Sustainable Mining Communities Post Mine Closure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Kenneth Kaunda District Municipality Increased from 695 934 in 2011 to 742 822 in 2016

DR KENNETH KAUNDA District NW Page 1 of 35 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. INTRODUCTION: BRIEF OVERVIEW ...................................................................... 5 2.1. Location ................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Historical Perspective............................................................................................................................ 5 2.3. Spatial Status ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2.4. Land Ownership .................................................................................................................................... 6 3. SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT PROFILE ........................................................................ 6 3.1. Key Social Demographics ...................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Population.............................................................................................................................................. 6 3.1.2. Race Gender and Age ............................................................................................................................ 7 3.1.3. Households ........................................................................................................................................... -

Research Healthcare Utilization for Common Infectious Disease Syndromes in Soweto and Klerksdorp, South Africa

Open Access Research Healthcare utilization for common infectious disease syndromes in Soweto and Klerksdorp, South Africa Karen Kai-Lun Wong1,2, Claire von Mollendorf3,4, Neil Martinson5,6, Shane Norris4, Stefano Tempia1,3, Sibongile Walaza3, Ebrahim Variava 4,7, Meredith Lynn McMorrow1,2, Shabir Madhi3,4, Cheryl Cohen3,4,&, Adam Lauren Cohen1,2 1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia USA, 2United States Public Health Service, 3National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 5MRC Developmental Pathways for Health Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 6Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland USA, 7Klerksdorp- Tshepong Hospital Complex, Klerksdorp, South Africa &Corresponding author: Cheryl Cohen, Centre for Respiratory Diseases and Meningitis, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Private Bag X4, Sandringham, 2131, Gauteng, South Africa Key words: Diarrhea, health services, meningitis, respiratory tract infections, South Africa Received: 24/11/2017 - Accepted: 27/12/2017 - Published: 10/08/2018 Abstract Introduction: Understanding healthcare utilization helps characterize access to healthcare, identify barriers and improve surveillance data interpretation. We describe healthcare-seeking behaviors for common infectious syndromes and identify reasons for seeking care. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey among residents in Soweto and Klerksdorp, South Africa. Households were -

Amper Gesond Na Koronavirus

Facebook: 38k + followers DIGITAL Facebook: 130k + post reach FOOTPRINT: www.northwestnewspapers.co.za Oprit wink vir langasem: Klerksdorp 160km vir Member of ABC • Vol 136 Weeke 16 • 125 Ian Street,c Klerksdorp ord liefde R• Tel: 018 464 1911 • Fax: 018 464 2009 • 4 Grace period to renew Amper gesond license na Koronavirus disks “Dit voel soos griep, net baie erger” 3 5 Food relief eff orts underway CSS security is at the frontline of delivering food parcels to the needy in the Kosh Area. A Kosh Covid-19 Disaster Trust Fund was established to help in this time of need. More information, and how to help on p 4. Photo: Facebook, MG Creations. 16-17 APRIL 2020 2 • KLERKSDORP RECORD community news 17 aPRiL 2020 Code of Conduct Publisher Audit This newspaper subscribes to the Code of Ethics and Published by North West Newspapers (Pty) Ltd; The distribution of Conduct for South African Print and Online Media and printed by North West Web Printers (Pty) Ltd this ABC newspaper Klerksdorp that prescribes news that is truthful, accurate, fair a division of CTP Limited, 13 Coetzer Street. All is independently and balanced. If we don’t live up to the Code, within rights and reproduction of all reports, photographs, audited to the 20 days of the date of publication of the material, drawings and all materials published in this professional standards ecord please contact the Public Advocate at 011 484 3612, newspaper are hereby reserved in terms of administrated by the R fax: 011 484 3619. You can also contact our Case Section 12 (7) of the Audit Bureau of Contact us: Offi cer on khanyim@ombudsman. -

OAS to 48748 R10 P/Sms DONATE OAS to 40580 R20 P/Sms

074 306 9811 Facebook : Orkney Animal Shelter OFFICE / ADOPTIONS : 074 306 9811 SMS Line : Email : [email protected] DONATE OAS to 48748 R10 p/sms DONATE OAS to 40580 R20 p/sms AFTER HOURS / EMERGENCIES / c/o Meteor Rd & Leemhuis Ave CRUELTY COMPLAINTS : 076 701 9227 Uraniaville, Klerksdorp Email : [email protected] 2571 March 2021 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN INTRODUCTION We are an independent Non-profit organization that was founded in 2010 by a group of individuals who were concerned about the well-being of the animals in Orkney as there was no SPCA. Our main objective is to rehabilitate and re-home as many of the unwanted and homeless cats and dogs as we can. Our policy is that all our animals are sterilised / castrated before being permanently rehomed, as we are apposed to breeding. In January 2020 the SPCA in Klerksdorp closed due to the lack of funds and aid from the community. The NSPCA approached us to take over the property and their responsibilities and pound duties in the KOSH area. We then relocated from our Anglogold premises next to Westvaal Hospital, Orkney to the old SPCA premises in Klerksdorp. HOW DID THIS EFFECTS OUR OPERATIONS BEFORE AFTER Shelter Pound / Shelter STATUS (Selective animals admission) (Can’t refuse any stray animal) SHELTER CAPACITY 25 dog kennels / 15 cat kennels 72 dog kennels / 32 cat kennels PRESENT HOLDING 65 dogs / 25 cats MONTHLY NEW ARRIVALS Approx. 15 dogs / 7 cats Approx. 55 dogs / 80 cats DAYS SPENT AT SHELTER 60 days Orkney Kanana Vaal Reefs Klerksdorp Jouberton Orkney AREAS THE SHELTER COVER Stilfontein Kanana Khuma Tigane Buffelsfontein Dominionville Hartbeesfontein Bothaville AREAS THE SHELTER ASSIST Vierfontein Vierfontein Leedoringstad CALL OUTS Approx. -

The Geology of the Country Around Potchefstroom and Klerksdorp

r I! I I . i UNION OF SOUTH AFRICA DJ;;~!~RTMENT OF MINES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY THE GEOLOGY OF THE COUNTRY AROUND POTCHEFSTROOM AND KLERKSDORP , An Explanation of Sheet No. 61 (Potchefstroom). BY LOUIS T. NEL, D.Se., F.G.S., F. C. TRUTER, M.A., Ph.D, J. WILLEMSE, Ph.D., incorporating previous observations by E. T. MELLOR, D.Se., F,G.S. Published by Authority of the Honourable the Minister of Mines {COPYRiGHT1 PRINTED IN THE UNION OF SoUTH AFRICA BY THE GOVERNMENT PRINTER. PRETORIA 1939 G.P.-S.4423-1939-1,500. 9 ,ad ;est We are indebted to Western Reefs Exploration and Development Company, Limited, and to the Union Corporation, Limited, who have generously furnished geological information obtained in the red course of their drilling in the country about Klerksdorp. We are also :>7 1 indebted to Dr. p, F. W, Beetz whose presentation of the results of . of drilling carried out by the same company provides valuable additions 'aal to the knowledge of the geology of the district, and to iVIr. A, Frost the for his ready assistance in furnishing us with the results oUhe surveys the and drilling carried out by his company, Through the kind offices ical of Dr. A, L du Toit we were supplied with the production of diamonds 'ing in the area under description which is incorporated in chapter XL lim Other sources of information or assistance given are specifically ers acknowledged at appropriate places in this report. (LT,N.) the gist It-THE AREA AND ITS PHYSICAL FEATURES, ond The area described here is one of 2,128 square miles and extends )rs, from latitude 26° 30' to 27° south and from longtitude 26° 30' to the 27° 30' east. -

2019 Blood Sweat and Tears Extractives

BLOOD, SWEAT, AND TEARS: COMMUNITY REDRESS STRATEGIES AND THEIR EFFECTIVENESS IN MITIGATING THE IMPACTS OF EXTRACTIVES AND RELATED INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS IN SOUTH AFRICA: 2008–2018 | 1 2 CONTENTS PREFACE List of Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Acknowledgements 7 Summary and Conclusions 9 Key Findings and Recommendations 11 CHAPTER ONE 1. Background to the Study 15 1.1. Introduction 16 1.2. Background to South Africa (Country Analysis) 16 1.3. Statement of the Problem 18 1.4. Research Objectives 20 1.5. Literature Review 21 CHAPTER TWO 2. The Legislative Architecture of the MPRDA 23 2.1. Analysis of SA Mining Environmental Legislation 24 2.2. Regulatory Governance Framework Undermined 28 CHAPTER THREE 3. Impacts 41 3.1. Water 46 3.2. Air pollution 47 3.3. Dust Pollution 47 3.4. Health and well-being of communities 48 3.5. Socio-Economic Impacts 49 3.6. Illegitimate/Illegal Business Operations 50 3.7. Grave Sites 50 CHAPTER FOUR 4. Strategic Interventions 51 4.1. Mitigating Mining Impacts 52 4.2. Barriers Restricting Effective Implementation of Strategies Addressing Negative 70 Impacts Associated with Mining References 78 Appendices 82 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS/ ACRONYMS ACC Amadiba Crisis Committee AECA Australia’s Export Credit Agency AMD Acid Mine Drainage AMI Alternative Mining Indaba BBKTA Bakgatla Ba Kgafela Traditional Administration CALS Centre for Applied Legal Studies CBOs Community-based Organisations CER Centre for Environmental Rights CSR Corporate Social Responsibility CWP Coal Workers’ Pneumoconiosis DEA Department of Environmental -

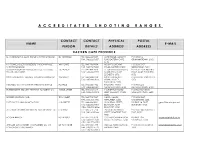

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

MATLOSANA City on the Move?

[Type text] MATLOSANA City on the Move? SACN Programme: Secondary Cities Document Type: SACN Report Paper Document Status: Final Date: 10 April 2014 Joburg Metro Building, 16th floor, 158 Loveday Street, Braamfontein 2017 Tel: +27 (0)11-407-6471 | Fax: +27 (0)11-403-5230 | email: [email protected] | www.sacities.net 1 [Type text] CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Historical perspective 3 3. Current status and planning 6 3.1 Demographic and population change 6 3.2 Social issues 12 3.3 Economic analysis 16 3.3.1 Economic profile 17 3.3.2 Business overview 26 3.3.3 Business / local government relations 31 3.4 Municipal governance and management 33 3.5 Overview of Integrated Development Planning (IDP) 34 3.6 Overview of Local Economic Development (LED) 39 3.7 Municipal finance 41 3.7.1 Auditor General’s Report 42 3.7.2 Income 43 3.7.3 Expenditure 46 3.8 Spatial planning 46 3.9 Municipal services 52 3.9.1 Housing 52 3.9.2 Drinking and Waste Water 54 3.9.3 Electricity 58 4. Natural resources and the environment 60 5. Innovation, knowledge economy and human capital formation 60 5.1 Profile of existing research 63 6. Synthesis 65 ANNEXURES 67 ANNEXURE 1: Revenue sources for the City of Matlosana Local Municipality R’000 (2006/7–2012/13) 67 i [Type text] LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Position of the City of Matlosana Local Municipality in relation to the rest of the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 1 Figure 2: Population and household growth for the City of Matlosana (1996–2011) .................................. -

2021 BROCHURE the LONG LOOK the Pioneer Way of Doing Business

2021 BROCHURE THE LONG LOOK The Pioneer way of doing business We are an international company with a unique combination of cultures, languages and experiences. Our technologies and business environment have changed dramatically since Henry A. Wallace first founded the Hi-Bred Corn Company in 1926. This Long Look business philosophy – our attitude toward research, production and marketing, and the worldwide network of Pioneer employees – will always remain true to the four simple statements which have guided us since our early years: We strive to produce the best products in the market. We deal honestly and fairly with our employees, sales representatives, business associates, customers and stockholders. We aggressively market our products without misrepresentation. We provide helpful management information to assist customers in making optimum profits from our products. MADE TO GROW™ Farming is becoming increasingly more complex and the stakes ever higher. Managing a farm is one of the most challenging and critical businesses on earth. Each day, farmers have to make decisions and take risks that impact their immediate and future profitability and growth. For those who want to collaborate to push as hard as they can, we are strivers too. Drawing on our deep heritage of innovation and breadth of farming knowledge, we spark radical and transformative new thinking. And we bring everything you need — the high performing seed, the advanced technology and business services — to make these ideas reality. We are hungry for your success and ours. With us, you will be equipped to ride the wave of changing trends and extract all possible value from your farm — to grow now and for the future. -

Related Murder Warning

05 June 2015, PLATINUM KOSH, Email: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] P03 Warning: Three arrested 5 arrested for stock theft in motorcycle theft on for gang- Hartebeesfontein the increase related murder Hartbeesfontein±7KHSROLFHDUUHVWHG¿YHVXVSHFWVDJHGIURPWRRQ7XHVGD\-XQH 2015 for stock theft in Dominionville, Hartbeesfontein at about 08:00. Rustenburg/ Potchefstroom – The police in Klerksdorp – Three suspects aged 20, 21 and 27 appeared before the Klerks- Capt. Paul Ramaloko, police spokesperson, says the police received a tip-off from members of North West are concerned about the reported dorp Magistrate’s Court on Tuesday, 2 the community about “suspicious people” who were slaughtering cattle in Dominionville. Upon number of motorcycle theft cases when com- June 2015, for a murder and robbery DUULYDODWWKHVFHQHSROLFHIRXQG¿YHVXVSHFWVZKRZHUHEXV\VODXJKWHULQJFDWWOH pared to the same period last year, Col Sabata that took place in Kanana on Sunday, 31 7KHUHZHUH%RQVPDUDFDWWOHLQWRWDO¿YHFDOYHVDQGVL[FRZVZKLFKLQFOXGHVWKHWZRFRZV May at about 15:30. Mokgwabone, provincial police spokesperson that were slaughtered, all to the value of R90 000. Through the help of the brand mark on the Sergeant Kelebogile Moleko, police stock they managed to identify the owner. The police immediately arrested the suspects. said. “This crime is prevalent in Potchefstroom spokesperson, says the police were con- Ramaloko says it is alleged that the cattle were stolen from a Klippan farm approximately 8km WDFWHGDERXWDJDQJ¿JKWLQ([WHQVLRQ and Rustenburg, and committed mostly in resi- from the crime scene. The police also recovered suspected stolen copper cable with an esti- dential areas.” Kanana. Upon arrival they discovered a dead person in a pool of blood with mul- mated value of R2 000 on the scene. -

Groundwater and Surface Water) Quality and Management in the North-West Province, South Africa

A scoping study on the environmental water (groundwater and surface water) quality and management in the North-West Province, South Africa Report to the WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION by CC Bezuidenhout and the North-West University Team WRC Report No. KV 278/11 ISBN No 978-1-4312-0174-7 October 2011 The publication of this report emanates from a WRC project titled A scoping study on the environmental water (groundwater and surface water) quality and management in the north- West Province, south Africa (WRC Project No. K8/853) DISCLAIMER This report has been reviewed by the Water Research Commission (WRC) and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BACKGROUND & RATIONALE Water in the North West Province is obtained from ground and surface water sources. The latter are mostly non-perennial and include rivers and inland lakes and pans. Groundwater is thus a major source and is used for domestic, agriculture and mining purposes mostly without prior treatment. Furthermore, there are several pollution impacts (nitrates, organics, microbiological) that are recognised but are not always addressed. Elevated levels of inorganic substances could be due to natural geology of areas but may also be due to pollution. On the other hand, elevated organic substances are generally due to pollution from sanitation practices, mining activities and agriculture. Water quality data are, however, fragmented. A large section of the population of the North West Province is found in rural settings and most of them are affected by poverty. -

Annexure A: Municipalities Affected by Withholding of Local Government

Annexure A Municipalities affected by withholding of the local government equitable share due to persistent non-payment of creditors March tranche of Equitable Share released to the following municipalities as at 16 April 2015 WC012 CEDERBERG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY DC29 ILEMBE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY FS162 KOPANONG MUNICIPALITY EC104 MAKANA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY LIM344 MAKHADO LOCAL MUNICIPALITY MP322 MBOMBELA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY FS204 METSIMAHOLO LOCAL MUNICIPALITY (including Deneysville) DC33 MOPANI DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY NW392 NALEDI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY DC38 NGAKA MODIRI MOLEMA DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY FS193 NKETOANA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY EC128 NXUBA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY FS195 PHUMELELA MUNICIPALITY FS182 TOKOLOGO LOCAL MUNICIPALITY Municipalities that still have to meet the requirements set by National Treasury LIM334 BA-PHALABORWA MUNICIPALITY MP325 BUSHBUCKRIDGE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NW403 CITY OF MATLOSANA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY FS192 DIHLABENG MUNICIPALITY NC092 DIKGATLONG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NW384 DITSOBOTLA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY (including Lichtenburg) DC39 DR RUTH S. MOMPATI DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY MP314 EMAKHAZENI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY MP312 EMALAHLENI LOCAL MUNICIPALITY MP307 GOVAN MBEKI MUNICIPALITY NC064 KAMIESBERG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NW374 KGETLENGRIVIER LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NC067 KHAI-MA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NW396 LEKWA - TEEMANE MP305 LEKWA LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NW372 MADIBENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY NW383 MAFIKENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY FS161 MAFUBE MUNICIPALITY NC093 MAGARENG MUNICIPALITY EC143 MALETSWAI MUNICIPALITY FS205 MALUTI A PHOFUNG MUNICIPALITY NW393 MAMUSA LOCAL