Plant and Wildlife Naming System in Southern Pumi1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TONES of NUMERALS and NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: on STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA and LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS

Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area Volume 34.1 — April 2011 THE TONES OF NUMERALS AND NUMERAL-PLUS-CLASSIFIER PHRASES: ON STRUCTURAL SIMILARITIES BETWEEN NAXI, NA AND LAZE* Alexis Michaud LACITO-CNRS Abstract: Numeral-plus-classifier phrases have relatively complex tone patterns in Naxi, Na (a.k.a. Mosuo) and Laze (a.k.a. Shuitian). These tone patterns have structural similarities across the three languages. Among the numerals from ‘1’ to ‘10’, three pairs emerge: ‘1’ and ‘2’ always have the same tonal behaviour; likewise, ‘4’ and ‘5’ share the same tone patterns, as do ‘6’ and ‘8’. Even those tone patterns that are irregular in view of the synchronic phonology of the languages at issue are no exception to the structural identity within these three pairs of numerals. These pairs also behave identically in numerals from ‘11’ to ‘99’ and above, e.g. ‘16’ and ‘18’ share the same tone pattern. In view of the paucity of irregular morphology—and indeed of morphological alternations in general—in these languages, these structural properties appear interesting for phylogenetic research. The identical behaviour of these pairs of numerals originates in morpho- phonological properties that they shared at least as early as the stage preceding the separation of Naxi, Na and Laze, referred to as the Proto-Naish stage. Although no reconstruction can be proposed as yet for these shared properties, it is argued that they provide a hint concerning the phylogenetic closeness of the three languages. Keywords: tone; numerals; classifiers; morpho-tonology; Naxi; Na; Mosuo; Laze; Muli Shuitian; Naish languages; phylogeny. 1. -

An Internal Reconstruction of Tibetan Stem Alternations1

Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 110:2 (2012) 212–224 AN INTERNAL RECONSTRUCTION OF TIBETAN STEM ALTERNATIONS1 By GUILLAUME JACQUES CNRS (CRLAO), EHESS ABSTRACT Tibetan verbal morphology differs considerably from that of other Sino-Tibetan languages. Most of the vocalic and consonantal alternations observed in the verbal paradigms remain unexplained after more than a hundred years of investigation: the study of historical Tibetan morphology would seem to have reached an aporia. This paper proposes a new model, explaining the origin of the alternations in the Tibetan verb as the remnant of a former system of directional prefixes, typologically similar to the ones still attested in the Rgyalrongic languages. 1. INTRODUCTION Tibetan verbal morphology is known for its extremely irregular conjugations. Li (1933) and Coblin (1976) have successfully explained some of the vocalic and consonantal alternations in the verbal system as the result of a series of sound changes. Little substantial progress has been made since Coblin’s article, except for Hahn (1999) and Hill (2005) who have discovered two additional conjugation patterns, the l- and r- stems respectively. Unlike many Sino-Tibetan languages (see for instance DeLancey 2010), Tibetan does not have verbal agreement, and its morphology seems mostly unrelated to that of other languages. Only three morphological features of the Tibetan verbal system have been compared with other languages. First, Shafer (1951: 1022) has proposed that the a ⁄ o alternation in the imperative was related to the –o suffix in Tamangic languages. This hypothesis is well accepted, though Zeisler (2002) has shown that the so-called imperative (skul-tshig) was not an imperative at all but a potential in Old Tibetan. -

No.9 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter June 1990

[Last updated: 28 April 1992] ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- No.9 Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter June 1990 This NEWSLETTER is edited by Gehan Wijeyewardene and published in the Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies; printed at Central Printery; the masthead is by Susan Wigham of Graphic Design (all of The Australian National University ).The logo is from a water colour , 'Tai women fishing' by Kang Huo Material in this NEWSLETTER may be freely reproduced with due acknowledgement. Correspondence is welcome and contributions will be given sympathetic consideration. (All correspondence to The Editor, Department of Anthropology, RSPacS, ANU, Box 4 GPO, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia.) Number Nine June 1990 ISSN 1032-500X The International Conference on Thai Studies, Kunming 1990 There was some question, in the post Tien An Men period, as to whether the conference would proceed. In January over forty members of Thammasart University faculty issued an open letter to the organizers, which in part read, A meeting in China at present would mean a tacit acceptance of the measures taken by the state, unless there will be an open critical review. Many north American colleagues privately expressed similar views. This Newsletter has made its views on Tien An Men quite clear, and we can sympathize with the position taken by our colleagues. Nevertheless, there seems to be some selectivity of outrage, when no word of protest was heard from some quarters about the continuing support given by the Chinese government to the murderous Khmer Rouge. This does not apply to the Thai academic community, sections of which were in the vanguard of the movement to reconsider Thai government policy on this issue. -

"Brightening" and the Place of Xixia (Tangut)

1 "Briiighttteniiing" and ttthe plllace of Xiiixiiia (Tanguttt) iiin ttthe Qiiiangiiic branch of Tiiibettto-Burman* James A. Matisoff University of California, Berkeley 1.0 Introduction Xixia (Tangut) is an extinct Tibeto-Burman language, once spoken in the Qinghai/Gansu/Tibetan border region in far western China. Its complex logographic script, invented around A.D. 1036, was the vehicle for a considerable body of literature until it gradually fell out of use after the Mongol conquest in 1223 and the destruction of the Xixia kingdom.1 A very large percentage of the 6000+ characters have been semantically deciphered and phonologically reconstructed, thanks to a Xixia/Chinese glossary, Tibetan transcriptions, and monolingual Xixia dictionaries and rhyme-books. The f«anqi\e method of indicating the pronunciation of Xixia characters was used both via other Xixia characters (in the monolingual dictionaries) and via Chinese characters (in the bilingual glossary Pearl in the Palm, where Chinese characters are also glossed by one or more Xixia ones). Various reconstruction systems have been proposed by scholars, including M.V. Sofronov/K.B. Keping, T. Nishida, Li Fanwen, and Gong Hwang-cherng. This paper relies entirely on the reconstructions of Gong.2 After some initial speculations that Xixia might have belonged to the Loloish group of Tibeto-Burman languages, scholarly opinion has now coalesced behind the geographically plausible opinion that it was a member of the "Qiangic" subgroup of TB. The dozen or so Qiangic languages, spoken in Sichuan Province and adjacent parts of Yunnan, were once among the most obscure in the TB family, loosely lumped together as the languages of the Western Barbarians (Xifan = Hsifan). -

1 Compulsory Mobility, Hierarchical Imaginary, and Education in China's

London Review of Education Volume 12, Number 1, March 2014 Empire at the margins:1 Compulsory mobility, hierarchical imaginary, and education in China’s ethnic borderland Peidong Yang* Department of Education, University of Oxford, UK This paper presents an ethnographic interpretation of education as a social technology of state sovereign power and governing in the borderlands of contemporary China. Illustrated with snapshots from ethnographic fieldwork conducted in a Pumi (Premi) ethnic village located along China’s south-western territorial margins, it is argued that the hierarchical structure of the education system, coupled with the arduous and yet compulsory mobility entailed in educational participation, powerfully shapes the social and political imaginaries of peripheral citizens. Education serves simultaneously as a distance-demolishing technology and a hierarchy- establishing technology that counters the ‘frictions of terrain’ that traditionally presented a problem to the state for governing such geographically inaccessible borderlands. Keywords: China; education; minority; state; power; imaginary Introduction Historian and philosopher Michel Foucault in his seminal work Discipline and Punish (1977: 181–4) offers some brilliant analyses of schooling/education. He sheds light on the French military school regime and what he calls the ‘techniques of power’ employed in the school to discipline pupils, including processes such as normalization, individualization, and ranking. Through examining such processes, he shows that it is not ideas or ideologies taught in the school that accomplish the state’s aims of subject formation and discipline; instead, he argues, it is concrete techniques, mechanisms, and instruments that achieve this. In this ethnographically based paper, I adopt Foucault’s analytical perspective of focusing on the (social) technologies of power and discipline, and apply it to the domain of education in China’s ethnic minority borderlands. -

Pumi, a Language of China of the Qiangic Language Family

Christie Voelker 1. Description 1.1 Name(s) of society, language, and language family: Pumi, a language of China of the Qiangic language family. Divided into Northern and Southern (1) Often referred to as Premi. “Later, after having read all I could find published in Chinese on the Pumi minzu, or Premi people, as many of them call themselves…”(2, p.xiv) Call themselves Prmi, also referred to as Xifan by the Chinese. “Some of them explained to me that in their own language they referred to themselves as Prmi, and that Xifan was the accepted ‘address by others’. ‘All other peoples call us Xifan. So we refer to ourselves as Xifan when we talk to the other peoples in Chinese. Now our official name is Pumi. But in daily conversations people are still used to Xifan’”(3, 43). 1.2 ISO code (3 letter code from ethnologue.com): pmi (Northern), pmj (Southern) (1) 1.3 Location (latitude/longitude): Southwest Sichuan Province and Northwest Yunnan Province (1) Approximately 26N, 102E 1.4 Brief history: The Pumi are thought to have migrated from Qinghai to Sichuan and Yunnan Provinces around the thirteenth century. o “The language spoken by today’s Prmi people is one of perhaps twelve or so languages belonging to the Qiangic subfamily of Tibeto-Burman and the other languages of this small subfamily are distributed along what is probably a historical migration corridor from the Qinghai or northeastern Tibet area… This seems to indicate that speakers of this group of languages migrated southward along this route, culminating in the Prmi, who are the southernmost Qiangic speakers”(4, 63). -

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393

Sino-Tibetan Languages 393 Gair J W (1998). Studies in South Asian linguistics: Sinhala Government Press. [Reprinted Sri Lanka Sahitya and other South Asian languages. Oxford: Oxford Uni- Mandalaya, Colombo: 1962.] versity Press. Karunatillake W S (1992). An introduction to spoken Sin- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1974). Literary Sinhala. hala. Colombo: Gunasena. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Program. Karunatillake W S (2001). Historical phonology of Sinha- Gair J W & Karunatillake W S (1976). Literary Sinhala lese: from old Indo-Aryan to the 14th century AD. inflected forms: a synopsis with a transliteration guide to Colombo: S. Godage and Brothers. Sinhala script. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University South Asia Macdougall B G (1979). Sinhala: basic course. Program. Washington D.C.: Foreign Service Institute, Department Gair J W & Paolillo J C (1997). Sinhala (Languages of the of State. world/materials 34). Mu¨ nchen: Lincom. Matzel K & Jayawardena-Moser P (2001). Singhalesisch: Gair J W, Karunatillake W S & Paolillo J C (1987). Read- Eine Einfu¨ hrung. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ings in colloquial Sinhala. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1970). An anthology of Sinhalese South Asia Program. literature up to 1815. London: George Allen and Unwin Geiger W (1938). A grammar of the Sinhalese language. (English translations). Colombo: Royal Asiatic Society. Reynolds C H B (ed.) (1987). An anthology of Sinhalese Godakumbura C E (1955). Sinhalese literature. Colombo: literature of the twentieth century. Woodchurch, Kent: Colombo Apothecaries Ltd. Paul Norbury/Unesco (English translations). Gunasekara A M (1891). A grammar of the Sinhalese Reynolds C H B (1995). Sinhalese: an introductory course language. -

Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau

IPP740 REV World Bank-financed Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Ethnic Minority Development Plan of the Yunnan Highway Assets Management Project Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Yunnan Provincial Highway Bureau July 2014 Public Disclosure Authorized EMDP of the Yunnan Highway Assets management Project Summary of the EMDP A. Introduction 1. According to the Feasibility Study Report and RF, the Project involves neither land acquisition nor house demolition, and involves temporary land occupation only. This report aims to strengthen the development of ethnic minorities in the project area, and includes mitigation and benefit enhancing measures, and funding sources. The project area involves a number of ethnic minorities, including Yi, Hani and Lisu. B. Socioeconomic profile of ethnic minorities 2. Poverty and income: The Project involves 16 cities/prefectures in Yunnan Province. In 2013, there were 6.61 million poor population in Yunnan Province, which accounting for 17.54% of total population. In 2013, the per capita net income of rural residents in Yunnan Province was 6,141 yuan. 3. Gender Heads of households are usually men, reflecting the superior status of men. Both men and women do farm work, where men usually do more physically demanding farm work, such as fertilization, cultivation, pesticide application, watering, harvesting and transport, while women usually do housework or less physically demanding farm work, such as washing clothes, cooking, taking care of old people and children, feeding livestock, and field management. In Lijiang and Dali, Bai and Naxi women also do physically demanding labor, which is related to ethnic customs. Means of production are usually purchased by men, while daily necessities usually by women. -

Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems

Sino-Tibetan numeral systems: prefixes, protoforms and problems Matisoff, J.A. Sino-Tibetan Numeral Systems: Prefixes, Protoforms and Problems. B-114, xii + 147 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1997. DOI:10.15144/PL-B114.cover ©1997 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wunn EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), Thomas E. Dutton, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at the Australian National University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. Publications in Series A, B and C and textbooks in Series D are refereed by scholars with re levant expertise who are normally not members of the editorial board. -

Pumi, Northernnorthern

Pumi,Pumi, NorthernNorthern A widespread, isolated section of south- per cent lexical similarity with Southern west Sichuan Province in China is home Pumi, which is spoken in Yunnan Province. to approximately 40,000 Northern Pumi The Southern Pumi have not been included people. Most are located in and around in this book because they are primarily Sichuan Muli County, described as ‘a rich posses- animists and polytheists. Few are adherents sion. The rivers, especially the Litang, of Buddhism. carry gold and produce a considerable Yunnan A Northern Pumi king presided over the Pumi Northern 1 revenue.’ Northern Pumi is also spoken former Buddhist monastery town of Muli Population: in Zuosuo and Yousuo districts of Yanyuan until the 1950s. The king once ‘held sway 39,000 (2000) County and in the Sanyanlong and Dabao over a territory of 9,000 square miles—an 48,100 (2010) 2 59,200 (2020) districts of Jiulong County. Seven thousand area slightly larger than Massachusetts’.5 Northern Pumi live in the Yongning District Countries: China The rulers of Muli ‘are said to be of Buddhism: Tibetan of Ninglang County in northern Yunnan Manchu origin. Christians: none known Province. They were given In the past, the the sovereignty Northern Pumi of the kingdom were com- in perpetuity in monly known recognition of as Xifan, a valorous services Overview of the derogatory rendered to Northern Pumi Chinese name Yungcheng, the Other Names: Xifan, Hsifan, meaning famous Manchu Northern Pumi, Chrame, ‘barbarians of emperor, who Ch’rame, Tshomi, Sichuan Pumi the west’—a ascended the Population Sources: name applied throne in 1723.’6 30,000 in China (1987, not only to The king ruled Language Atlas of China) this group but with ‘absolute Language: Sino-Tibetan, Tibeto-Burman, Tangut-Qiang, sometimes spiritual and Qiangic also used for temporal sway’7 Dialects: 4 (Tuoqi, Sanyanlong, all Tibetans. -

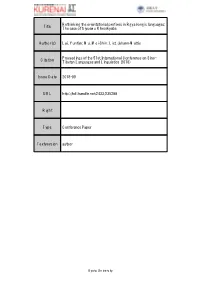

Title Rethinking the Orientational Prefixes in Rgyalrongic Languages

Rethinking the orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages: Title The case of Siyuewu Khroskyabs Author(s) Lai, Yunfan; Wu, Mei-Shin; List, Johann-Mattis Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235288 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Computer-Assisted Language Comparison CALC http://calc.digling.org Rethinking the orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages: The case of Siyuewu Khroskyabs Yunfan Lai* with contributions by Mei-Shin Wu* and Johann-Mattis List* July 2018 1 Background Information 1.1 Rgyalrongic languages • Rgyalrongic is a group of Burmo-Qiangic languages in the Sino-Tibetan family mainly spoken in Western Sichuan, including Rgyalrong languages (Situ, Tshob- dun, Japhug and Zbu), Horpa languages and Khroskyabs dialects (Sun, 2000b,a). • Figure 1 shows the location of the languages under analysis. • These languages are highly complex both phonologically and morphologically. • Verbal morphology in Rgyalrongic, in particular, exhibits extraordinary affixation and various morphological processes. Computer-Assisted* Language Comparison (CALC), Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolu- tion, Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History 1 Figure 1: Location of Rgyalrongic languages N 27.5 30.0 32.5 0 100 200 km 100 105 110 1.2 Orientational prefixes in Rgyalrongic languages • Burmo-Qiangic languages: “orientational prefixes” or “directional prefixes” (LaPolla, 2017). • Two major functions – Indicating the directions to which the action denoted by the verb (if applicable) – Lexically assigned to verb stems to indicate TAME properties. 1.3 Goal of the paper This paper will focus the first function of orientational prefixes in one of the Rgyalrongic languages, namely Siyuewu Khroskyabs, by re-examining the traditional approaches and providing an alternative way to analyse them. -

Editorial Note

Editorial Note This volume was produced under difficult conditions. The publication of articles was not only very slow; the number of articles was also reduced due to circumstances beyond our control - the heavy flood in Thailand during October to December 2011. So we ask the reader’s indulgence for any effects this may have on the volume. For this volume, we are pleased to present articles focused on the following languages: Jieyang-Hakka, Jowai-Pnar, Lai, Pumi, Ten-edn, Tai and Viet-Mường; these papers make contributions to language documentation, especially in phonetics and lexicography, and better understanding the historical processes of language diversification. Additionally there are typological papers on phonetics and narrative in Mon-Khmer languages which address important general issues. Graceful acknowledgement should be made to Paul Sidwell for seeing the final volume through to press, and to Brian Migliazza for facilitating the publication of his volume. The Mon-Khmer Studies (MKS) was first published by the Linguistic Circle of Saigon and the Summer Institute of Linguistics in 1964. After nearly 50 years, the print edition will be discontinued. From the volume 41 onward, the MKS is going completely digital and open access. The journal will move to a continuous online publication model, consistent with trends in academic publishing internationally. Also, arrangements will be made for print-on- demand delivery, although we expect electronic distribution to become normal. We thank our readers, authors, reviewers and editors for their continuing support of the journal, now and into the future. Naraset Pisitpanporn for MKS Editorial Board April 2012 iv Table of Contents Editorial Note.……………………………………………………………...….iv Articles John D.