Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vivid Sydney Media Coverage 1 April-24 May

Vivid Sydney media coverage 1 April-24 May 24/05/2009 Festival sets the city aglow Clip Ref: 00051767088 Sunday Telegraph, 24/05/09, General News, Page 2 391 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes A SPECTACLE of light, sound and creativity is about to showcase Sydney to the world. Vivid Sydney, developed by Events NSW and City of Sydney Council, starts on Tuesday when the city comes alive with the biggest international music and light extravaganza in the southern hemisphere. Keywords: Brian(1), Circular Quay(1), creative(3), Eno(2), festival(3), Fire Water(1), House(4), Light Walk(3), Luminous(2), Observatory Hill(1), Opera(4), Smart Light(1), Sydney(15), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Looking on the bright side Clip Ref: 00051771227 Sunday Herald Sun, 24/05/09, Escape, Page 31 419 words By: Nicky Park Type: Feature Photo: Yes As I sip on a sparkling Lindauer Bitt from New Zealand, my eyes are drawn to her cleavage. I m up on the 32nd floor of the Intercontinental in Sydney enjoying the harbour views, dominated by the sails of the Opera House. Keywords: 77 Million Paintings(1), Brian(1), Eno(5), Festival(8), House(5), Opera(5), Smart Light(1), sydney(10), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Glow with the flow Clip Ref: 00051766352 Sun Herald, 24/05/09, S-Diary, Page 11 54 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes How many festivals does it take to change a coloured light bulb? On Tuesday night Brian Eno turns on the pretty lights for the three-week Vivic Festival. -

Brian Eno: Let There Be Light Gallery

Brian Eno: Let There Be Light Gallery By Dustin Driver Brian Eno paints with light. And his paintings, like Eno’s artwork blossomed in the midst of his musical the medium, shift and dance like free‑flowing jazz career. Still, it was nearly impossible to deliver his solos or elaborate ragas. In fact, they have more in visual creations to the masses. That all changed common with live music than they do with traditional around the turn of the 21st century. “I walked past a artwork. “When I started working on visual work rather posh house in my area with a great big huge again, I actually wanted to make paintings that were screen on the wall and a dinner party going on”, he more like music”, he says. “That meant making visual says. “The screen on the wall was black because work that nonetheless changed very slowly”. Eno has nobody’s going to watch television when they’re been sculpting and bending light into living having a dinner party. Here we have this wonderful, paintings for about 25 years, rigging galleries across fantastic opportunity for having something really the globe with modified televisions, programmed beautiful going on, but instead there’s just a big projectors and three‑dimensional light sculptures. dead black hole on the wall. That was when I determined that I was somehow going to occupy that But Eno isn’t primarily known for his visual art. He’s piece of territory”. known for shattering musical conventions as the keyboardist and audio alchemist for ’70s glam rock Sowing Seeds legends Roxy Music. -

CS-Brian Eno-Eng

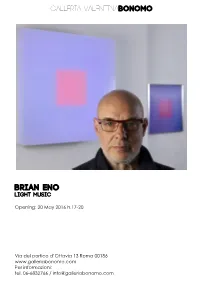

GALLERIA VALENTINABONOMO BRIAN ENO Light Music Opening: 20 May 2016 h.17-20 Via del portico d’Ottavia 13 Roma 00186 www.galleriabonomo.com Per informazioni: tel. 06-6832766 / [email protected] GALLERIA VALENTINABONOMO Friday, 20 May 2016 – September 2016 Press Release The Galleria Valentina Bonomo is delighted to announce the inauguration the exhibition of Brian Eno on Friday, 20 May, 2016 from 6 to 9 pm at via del Portico d’Ottavia 13. The British multi-instrumentalist, composer and producer, Brian Eno, experiments with diverse forms of expression including sculpture, painting and video. Eno is the pioneer of ambient music and generative paintings; he has created soundtracks for numerous films and composed game and atmosphere music. ‘Non-music-music’, as he himself prefers to describe it, has the capacity to be utilized in multiple mediums, intermixing with figurative art to become immersive ‘soundscapes’. By using continuously moving images on multiple monitors, Brian Eno designs endless combination games with infinite varieties of forms, lights and sounds, where not everything is as it seems, and each thing is constantly shifting and changing in a casual and inexorable way, just like in life (ex. 77 Million Paintings). “As long as the screen is considered as just a medium for film or tv, the future is exclusively reserved to an increasing level of hysteria. I am interested in breaking the rigid relationship between the audience and the video: to make it so that the first does not remain seated, but observes the screen as if it were a painting.” Brian Eno For this project, the first of its kind to be realized in a private gallery in Rome, Eno puts together two diverse bodies of work, the light boxes and the speaking flowers. -

Brian Eno's '77 Million Paintings' Is an Artwork That Won't Sit Still

Brian Eno's '77 Million Paintings' is an artwork that won't sit still http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/06/27/... Print This Article Back to Article Brian Eno's '77 Million Paintings' is an artwork that won't sit still Sylvie Simmons, Special to The Chronicle Wednesday, June 27, 2007 "Ah, synesthesia," Brian Eno says by telephone from England. "Vladimir Nabokov had a very severe and interesting form of that -- between characters of the Russian Cyrillic alphabet and color and taste sensations. One particular letter he described as being unquestionably a deep ginger in color with a dark, oily taste. I don't have anything like that." Perhaps not. But Eno admits there are times when he'll listen to one of his self-generating musical compositions and think, "It needs something cold blue over there or it needs something big, soft and brown." His instrumental music -- as fans of his "Ambient" and "Soundtrack" albums will attest -- paints pictures, and his visual art is musical: slow, rhythmic, ambient. When Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno left Roxy Music in 1973, he re-emerged as the founding father of ambient music, embarking on a career in which mainstream projects -- like producing U2 -- were outnumbered by experimental, often computer-based ones as likely to reflect his art school training as his time as a rock keyboard player. This week Eno, 59, presents the U.S. premiere of his "77 Million Paintings," a three-night stand at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Forum. -

Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2008-2009

The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Sir, we have the pleasure of presenting the Annual Report of the Sydney Opera House for the year ended Sydney Opera House 30 June 2009, for presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions 2008/09 Annual Report of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983. Kim Williams AM Richard Evans Chairman Chief Executive Sydney Opera House 2008/09 Annual Report Letter to Minister above Financials 36 Chairman’s Message 4 Financial Statements 38 CEO’s Message 6 Government Reporting 54 Vision & Goals 8 Performance List 66 Key Dates 8 ‘59 Who We Are 9 Our Focus 9 Key Outcomes 2008/09 & Objectives 2009/10 11 Performing Arts 12 Annual Giving 70 Music 14 Contact Information 73 Theatre 16 Opera 18 Index 74 Dance 20 Sponsors inside back cover Danish architect Jørn Utzon Work begins. Young Audiences 22 is announced as the winner of the international design competition by the Hon. JJ (Joe) Cahill. ‘57 Broadening the Experience 24 Building & Environment 26 Corporate Governance 28 The Trust 30 The Executive Team 32 People & Culture 34 sydneyoperahouse.com Where imagination takes you. Cover photography by David Min & Mel Koutchavlis The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Sir, we have the pleasure of presenting the Annual Report of the Sydney Opera House for the year ended Sydney Opera House 30 June 2009, for presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions 2008/09 Annual Report of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983. -

A Generative Ambient Video Engine

Re:Cycle - a Generative Ambient Video Engine Jim Bizzocchi Belgacem Ben Youssef Brian Quan Assistant Professor, School of Assistant Professor, School of Bachelors Student, School of Interactive Arts and Technology Interactive Arts and Technology Interactive Arts and Technology Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University 1-778-782-7508 1-778-869-1162 1-604-767-5803 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Wakiko Suzuki Majid Bagheri Bernhard E. Riecke Bachelors Student, School of Masters Student, School of Assistant Professor, School of Interactive Arts and Technology Interactive Arts and Technology Interactive Arts and Technology Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University Simon Fraser University 1-604-781-9246 1-604-780-4911 1-778-782-8432 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Keywords Re:Cycle is a generative ambient video art piece based on nature ambient video, generative processes, video art, ubiquitous imagery captured in the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Ambient computing, high-definition display, ambient display, "calm" video is designed to play in the background of our lives. An technology, "slow" technology, design ambient video work is difficult to create - it can never require our attention, but must always rewards attention when offered. A 1. AMBIENT VIDEO central aesthetic challenge for this form is that it must also support Ambient Video is video intended to play on the walls in the repeated viewing. Re:Cycle relies on a generative recombinant backgrounds of our lives. In the spirit of Brian Eno's "ambient strategy for ongoing variability, and therefore a higher re- music", Ambient Video must be "as easy to ignore as it is to playability factor. -

Recorded Sound 2011

Recorded Sound Individual Projects In Computer Music - Terry Pender G6630, call # 97748 email: [email protected] 3 Credits Mondays 1 to 4 Room 317, Prentis Hall Office Hours: Tuesday, Wednesday 1 to 3. Course Description As music moves into the next millennium, we are continually confronted by the pervasive use of new music technologies. The world of music is changing rapidly as these technologies open and close doorways of possibility. An appreciation of this shifting technological environment is necessary for active listeners seeking a profound understanding of how music functions in our society. Furthermore, understanding how these technologies function is now almost essential for contemporary composers and theorists working to build an intellectual context for the creation of new musical art. This class will make use of the Columbia University Digital Recording Facility for all of the course work. Class attendance is mandatory - you must attend class; there will be no make up sessions if you miss a day. Missing three classes will lower your final grade by one grade level. Assignments will be due when noted in this syllabus. Lecture notes will be available on the Web through Courseworks. You will be responsible for one final project due on 05/02/11. In addition, the class will work together on a re-creation of a classic Beatles recording. TENTATIVE SYLLABUS Week 1 - 01/24/11 – Introduction to the studio, signing up for studio time online, backing up files. Introduction to recording, digital sound fundamentals. The early days of recording – Thomas Edison, Bill Putnam, Les Paul and the art of innovation. -

Almost Infinite

FROM THE ACADEMY UPFRONT Brian Eno’s 77 Million Paintings at the Fabrica gallery in Brighton, ALMOST England, 2010. INFINITE Brian Eno quiets the mind. amongst the tightly controlled chaos that is city life, a moment of clarity or sanity can be hard to find. Quiet time becomes yet another thing to rigorously schedule into your day. It’s exhausting. But sometimes these moments pop up unexpectedly—you’ll be riding the subway or walking on a relentlessly crowded street, both hyper-aware of your environment and willfully ignoring it at the same damn time. 77 Million Paintings, an audio-visual instal- lation by Brian Eno, is a place where New York- ers can take pause. Showing in the former lo- cation of Café Rouge on West 32nd Street, this marks the New York debut of Eno’s piece, and is also the largest indoor version that’s been produced since the piece premiered in 2006. 77 Million Paintings is a “generative work”—a term coined by Eno 20 years ago to describe art that makes itself as you watch it—that explores vast combinations of visual and sonic elements. Images are chosen at random and then laid on top of one another, so that the final output is a continuous stream of ever-changing material. There aren’t many of the initial “primitives,” as Eno calls the original paintings, but when overlaid four at a time, the number of possible distinct combinations is a whopping 77 million. Eno is fascinated by combinatorial mathe- matics. His idea of generative art takes “a sys- tems approach to making art,” as he explained during his recent lecture at Red Bull Music Academy, “where essentially you are creating a conceptual machine, which then keeps produc- ing stuff.” This effectively ensures that the same image or soundscape never repeats. -

ŸƑ螱Ʃ·ļšè¯º Éÿ³æ

å¸ƒèŽ±æ© Â·ä¼Šè¯º 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & æ—¶é— ´è¡¨) Another Green World https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/another-green-world-771427/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ambient-1%3A-music-for-airports- Ambient 1: Music for Airports 127100/songs Thursday Afternoon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/thursday-afternoon-7799409/songs Wrong Way Up https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/wrong-way-up-128940/songs Before and After Science https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/before-and-after-science-676884/songs Ambient 4: On Land https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ambient-4%3A-on-land-958618/songs Discreet Music https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/discreet-music-2058212/songs Music for Films https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/music-for-films-39267/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/apollo%3A-atmospheres-and- Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks soundtracks-3282479/songs Cluster & Eno https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cluster-%26-eno-2980401/songs After The Heat https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/after-the-heat-4690656/songs Another Day on Earth https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/another-day-on-earth-279977/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fourth-world%2C-vol.-1%3A-possible- Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics musics-8135341/songs Nerve Net https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/nerve-net-3492507/songs Music for Films III https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/music-for-films-iii-6941772/songs January 07003: Bell -

Senza Titolo 9

www.Timeoutintensiva.it OTT 2008, Recensioni-B.Eno. N° 7 Brian ENO: Discografia e filmografia (colonne sonore): Discografia * (1972) Roxy Music (da Roxy Music) * (1973) For Your Pleasure (da Roxy Music) * (1973) No Pussyfooting (con Robert Fripp) * (1973) Portsmouth Sinfonia Plays the Popular Classics (con la Portsmouth Sinfonia) * (1973) Here Come The Warm Jets * (1974) Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) * (1975) Evening Star (con Robert Fripp) * (1975) Another Green World * (1975) Discreet Music * (1977) Cluster & Eno (con i Cluster) * (1978) Before and After Science * (1978) Ambient #1 / Music for Airports * (1978) Music for Films * (1978) After the Heat (con Roedelius e Dieter Moebius, alias Cluster) * (1979) In a Land of Clear Colors (con Pete Sinfield che recita un racconto di Robert Sheckley) * (1980) Ambient #2 / The Plateaux of Mirror (con Harold Budd) * (1980) Fourth World, Vol. 1: Possible Musics (con Jon Hassell) * (1980) Ambient #3 / Day of Radiance (da Laraaji con Eno producing) * (1981) My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (con David Byrne) * (1982) Ambient #4 / On Land * (1983) Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks * (1984) The Pearl (con Harold Budd) * (1985) Thursday Afternoon (per una galleria di arte video) * (1985) Hybrid (con Daniel Lanois e Michael Brook) * (1988) Music from Films III (con Daniel Lanois, Michael Brook e Roger Eno) * (1989) Textures (raccolta di brani editi e inediti riservata ai film-makers) * (1990) The Shutov Assembly (All Saints Records) * (1990) Wrong Way Up (con John Cale) (All Saints Records) * (1992) Nerve Net (All Saints Records) * (1993) Neroli (All Saints Records) * (1995) Spinner (con Jah Wobble) (All Saints Records) * (1995) Original Soundtracks No. -

Issue3-Autumn2017

ISSN 2515-981X Music on Screen From Cinema Screens to Touchscreens Part II Edited by Sarah Hall James B. Williams Musicology Research Issue 3 Autumn 2017 This page is left intentionally blank. ISSN 2515-981X Music on Screen From Cinema Screens to Touchscreens Part II Edited by Sarah Hall James B. Williams Musicology Research Issue 3 Autumn 2017 MusicologyResearch The New Generation of Research in Music Autumn 2017 © ISSN 2515-981X MusicologyResearch No part of this text, including its cover image, may be reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or others means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from MusicologyResearch and its contributors. MusicologyResearch offers a model whereby the authors retain the copyright of their contributions. Cover Image ‘Now’. Contemporary Abstract Painting, Acrylic, 2016. Used with permission by artist Elizabeth Chapman. © Elizabeth Chapman. http://melizabethchapman.artspan.com http://melizabethchapman.blogspot.co.uk Visit the MusicologyResearch website at http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk for this issue http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/julianahodkinson-creatingheadspace http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/royaarab- howmenbecamethesoleadultdancingsingersiniranianfilms http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/fernandobravo- neuralsystemsunderlyingmusicsaffectiveimpactinfilm http://www.musicologyresearch.co.uk/publications/enochjacobus-chooseyourownaudioventuresoundtrack -

THE AVASTAR Staff In-World Can Follow RL Tennis Major, the the Action a Short Time Australian Open

ISSUE 28 | 06-29-2007 WWW.THE-AVASTAR.COM FREE EVERY FRIDAY L$150 COPY NEWS p.2-11 Phil suffers speech disaster at birthday bash BUSINESS p.13 The secrets to Rendezvous’ success STYLE p.16-19 Dress to impress with black and white fashion AVASTAR OF THE WEEK p.31 Blogger Noemi Despres reveals all ANGRY DESIGNERS CONFRONT ‘CHEAT’ SEE PAGE 7 WIMBLEDON: BY CARRIE SODWIND SECOND Life is a “soap opera“ SL SERVES which could see its residents reject “messy“ relation- UP AN ACE ships in real life, says a respected British scientist. FULL STORY SEE PAGE 3 PAGES 4 & 5 0 NEWS Jun. 29, 2007 Jun. 29, 2007 NEWS 0 INSIDE OPINION NUMBERSOF THE WEEK GAME SET MATCH, IBM! “Unless Linden Lab is ... the number of Lindens listed as part of the new in-world owned by eBay, I re- 10 concierge service that launched this week FORTY-LOVE: Live tennis on centre court ally don‘t see ... is the amount of L$ won by Joshua Culdesac and Piper Pitney the justifi- in a competition to redevelop a part of RL Paris. cation for 270,000 their crack- ... changes suggested by residents were made to the viewer in ing down on users 80 the past month, all from the SL open source community. who buy L$ from eBay.“ WHO’S THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL? ADIA CLARY p.9 FOLLOW THE WIMBLEDON ACTION ‘live’ in sl “SL may be the logi- By COYNE NAGY cal extension of social IBM have served up a TENNIS BEAUTY: A Russian resident? networking and on- treat for tennis fans line dating, replacing by recreating all the 2D profiles with 3D action from the fa- avatars in an interac- mous centre court at tive environment.