McLain Hoban ’75 ’76 Associate Vice Chancellor, University Advancement Phone: 817-257-5427 [email protected] TCU RESERVATION FORM – PARADORES & POUSADAS Enclosed is my/our deposit for $______ ($500 per person) for ____ person(s) on Paradores & Pousadas depart- ing April 5, 2018. -

El Paréntesis Fílmico De Best Maugard Eduardo De La Vega Alfaro | Elisa Lozano Índice

El paréntesis fílmico de Best Maugard Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro | Elisa Lozano Índice Fecha de aparición: Octubre 2016 ISBN: en trámite 5 Editorial Correcamara.com.mx Textos Elisa Lozano Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro 6 Adolfo Best Maugard Diseño Lourdes Franco © D.R. Texto Elisa Lozano Notas sobre los prolegómenos © D.R. Texto Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro 8 fílmicos de Adolfo Best Maugard Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro Best Maugard 22 y su equipo de producción: una nueva forma de filmar Elisa Lozano 50 Documentos El contenido y las opiniones expresadas por los autores no necesariamente reflejan la postura del editor de la publicación. Se autoriza cualquier reproducción parcial o total de los contenidos o imágenes de la publicación, siempre y cuando sea ©S.M. Eisenstein, Santa Camaleoncita dibujo realizado durante el rodaje de ¡Qué Viva Mé- sin fines de lucro o para usos estrictamente académicos, citando invariablemente la fuente sin alteración del contenido xico! , en la hacienda de Tetlapayac. Tomado de Eduardo de la Vega, Del muro a la pantalla: S:M.Eisenstein y el arte pictórico mexicano, México, Conaculta, Imcine, canal 22, Universidad y dando los créditos autorales. de Guadalajara, 1997. Editorial Adolfo Best Maugard A principios de 1993, los Estudios Churubusco todavía ocupaban el enorme predio de Río Churubusco pero comenzaban ya los preparativos para su remodelación, con el fin de dar cabida al Centro Nacional de las Artes que vendría a ocupar la mitad del terreno. Entonces había en los estudios una bodega repleta de latas de pelícu- Adolfolas y materiales publicitariosBest que era necesario Maugard desalojar. -

Encuesta a Públicos De Museos 2008-2009 Informe De Resultados

1 2 Encuesta a públicos de museos 2008-2009 Informe de resultados Eliud Silva, Ulises Vázquez y Fernando Hernández Coordinación Nacional de Desarrollo Institucional Julio 2009 3 4 CONTENIDO I. Introducción 7 II. Conocimiento, Características y opinión sobre el museo 9 II.1 Asistencia previa al museo 9 II.2 ¿Cómo se enteró de la existencia del museo? 10 II.3 Razón principal de su visita hoy 11 II.4 Museos visitados en los últimos doce meses 12 II.5 Cuando usted era niño ¿Sus padres lo llevaban a visitar museos? 13 II.6 ¿Todas las personas que viven en su casa suelen visitar museos? 14 II.7 Motivo de no visita 15 II.8 Escala de expectativas 16 II.9 Otras actividades 17 II.10 Actividades interactivas 18 II.11 Servicios 19 II.11.1 Personal 19 II.11.2 Vigilancia 20 II.11.3 Iluminación 22 II.11.4 Fichas técnicas 23 II.11.5 Señalamientos 25 II.11.6 Baños 26 II.11.7 Tienda y cafetería 28 II.12 Medio de transporte 29 III. Asistencia a otros recintos culturales 30 III.1 Frecuencia de visita a espacios culturales 30 III.2 Tiempo de traslado a espacios culturales 31 IV. Hábitos e importancia del uso de medios de comunicación 31 IV.1 Tiempo invertido 31 IV.2 Importancia 33 V. Perfil sociodemográfico de los visitantes 33 V.1 Tamaño de grupo 33 V.2 Tipo de grupo 34 V.3 Procedencia 35 V.3.1 Distrito Federal 36 V.3.2 Puebla 37 V.3.3 Jalisco 38 V.4 Pirámides de población visitantes versus residentes (Sexo y Edad) 39 V.4.1 Distrito Federal 39 V.4.2 Puebla 40 V.4.3 Jalisco 41 5 V.5 Pirámides de población de visitantes de los museos (Sexo y Edad) 42 V.5.1 Distrito Federal 42 V.5.2 Puebla 43 V.5.3 Jalisco 44 V.6 Escolaridad 45 V.7 Ocupación 47 V.8 Número de focos 49 V.9 Otra manera de ver la procedencia 50 V.10 Contraste descriptivo de perfil de públicos 53 Anexos 55 I. -

Divisions in Mexican Support of Republican Spain

1 Divisions In Mexican Support Of Republican Spain Carlos Nava [email protected] (214) 245-8209 Presented to the History Department, Southern Methodist University In completion of the Undergraduate History Junior Seminar Research Paper Requirement HIST 4300 Dr. James K. Hopkins Southern Methodist University 05/05/2014 2 On July 17, 1936 the news of the Nationalist uprising in Morocco was confirmed by a radio station at Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, after General Franco alerted his fellow conspirators in the mainland with a telegram that the uprising against the Popular Front government of Spain had begun.1 General Quiepo de Llano occupied Seville after bitter fighting on July 18; General Varela held the port of Cádiz and the eastern coast down to Algeciras near Gibraltar. General Miguel Cabanellas rose in Zaragoza; in Castile the rebellion placed the principal towns In Nationalist hands, and General Mola controlled Pamplona, the capital of Navarre by July 19.2 The initial plan of the coup was for the Army of Africa to mobilize in the early morning of July 18, to be followed 24 hours later by the Army in Spain with the goals of capturing the country’s major cities and communication centers. This would be followed with the ferrying of Franco’s African Army to the peninsula by Navy ships that had joined the rebellion. The forces would converge in Madrid and force the transfer of power, which had happen numerous times in recent Spanish history. However, the uprising of July 17 failed in its initial goal of toppling the Republic in a swift coup. -

Frida Kahlo I Diego Rivera. Polski Kontekst

Polski kontekst I Polish context SPIS TREŚCI TABLE OF CONTENTS 9—11 7 Jacek Jaśkowiak 135—148 Helga Prignitz-Poda Prezydent Miasta Poznania I President of the City of Poznań Diego Rivera – prace I Diego Rivera – works Gdyby Frida była wśród nas… I If Frida were among us… 187—187 Helga Prignitz-Poda 19—19 Alejandro Negrín Nickolas Muray Ambasador Meksyku w Polsce I Ambassador of Mexico to Poland Frida Kahlo i Diego Rivera w Polsce: uniwersalizm kultury meksykańskiej 195—195 Ariel Zúñiga Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera in Poland: the Universal Nature of Mexican Art O Bernice Kolko… I On Bernice Kolko… x1— 13 Anna Hryniewiecka 211—211 Dina Comisarenco Mirkin Dyrektor Centrum Kultury ZAMEK w Poznaniu I Director of ZAMEK Culture Centre in Poznań Grafiki Fanny Rabel (artystki w wieku pomiędzy sześćsetnym Frida. Czas kobiet I Frida. Time of Women i dwutysięcznym rokiem życia) I Graphic works by Fanny Rabel (artist between 600 and 2000 years of age) 17—17 Helga Prignitz-Poda Frida Kahlo i Diego Rivera. Polski kontekst. Sztuka meksykańska w wymianie kulturowej 135—224 Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Polish context. Mexican Art in Cultural Exchange O Fanny Rabel I About Fanny Rabel 17— 52 Elena Poniatowska 135—225 Frida Kahlo o Fanny Rabel, sierpień 1945 Frida Kahlo Frida Kahlo about Fanny Rabel, August 1945 0 53—53 Diego Rivera 227—227 Helga Prignitz-Poda Frida Kahlo i sztuka Meksyku I Frida Kahlo and Mexican Art Kolekcja prac z Wystawy sztuki meksykańskiej z 1955 roku w zbiorach Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie I Works from the 1955 Exhibition -

The Geographic Limits to Modernist Theories of Intra-State Violence

The Power of Ethnicity?: the Geographic Limits to Modernist Theories of Intra-State Violence ERIC KAUFMANN Reader in Politics and Sociology, Birkbeck College, University of London; Religion Initiative/ISP Fellow, Belfer Center, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Box 134, 79 John F. Kennedy St., Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] ——————————————————————————————————————————— Abstract This paper mounts a critique of the dominant modernist paradigm in the comparative ethnic conflict literature. The modernist argument claims that ethnic identity is constructed in the modern era, either by instrumentalist elites, or by political institutions whose bureaucratic constructions give birth to new identities. Group boundary symbols and myths are considered invented and flexible. Territorial identities in premodern times are viewed as either exclusively local, for the mass of the population, or ‘universal’, for elites. Primordialists and ethnosymbolists have contested these arguments using historical and case evidence, but have shied away from large-scale datasets. This paper utilizes a number of contemporary datasets to advance a three-stage argument. First, it finds a significant relationship between ethnic diversity and three pre- modern variables: rough topography, religious fractionalization and world region. Modernist explanations for these patterns are possible, but are less convincing than ethnosymbolist accounts. Second, we draw on our own and others’ work to show that ethnic fractionalization (ELF) significantly predicts the incidence of civil conflict, but not its onset . We argue that this is because indigenous ethnic diversity is relatively static over time, but varies over space. Conflict onsets, by contrast, are more dependent on short-run changes over time than incidents, which better reflect spatially-grounded conditioning factors. -

International Women's Day 2018

Libros Latinos P.O. Box 1103 Redlands CA 92373 Tel: 800-645-4276 Fax: 909-335-9945 [email protected] www.libroslatinos.com Terms: All prices are net to all, and orders prepaid. Books returnable within ten days of receipt if not as described. Please order by book ID number. International Women's Day 2018 1. 10 RECOMENDACIONES PARA EL USO NO SEXISTA DEL LENGUAJE. 2a ed. México: Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación, (CONAPRED)/Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres, (INMUJERES)/Secretaría del Trabajo y Previsión Social, (STPS), (Textos del Caracol, No. 1), 2009. Second edition. ISBN: 9786077514206. 32p., illus., glossary, bibl., wrps, tall. Paperback. New. (139619) $10.00 Ten recommendations for using non-sexist language. Includes the following sections: "Lenguaje y sexismo" and "Normatividad sobre el uso no sexista del lenguaje". Printed on glossy coated stock 2. Abréu, Dió-genes. A PESAR DEL NAUFRAGIO. VIOLENCIA DOMÉSTICA Y EL EJERCICIO DEL PODER. TESTIMONIOS DOMINICANOS DESDE NEW YORK. Santo Domingo: The Author, 2005. First edition. ISBN: 99934 33 99 3. 382p., photos, glossary, bibl., wrps. Paperback. Very Good. (99666) $45.00 Cases in domestic violence among Dominicans resident in New York based on personal testimony 3. Acevedo, Carlos. CUADERNOS DE PERFÍL BIOGRÁFICO DE MARGARITA MEARS: PRIMERA OBSTETRA QUE EJERCIÓ EN REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA ESTABLECIÓ EN PUERTO PLATA LA PRIMERA CLÍNICA DE MATERNIDAD QUE SE CONOCIÓ EN EL PAÍS Vino a reglarnos su abnegado espiritu de filantropia. Santo Domingo: Cuadernos de la Historia de Puerto Plata, 2014. First edition. 31p., photos, illus., bibl., wrps. Paperback. Fine. (177315) $10.00 A brief biography on Margarita Mears, the first woman in the Dominican Republic to become an obstetricion and founder of the first maternity clinic in the nation. -

History of Inter-Group Conflict and Violence in Modern Fiji

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship History of Inter-Group Conflict and Violence in Modern Fiji SANJAY RAMESH MA (RESEARCH) CENTRE FOR PEACE AND CONFLICT STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY 2010 Abstract The thesis analyses inter-group conflict in Fiji within the framework of inter-group theory, popularised by Gordon Allport, who argued that inter-group conflict arises out of inter-group prejudice, which is historically constructed and sustained by dominant groups. Furthermore, Allport hypothesised that there are three attributes of violence: structural and institutional violence in the form of discrimination, organised violence and extropunitive violence in the form of in-group solidarity. Using history as a method, I analyse the history of inter-group conflict in Fiji from 1960 to 2006. I argue that inter- group conflict in Fiji led to the institutionalisation of discrimination against Indo-Fijians in 1987 and this escalated into organised violence in 2000. Inter-group tensions peaked in Fiji during the 2006 general elections as ethnic groups rallied behind their own communal constituencies as a show of in-group solidarity and produced an electoral outcome that made multiparty governance stipulated by the multiracial 1997 Constitution impossible. Using Allport’s recommendations on mitigating inter-group conflict in divided communities, the thesis proposes a three-pronged approach to inter-group conciliation in Fiji, based on implementing national identity, truth and reconciliation and legislative reforms. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is dedicated to the Indo-Fijians in rural Fiji who suffered physical violence in the aftermath of the May 2000 nationalist coup.