Tracking the Great Detective: an Exploration of the Possibility and Value of Contemporary Sherlock Holmes Narratives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beekeepers Apprentice: Or, on the Segregation of the Queen Free

FREE THE BEEKEEPERS APPRENTICE: OR, ON THE SEGREGATION OF THE QUEEN PDF Laurie R King | 356 pages | 27 May 2014 | Picador USA | 9781250055705 | English | United States The Beekeeper's Apprentice, or, on the Segregation of the Queen Summary & Study Guide Audible Premium Plus. Cancel anytime. It is and Mary Russell - Sherlock Holmes's brilliant apprentice, now an Oxford graduate with a degree in theology - is on the verge of acquiring a sizable inheritance. Independent at last, with a passion for divinity and detective work, her most baffling mystery may now involve Holmes and the burgeoning of a deeper affection between herself and the retired detective. By: Laurie R. The third book in the Mary Russell—Sherlock Holmes series. It is Mary Russell Holmes and her husband, the retired Sherlock Holmes, are enjoying the summer together on their Sussex estate when they The Beekeepers Apprentice: Or visited by an old friend, Miss Dorothy Ruskin, an archeologist just returned from Palestine. In the eerie wasteland of Dartmoor, Sherlock Holmes summons his devoted wife and partner, Mary Russell, from her studies at Oxford to aid the investigation of a death and some disturbing phenomena of a decidedly supernatural origin. Through the mists of the moor there have been sightings of a spectral coach made of bones carrying a woman long-ago accused of murdering her husband - and of a hound with a single glowing eye. Coming out of retirement, an aging Sherlock Holmes travels to Palestine with his year-old partner, Mary Russell. There, disguised as ragged Bedouins, they embark on a dangerous mission. -

His Last Bow an Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes

His Last Bow An Epilogue of Sherlock Holmes Arthur Conan Doyle This text is provided to you “as-is” without any warranty. No warranties of any kind, expressed or implied, are made to you as to the text or any medium it may be on, including but not limited to warranties of merchantablity or fitness for a particular purpose. This text was formatted from various free ASCII and HTML variants. See http://sherlock-holm.esfor an electronic form of this text and additional information about it. This text comes from the collection’s version 3.1. t was nine o’clock at night upon the sec- Then one comes suddenly upon something very ond of August—the most terrible August hard, and you know that you have reached the in the history of the world. One might limit and must adapt yourself to the fact. They I have thought already that God’s curse have, for example, their insular conventions which hung heavy over a degenerate world, for there was simply must be observed.” an awesome hush and a feeling of vague expectancy “Meaning ‘good form’ and that sort of thing?” in the sultry and stagnant air. The sun had long Von Bork sighed as one who had suffered much. set, but one blood-red gash like an open wound lay low in the distant west. Above, the stars were shin- “Meaning British prejudice in all its queer man- ing brightly, and below, the lights of the shipping ifestations. As an example I may quote one of my glimmered in the bay. -

20 Chapter Source Notes

20. Saul Among The Prophets 1. pages 375-377. Atlantic City, New Jersey...finally contacted him. Our recreation was composited from several accounts including Harry Houdini, A Magician Among The Spirits (New York : Arno Press, 1972), 149-158; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Edge Of The Unknown (New York : G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1930), 33-36; and “Editorial Notes” by Houdini, MUM, May, 1923, p.165. 2. page 379. Arthur Conan Doyle was born.... Details on Conan Doyle’s early life as it relates to spiritualism can be found in Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England: The Aquarian Press, 1989) and Bernard M.L. Ernst and Hereward Carrington, Houdini And Conan Doyle (New York : Albert and Charles Boni, Inc., 1932). 3. page 379. “showed me at last…” Doyle 1887 letter to spiritualist journal Light, cited in “The Man Who Believed In Fairies”, by Tom Huntington, Smithsonian, clipping in the archives of James Randi. 4. page 379. Lord Kitchener... Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England: The Aquarian Press, 1989), 110. 5. page 379. It was his book...knighthood in 1902. Ibid, 95. 6. page 379. revived him when...collaboration between the two men. “Conan Doyle’s Collaborator”, The Washington Post, April 10, 1902. 7. page 380. died after a long bout of tuberculosis... Kelvin I. Jones, Conan Doyle And The Spirits (England : The Aquarian Press, 1989), 100. 8. page 380. married Jean Leckie... Ibid. 9. page 380. Jean’s friend Lily Loder-Symonds... Ibid, 110-112. 10. page 380. “Where were they?…signals.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The New Revelation, 1917, 10-11. -

His Last Bow Online

NPa3J (Mobile pdf) His Last Bow Online [NPa3J.ebook] His Last Bow Pdf Free Arthur Conan Doyle ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook 2016-04-11 2016-04-11File Name: B01E4S1688 | File size: 33.Mb Arthur Conan Doyle : His Last Bow before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised His Last Bow: His Last Bow: Some Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes is a collection of seven previously-published Sherlock Holmes stories by Arthur Conan Doyle. Five of the stories were published in The Strand Magazine between September 1908 and December 1913. The final story, an epilogue about Holmes' war service, was first published in Collier's on 22 September 1917mdash;one month before the book's premier on 22 October. Some later editions of the collection include "The Adventure of the Cardboard Box", which was also collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1894). The Strand published "The Adventure of Wistaria Lodge" as "A Reminiscence of Sherlock Holmes", and divided it into two parts, called "The Singular Experience of Mr. John Scott Eccles" and "The Tiger of San Pedro". Later printings of His Last Bow correct Wistaria to Wisteria. Also, the first US edition adjusts the subtitle to Some Later Reminiscences of Sherlock Holmes. All editions contain a brief preface, by "John H. Watson, M.D.". The preface assures readers that as of the date of publication (1917), Holmes is long retired from his profession of detectivemdash;but is still alive and well, albeit suffering from a touch of rheumatism. -

The Great Mystery of Life Beyond Death

THE GREAT MYSTERY OF LIFE BEYOND DEATH As dictated by a Spirit TO DIWAN BAHADUR HIRALAL L. KAJI INDIAN EDUCATIONAL SERVICE. BOMBAY. NEW BOOK COMPANY KITAB MAHAL. HORNBY ROAD BOMBAY 1938 Published by P» DirvjV.aw for the New Boob Company. KHnb Vabsb H orn by Road. Fort. Bombay t»nd Printed lit T c t f Printing 31. Tribhovan Road. Bombay 4, PREFACE No pleasure could be greater than the one I experience in presenting this volume to the public, in as much as I was given the unique privilege of expounding the Great Mystery of Life beyond Death as unfolded by the spirit o f the famous spiritualist, the late Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. I wish to state with all the clearness and sincerity at my command that no single idea expressed in this book is mine and that no single sentence as recorded is mine either. Beyond touching up some loose expressions here and there, the book is presented as spelt out letter by letter on the Ouija Board by the late Sir Arthur through my son Mr. Ashok H. Kaji and my nephew Mr. Subodh B. Kaji. I may as well confess that I have not read hitherto any book on spiritualism, nor have I read any religious, philosophical or metaphysical books of the Hindus or any other nation for the matter of that. M y son is a B. Sc. o f the Bombay University and my nephew is an M. Com. of the same University, and neither of them has devoted any thought whatsoever to the problems of the spirit-world, and the life beyond death, for as they have repeatedly declared, it is enough if they concentrated on THE GREAT MYSTERY OF LIFE BEYOND DEATH the problems o f the life before them in this world of the living instead of dabbling in those of the life in the world of the dead, which might well have an interest for people in the evening of life. -

Masculinities in American Psycho and Darkly Dreaming Dexter

Humanities and Social Sciences Review, CD-ROM. ISSN: 2165-6258 :: 08(02):519–534 (2018) FROM TOXIC TO POLITICALLY CORRECT: MASCULINITIES IN AMERICAN PSYCHO AND DARKLY DREAMING DEXTER Petra Fišerová Masaryk University, Czech Republic American Psycho (1991) and Darkly Dreaming Dexter (2004) are two American novels known for having serial killers for protagonists. The gender performances of these two self-proclaimed psychopaths, however, could not be more different; one brings traditional portrayals of violent masculinity to extremes, while the other invents a new take on fictional masculinity. With his desire to punish women, desperation to one-up other men, and frequent attacks of gay panic, American Psycho ’s protagonist Patrick Bateman presents the worst extreme of hegemonic masculinity (as discussed by Connell, O’Neil and others). Driven by his fragile nerves and an even more fragile ego, Patrick often loses control and kills innocent people, his violence all the more heinous and sexualized if the target is a woman. The protagonist of the Dexter series , on the other hand, is an asexual man who has no interest in sexualized violence. Self-possessed, cool-headed, and rational, he knows how to control his bloodlust and channel it productively by hunting other murderers. In pretending to be unremarkable, he positions himself as a submissive man, yet his ego is never threatened by women or other men. Jeff Lindsay’s Dexter Morgan is proof that you can successfully write about a monstrous serial killer in a genre based on hypermasculine tropes without having your protagonist perpetuate the ideals of hegemonic masculinity. Keywords: Hegemonic Masculinity, Counterhegemonic, Control, Crime Literature. -

The Syntheist Movement and Creating God in the Internet Age

1 I Sing the Body Electric: The Syntheist Movement and Creating God in the Internet Age Melodi H. Dincer Senior Thesis Brown University Department of Religious Studies Adviser: Paul Nahme Second Reader: Daniel Vaca Providence, Rhode Island April 15, 20 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgments. 3 Introduction: Making the Internet Holy. .4 Chapter (1) A Technophilic Genealogy: Piracy and Syntheism as Cybernetic Offspring. .12 Chapter (2) The Atheist Theology of Syntheism . 49 Chapter (3) Enacted Syntheisms: An Ethics of Active Virtuality and Virtual Activity. 96 (In)Conclusions. 138 Works Cited. 144 3 Acknowledgments I would briefly like to thank anyone who has had a hand—actually, even the slightest brush of a finger in making this project materialize outside of the confines of my own brain matter. I would first like to thank Kerri Heffernan and my Royce Fellowship cohort for supporting my initial research on the Church of Kopimism. My time in Berlin and Stockholm on behalf of the Royce made an indelible mark on my entire academic career thus far, without which this thesis would definitely not be as out-of-the-box as it is proud to be. I would also like to thank a few professors in the Religious Studies department who, whether they were aware of it or not, encouraged my confidence in this area of study and shaped how I approached the religious communities this project concerns. Specifically, thank you to Prof. Denzey-Lewis, who taught my first religious studies course at Brown and graciously sponsored my Royce research amidst her own travels. Also, infinite thanks and blessings to Fannie Bialek, who so deftly modeled all that is good in this discipline, and all that is most noble in the often confusing, frustrating, and stressful task of teaching “hard” topics. -

Royal Bank Newsletter

The GreatDetectives An investigationof the modernmystery storyand its fascination to devotees theworld over, in whichwe attemptto unravelthe puzzleof why SherlockHolmes, InspectorMaigret and therest should live althoughthey were neverborn... [] The cookbookcalled for whiteinstead of red transcendentalplateau of literaturewhere their winein the coq-au-vin,with just a dropof sloegin fictionaldoings are, to thereader, intimate reality. 15 minutesbefore serving.The author,French We have come into their householdsjust as they foodcritic Robert Courtine, explained that this is have come into ours- in Holmes’scase a very what Madame Maigret prepares and ~simmers strangehousehold indeed. with love" for her husbandJules, better known It has beensaid, though with no suchdefinitive to detectivestory fanciersaround the world as proofas the subjecthimself would demand, that ChiefInspector Maigret of the Parispolice. Cour- SherlockHolmes is the best-knowncharacter in tinehad piecedthe recipetogether from references all of Englishliterature. He is a memberof that in severalMaigret stories. Since Madame Maigret most exclusivegroup of imaginativecreations is fromAlsace, he specifiedan AlsatianTraminger who have outlivednot only their creators,but both in the sauceand to be drunkwith the dish. their era. Throughfilms, radio, television and The use of the presenttense in the recipeis comicstrips, the peculiaritiesof Holmes’sperson- instructivein that it showshow certainliterary ality are known to vast numbers of people who creationscan loom so large in our minds as to have never read the originalHolmes stories. In becomevirtual living persons. Every reader of the what must be the ultimatetest of immortality, Maigretstories knows that Maigretis frequently many madmenevidently believe they are Sherlock detainedfrom sitting down to his wife’sdelicious Holmes. offeringsby the untimelydemands of his work. -

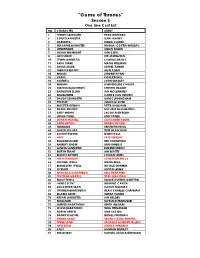

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 19 – 25 August 2017 Page 1 of 8

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 19 – 25 August 2017 Page 1 of 8 SATURDAY 19 AUGUST 2017 Read by Robert Glenister monarchy and giving a glimpse into the essential ingredients of a Written by Sarah Dunant successful sovereign. SAT 00:00 Bruce Bedford - The Gibson (b007js93) Abridged by Eileen Horne In this programme, Will uses five objects to investigate a pivotal Episode 5Saul and Elise make a grim discovery in the nursing Produced by Clive Brill aspect of the art of monarchy - the projection of magnificence. An home. Time-hopping thriller with Robert Glenister and Freddie A Pacificus production for BBC Radio 4. idea as old as monarchy itself, magnificence is the expression of Jones. SAT 02:15 Me, My Selfie and I: Aimee Fuller©s Generation power through the display of wealth and status. Will©s first object SAT 00:30 Soul Music (b04nrw25) Game (b06172qq) unites our current Queen with George III; the Gold State Coach, Series 19, A Shropshire Lad"Into my heart an air that kills Episode 5In the final part of her exploration of the selfie which has been used for coronations since 1821. Built for George From yon far country blows: phenomenon, snowboarder Aimee Fuller describes how she will III in 1762, it reflects Britain©s new found glory in its richly gilded What are those blue remembered hills, be using social media as she sets out to compete for a place at the carvings and painted panels...but the glory was to be short lived. What spires, what farms are those? next Winter Olympics. -

Ordering of Scientific Publishing

WAIT FOR IT … COMMONS, COPYRIGHT AND THE PRIVATE (RE)ORDERING OF SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING Jorge L. Contreras* Draft Mar. 4, 2012 * Visiting Associate Professor, American University Washington College of Law (permanent appointment beginning 2012-13); J.D. Harvard Law School; B.S.E.E., B.A. Rice University. The author would like to thank Jonathan Baker, Michael Carroll, Dan Cole, Mark Janis, Kimberly Kaphingst, Elinor Ostrom and David Snyder for their helpful comments, suggestions and discussion, as well as the participants in a Business Faculty Workshop at American University Washington College of Law and a Colloquium at Indiana University’s Workshop on Political Theory and Policy Analysis. An earlier draft of this paper was featured on Hearsay Culture hosted by David S. Levine, KZSU-FM - Stanford University (initial broadcast Feb. 17, 2012, available at www.hearsayculture.com). Working Draft – Please cite only with permission SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING - CONTRERAS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. THE MAKING OF A CRISIS A. The Traditional Model of Scientific Publishing B. The (New) Economics of Scientific Publishing 1. Cost 2. Revenue 3. The Journal Pricing Debate C. Leveraging Copyright 1. Why Copyright Matters 2. Author’s Assignment of Rights 3. Copyright Duration II. ADDRESSING THE CRISIS THROUGH COPYRIGHT REFORM A. Abolishing Academic Copyright? B. The Challenge of Tailoring Copyright Term 1. Effectiveness 2. Administrability 3. Political Economy III. RESPONSES IN THE SHADOW OF COPYRIGHT: THE OPEN ACCESS MOVEMENT A. Rise of the Open Access Movement B. Modes of Open Access Publication 1. Self-Archiving: The Green Route 2. Open Access Journals: The Gold Route 3. Voluntary Time-Delayed Open Access 4.