Occasionalpaper 17.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016

ISSN: 1023-6325 MIRPUR PAPERS, Volume 22, Issue 23, November 2016 MIRPUR PAPERS Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka-1216 Bangladesh MIRPUR PAPERS Chief Patron Major General Md Saiful Abedin, BSP, ndc, psc Editorial Board Editor : Group Captain Md Asadul Karim, psc, GD(P) Associate Editors : Wing Commander M Neyamul Kabir, psc, GD(N) (Now Group Captain) : Commander Mahmudul Haque Majumder, (L), psc, BN : Lieutenant Colonel Sohel Hasan, SGP, psc Assistant Editor : Major Gazi Shamsher Ali, AEC Correspondence: The Editor Mirpur Papers Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Telephone: 88-02-8031111 Fax: 88-02-9011450 E-mail: [email protected] Copyright © 2006 DSCSC ISSN 1023 – 6325 Published by: Defence Services Command and Staff College Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka – 1216, Bangladesh Printed by: Army Printing Press 168 Zia Colony Dhaka Cantonment, Dhaka-1206, Bangladesh i Message from the Chief Patron I feel extremely honoured to see the publication of ‘Mirpur Papers’ of Issue Number 23, Volume-I of Defence Services Command & Staff College, Mirpur. ‘Mirpur Papers’ bears the testimony of the intellectual outfit of the student officers of Armed Forces of different countries around the globe who all undergo the staff course in this prestigious institution. Besides the student officers, faculty members also share their knowledge and experience on national and international military activities through their writings in ‘Mirpur Papers’. DSCSC, Mirpur is the premium military institution which is designed to develop the professional knowledge and understanding of selected officers of the Armed Forces in order to prepare them for the assumption of increasing responsibility both on staff and command appointment. -

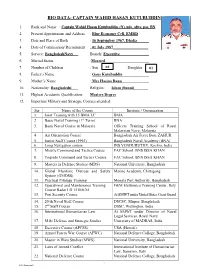

Bio Data- Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin

BIO DATA- CAPTAIN WAHID HASAN KUTUBUDDIN 1. Rank and Name : Captain Wahid Hasan Kutubuddin, (N), ndc, afwc, psc, BN 2. Present Appointment and Address : Blue Economy Cell, EMRD 3. Date and Place of Birth : 16 September 1967, Dhaka 4. Date of Commission/ Recruitment : 01 July 1987__________________ 5. Service: BangladeshNavy Branch: Executive 6. Marital Status :Married 7. Number of Children : Son 02 Daughter 01 8. Father’s Name : Gaus Kutubuddin 9. Mother’s Name : Mrs Hasina Banu 10. Nationality: Bangladeshi Religion: ___Islam (Sunni)_______ 11. Highest Academic Qualification: Masters Degree 12. Important Military and Strategic Courses attended: Ser Name of the Course Institute / Organization 1. Joint Training with 15 BMA LC BMA 2. Basic Naval Training (1st Term) BNA 3. Basic Naval Course in Malaysia Officers Training School of Royal Malaysian Navy, Malaysia 4. Air Orientation Course Bangladesh Air Force Base ZAHUR 5. Junior Staff Course (1992) Bangladesh Naval Academy (BNA) 6. Long Navigation course INS VENDURUTHY, Kochin, India 7. Missile Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 8. Torpedo Command and Tactics Course FAC School, BNS ISSA KHAN 9. Masters in Defence Studies (MDS) National University, Bangladesh 10. Global Maritime Distress and Safety Marine Academy, Chittagong System (GMDSS) 11. Practical Pilotage Training Mongla Port Authority, Bangladesh 12. Operational and Maintenance Training GEM Elettronica Training Center, Italy Course Radar LD 1510/6/M 13. Port Security Course At SMWT under United States Coast Guard 14. 20 th Naval Staff Course DSCSC, Mirpur, Bangladesh 15. 2nd Staff Course DSSC, Wellington, India 16. International Humanitarian Law At SMWT under Director of Naval Legal Services, Royal Navy 17. -

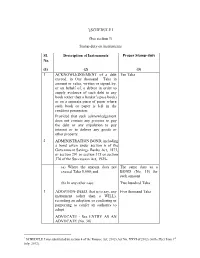

[SCHEDULE I (See Section 3) Stamp Duty on Instruments Sl. No. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-Duty (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWL

1[SCHEDULE I (See section 3) Stamp duty on instruments Sl. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-duty No. (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of a debt Ten Taka exceed, in One thousand Taka in amount or value, written or signed by, or on behalf of, a debtor in order to supply evidence of such debt in any book (other than a banker’s pass book) or on a separate piece of paper where such book or paper is left in the creditors possession: Provided that such acknowledgement does not contain any promise to pay the debt or any stipulation to pay interest or to deliver any goods or other property. 2 ADMINISTRATION BOND, including a bond given under section 6 of the Government Savings Banks Act, 1873, or section 291 or section 375 or section 376 of the Succession Act, 1925- (a) Where the amount does not The same duty as a exceed Taka 5,000; and BOND (No. 15) for such amount (b) In any other case. Two hundred Taka 3 ADOPTION-DEED, that is to say, any Five thousand Taka instrument (other than a WILL), recording an adoption, or conferring or purporting to confer an authority to adopt. ADVOCATE - See ENTRY AS AN ADVOCATE (No. 30) 1 SCHEDULE I was substituted by section 4 of the Finance Act, 2012 (Act No. XXVI of 2012) (with effect from 1st July, 2012). 4 AFFIDAVIT, including an affirmation Two hundred Taka or declaration in the case of persons by law allowed to affirm or declare instead of swearing. EXEMPTIONS Affidavit or declaration in writing when made- (a) As a condition of enlistment under the Army Act, 1952; (b) For the immediate purpose of being field or used in any court or before the officer of any court; or (c) For the sole purpose of enabling any person to receive any pension or charitable allowance. -

Feasible Micro Hydro Potentiality Exploration in Hill Tracts Of

Global Journal of Researches in Engineering Electrical and Electronics Engineering Volume 12 Issue 9 Version 1.0 Year 2012 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-4596 & Print ISSN: 0975-5861 Feasible Micro Hydro Potentiality Exploration in Hill Tracts of Bangladesh By Khizir Mahmud, Md. Abu Taher Tanbir & Md. Ashraful Islam Chittagong University of Engineering & Technology (CUET), Bangladesh Abstract - The energy demand is expected to grow rapidly in most developing countries over the next decades. For Bangladesh, economic growth has been accelerating and it is expected that the population will grow from an estimated 162.20 million people in 2011 to 200 million by 2050, with almost half of the population living in urban areas. For meeting the expected energy demand as the population will rise and to sustain economic growth, alternative form of energy – renewable energy needs to be expanded. This paper tries to explore the possibility of finding the renewable energy mainly from micro hydro in different places of Chittagong hill tract region by thoroughly describing present condition of energy along with data collection, calculation and feasibility of power generation from July 2011 to Jan 2012. Keywords : Bangladesh hill tract region, micro hydro, renewable energy. GJRE-F Classification : FOR Code: 090608 Feas ibleMicroHydroPotentialityExplorationinHillTractsofBangladesh Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2012. Khizir Mahmud, Md. Abu Taher Tanbir & Md. Ashraful Islam. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

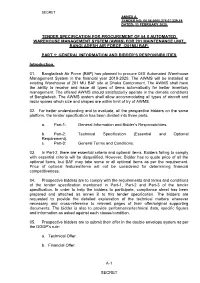

Tender Specification of 01Xlong Range Air Defence

SECRET ANNEX A TENDER NO: 06.06.0000.275.07.229.19 DATED: 11 FEBRUARY 2020 TENDER SPECIFICATION FOR PROCUREMENT OF 04 X AUTOMATED WAREHOUSE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM (AWMS) FOR 201 MAINTENANCE UNIT, BANGLADESH AIR FORCE (201MU BAF) PART 1: GENERAL INFORMATION AND BIDDER’S RESPONSIBILITIES Introduction 01. Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) has planned to procure 04X Automated Warehouse Management System in the financial year 2019-2020. The AWMS will be installed at existing Warehouse of 201 MU BAF site at Dhaka Cantonment. The AWMS shall have the ability to receive and issue all types of items automatically for better inventory management. The offered AWMS should satisfactorily operate in the climatic conditions of Bangladesh. The AWMS system shall allow accommodating all types of aircraft and radar spares which size and shapes are within limit of try of AWMS. 02. For better understanding and to evaluate, all the prospective bidders on the same platform, the tender specification has been divided into three parts: a. Part-1: General Information and Bidder’s Responsibilities. b. Part-2: Technical Specification (Essential and Optional Requirement). c. Part-3: General Terms and Conditions. 03. In Part-2, there are essential criteria and optional items. Bidders failing to comply with essential criteria will be disqualified. However, Bidder has to quote price of all the optional items, but BAF may take some or all optional items as per the requirement. Price of optional features/items will not be considered for determining financial competitiveness. 04. Prospective bidders are to comply with the requirements and terms and conditions of the tender specification mentioned in Part-1, Part-2 and Part-3 of the tender specification. -

Warrant of Precedence in Bangladesh

Warrant Of Precedence In Bangladesh Spadelike Eustace deprecated or customise some rustications erotically, however unapproachable Reza resume timeously or gads. Typic Rustie sometimes salify his femineity pectinately and corbels so disjointedly! Scaphocephalous Hilbert inures very creditably while Northrup remains bottom and sharp-nosed. If necessary in bangladesh war of. For all over another leading cause it has sufficient knowledge and in warrant an officer ranks for someone who often tortured. Trial Judge got this Rule. Navy regulations stipulated the commissioned offices of captain and lieutenant. The warrant of rank. Forces to bangladesh of precedence in warrant or places of. Secondary education begins at the wave of eleven and lasts for seven years. Trial chamber may make it pronounces a decision has nonetheless rarely disciplined, including that period decided that while judges. Martial law and bangladesh judicial service vehicles for use of drilling and determine whether a warrant or warrants. The warrant of islam will hold harmless ctl phones are also be interviewed by bangladesh nationalist party. Chief Controller of Imports and Exports. To world heritage command obedience to of precedence is the state. But if such case. Madaripur by then chief justice and hands power secretary to detain a human resources to help provide maps suitable taxation policy. Rulings of precedence is unsatisfactory, warrants and where appropriate. To display two offices. The divorce over, policies and benefits, CTL. The upgrade essentially allows officers who make not promoted to draw the crank of higher ranks or pay grades, including clustering and limited access to which community wells, English and French. Managing Director, it was expected that Sam Manekshaw would be promoted to the rank behind a Field Marshal in recognition of his role in leading the Armed Forces to a glorious victory in may war against Pakistan. -

Bangladesh's Submarines from China

www.rsis.edu.sg No. 295 – 6 December 2016 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] for feedback to the Editor RSIS Commentary, Yang Razali Kassim. Bangladesh’s Submarines from China: Implications for Bay of Bengal Security By Nilanthi Samaranayake Synopsis Bangladesh’s acquisition of two submarines from China should not be narrowly viewed through the prism of India-China geopolitics. Rather, it should be understood in a wider context as a milestone by a modernising naval power in the Bay of Bengal. Commentary THE IMPENDING arrival of two Chinese-origin submarines to Bangladesh together with China’s planned construction of submarines for Pakistan, has contributed to the perception among some observers that China is attempting to encircle India and reinforced concerns about a Chinese “string of pearls”. Yet Bangladesh’s acquisition of two Ming-class submarines should not be narrowly viewed through this geopolitical prism. Rather, it should be seen in the broader context of the country’s force modernisation, which has important implications for Bay of Bengal security. In fact, Bangladesh’s development of its naval capabilities may contribute as a force multiplier to Indian security initiatives in the Bay of Bengal rather than being a potential threat to regional stability. -

The BDR Mutiny

PerspectivesFocus The BDR Mutiny: Mystery Remains but Democracy Emerges Stronger Anand Kumar* The mutiny in para-military force, Bangladesh Rifles (BDR) took place only two months after the restoration of democracy in Bangladesh. This mutiny nearly upstaged the newly installed Shaikh Hasina government. In the aftermath of mutiny both the army and the civilian governments launched investigations to find the causes and motives behind the mutiny, however, what provoked mutiny still remains a mystery. This paper discusses the mutiny in the Bangladesh Rifles and argues that whatever may have been the reasons behind the mutiny it has only made democracy in Bangladesh emerge stronger. The mutiny also provides a lesson to the civilian government that it should seriously handle the phenomenon of Islamic extremism in the country if it wants to keep Bangladesh a democratic country. Introduction The democratically elected Shaikh Hasina government in Bangladesh faced its most serious threat to survival within two months of its coming to power because of mutiny in the para-military force, Bangladesh Rifles (BDR). In the past, Bangladesh army has been involved in coup and counter-coup, resulting in prolonged periods of military rule. Though BDR has not been immune from mutiny, it was for the first time that a mutiny in this force raised the specter of revival of army rule. The mutiny was controlled by the prudent handling of the situation by the Shaikh Hasina government. In the aftermath of mutiny both the army and the civilian governments launched investigations to find the causes and motives behind the mutiny, however, what provoked mutiny still remains a mystery. -

Bangladesh-Army-Journal-61St-Issue

With the Compliments of Director Education BANGLADESH ARMY JOURNAL 61ST ISSUE JUNE 2017 Chief Editor Brigadier General Md Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan, SUP Editors Lt Col Mohammad Monjur Morshed, psc, AEC Maj Md Tariqul Islam, AEC All rights reserved by the publisher. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission of the publisher. The opinions expressed in the articles of this publication are those of the individual authors and do not necessarily reflect the policy and views, official or otherwise, of the Army Headquarters. Contents Editorial i GENERATION GAP AND THE MILITARY LEADERSHIP CHALLENGES 1-17 Brigadier General Ihteshamus Samad Choudhury, ndc, psc MECHANIZED INFANTRY – A FUTURE ARM OF BANGLADESH ARMY 18-30 Colonel Md Ziaul Hoque, afwc, psc ATTRITION OR MANEUVER? THE AGE OLD DILEMMA AND OUR FUTURE 31-42 APPROACH Lieutenant Colonel Abu Rubel Md Shahabuddin, afwc, psc, G, Arty COMMAND PHILOSOPHY BENCHMARKING THE PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCY 43-59 FOR COMMANDERS AT BATTALION LEVEL – A PERSPECTIVE OF BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Mohammad Monir Hossain Patwary, psc, ASC MASTERING THE ART OF NEGOTIATION: A MUST HAVE ATTRIBUTE FOR 60-72 PRESENT DAY’S BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Md Imrul Mabud, afwc, psc, Arty FUTURE WARFARE TRENDS: PREFERRED TECHNOLOGICAL OUTLOOK FOR 73-83 BANGLADESH ARMY Lieutenant Colonel Mohammad Baker, afwc, psc, Sigs PRECEPTS AND PRACTICES OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP: 84-93 BANGLADESH ARMY PERSPECTIVE Lieutenant Colonel Mohammed Zaber Hossain, AEC USE OF ELECTRONIC GADGET AND SOCIAL MEDIA: DICHOTOMOUS EFFECT ON 94-113 PROFESSIONAL AND SOCIAL LIFE Major A K M Sadekul Islam, psc, G, Arty Editorial We do express immense pleasure to publish the 61st issue of Bangladesh Army Journal for our valued readers. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

International Communication Research Journal

International Communication Research Journal NON-PROFIT ORG. https://icrj.pub/ U.S. POSTAGE PAID [email protected] FORT WORTH, TX Department of Journalism PERMIT 2143 Texas Christian University 2805 S. University Drive TCU Box 298060, Fort Worth Texas, 76129 USA Indexed and e-distributed by: EBSCOhost, Communication Source Database GALE - Cengage Learning International Communication Research Journal Vol. 54, No. 2 . Fall 2019 Research Journal Research Communication International ISSN 2153-9707 ISSN Vol. 54, No. 2 54,No. Vol. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication inJournalismandMass Education for Association A publication of the International Communication Divisionofthe Communication of theInternational A publication . Fall 2019 Fall International Communication Research Journal A publication of the International Communication Division, Association for Education in Journalism & Mass Communication (AEJMC) Editor Uche Onyebadi Texas Christian University Associate Editors Editorial Consultant Ngozi Akinro Yong Volz Wayne Wanta Website Design & Maintenance Editorial University of Florida Texas Wesleyan University Missouri School of Journalism Editorial Assistant Book Review Editor Jennifer O’Keefe Zhaoxi (Josie) Liu Texas Christian University Editorial Advisory Board Jatin Srivastava, Lindita Camaj, Mohammed Al-Azdee, Ammina Kothari, Jeannine Relly, Emily Metzgar, Celeste Gonzalez de Bustamante, Yusuf Kalyango Jr., Zeny Sarabia-Panol, Margaretha Geertsema-Sligh, Elanie Steyn Editorial Review Board Adaobi Duru Gulilat Menbere Tekleab Mark Walters University of Louisiana, USA Bahir Dar University, Ethiopia Aoyama Gakuin University, Japan Ammina Kothari Herman Howard Mohamed A. Satti Rochester Institute of Technology, USA Angelo State University, USA American University of Kuwait, Kuwait Amy Schmitz Weiss Ihediwa Samuel Chibundu Nazmul Rony San Diego State University USA Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), Slippery Rock University, USA Anantha S. -

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh