Testing Models of English Past-Tense Inflectional Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

I Am an Omnivorous Reader 5975W

“I AM AN OMNIVOROUS READER” Book reviews by CATHERINE COOKE, ALISTAIR DUNCAN, GORDON DYMOWSKI, MATTHEW J ELLIOTT, MARK MOWER, SARAH OBERMULLER-BENNETT, VALERIE SCHREINER, JOHN SHEPPARD, JEAN UPTON, NICHOLAS UTECHIN and ROGER JOHNSON This August and Scholarly Body: The Society at Blaze . If it had a name it’s in the book! 70 edited by Nicholas Utechin; design and layout by For each character we are given the name, story, Heather Owen. The Sherlock Holmes Society of sex, and whether they are alive or dead in the Canon. London , 2021. 116pp. £11.00 (pbk) In addition, depending on the importance of the They say that when drowning, one’s life flashes character, are details which can range from physical before one’s eyes. Reading this book is rather like that appearance to occupation and, if relevant, what — only somewhat drier! While I do not go back to the Holmes deduced about them. Holmes himself has a Society’s foundation in 1951, I do go back over half predictably long entry, whereas, for instance, Captain the Society’s existence and have had much to do with Ferguson (“The Three Gables”) is concisely the 1951 Festival of Britain in Westminster Libraries. described: “A retired sea captain who owned the This is a fitting record, a highly enjoyable read and an house before Mrs Maberley. Holmes asked if there invaluable reference book. There are lists of the was anything about remarkable about him, and if he Presidents, Chairmen and Honorary Members and a had buried something. Mrs Maberley answered in the useful list of all the Society’s publications, so you can negative.” check for any gaps on your shelves that need filling. -

Casting Call

PLACER REPERTORY THEATER Sherlock Holmes: Domestic Mysteries series AUDITIONS For official release: September 28, 2020 AUDITION DUE DATE: Wednesday, October 7, by 5 P.M. Email your resume and a link to your digital materials (.MOV or .MP4 files on Google Drive, YouTube or similar) to [email protected] no later than 5 PM, October 7, 2020. CASTING CALL Placer Repertory Theater seeks actors for four episodes of a digital series on YouTube, Sherlock Holmes: Detective Mysteries Series. These approx. 10-minute episodes are new comedic detective stories inspired by the characters of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Set in the present (2020), the characters of Holmes & Watson are borrowed from the 1890s (The Sign of the Four). The scripts explore the bro-mance, passive-aggression and power/status struggles within domestic relationships while solving a “domestic mystery” from Holmes’ Baker Street domicile. Performance stipend: $40 per episode in which the actor is cast, and a digital copy of the episode. Due to COVID-19, actors rehearse with the full cast via Zoom and shoot in their own home using their own camera (smart phone) in front of a green screen (screen and technical instruction provided). Occasionally, some scenes may be shot in an open, outdoor environment in which each actor is more than six feet from other performers (such as a park). Digital audition requirements • Performance résume • URL (link) to an audition video containing: o Performance of one or more sides (may be read or memorized) ▪ You may audition for more than one character, if desired Digital audition recommendations: (not required) • 1 style monologue (British accent preferred) • Optional accent samples (if you know any of the following accents): o Irish o Scottish o RP o Marked-RP o Estuary English/Cockney DIGITAL AUDITION DATES AUDITION DUE DATE: Wednesday, October 7, by 5 P.M. -

Readings, References and Resources from Confusion 2021

Readings, references and resources from ConFusion 2021 Monday panels and lectures Sherlock Holmes (Ali Baker) Ali Baker (moderator), Aliette de Bodard, David Carlile, Nik Vincent, Fran Dowd The Tea-Master and the Detective, Aliette de Bodard The Case of the Scented Lady, Nik Vincent, in Further Associates of Sherlock Holmes, ed. George Mann Hagar of the Pawn Shop, Fergus Hume Miss Sherlock (TV) – available from Amazon Prime in the UK Doctor Who – DC discussed the Fourth Doctor whose costume at times echoed Holmes’ deerstalker and caped Ulster coat, and the Master as a Moriarty figure Arsene Lupin, the Gentleman Thief, Maurice Leblanc, particularly the stories featuring “Herlock Shomes” The Irregulars (TV) – available from Netflix UK The Adventure of the Speckled Band – Arthur Conan Doyle The Adventure of the Creeping Man – Arthur Conan Doyle The Hound of the Baskervilles – Arthur Conan Doyle Judge Dee (Di Renjie) starting with The Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee (Dee Gong’An),”Buti zhuanren,” trans. Robert van Gulik Madame Vastra from Doctor Who. Big Finish, the audio drama company, has produced stories about Mme Vastra, Jenny and Strax solving supernatural crimes. Sexton Blake, also a Baker St consulting detective The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes with Jeremy Brett as the archetypal Holmes (in my opinion) (TV) – streaming on Britbox Elementary (TV) – we particularly liked the character of Joan Watson – streaming on Amazon Prime Rivals of Sherlock Holmes, collected by Nick Rennison Crowdfunding and the growth of indie games (John Coxon) Ed Fortune, Joss Kl, Kol Ford, John Coxon, Marcus Rowland Jonaya Kemper is an amazing designer, writer and creator! Honestly, back everything they do, buy everything they do: https://www.patreon.com/VioletRiotGames Larpfund makes international larps more accessible to people from all backgrounds. -

Ncam-Casestudy-The Irregulars-V1

Case Study Augmented Reality, My Dear Watson: NVIZ and Ncam Bring The Irregulars ‘Rip’ To Life Sherlock Holmes-inspired Netflix series uses AR, virtual production and real-time camera tracking to tear the world apart ncam-tech.com @ncamtech ncam-technologies-ltd ncamtechnologies ncam_tech 01 AUGMENTED REALITY, MY DEAR WATSON: CASE STUDY NVIZ AND NCAM BRING THE IRREGULARS ‘RIP’ TO LIFE When ‘rip’ is used in a script, it’s regularly a job for the computer graphics team. Sometimes that’s a matter of creating dynamic tears in a costume’s cloth simulation. Other times, it could be slashing the skin of a 3D creature during an epic battle. But what if you’re asked to visualize something as abstract as a rip in the space-time continuum? How about one that needs to have its very own story arc? And what if you need to do all this while collaborating with a tentpole production team during the COVID-19 pandemic? ncam-tech.com @ncamtech ncam-technologies-ltd ncamtechnologies ncam_tech 02 AUGMENTED REALITY, MY DEAR WATSON: CASE STUDY NVIZ AND NCAM BRING THE IRREGULARS ‘RIP’ TO LIFE as framing or camera rigs during principal photography rather there were some scenes looking down at the Rip from above and than having to rely on imagination alone. it looks like a thin membrane. Being able to see the AR version of the shot was important to not just ensure lighting was accurate, “Ncam was very helpful for integrating the Rip into the but also to place the camera at the right angle.” environment the way it was required,” Schmidek says. -

“The Curious Case of Miss Amelia Vernet” by Dana Cameron from Pandora’S Orphans: a Fangborn Collection (DCLE Publishing)

The First Two Pages of “The Curious Case of Miss Amelia Vernet” by Dana Cameron From Pandora’s Orphans: A Fangborn Collection (DCLE Publishing) An Essay by Dana Cameron I had several requirements when I started writing “Miss Amelia Vernet,” and interestingly, that always makes it easier for me, like having to adhere to certain poetic structures. As I had a contract for three short stories set in my Fangborn ’verse, I knew I’d have to feature my vampires, werewolves, and oracles who secretly fight evil to protect humanity. I also knew that this story would have an historical setting; I used short stories about the Fangborn to fill in the history of the Fangborn through time. It was a fun way for me, trained as an archaeologist, to play with history and culture. I settled on late Victorian London (a setting with which I was reasonable comfortable), and I went a step further, setting in the fictional world of Sherlock Holmes, something I’d been exploring in depth at the time. In order to describe life in the rooms of 221B Baker Street to those not familiar with the stories by Arthur Conan-Doyle, I knew I’d need an outsider, someone to help readers learn about Holmes’s adventures. An outsider would also help in describing the Fangborn to those not familiar with my urban fantasy characters. A young person, then, someone who was also Fangborn, learning the ropes about the Family’s secret mission and Holmes’s detective work. It would have been easy to choose a boy—after all, the Baker Street Irregulars all have boys’ names in the Canon—but since the Fangborn have to operate in secret, I thought the added restrictions Victorians placed on young women, especially young “ladies,” would accomplish several things. -

March 2021 Twaddle

INEFFABLE TWADDLE “It is my business to know what other people don’t know.” —The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle Volume 40, Issue 3 March 2021 The monthly publication of The Sound of the Baskervilles A Scion Society of the Baker Street Irregulars since March 31, 1980 Serving the Greater Puget Sound Region of Western Washington, USA Renewal Dues are Now Due Are your dues paid for the April 1, 2021 to March 31, 2022 fiscal year?? If not, now’s the time to act! Send your check—payable to “The Sound of the Baskervilles”—to our Treasurer: Melinda Michaelson P. O. Box 7633 Tacoma, WA 98417 OR if you prefer, go to our website at: www.soundofthebaskervilles.com/Join to pay by PayPal. Rates are: $25 for individuals, $35 for families (U.S. funds only). If you joined in the last 6 months, chances are you paid a lower, prorated rate to join through March 31, 2021, so it’s time for you to renew as well! Thanks! Renewal deadline is March 31! Special Note: Grateful thanks to every Member who added a donation to their renewal dues! SOB Charlie Cook has donated $75, however, to specifically fund renewal dues for five (5) individual Mem- bers who have been unemployed, are suffering from COVID–19 or its residual ailments, or are in dire straits and can’t afford to pay your dues this year! If the Club can help you, please e-mail Secretary Terri or Treasurer Melinda (email addresses are on the back page of this issue of Twaddle)!! March, 2021: The SOBs Relaunch Club Library, now named “Sheila Holtgrieve Memorial Reference Library” Newest Benefit of SOB Membership Arriving Soon! At The SOBs’ September 20, 2020 Meeng, a Member suggested that our Club’s Reference Library be renamed in some fashion to memorialize our former Librarian, SOB Sheila Holtgrieve, who served as our Librarian from June 2010 to June 2018 but passed away on May 1, 2020. -

Irregular Readers Arthur Conan Doyle’S “Six Dirty Scoundrels”, Boyhood and Literacy in Contemporary Sherlockian Children’S Literature

Erica Hateley Irregular Readers Arthur Conan Doyle’s “six dirty scoundrels”, Boyhood and Literacy in Contemporary Sherlockian Children’s Literature Abstract: Young adult (YA) literature is a socialising genre that encourages young readers to take up particular ways of relating to historical or cultural materials. The first decade of the twenty-first century witnessed a boom in Sherlockian YA fiction using the Conan Doyle canon as a context and vocabulary for stories focused on the Baker Street Irregulars as figures of identification. This paper reads YA fiction’s deployment of Conan Doyle’s fictional universe as a strategy for negotiating anxieties of adolescent mas- culinity, particularly in relation to literacy and social agency. Keywords: Young adult literature, detective fiction, masculinity, lit- eracy, adolescence, intertextuality Holmes was Billy’s hero, the man that more than any other in the world he wanted to be like. Holmes’s ability to solve mysteries, using nothing more than his powers of observation and deduction, brought pleas for his help from all over the world. (Pigott-Smith, 18) At the turn of the twentieth century detective stories and their ado- lescent ilk, boys’ magazine literary cultures (and novels such as those later produced by the Stratemeyer Syndicate) were seen as fodder for juvenile delinquency. One significant exception were Arthur Co- nan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, published between 1887 and 1927, but already being endorsed by no less an authority than Robert Baden-Powell in Scouting for Boys (1908). As founder of the scouting movement, Baden-Powell saw the Holmes stories as coherent with a response to delinquency less punitive than didactic: “Discipline is not gained by punishing a child for bad habit, but by substituting a ©2014 E. -

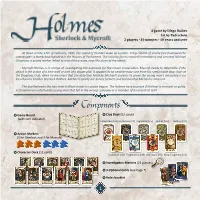

Holmes: Sherlock & Mycroft Rulebook

A game by Diego Ibáñez Art by Pedro Soto 2 players · 30 minutes · 10 years and over At dawn on the 24th of February, 1895, the sound of thunder woke up London. A big column of smoke foreshadowed the catastrophe: a bomb had exploded in the Houses of Parliament. The security forces reacted immediately and arrested Michael Chapman, a young worker linked to anarchist groups, near the place of the attack. Mycroft Holmes is in charge of investigating the explosion for the Crown prosecution. Mycroft needs to determine if the attack is the action of a lone wolf or part of a bigger plot. It appears to be another easy case from his comfortable easy chair at the Diogenes Club, when he discovers that the detective hired by Michael’s parents to prove the young man’s innocence is no less than his brother Sherlock Holmes. Michael’s family are Surrey farmers and believe that Michael is innocent. The duel between the two most brilliant minds in London begins. The Holmes have to prove if Michael is innocent or guilty. Is Chapman an unfortunate young man that fell in the wrong company or a member of an anarchist cell? Components Game Board Clue Deck (52 cards) (with turn indicator) False Pass (×3) Explosive (×4) Cigarette (×5) Bullet (×6) Button (×7) Action Markers (3 for Sherlock and 3 for Mycroft) Character Deck (12 cards) Footprint (×8) Fingerprint (×9) Wildcard (×5) Map Fragment (×5) Investigation Markers (24 glasses) 3 Optional Cards(see Page 7) Rules booklet 1 Preparation of the Game 1 The game board is placed on one side between the players. -

INEFFABLE TWADDLE “It Is My Business to Know What Other People Don’T Know.” —The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle

INEFFABLE TWADDLE “It is my business to know what other people don’t know.” —The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle Volume 39 Issue 5 May, 2020 The monthly publication of The Sound of the Baskervilles A Scion Society of the Baker Street Irregulars since March 31, 1980 Serving the Greater Puget Sound Region of Western Washington, USA 2020 Writing Contest “Sherlock Holmes and the Case of the Uninvited Guest” C J SOB L S !! M Y L : Ms. Lauran Stevens 320 West Roy Street, Apt. 207 Seattle, WA 98119 H C A I Y?! C A, ? J E ? Y C E (2) , : Category 1: In 200 words or less, give us a believable plot and how Holmes will solve it! Category 2: In 200 words or less, introduce the “Uninvited Guest” to us and have him/her/them hook Holmes into taking his/her/their Case! Y N 1 ! F P W P 1 F 2021 B’!!! O , O PRIZES T!!! Sherlock on Screen: Streaming Sherlock With SOB Kris Hambrick Greengs, Friends. Your resident Playacng Busybody here. A few months ago, I came up with the idea of highlighng some of the best, worst, and unheralded performances of our favorite detecve in a monthly column in these pages. Since we are now all honorary members of our own private Diogenes Clubs, and it is not sll 1895, I thought this might be a good me to start by looking at some of the streaming opons available to keep us company. This is by no means exhausve, and there are many more Holmesian offerings out there for rent or purchase through various streaming plaorms. -

Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press 2018

Jan 18 #1 Scuttlebutt from the Spermaceti Press Sherlockians (and Holmesians) gathered in New York to celebrate the Great Detective's 164th birthday during the long weekend from Jan. 10 to Jan. 14. The festivities began with the traditional ASH Wednesday dinner sponsored by The Adventuresses of Sherlock Holmes at Annie Moore's, and continued with the Christopher Morley Walk led by Jim Cox and Dore Nash on Thursday morn- ing (followed by the usual lunch at McSorley's). The Baker Street Irregulars' Distinguished Speaker on Thursday evening was Martin Edwards, the award-winning mystery author and commentator on myster- ies, and then The Baker Street Babes' "Daintiest Scream on the Moor Charity Ball" featured the unveiling of a "Cake Boss" cake in the shape of a bust of Sherlock Holmes (to be featured on an upcoming episode of the TV series. Friday's William Gillette Luncheon included a performance by the Friends of Bogie's at Baker Street, plus Al Gregory's presentation of the annual Jan WHIMSEY Award (named in memory of his wife Jan Stauber), which honors the most whimsical piece in The Serpentine Muse last year, to M.E. Rich. And Otto Penzler's traditional open house at the Mysterious Bookshop provided the usual opportunities to browse and buy. The Irregulars and their guests gathered for the BSI annual dinner at the Yale Club, where Roy Pilot proposed the traditional preprandial first toast to Patricia Izban as The Woman. The annual-dinner agenda included toasts, rituals, and papers, and Mike Whelan (the BSI's "Wiggins") presented this year's Birthday Honours (Irregular Shillings and Investitures) to Shannon Carlisle ("Beacons of the Future!"), Dean Clark ("Watson's Journal"), Denny Dobry ("A Single Large Airy Sitting-Room"), Jeffrey Hatcher ("The Five Or- ange Pips"), Maria Fleischhack ("Rache"), Anastasia Klimchynskaya ("The Old Russian Woman"), Rebecca Romney ("That Gap on That Second Shelf"), Candace Lewis ("A Little Art Jargon"), Nick Martorelli ("Seventeen Steps"), and Al Shaw ("Sir Hugo Baskerville"). -

The Irregular Satellites of Saturn

Denk T., Mottola S., Tosi F., Bottke W. F., and Hamilton D. P. (2018) The irregular satellites of Saturn. In Enceladus and the Icy Moons of Saturn (P. M. Schenk et al., eds.), pp. 409–434. Univ. of Arizona, Tucson, DOI: 10.2458/azu_uapress_9780816537075-ch020. The Irregular Satellites of Saturn Tilmann Denk Freie Universität Berlin Stefano Mottola Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt Federico Tosi Istituto di Astrofsica e Planetologia Spaziali William F. Bottke Southwest Research Institute Douglas P. Hamilton University of Maryland, College Park With 38 known members, the outer or irregular moons constitute the largest group of sat- ellites in the saturnian system. All but exceptionally big Phoebe were discovered between the years 2000 and 2007. Observations from the ground and from near-Earth space constrained the orbits and revealed their approximate sizes (~4 to ~40 km), low visible albedos (likely below ~0.1), and large variety of colors (slightly bluish to medium-reddish). These fndings suggest the existence of satellite dynamical families, indicative of collisional evolution and common progenitors. Observations with the Cassini spacecraft allowed lightcurves to be obtained that helped determine rotational periods, coarse shape models, pole-axis orientations, possible global color variations over their surfaces, and other basic properties of the irregulars. Among the 25 measured moons, the fastest period is 5.45 h. This is much slower than the disruption rotation barrier of asteroids, indicating that the outer moons may have rather low densities, possibly as low as comets. Likely non-random correlations were found between the ranges to Saturn, orbit directions, object sizes, and rotation periods.