THE ROMANS in the Tees Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Northgate Reconstruction

131 7 THE NORTHGATE RECONSTRUCTION P Holder and J Walker INTRODUCTION have come from the supposedly ancient quarries at Collyhurst some few kilometres north-east of the The Unit was asked to provide advice and fort. As this source was not available, Hollington assistance to Manchester City Council so that the Red Sandstone from Staffordshire was used to form City could reconstruct the Roman fort wall and a wall of coursed facing blocks 200-320 mm long by defences at Manchester as they would have appeared 140-250 mm deep by 100-120 mm thick. York stone around the beginning of the 3rd century (Phase 4). was used for paving, steps and copings. A recipe for the right type of mortar, which consisted of This short report has been included in the volume three parts river sand, three parts building sand, in order that a record of the archaeological work two parts lime and one part white cement, was should be available for visitors to the site. obtained from Hampshire County Council. The Ditches and Roods The Wall and Rampart The Phase 4a (see Chapter 4, Area B) ditches were Only the foundations and part of the first course re-establised along their original line to form a of the wall survived (see Chapter 4, Phase 4, Area defensive circuit consisting of an outer V-shaped A). The underlying foundations consisted of ditch in front of a smaller inner ditch running interleaved layers of rammed clay and river close to the fort wall. cobble. On top of the foundations of the fort wall lay traces of a chamfered plinth (see Chapter 5g) There were three original roads; the main road made up of large red sandstone blocks, behind from the Northgate that ran up to Deansgate, the which was a rough rubble backing. -

New Methodologies for the Documentation of Fortified Architecture in the State of Ruins

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-5/W1, 2017 GEOMATICS & RESTORATION – Conservation of Cultural Heritage in the Digital Era, 22–24 May 2017, Florence, Italy NEW METHODOLOGIES FOR THE DOCUMENTATION OF FORTIFIED ARCHITECTURE IN THE STATE OF RUINS F. Fallavollita a, A. Ugolini a a Dept. of Architecture, University of Bologna, Viale del Risorgimento, 2, 40136 Bologna, Italy - (federico.fallavollita, andrea.ugolini)@unibo.it KEY WORDS: Castles, Laser Scanner, Digital Photogrammetry, Architectural Survey, Restoration ABSTRACT: Fortresses and castles are important symbols of social and cultural identity providing tangible evidence of cultural unity in Europe. They are items for which it is always difficult to outline a credible prospect of reuse, their old raison d'être- namely the military, political and economic purposes for which they were built- having been lost. In recent years a Research Unit of the University of Bologna composed of architects from different disciplines has conducted a series of studies on fortified heritage in the Emilia Romagna region (and not only) often characterized by buildings in ruins. The purpose of this study is mainly to document a legacy, which has already been studied in depth by historians, and previously lacked reliable architectural surveys for the definition of a credible as well as sustainable conservation project. Our contribution will focus on different techniques and methods used for the survey of these architectures, the characteristics of which- in the past- have made an effective survey of these buildings difficult, if not impossible. The survey of a ruin requires, much more than the evaluation of an intact building, reading skills and an interpretation of architectural spaces to better manage the stages of documentation and data processing. -

Darlington Gateway Strategy a Report for Darlington Borough Council

Darlington Gateway Strategy A Report for Darlington Borough Council Building Design Partnership with King Sturge, Regeneris and CIP December 2006 Darlington Gateway Strategy – Strand D CONTENTS Executive Summary 1. Introduction 2. Darlington Gateway – the context for further progress 3. Darlington Gateway – the context for strategy development 4. Darlington Gateway – a strategy to 2020 5. Darlington Gateway - a framework for Sustainable Economic Growth 6. Darlington Gateway - Making it Happen – the Action Plan Appendices Appendix 1 - Town Centre Expansion – Outline Development and Feasibility Assessment Appendix 2 - Employment Land Portfolio (plans) Building Design Partnership with King Sturge, Regeneris and CIP December 2006 Darlington Gateway Strategy – Strand D Executive Summary Introduction 1. This Gateway Strategy updates and develops on the original Darlington Gateway Development Framework, produced in 2003. This strategy is intended to establish economic regeneration priorities and key actions in Darlington for the period 2006 – 2020. Darlington Gateway 2003 2. The Darlington Gateway 2003 highlighted the strong locational and quality of life advantages of Darlington. The strategy identified business/financial services, logistics/distribution and retail as key sectors for Darlington. Darlington’s portfolio of sites and property and future development was to be geared towards these sectors. Darlington Gateway – Assessment to Date 3. The Darlington Gateway has facilitated a strong rate of development activity in the Borough in recent years. 4. At this early stage in the implementation of the Gateway strategy, key indicators present a very positive picture: x Between 2006 and 2010 it is estimated that close to 1.1 million sq ft of floorspace (office and industrial) is set to become available in Darlington under the Gateway banner with the potential to yield around 4300 jobs (c. -

Galway City Walls Conservation, Management and Interpretation Plan

GALWAY CITY WALLS CONSERVATION, MANAGEMENT & INTERPRETATION PLAN MARCH 2013 Frontispiece- Woman at Doorway (Hall & Hall) Howley Hayes Architects & CRDS Ltd. were commissioned by Galway City Coun- cil and the Heritage Council to prepare a Conservation, Management & Interpre- tation Plan for the historic town defences. The surveys on which this plan are based were undertaken in Autumn 2012. We would like to thank all those who provided their time and guidance in the preparation of the plan with specialist advice from; Dr. Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Dr. Kieran O’Conor, Dr. Jacinta Prunty & Mr. Paul Walsh. Cover Illustration- Phillips Map of Galway 1685. CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 UNDERSTANDING THE PLACE 6 3.0 PHYSICAL EVIDENCE 17 4.0 ASSESSMENT & STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 28 5.0 DEFINING ISSUES & VULNERABILITY 31 6.0 CONSERVATION PRINCIPLES 35 7.0 INTERPRETATION & MANAGEMENT PRINCIPLES 37 8.0 CONSERVATION STRATEGIES 41 APPENDICES Statutory Protection 55 Bibliography 59 Cartographic Sources 60 Fortification Timeline 61 Endnotes 65 1.0 INTRODUCTION to the east, which today retains only a small population despite the ambitions of the Anglo- Norman founders. In 1484 the city was given its charter, and was largely rebuilt at that time to leave a unique legacy of stone buildings The Place and carvings from the late-medieval period. Galway City is situated on the north-eastern The medieval street pattern has largely been shore of a sheltered bay on the west coast of preserved, although the removal of the walls Ireland. It is located at the mouth of the River during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Corrib, which separates the east and western together with extra-mural developments as the sides of the county. -

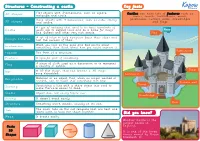

KO DT Y3 Castles

Structures - Constructing a castle Key facts Flat objects with 2-dimensions, such as square, 2D shapes Castles can have lots of features such as rectangle and circle. towers, turrets, battlements, moats, Solid objects with 3-dimensions, such as cube, oblong gatehouses, curtain walls, drawbridges 3D shapes and sphere. and flags. A type of building that used to be built hundreds of Castle years ago to defend land and be a home for Kings and Queens and other very rich people. Flag A set of rules to help designers focus their ideas and Design criteria test the success of them. When you look at the good and bad points about Evaluation something, then think about how you could improve it. Battlement Façade The front of a structure. Feature A specific part of something. Flag A piece of cloth used as a decoration or to represent a country or symbol. Tower Net A 2D flat shape, that can become a 3D shape once assembled. Gatehouse Recyclable Material or an object that, when no longer wanted or needed, can be made into something else new. Curtain wall Turret Scoring Scratching a line with a sharp object into card to make the card easier to bend. Stable Object does not easily topple over. Drawbridge Strong It doesn't break easily. Moat Structure Something which stands, usually on its own. Tab The small tabs on the net template that are bent and glued down to hold the shape together. Did you know? Weak It breaks easily. Windsor Castle is the largest castle in Basic England. -

The Inner City Seljuk Fortifications of Rey: Case Study of Rashkān

Archive of SID THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES Volume 27, Issue 3 (2020), Pages 1-99 Director-in-Charge: Seyed Mehdi Mousavi, Associate Professor of Archaeology Editor-in-Chief: Arsalan Golfam, Associate Professor of Linguistics Managing Editors: Shahin Aryamanesh, PhD of Archaeology, Tissaphernes Archaeological Research Group English Edit by: Ahmad Shakil, PhD Published by Tarbiat Modares University Editorial board: Ehsani, Mohammad; Professor of Sport Management, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Ghaffari, Masoud; Associate Professor of Political Science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Hafezniya, Mohammadreza; Professor in Political Geography and Geopolitics, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Khodadad Hosseini, Seyed Hamid; Professor in Business, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Kiyani, Gholamreza; Associate Professor of Language & Linguistics, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Manouchehri, Abbas; Professor of Political science, Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran Ahmadi, Hamid; Professor of Political science, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran Karimi Doostan, Gholam Hosein; Professor of Linguistics, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran Mousavi Haji, Seyed Rasoul; Professor of Archaeology, Mazandaran University, Mazandaran, Iran Yousefifar, Shahram; Professor of History, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran Karimi Motahar, Janallah; Professor of Russian Language, Tehran University, Tehran, Iran Mohammadifar, Yaghoub; Professor of Archaeology, Bu-Ali Sina University, Hamedan, Iran The International Journal of Humanities is one of the TMU Press journals that is published by the responsibility of its Editor-in-Chief and Editorial Board in the determined scopes. The International Journal of Humanities is mainly devoted to the publication of original research, which brings fresh light to bear on the concepts, processes, and consequences of humanities in general. It is multi-disciplinary in the sense that it encourages contributions from all relevant fields and specialized branches of the humanities. -

Downloaded from the Website

2008 Issue Number 1 SHTAV NEWS Journal of The Association of small Historic Towns and Villages of the UK above RICHMOND YORKSHIRE Understanding Market Towns The Village 1 some family lines to be followed down the centuries. The writing of this book grew out of a relatively simple request by the Atherstone Civic Society, in 2002/3, for funds to preserve an ancient animal pound. The Countryside Agency, and subsequently the Heritage Lottery Fund, insisted that a wider project be embarked upon, one that would involve the entire community. The HART project was born. Additional funding came from Nationwide (through the Countryside Agency), Advantage West Midlands and Atherstone & Polesworth Market Towns Programme. From the £35,000 in grants, funds were used to pay for the first professional historic building survey of Atherstone town centre. The services of a trained archivist were also employed. The town has benefited unexpectedly from the information these specialists were able to provide, for example by now having a survey of all the town's buildings of historic architectural significance. The size of the task undertaken by the HART group is reflected by the credits list of over 50 team members, helpers or professional advisers. The major sponsors required the initial book to be accessible and readable by ONCE UPON A TIME book is to be in an 'easy-reading format'. everyone in the community. Local educa- IN ATHERSTONE That has certainly been achieved. But that tionalist Margaret Hughes offered to write Author: Margaret Hughes term belies the depth of research and skill the history, so research information was Publisher: Atherstone Civic Society of presentation, which are what makes the passed to her as it came to light. -

Thoughts About My Tour in Vietnam

CW2 Martin Beckman in the Operations area Delta Company, 227th 1st Cavalry Division, Lai Khe, Republic of Vietnam May, 1970. Thoughts on My Tour of Duty in the Republic of Vietnam By Martin P Beckman Jr. Friday, 07 July, 2006 1 I was born in Anderson, South Carolina and finished High School there. I attended The Citadel and graduated in 1968. I was then drafted and tested to go to flight school with the U.S. Army. For primary helicopter training I was in WOC class 69-19 at Fort Walter’s Texas and afterwards assigned to Fort Rucker, Alabama. There I was promoted to Warrant Officer One and received my Army Aviator “Silver Wings”. I was selected for a Cobra transition at Fort Stewart, Georgia in route to Vietnam. In my th first tour I flew Cobra’s with the Delta Company, 227 Group, 1st Air Calvary Division from August 1969 until August 1970. I later extended my time in Vietnam to fly the UH1 with the 2nd Signal Group. When I arrived in the Republic of Vietnam, we first went to the assignment station where you waited to receive orders to your Unit. I remember all the second tour soldiers and aviators looking very anxiously at the list on the wall next to the orderly room that was posted several times a day. After a few days of waiting my name was on the list for the 1st Calvary st st Division. From there the 1 “Cav” soldiers were bused to the 1 Team Academy at Bien Hoa. -

The Antonine Wall, the Roman Frontier in Scotland, Was the Most and Northerly Frontier of the Roman Empire for a Generation from AD 142

Breeze The Antonine Wall, the Roman frontier in Scotland, was the most and northerly frontier of the Roman Empire for a generation from AD 142. Hanson It is a World Heritage Site and Scotland’s largest ancient monument. The Antonine Wall Today, it cuts across the densely populated central belt between Forth (eds) and Clyde. In The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie, Papers in honour of nearly 40 archaeologists, historians and heritage managers present their researches on the Antonine Wall in recognition of the work Professor Lawrence Keppie of Lawrence Keppie, formerly Professor of Roman History and Wall Antonine The Archaeology at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow University, who spent edited by much of his academic career recording and studying the Wall. The 32 papers cover a wide variety of aspects, embracing the environmental and prehistoric background to the Wall, its structure, planning and David J. Breeze and William S. Hanson construction, military deployment on its line, associated artefacts and inscriptions, the logistics of its supply, as well as new insights into the study of its history. Due attention is paid to the people of the Wall, not just the ofcers and soldiers, but their womenfolk and children. Important aspects of the book are new developments in the recording, interpretation and presentation of the Antonine Wall to today’s visitors. Considerable use is also made of modern scientifc techniques, from pollen, soil and spectrographic analysis to geophysical survey and airborne laser scanning. In short, the papers embody present- day cutting edge research on, and summarise the most up-to-date understanding of, Rome’s shortest-lived frontier. -

Eastern Europe

NAZI PLANS for EASTE RN EUR OPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies SECRET NAZI PLANS for EASTERN EUROPE A Study of Lebensraum Policies hy Ihor Kamenetsky ---- BOOKMAN ASSOCIATES :: New York Copyright © 1961 by Ihor Kamenetsky Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-9850 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY UNITED PRINTING SERVICES, INC. NEW HAVEN, CONN. TO MY PARENTS Preface The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed the climax of imperialistic competition in Europe among the Great Pow ers. Entrenched in two opposing camps, they glared at each other over mountainous stockpiles of weapons gathered in feverish armament races. In the one camp was situated the Triple Entente, in the other the Triple Alliance of the Central Powers under Germany's leadership. The final and tragic re sult of this rivalry was World War I, during which Germany attempted to realize her imperialistic conception of M itteleuropa with the Berlin-Baghdad-Basra railway project to the Near East. Thus there would have been established a transcontinental highway for German industrial and commercial expansion through the Persian Gull to the Asian market. The security of this highway required that the pressure of Russian imperi alism on the Middle East be eliminated by the fragmentation of the Russian colonial empire into its ethnic components. Germany· planned the formation of a belt of buffer states ( asso ciated with the Central Powers and Turkey) from Finland, Beloruthenia ( Belorussia), Lithuania, Poland to Ukraine, the Caucasus, and even to Turkestan. The outbreak and nature of the Russian Revolution in 1917 offered an opportunity for Imperial Germany to realize this plan. -

Antonine Wall - Castlecary Fort

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC170 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90009) Taken into State care: 1961 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2005 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ANTONINE WALL - CASTLECARY FORT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ANTONINE WALL – CASTLECARY FORT BRIEF DESCRIPTION The property is part of the Antonine Wall and contains the remains of a Roman fort and annexe with a stretch of Antonine Wall to the north-east of the fort. The Edinburgh-Glasgow railway cuts across the south section of the fort while modern buildings disturb the north-east corner of the fort and ditch. The Antonine Wall is a linear Roman frontier system of wall and ditch accompanied at stages by forts and fortlets, linked by a road system, stretching for 60km from Bo’ness on the Forth to Old Kilpatrick on the Clyde. It is one of only three linear barriers along the 2000km European frontier of the Roman Empire. These systems are unique to Britain and Germany. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview Archaeological finds indicate the site was used during the Flavian period (AD 79- 87/88). Antonine Wall construction initiated by Emperor Antoninus Pius (AD 138-161) after a successful campaign in AD 139/142 by the Governor of Britain, Lollius Urbicus. -

A Roman Altar from Westerwood on the Antonine Wall by R

A Roman Altar from Westerwood on the Antonine Wall by R. P. Wright The altar here illustrated (PI. 23a) was found3 in ploughing in the spring of 1963 perhaps within r moro , e likel fore f Westerwoowesth e o ty , th jus of to t tAntonine th n do e Walle Th . precise spot could not be determined, but as the altar was unofficial it is more likely to have lain outsiddragges fortboundare e wa aree th th t I ef .fieldth e o d a o t th f ,y o wherrecognise s wa t ei d two days later by Master James Walker and was transferred to Dollar Park Museum. The altar4 is of buff sandstone, 10 in. wide by 25 in. high by 9£ in. thick, and has a rosette with recessed centr focus e plac n stonei e th severas f Th eo .e ha l plough-score bace d th kan n so right side, and was slightly chipped when being hauled off the field, fortunately without any dam- age to the inscription. Much of the lettering was at first obscured by a dark and apparently ferrous concretion, but after some weeks of slow drying this could be brushed off, leaving a slight reddish staininscriptioe Th . n reads: SILVANIS [ET] | QUADRVIS CA[E]|LESTIB-SACR | VIBIA PACATA | FL-VERECV[ND]I | D LEG-VI-VIC | CUM SVIS | V-S-L-M Silvanis Quadr(i)viset Caelestib(us) sacr(wri) Vibia Pacata Fl(avi) Verecundi (uxor) c(enturionis) leg(ionis) VI Vic(tricis) cum suis v(ptum) s(olvii) l(ibens) m(erito) 'Sacred to the Silvanae Quadriviae Caelestes: Vibia Pacata, wife of Flavius Verecundus, centurion Sixte oth f h Legion Victrix, wit r familhhe y willingl deservedld yan y fulfille r vow.he d ' Dedications expressed to Silvanus in the singular are fairly common in Britain,5 as in other provinces.