2019 Blood Sweat and Tears Extractives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Healthcare Utilization for Common Infectious Disease Syndromes in Soweto and Klerksdorp, South Africa

Open Access Research Healthcare utilization for common infectious disease syndromes in Soweto and Klerksdorp, South Africa Karen Kai-Lun Wong1,2, Claire von Mollendorf3,4, Neil Martinson5,6, Shane Norris4, Stefano Tempia1,3, Sibongile Walaza3, Ebrahim Variava 4,7, Meredith Lynn McMorrow1,2, Shabir Madhi3,4, Cheryl Cohen3,4,&, Adam Lauren Cohen1,2 1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia USA, 2United States Public Health Service, 3National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa, 4University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 5MRC Developmental Pathways for Health Research Unit, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 6Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland USA, 7Klerksdorp- Tshepong Hospital Complex, Klerksdorp, South Africa &Corresponding author: Cheryl Cohen, Centre for Respiratory Diseases and Meningitis, National Institute for Communicable Diseases, Private Bag X4, Sandringham, 2131, Gauteng, South Africa Key words: Diarrhea, health services, meningitis, respiratory tract infections, South Africa Received: 24/11/2017 - Accepted: 27/12/2017 - Published: 10/08/2018 Abstract Introduction: Understanding healthcare utilization helps characterize access to healthcare, identify barriers and improve surveillance data interpretation. We describe healthcare-seeking behaviors for common infectious syndromes and identify reasons for seeking care. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional survey among residents in Soweto and Klerksdorp, South Africa. Households were -

Amper Gesond Na Koronavirus

Facebook: 38k + followers DIGITAL Facebook: 130k + post reach FOOTPRINT: www.northwestnewspapers.co.za Oprit wink vir langasem: Klerksdorp 160km vir Member of ABC • Vol 136 Weeke 16 • 125 Ian Street,c Klerksdorp ord liefde R• Tel: 018 464 1911 • Fax: 018 464 2009 • 4 Grace period to renew Amper gesond license na Koronavirus disks “Dit voel soos griep, net baie erger” 3 5 Food relief eff orts underway CSS security is at the frontline of delivering food parcels to the needy in the Kosh Area. A Kosh Covid-19 Disaster Trust Fund was established to help in this time of need. More information, and how to help on p 4. Photo: Facebook, MG Creations. 16-17 APRIL 2020 2 • KLERKSDORP RECORD community news 17 aPRiL 2020 Code of Conduct Publisher Audit This newspaper subscribes to the Code of Ethics and Published by North West Newspapers (Pty) Ltd; The distribution of Conduct for South African Print and Online Media and printed by North West Web Printers (Pty) Ltd this ABC newspaper Klerksdorp that prescribes news that is truthful, accurate, fair a division of CTP Limited, 13 Coetzer Street. All is independently and balanced. If we don’t live up to the Code, within rights and reproduction of all reports, photographs, audited to the 20 days of the date of publication of the material, drawings and all materials published in this professional standards ecord please contact the Public Advocate at 011 484 3612, newspaper are hereby reserved in terms of administrated by the R fax: 011 484 3619. You can also contact our Case Section 12 (7) of the Audit Bureau of Contact us: Offi cer on khanyim@ombudsman. -

OAS to 48748 R10 P/Sms DONATE OAS to 40580 R20 P/Sms

074 306 9811 Facebook : Orkney Animal Shelter OFFICE / ADOPTIONS : 074 306 9811 SMS Line : Email : [email protected] DONATE OAS to 48748 R10 p/sms DONATE OAS to 40580 R20 p/sms AFTER HOURS / EMERGENCIES / c/o Meteor Rd & Leemhuis Ave CRUELTY COMPLAINTS : 076 701 9227 Uraniaville, Klerksdorp Email : [email protected] 2571 March 2021 TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN INTRODUCTION We are an independent Non-profit organization that was founded in 2010 by a group of individuals who were concerned about the well-being of the animals in Orkney as there was no SPCA. Our main objective is to rehabilitate and re-home as many of the unwanted and homeless cats and dogs as we can. Our policy is that all our animals are sterilised / castrated before being permanently rehomed, as we are apposed to breeding. In January 2020 the SPCA in Klerksdorp closed due to the lack of funds and aid from the community. The NSPCA approached us to take over the property and their responsibilities and pound duties in the KOSH area. We then relocated from our Anglogold premises next to Westvaal Hospital, Orkney to the old SPCA premises in Klerksdorp. HOW DID THIS EFFECTS OUR OPERATIONS BEFORE AFTER Shelter Pound / Shelter STATUS (Selective animals admission) (Can’t refuse any stray animal) SHELTER CAPACITY 25 dog kennels / 15 cat kennels 72 dog kennels / 32 cat kennels PRESENT HOLDING 65 dogs / 25 cats MONTHLY NEW ARRIVALS Approx. 15 dogs / 7 cats Approx. 55 dogs / 80 cats DAYS SPENT AT SHELTER 60 days Orkney Kanana Vaal Reefs Klerksdorp Jouberton Orkney AREAS THE SHELTER COVER Stilfontein Kanana Khuma Tigane Buffelsfontein Dominionville Hartbeesfontein Bothaville AREAS THE SHELTER ASSIST Vierfontein Vierfontein Leedoringstad CALL OUTS Approx. -

MATLOSANA City on the Move?

[Type text] MATLOSANA City on the Move? SACN Programme: Secondary Cities Document Type: SACN Report Paper Document Status: Final Date: 10 April 2014 Joburg Metro Building, 16th floor, 158 Loveday Street, Braamfontein 2017 Tel: +27 (0)11-407-6471 | Fax: +27 (0)11-403-5230 | email: [email protected] | www.sacities.net 1 [Type text] CONTENTS 1. Introduction 1 2. Historical perspective 3 3. Current status and planning 6 3.1 Demographic and population change 6 3.2 Social issues 12 3.3 Economic analysis 16 3.3.1 Economic profile 17 3.3.2 Business overview 26 3.3.3 Business / local government relations 31 3.4 Municipal governance and management 33 3.5 Overview of Integrated Development Planning (IDP) 34 3.6 Overview of Local Economic Development (LED) 39 3.7 Municipal finance 41 3.7.1 Auditor General’s Report 42 3.7.2 Income 43 3.7.3 Expenditure 46 3.8 Spatial planning 46 3.9 Municipal services 52 3.9.1 Housing 52 3.9.2 Drinking and Waste Water 54 3.9.3 Electricity 58 4. Natural resources and the environment 60 5. Innovation, knowledge economy and human capital formation 60 5.1 Profile of existing research 63 6. Synthesis 65 ANNEXURES 67 ANNEXURE 1: Revenue sources for the City of Matlosana Local Municipality R’000 (2006/7–2012/13) 67 i [Type text] LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Position of the City of Matlosana Local Municipality in relation to the rest of the Dr Kenneth Kaunda District Municipality .......................................................................................................................... 1 Figure 2: Population and household growth for the City of Matlosana (1996–2011) .................................. -

Related Murder Warning

05 June 2015, PLATINUM KOSH, Email: [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] P03 Warning: Three arrested 5 arrested for stock theft in motorcycle theft on for gang- Hartebeesfontein the increase related murder Hartbeesfontein±7KHSROLFHDUUHVWHG¿YHVXVSHFWVDJHGIURPWRRQ7XHVGD\-XQH 2015 for stock theft in Dominionville, Hartbeesfontein at about 08:00. Rustenburg/ Potchefstroom – The police in Klerksdorp – Three suspects aged 20, 21 and 27 appeared before the Klerks- Capt. Paul Ramaloko, police spokesperson, says the police received a tip-off from members of North West are concerned about the reported dorp Magistrate’s Court on Tuesday, 2 the community about “suspicious people” who were slaughtering cattle in Dominionville. Upon number of motorcycle theft cases when com- June 2015, for a murder and robbery DUULYDODWWKHVFHQHSROLFHIRXQG¿YHVXVSHFWVZKRZHUHEXV\VODXJKWHULQJFDWWOH pared to the same period last year, Col Sabata that took place in Kanana on Sunday, 31 7KHUHZHUH%RQVPDUDFDWWOHLQWRWDO¿YHFDOYHVDQGVL[FRZVZKLFKLQFOXGHVWKHWZRFRZV May at about 15:30. Mokgwabone, provincial police spokesperson that were slaughtered, all to the value of R90 000. Through the help of the brand mark on the Sergeant Kelebogile Moleko, police stock they managed to identify the owner. The police immediately arrested the suspects. said. “This crime is prevalent in Potchefstroom spokesperson, says the police were con- Ramaloko says it is alleged that the cattle were stolen from a Klippan farm approximately 8km WDFWHGDERXWDJDQJ¿JKWLQ([WHQVLRQ and Rustenburg, and committed mostly in resi- from the crime scene. The police also recovered suspected stolen copper cable with an esti- dential areas.” Kanana. Upon arrival they discovered a dead person in a pool of blood with mul- mated value of R2 000 on the scene. -

Humusica 2, Article 16: Techno Humus Systems and Recycling of Waste

Humusica 2, article 16: Techno humus systems and recycling of waste Augusto Zanella, Jean-François Ponge, Stefano Guercini, Clelia Rumor, François Nold, Paolo Sambo, Valentina Gobbi, Claudia Schimmer, Catherine Chaabane, Marie-Laure Mouchard, et al. To cite this version: Augusto Zanella, Jean-François Ponge, Stefano Guercini, Clelia Rumor, François Nold, et al.. Humu- sica 2, article 16: Techno humus systems and recycling of waste. Applied Soil Ecology, Elsevier, 2018, 122 (Part 2), pp.220 - 236. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.09.037. hal-01668155 HAL Id: hal-01668155 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01668155 Submitted on 19 Dec 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain 1 Humusica 2, article 16: Techno humus systems and recycling of waste Augusto Zanellaa*, Jean-François Pongeb, Stefano Guercinia, Clelia Rumora, François Noldc, Paolo Samboa, Valentina Gobbia, Claudia Schimmerd, Catherine Chaabanec, Marie-Laure Mouchardc, Elena Garciac, Piet van Deventerd a University of Padua, Italy b Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France c Mairie de Paris, Laboratoire d’Agronomie, France d Northwest University, Potchefstroom, South Africa ABSTRACT Techno humus systems correspond to man-made topsoils under prominent man influence. -

Worldwide Soaring Turnpoint Exchange Unofficial

Worldwide Soaring Turnpoint Exchange Unofficial Coordinates for the Potchefstroom, South Africa Control Points Contest: South African Nationals, 2021 - 15m, 2 Seater and Club Class Courtesy of Oscar Goudriaan via Richard Glennie Dated: 20 September 2021 Magnetic Variation: 18.4W Printed Tuesday,21September 2021 at 13:44 GMT UNOFFICIAL, USE ATYOUR OWN RISK Do not use for navigation, for flight verification only. Always consult the relevant publications for current and correct information. This service is provided free of charge with no warrantees, expressed or implied. User assumes all risk of use. Number Name Latitude Longitude Latitude Longitude Elevation Codes* Comment Distance Bearing °’" °’" °’ °’ FEET Km 1Welkom 28 00 00 S 26 40 00 E 28 00.000 S 26 40.000 E 4528 AT153 214 2Control North 27 54 11 S 26 42 35 E 27 54.183 S 26 42.583 E 4528 T 141 213 3Control NW 27 54 42 S 26 36 00 E 27 54.700 S 26 36.000 E 4350 T Road Junction 146 217 4Welkom Start 27 59 46 S 26 32 41 E 27 59.767 S 26 32.683 E 4528 T 156 218 5Control South 28 06 32 S 26 42 58 E 28 06.533 S 26 42.967 E 4528 T 164 211 10 Riebeeckstad 27 54 58 S 26 47 35 E 27 54.967 S 26 47.583 E 4528 T 141 210 11 Odendaalsrus 27 51 10 S 26 44 06 E 27 51.167 S 26 44.100 E 4524 T 135 213 12 Virginia 28 07 44 S 26 53 36 E 28 07.733 S 26 53.600 E 4524 T 163 205 13 Allanridge 27 45 18 S 26 39 18 E 27 45.300 S 26 39.300 E 4528 T 127 218 14 Beatrix 28 14 01 S 26 46 01 E 28 14.017 S 26 46.017 E 4524 T 176 208 15 Welgelee 28 12 40 S 26 49 10 E 28 12.667 S 26 49.167 E 4524 T 173 207 16 Kalkvlakte -

Recueil Des Colis Postaux En Ligne SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE

Recueil des colis postaux en ligne ZA - South Africa SOUTH AFRICA POST OFFICE LIMITED ZAA Service de base RESDES Informations sur la réception des Oui V 1.1 dépêches (réponse à un message 1 Limite de poids maximale PREDES) (poste de destination) 1.1 Colis de surface (kg) 30 5.1.5 Prêt à commencer à transmettre des Oui données aux partenaires qui le veulent 1.2 Colis-avion (kg) 30 5.1.6 Autres données transmis 2 Dimensions maximales admises PRECON Préavis d'expédition d'un envoi Oui 2.1 Colis de surface international (poste d'origine) 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non RESCON Réponse à un message PRECON Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus (poste de destination) grand pourtour) CARDIT Documents de transport international Oui 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non pour le transporteur (poste d'origine) (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus RESDIT Réponse à un message CARDIT (poste Oui grand pourtour) de destination) 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui 6 Distribution à domicile (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus grand pourtour) 6.1 Première tentative de distribution Oui 2.2 Colis-avion effectuée à l'adresse physique du destinataire 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m Non 6.2 En cas d'échec, un avis de passage est Oui (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus laissé au destinataire grand pourtour) 6.3 Destinataire peut payer les taxes ou Non 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Non droits dus et prendre physiquement (ou 3m somme de la longueur et du plus livraison de l'envoi grand pourtour) 6.4 Il y a des restrictions gouvernementales 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m Oui ou légales vous limitent dans la (ou 2m somme de la longueur et du plus prestation du service de livraison à grand pourtour) domicile. -

Copy of Privately Owned Dams

Capacity No of dam Name of dam Town nearest Province (1000 m³) A211/40 ASH TAILINGS DAM NO.2 MODDERFONTEIN GT 80 A211/41 ASH TAILINGS DAM NO.5 MODDERFONTEIN GT 68 A211/42 KNOPJESLAAGTE DAM 3 VERWOERDBURG GT 142 A211/43 NORTH DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 245 A211/44 SOUTH DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 124 A211/45 MOOIPLAAS SLIK DAM ERASMIA PRETORIA GT 281 A211/46 OLIFANTSPRUIT-ONDERSTE DAM OLIFANTSFONTEIN GT 220 A211/47 OLIFANTSPRUIT-BOONSTE DAM OLIFANTSFONTEIN NW 450 A211/49 LEWIS VERWOERDBURG GT 69 A211/51 BRAKFONTEIN RESERVOIR CENTURION GT 423 A211/52 KLIPFONTEIN NO1 RESERVOIR KEMPTON PARK GT 199 A211/53 KLIPFONTEIN NO2 RESERVOIR KEMPTON PARK GT 259 A211/55 ZONKIZIZWE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 150 A211/57 ESKOM CONVENTION CENTRE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 80 A211/59 AALWYNE DAM BAPSFONTEIN GT 132 A211/60 RIETSPRUIT DAM CENTURION GT 51 A211/61 REHABILITATION DAM 1 BIRCHLEIGH NW 2857 A212/40 BRUMA LAKE DAM JOHANNESBURG GT 120 A212/54 JUKSKEI SLIMES DAM HALFWAY HOUSE GT 52 A212/55 KYNOCH KUNSMIS LTD GIPS AFVAL DAM KEMPTON PARK GT 3000 A212/56 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 1 EDENVALE GT 550 A212/57 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO.2 MODDERFONTEIN GT 28 A212/58 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 3 EDENVALE GT 290 A212/59 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO. 4 EDENVALE GT 571 A212/60 MODDERFONTEIN FACTORY DAM NO.5 MODDERFONTEIN GT 30 A212/65 DOORN RANDJIES DAM PRETORIA GT 102 A212/69 DARREN WOOD JOHANNESBURG GT 21 A212/70 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 1 DAINFERN GT 72 A212/71 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 2 DAIRNFERN GT 64 A212/72 ZEVENFONTEIN DAM 3 MiDRAND GT 58 A212/73 BCC DAM AT SECOND JOHANNESBURG GT 39 A212/74 DW6 LEOPARD DAM LANSERIA NW 180 A212/75 RIVERSANDS DAM DIEPSLOOT GT 62 A213/40 WEST RAND CONS. -

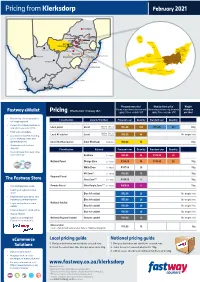

Pricing Fromklerksdorp

Pricing from Klerksdorp February 2021 Polokwane Nelspruit Rustenburg Mahikeng Witbank Pretoria Setlopo Johannesburg Lichtenburg Westonaria Klerksdorp Vaal Coligny Randfontein Randfontein Khutsong Bekkersdal Kuruman Carletonville Suurbekom Welkom Welverdiend Westonaria Newcastle Weldela Harrismith Fochville Sannishof Losberg Richards Bay Agisanang Upington Pietermaritzburg Potchefstroom Bloemfontein Delareyville Hartbeesfontein Lindequesdrif Klerksdorp Stilfontein Khuma Kimberley Ottosdal Dominionville Durban Jouberton Vryburg Port Shepstone Witpoort Wolmaransstad Schweizer Reneke Leeudoringstad Viljoenskroon Makwassie Bothaville East London Knysna Port Elizabeth Cape Town George Plettenberg Bay Mossel Bay Frequent user price* Standard user price* Weight Minimum purchase requirements Minimum purchase requirements allowance Effective from 1 February 2021 Fastway eWallet Pricing apply. Prices exclude VAT apply. Prices exclude VAT per label • Purchasing stock manually is no longer required. Classification Local & Shorthaul Frequent user Quantity Standard user Quantity • Access all Fastway services as AM pick-up - PM delivery and when you need them. Local parcel Local PM pick-up - AM delivery R43.00 100 R75.00 20 30kg • Print your own labels. AM pick-up - PM delivery • A customised portal enabling Local A3 satchel Local PM pick-up - AM delivery R35.00 40 No weight limit you to transact, track and generate reports. Inner Shorthaul parcel Inner Shorthaul (Next day) R60.00 40 30kg • Minimum credit balance required. Classification National Frequent user Quantity Standard user Quantity • Find out more from your sales representative. RedZone (2 - 3 days) R99.00 50 R140.00 20 National Parcel Orange Zone (2 - 3 days) R120.00 50 R150.00 20 15kg White Zone (3 - 4 days) R147.00 20 15kg HV Zone** (2 - 3 days) R99.00 10 15kg Regional Parcel The Fastway Store Grey Zone*** (3 - 5 days) R150.00 5 15kg • Visit fastwaystore.co.za Remote Parcel Ultra Purple Zone *** (5 - 7 days) R400.00 5 10kg • Select your regional online store. -

City of Matlosana

Working for integration North West West Rand Ditsobotla Ventersdorp District Dr Kenneth Municipality Kaunda District Ngaka Modiri Municipality Molema District Municipality Tswaing Tlokwe City Council City of Matlosana N12 Moqhaka Mamusa Fezile Maquassi Dabi District Hills Municipality Lejweleputswa District Dr Ruth Segomotsi Municipality Mompati District Ngwathe Municipality Nala Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA City of Matlosana – North West Housing Market Overview Human Settlements Mining Town Intervention 2008 – 2013 The Housing Development Agency (HDA) Block A, Riviera Office Park, 6 – 10 Riviera Road, Killarney, Johannesburg PO Box 3209, Houghton, South Africa 2041 Tel: +27 11 544 1000 Fax: +27 11 544 1006/7 Acknowledgements The Centre for Affordable Housing Finance (CAHF) in Africa, www.housingfinanceafrica.org Coordinated by Karishma Busgeeth & Johan Minnie for the HDA Disclaimer Reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this report. The information contained herein has been derived from sources believed to be accurate and reliable. The Housing Development Agency does not assume responsibility for any error, omission or opinion contained herein, including but not limited to any decisions made based on the content of this report. © The Housing Development Agency 2015 Contents 1. Frequently Used Acronyms 1 2. Introduction 2 3. Context 5 4. Context: Mining Sector Overview 6 5. Context: Housing 7 6. Context: Market Reports 8 7. Key Findings: Housing Market Overview 9 8. Housing Performance Profile 10 9. Market Size 16 10. Market Activity -

City of Matlosana

CITY OF MATLOSANA 2017-2022 Integrated Development Plan of the City of Matlosana Compiled in terms of Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, 2000 (Act 32 of 2000) DRAFT IDP AMENDMENTS FOR THE 2020/21 FINANCIAL YEAR Integrated Development Plan is a process by which municipalities prepare a 5 – year strategic development plan, which is reviewed annually in consultation with communities and all relevant stakeholders. This development plan serves as the principal strategic instrument which guides all planning, investment, development – and implementation decisions, and coordinates programs and plans across sectors and spheres of government. 1 | P a g e CITY OF MATLOSANA IDP: 2017 – 2022 DRAFT 2020/21 CITY OF MATLOSANA Table of contents Content Page INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 1-6 COMPONENTS: Section A: Executive summary 7 - 11 Section B: Situational analysis IDP process plan 12 - 24 Section C: Situational analysis Ward Based Plans 25 – 121 Vision, mission and Strategic objectives 122 – 127 Section D: Development strategies Spatial analysis & rationale 128 D1: SERVICE DELIVERY & INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT 129 – 131 D2: MUNICIPAL INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT AND TRANSFORMATION 132 – 133 D3: MUNICIPAL FINANCIAL VIABILITY & MANAGEMENT 134- 136 Section E: Projects 137 Draft Capital projects 2020/21 – 2021/22 138 – 145 IDP Unfunded Projects 146 - 153 VTSD Development Plans for Matlosana 154 - 199 2 | P a g e CITY OF MATLOSANA IDP: 2017 – 2022 DRAFT 2020/21 CITY OF MATLOSANA INTRODUCTION 3 | P a g e CITY OF MATLOSANA IDP: 2017 – 2022 DRAFT 2020/21 CITY OF MATLOSANA MUNICIPAL OVERVIEW Geographic Profile The City of Matlosana is situated approximately 164 South West of Johannesburg, on the N12 highway and covers about 3 625km².