Issue3-Autumn2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vivid Sydney Media Coverage 1 April-24 May

Vivid Sydney media coverage 1 April-24 May 24/05/2009 Festival sets the city aglow Clip Ref: 00051767088 Sunday Telegraph, 24/05/09, General News, Page 2 391 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes A SPECTACLE of light, sound and creativity is about to showcase Sydney to the world. Vivid Sydney, developed by Events NSW and City of Sydney Council, starts on Tuesday when the city comes alive with the biggest international music and light extravaganza in the southern hemisphere. Keywords: Brian(1), Circular Quay(1), creative(3), Eno(2), festival(3), Fire Water(1), House(4), Light Walk(3), Luminous(2), Observatory Hill(1), Opera(4), Smart Light(1), Sydney(15), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Looking on the bright side Clip Ref: 00051771227 Sunday Herald Sun, 24/05/09, Escape, Page 31 419 words By: Nicky Park Type: Feature Photo: Yes As I sip on a sparkling Lindauer Bitt from New Zealand, my eyes are drawn to her cleavage. I m up on the 32nd floor of the Intercontinental in Sydney enjoying the harbour views, dominated by the sails of the Opera House. Keywords: 77 Million Paintings(1), Brian(1), Eno(5), Festival(8), House(5), Opera(5), Smart Light(1), sydney(10), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Glow with the flow Clip Ref: 00051766352 Sun Herald, 24/05/09, S-Diary, Page 11 54 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes How many festivals does it take to change a coloured light bulb? On Tuesday night Brian Eno turns on the pretty lights for the three-week Vivic Festival. -

Sonification As a Means to Generative Music Ian Baxter

Sonification as a means to generative music By: Ian Baxter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts & Humanities Department of Music January 2020 Abstract This thesis examines the use of sonification (the transformation of non-musical data into sound) as a means of creating generative music (algorithmic music which is evolving in real time and is of potentially infinite length). It consists of a portfolio of ten works where the possibilities of sonification as a strategy for creating generative works is examined. As well as exploring the viability of sonification as a compositional strategy toward infinite work, each work in the portfolio aims to explore the notion of how artistic coherency between data and resulting sound is achieved – rejecting the notion that sonification for artistic means leads to the arbitrary linking of data and sound. In the accompanying written commentary the definitions of sonification and generative music are considered, as both are somewhat contested terms requiring operationalisation to correctly contextualise my own work. Having arrived at these definitions each work in the portfolio is documented. For each work, the genesis of the work is considered, the technical composition and operation of the piece (a series of tutorial videos showing each work in operation supplements this section) and finally its position in the portfolio as a whole and relation to the research question is evaluated. The body of work is considered as a whole in relation to the notion of artistic coherency. This is separated into two main themes: the relationship between the underlying nature of the data and the compositional scheme and the coherency between the data and the soundworld generated by each piece. -

David Bowie's Urban Landscapes and Nightscapes

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 17 | 2018 Paysages et héritages de David Bowie David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.13401 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Jean Du Verger, “David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text”, Miranda [Online], 17 | 2018, Online since 20 September 2018, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/13401 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.13401 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text 1 David Bowie’s urban landscapes and nightscapes: A reading of the Bowiean text Jean Du Verger “The Word is devided into units which be all in one piece and should be so taken, but the pieces can be had in any order being tied up back and forth, in and out fore and aft like an innaresting sex arrangement. This book spill off the page in all directions, kaleidoscope of vistas, medley of tunes and street noises […]” William Burroughs, The Naked Lunch, 1959. Introduction 1 The urban landscape occupies a specific position in Bowie’s works. His lyrics are fraught with references to “city landscape[s]”5 and urban nightscapes. The metropolis provides not only the object of a diegetic and spectatorial gaze but it also enables the author to further a discourse on his own inner fragmented self as the nexus, lyrics— music—city, offers an extremely rich avenue for investigating and addressing key issues such as alienation, loneliness, nostalgia and death in a postmodern cultural context. -

There's an App for That!

There’s an App for That! FPSResources.com Business Bob Class An all-in-one productivity app for instructors. Clavier Companion Clavier Companion has gone digital. Now read your favorite magazine from your digital device. Educreations Annotate, animate and narrate on interactive whiteboard. Evernote Organizational app. Take notes, photos, lists, scan, record… Explain Everything Interactive whiteboard- create, rotate, record and more! FileApp This is my favorite app to send zip files to when downloading from my iPad. Reads PDF, Office, plays multi-media contents. Invoice2go Over 20 built in invoice styles. Send as PDF’s from your device; can add PayPal buttons. (Lite version is free but only lets you work with three invoices at a time.) Keynote Macs version of PowerPoint. Moosic Studio Studio manager app. Student logs, calendar, invoicing and more! Music Teachers Helper If you subscribe to MTH you can now log in and do your business via your iPhone or iPad! Notability Write in PDF’s and more! Pages Word Processing App PayPal Here OR Square Card reader app. Reader is free, need a PayPal account. Ranging from 2.70 (PayPal) - 2.75% (Square) per swipe Piano Bench Magazine An awesome piano teacher magazine you can read from your iPad and iPhone! PDF Expert Reads, annotates, mark up and edits PDF documents. Remind Formerly known as Remind 101, offers teachers a free, safe and easy to use way to instantly text students and parents. Skitch Mark up, annotate, share and capture TurboScan or TinyScan Pro or Scanner Pro Scan and email jpg or pdf files. Easy! Week Calendar Let’s you color code events. -

SPILL Study Room Guide

Study Room Guide SPILL STUDY BOXES November 2012 In 2012 SPILL Festival of Performance, Ipswich invited the Agency to create a special pop-up version of the Study Room for the SPILL Study Café. For the Study Café the Agency curated a selection of 20 Study Boxes each containing a range of hand picked DVDs, books and other materials around specific themes that we believed would inspire, excite and intrigue artists and audiences attending the Festival in Ipswich. The Study Boxes reflected the work of a huge range of UK and international artists and represent a diversity of themes including issues of identity politics in performance, the explicit body in performance, large scale performance, sound and music in performance, activism and performance, ritual and magic, large scale performance, strange theatre, life long performances, participatory performance, critical writing, non Western performance, do it yourself, trash performance, and many more. Each Study Box contained between four and eight items and could be used for a quick browse or for a day-long study. “Completely brilliant.” (Andy Field, Forest Fringe) “The openness and democracy of the Study Café is essential in a festival where questions of access are so present. It illustrates the need to offer the work of artists up for wider consumption rather than limited to the tight circle of those in the know. Proximity cuts both ways, and as a group of performance makers, it falls to artists, writers and enthusiasts to collapse these referential gaps between audiences. As funding shrinks and organisations falter, the ability to bring those without any history of performance in, to speak to issues outside of the intellectual concerns of Live Art becomes essential for the survival of the form and any community around it. -

26. April 2015 Ausstellung 22. April - 26

22. April - 26. April 2015 Ausstellung 22. April - 26. Mai 2015 "Now" CONTENT Imprint 24 Words of Welcome 26 FilmFestSpezial-TV 34 Film- & Videokommission 35 INTERNATIONALE AUSWAHL 36 Being There 36 Curious Correlations 40 Ecstatic Realism 44 Freestyle 48 Gold Diggers 52 Home Made Video 55 Life - Art - Balance 56 New Order 59 Oblique Strategies 63 Of Hope And Glory 67 Orgy of the Devil 68 Parandroids 69 Past's Present 72 (Re)Visionaries 74 State of Passage 76 Through Time And Space 78 Tick Tack Ton 80 IRONY Ash & Money 86 Displaced Persons 87 A Pigeon Sits on a Branch Reflecting on Existence 88 Jedes Bild ist ein leeres Bild 89 The Yes Men Are Revolting 90 Werk 91 RETROSPECTIVE 92 Irony as Subversive Intervention 92 La vie en rose 93 Film als Message 98 The Crisis of Today is the Joke of Tomorrow 101 Wir haben's doch! 104 Zaun schärfen in Dunkeldeutschland oder Das tätowierte Schwein ohne Sonnenschein 108 MEDIA CAMPUS 110 A Hard Day's Life 110 Alienation 114 Connexions 118 Family Affairs 122 No Place Like Home 125 MEDIA CAMPUS SPECIAL 128 Multimedia University in Malaysia 128 EXHIBITION IRONY 130 Ironie in der Medienkunst - Subversive Interventionen 130 Oferta Especial - Ruben Aubrecht 133 Loophole for all - Paolo Cirio 134 This Unfortunate Thing Between Us (TUTBU) - Phil Collins 136 Autoscopy for Dummies - Antonin De Bemels 138 22 Dear Lorde - Emily Vey Duke, Cooper Battersby 139 Justified Beliefs - Christian Falsnaes 140 Rise - Christian Falsnaes 141 Bigasso Baby - annette hollywood 142 Casting Jesus - Christian Jankowski 143 Forbidden Blood - Istvan Kantor 144 Turmlaute 2: Watchtower - georg klein 146 Van Gogh Variationen - Marcello Mercado 147 TSE (Out) - Roee Rosen 148 The Wall - Egill Sæbjörnsson 150 Leaving A User's Manual - *Iron A Hare * Leave A Desire * Climb Up Hight - Meggie Schneider 152 EXHIBITION MEDIA CAMPUS 154 KHM_section - Kooperation mit Prof. -

Oblique Strategies

Remove specifics and convert to ambiguities Think of the radio Don't be frightened of clichés Allow an easement (an easement is the abandonment of a stricture) What is the reality of the situation? Simple subtraction Are there sections? Consider transitions Remove specifics and convert to ambiguities Turn it upside down Go slowly all the way round the outside Oblique Strategies © 1975, 1978, 1979 Brian Eno/Peter Schmidt PDF file created by Matthew Davidson http://www.stretta.com A line has two sides Infinitesimal gradations Make an exhaustive list of everything you might do Change instrument roles and do the last thing on the list Into the impossible Accretion Ask people to work against their better judgment Disconnect from desire Take away the elements in order Emphasize repetitions of apparent non-importance Don't be afraid of things because they're easy to do Is there something missing? Don't be frightened to display your talents Use unqualified people Breathe more deeply How would you have done it? Honor thy error as a hidden intention Emphasize differences Only one element of each kind Do nothing for as long as possible Bridges -build Water -burn You don't have to be ashamed of using your own ideas Make a sudden, destructive unpredictable action; incorporate Consult other sources Tidy up Do the words need changing? Use an unacceptable color Ask your body Humanize something free of error Use filters Balance the consistency principle with the inconsistency principle Fill every beat with something Do nothing for as long as possible -

Brian Eno: Let There Be Light Gallery

Brian Eno: Let There Be Light Gallery By Dustin Driver Brian Eno paints with light. And his paintings, like Eno’s artwork blossomed in the midst of his musical the medium, shift and dance like free‑flowing jazz career. Still, it was nearly impossible to deliver his solos or elaborate ragas. In fact, they have more in visual creations to the masses. That all changed common with live music than they do with traditional around the turn of the 21st century. “I walked past a artwork. “When I started working on visual work rather posh house in my area with a great big huge again, I actually wanted to make paintings that were screen on the wall and a dinner party going on”, he more like music”, he says. “That meant making visual says. “The screen on the wall was black because work that nonetheless changed very slowly”. Eno has nobody’s going to watch television when they’re been sculpting and bending light into living having a dinner party. Here we have this wonderful, paintings for about 25 years, rigging galleries across fantastic opportunity for having something really the globe with modified televisions, programmed beautiful going on, but instead there’s just a big projectors and three‑dimensional light sculptures. dead black hole on the wall. That was when I determined that I was somehow going to occupy that But Eno isn’t primarily known for his visual art. He’s piece of territory”. known for shattering musical conventions as the keyboardist and audio alchemist for ’70s glam rock Sowing Seeds legends Roxy Music. -

Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies Dil, Edebiyat Ve

Lit ra Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies Dil, Edebiyat ve Kültür Araştırmaları Dergisi Volume: 31 | Number: 1 E-ISSN: 2602-2117 Litera: Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies Litera: Dil, Edebiyat ve Kültür Araştırmaları Dergisi Volume: 31 | Number: 1, 2021 E-ISSN: 2602-2117 Indexing and Abstracting Web of Science Emerging Sources Citation Index (ESCI) MLA International Bibliography, TÜBİTAK-ULAKBİM TR Index, SOBİAD Litera: Journal of Language, Literature and Culture Studies Litera: Dil, Edebiyat ve Kültür Araştırmaları Dergisi Volume: 31 | Number: 1, 2021 E-ISSN: 2602-2117 Owner / Sahibi Prof. Dr. Hayati DEVELİ Istanbul University, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul - Turkey İstanbul Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, İstanbul - Türkiye Responsible Manager / Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü Prof. Dr. Mahmut KARAKUŞ Istanbul University, Faculty of Letters, Istanbul - Turkey İstanbul Üniversitesi, Edebiyat Fakültesi, İstanbul - Türkiye Correspondence Address / Yazışma Adresi Istanbul University, Faculty of Letters, Department of Western Languages and Literatures 34134, Laleli, Istanbul - Turkey Phone / Telefon: +90 (212) 455 57 00 / 15900 e-mail: [email protected] http://litera.istanbul.edu.tr Publisher / Yayıncı Istanbul University Press / İstanbul Üniversitesi Yayınevi Istanbul University Central Campus, 34452 Beyazit, Fatih / Istanbul - Turkey Phone / Telefon: +90 (212) 440 00 00 Printed by / Baskı İlbey Matbaa Kağıt Reklam Org. Müc. San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. 2. Matbaacılar Sitesi 3NB 3 Topkapı / Zeytinburnu, Istanbul - Turkey www.ilbeymatbaa.com.tr Sertifika No: 17845 Authors bear responsibility for the content of their published articles. Dergide yer alan yazılardan ve aktarılan görüşlerden yazarlar sorumludur. The publication languages of the journal are German, French, English, Spanish, Italian and Turkish. Yayın dili Almanca, Fransızca, İngilizce, İspanyolca, İtalyanca ve Türkçe’dir. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE JAIME MANUEL GARCÍA BOLAO, BA, BA, BS, NCTM, FRSM TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA, MAY 2020 JAIME MANUEL GARCÍA BOLAO, BA, BA, BS, NCTM, FRSM PAGE 2 JAIME MANUEL GARCÍA BOLAO, BA, BA, BS, NCTM, FRSM Professional Address: 2367 May Apple Ct, Tallahassee, Fl, 32308 United States of America | +1 850-322-8746 | [email protected] Citizenship: United States of America, Kingdom of Spain TEACHING PHILOSOPHY Teaching and learning are among the most important activities people engage in. Our capacity to gain wisdom makes us human. A music instructor should be dedicated to helping his students gain wisdom. Careful, loving teaching and learning are essential to music. Gaining wisdom is no small task; it takes a lifetime. The quest for knowledge is among the primary driving forces in my life; my passion for learning fuels my pursuit of teaching excellence. I aspire to be a great teacher because in it is the power to impart knowledge, influence thinking and ultimately create positive change in the world. JAIME MANUEL GARCÍA BOLAO, BA, BA, BS, NCTM, FRSM PAGE 3 Music should form an integral part of the development of any young mind. It utilizes much of the brain, making it valuable in all areas of development: academic, emotional, physical and spiritual. Practicing a musical instrument teaches lessons beyond merely the ability to play; it imparts discipline, patience and dedication. Moreover, there is no age limit to enjoying or engaging in music. Learning music is a life-long endeavor. Students may not be able to take lessons throughout their lives, but they can remain music lovers and stay musically active. -

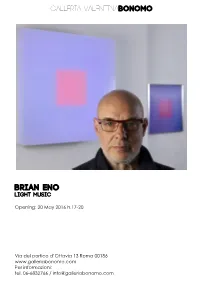

CS-Brian Eno-Eng

GALLERIA VALENTINABONOMO BRIAN ENO Light Music Opening: 20 May 2016 h.17-20 Via del portico d’Ottavia 13 Roma 00186 www.galleriabonomo.com Per informazioni: tel. 06-6832766 / [email protected] GALLERIA VALENTINABONOMO Friday, 20 May 2016 – September 2016 Press Release The Galleria Valentina Bonomo is delighted to announce the inauguration the exhibition of Brian Eno on Friday, 20 May, 2016 from 6 to 9 pm at via del Portico d’Ottavia 13. The British multi-instrumentalist, composer and producer, Brian Eno, experiments with diverse forms of expression including sculpture, painting and video. Eno is the pioneer of ambient music and generative paintings; he has created soundtracks for numerous films and composed game and atmosphere music. ‘Non-music-music’, as he himself prefers to describe it, has the capacity to be utilized in multiple mediums, intermixing with figurative art to become immersive ‘soundscapes’. By using continuously moving images on multiple monitors, Brian Eno designs endless combination games with infinite varieties of forms, lights and sounds, where not everything is as it seems, and each thing is constantly shifting and changing in a casual and inexorable way, just like in life (ex. 77 Million Paintings). “As long as the screen is considered as just a medium for film or tv, the future is exclusively reserved to an increasing level of hysteria. I am interested in breaking the rigid relationship between the audience and the video: to make it so that the first does not remain seated, but observes the screen as if it were a painting.” Brian Eno For this project, the first of its kind to be realized in a private gallery in Rome, Eno puts together two diverse bodies of work, the light boxes and the speaking flowers. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Numbers Anderson, Reid, 187 back phrasing, 33 Anderson, Sheila E., 267–268 Ball, Ernie, 188 8/12/16/24-bar blues, 146–147 Andrews, Julie, 250 ballad form, 140 anticipation, 80 Bandcamp, 215, 272 A appoggiatura, 78–79 Bartók, Béla, 57, 124, 127, arch form: ABCBA, 142 142, 153 A (verse), 148–149 “Arianna” (Monteverdi), 11 bass, 174, 187–188 a cappella, 11 Armstrong, Louis, 194 bass flute, 173 Ableton, 17, 232 arranging instruments, bassoon, 173–174 accidentals, 97 179–183, 259–260 Baxter, Les, 270 accordion, 193 ASCAP (American Society of The Beach Boys, 148 acoustic instruments Composers, Authors & The Beatles, 132, 148 Publishers), 217 bass guitar, 188 Bechet, Sidney, 194 atonal music, 150–154 electronic instruments Beethoven, L. van vs., 25 Audiosparx, 261 lyrics and, 131–132 guitar, 189–190 augmented chords, 103 pieces by, 31, 71 action drive, 123 authentic cadences, 109 rhythms and, 31–32 Adagio, 30 avant garde, 57 symphonies by, 144 Aeolian mode, 60, 133 Azarm, Ben, 238 beginning of songs, 133–135, air form, 140 225–226 Albini, Steve, 260 B bellows, 193 Allegro, 30 B (chorus), 149 bending, 245–246 Alpert, Herb, 127 B flat clarinet, 164–165, 166 Berg, Alban, 144 alto flute, 162–163 B flat trumpet, 163–164 Biafra, Jello, 270 amen cadence, 109 Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel, binary form: AB, 140 American Composers 78, 201 Bizet, G., 20 Forum, 218 Bach, Johann Christian, 201 block harmony, 197 American Mavericks (Key, Bach, Johann Sebastian blues, 146–147 Roethe), 269 COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL analysis of, 267 BMI (Broadcast Music American