Thinking Inside the Box: Brian Eno, Music, Movement and Light THINKING INSIDE the BOX Brian Eno, Music, Movement and Light

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vivid Sydney Media Coverage 1 April-24 May

Vivid Sydney media coverage 1 April-24 May 24/05/2009 Festival sets the city aglow Clip Ref: 00051767088 Sunday Telegraph, 24/05/09, General News, Page 2 391 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes A SPECTACLE of light, sound and creativity is about to showcase Sydney to the world. Vivid Sydney, developed by Events NSW and City of Sydney Council, starts on Tuesday when the city comes alive with the biggest international music and light extravaganza in the southern hemisphere. Keywords: Brian(1), Circular Quay(1), creative(3), Eno(2), festival(3), Fire Water(1), House(4), Light Walk(3), Luminous(2), Observatory Hill(1), Opera(4), Smart Light(1), Sydney(15), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Looking on the bright side Clip Ref: 00051771227 Sunday Herald Sun, 24/05/09, Escape, Page 31 419 words By: Nicky Park Type: Feature Photo: Yes As I sip on a sparkling Lindauer Bitt from New Zealand, my eyes are drawn to her cleavage. I m up on the 32nd floor of the Intercontinental in Sydney enjoying the harbour views, dominated by the sails of the Opera House. Keywords: 77 Million Paintings(1), Brian(1), Eno(5), Festival(8), House(5), Opera(5), Smart Light(1), sydney(10), Vivid(6), vividsydney(1) Glow with the flow Clip Ref: 00051766352 Sun Herald, 24/05/09, S-Diary, Page 11 54 words By: None Type: News Item Photo: Yes How many festivals does it take to change a coloured light bulb? On Tuesday night Brian Eno turns on the pretty lights for the three-week Vivic Festival. -

Sonification As a Means to Generative Music Ian Baxter

Sonification as a means to generative music By: Ian Baxter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts & Humanities Department of Music January 2020 Abstract This thesis examines the use of sonification (the transformation of non-musical data into sound) as a means of creating generative music (algorithmic music which is evolving in real time and is of potentially infinite length). It consists of a portfolio of ten works where the possibilities of sonification as a strategy for creating generative works is examined. As well as exploring the viability of sonification as a compositional strategy toward infinite work, each work in the portfolio aims to explore the notion of how artistic coherency between data and resulting sound is achieved – rejecting the notion that sonification for artistic means leads to the arbitrary linking of data and sound. In the accompanying written commentary the definitions of sonification and generative music are considered, as both are somewhat contested terms requiring operationalisation to correctly contextualise my own work. Having arrived at these definitions each work in the portfolio is documented. For each work, the genesis of the work is considered, the technical composition and operation of the piece (a series of tutorial videos showing each work in operation supplements this section) and finally its position in the portfolio as a whole and relation to the research question is evaluated. The body of work is considered as a whole in relation to the notion of artistic coherency. This is separated into two main themes: the relationship between the underlying nature of the data and the compositional scheme and the coherency between the data and the soundworld generated by each piece. -

Alleged KA Sexual Assault Goes Unprosecuted

ln Section 2 In Sports An Associated Collegiate Press Sick kids Do Hens Four-Star All-American Newspaper make the get a medicinal grade? - page BlO education page B 1 I Non-profit Org. FREE U.S. Postage Pa1d FRIDAY Newark, DE Volume 122, Number 40 250 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 Permit No. 26 March 8, 1996 Alleged KA sexual assault goes unprosecuted conviction is wrong." are taken to the attorney general's before reporting an assault. such as the one previously alleged, Delay in reporting the incident cited as Speaking hypothetically , office to decide if there is enough "What does it tell men?" she we do believe that the attorney reason for dismissal; Sigma Kappa says Pederson said, if there is a evidence to prosecute, whereas the asked, her face flushed. "Nothing. If general's decision is a fair one, significant gap between the rape and university's judicial system is I were a guy, I would fear nothing.'' clearly made after carefully decision tells men to 'fear nothing' its reporting, you not only lose the designed to deal with non-criminal Interfraternity Council President investigating the matter in full." physical evidence, but it gives those code of conduct violations on Bill Werde disagreed , saying the When asked to respond to the BY KIM WALKER said. involved a chance to corroborate r------- campus. case conveys the opposite message. charge that Sigma Kappa was Managing Nt:ws Editor ··we did not find enough their stories. Dana Gereghty, "The message [the decision] sent punished while the former fraternity evidence that could lead to a The former Kappa Alpha Order Dean of Students Timothy F. -

Brian Eno: Let There Be Light Gallery

Brian Eno: Let There Be Light Gallery By Dustin Driver Brian Eno paints with light. And his paintings, like Eno’s artwork blossomed in the midst of his musical the medium, shift and dance like free‑flowing jazz career. Still, it was nearly impossible to deliver his solos or elaborate ragas. In fact, they have more in visual creations to the masses. That all changed common with live music than they do with traditional around the turn of the 21st century. “I walked past a artwork. “When I started working on visual work rather posh house in my area with a great big huge again, I actually wanted to make paintings that were screen on the wall and a dinner party going on”, he more like music”, he says. “That meant making visual says. “The screen on the wall was black because work that nonetheless changed very slowly”. Eno has nobody’s going to watch television when they’re been sculpting and bending light into living having a dinner party. Here we have this wonderful, paintings for about 25 years, rigging galleries across fantastic opportunity for having something really the globe with modified televisions, programmed beautiful going on, but instead there’s just a big projectors and three‑dimensional light sculptures. dead black hole on the wall. That was when I determined that I was somehow going to occupy that But Eno isn’t primarily known for his visual art. He’s piece of territory”. known for shattering musical conventions as the keyboardist and audio alchemist for ’70s glam rock Sowing Seeds legends Roxy Music. -

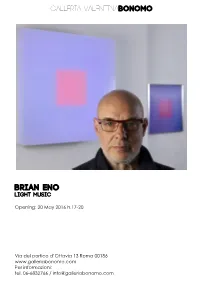

CS-Brian Eno-Eng

GALLERIA VALENTINABONOMO BRIAN ENO Light Music Opening: 20 May 2016 h.17-20 Via del portico d’Ottavia 13 Roma 00186 www.galleriabonomo.com Per informazioni: tel. 06-6832766 / [email protected] GALLERIA VALENTINABONOMO Friday, 20 May 2016 – September 2016 Press Release The Galleria Valentina Bonomo is delighted to announce the inauguration the exhibition of Brian Eno on Friday, 20 May, 2016 from 6 to 9 pm at via del Portico d’Ottavia 13. The British multi-instrumentalist, composer and producer, Brian Eno, experiments with diverse forms of expression including sculpture, painting and video. Eno is the pioneer of ambient music and generative paintings; he has created soundtracks for numerous films and composed game and atmosphere music. ‘Non-music-music’, as he himself prefers to describe it, has the capacity to be utilized in multiple mediums, intermixing with figurative art to become immersive ‘soundscapes’. By using continuously moving images on multiple monitors, Brian Eno designs endless combination games with infinite varieties of forms, lights and sounds, where not everything is as it seems, and each thing is constantly shifting and changing in a casual and inexorable way, just like in life (ex. 77 Million Paintings). “As long as the screen is considered as just a medium for film or tv, the future is exclusively reserved to an increasing level of hysteria. I am interested in breaking the rigid relationship between the audience and the video: to make it so that the first does not remain seated, but observes the screen as if it were a painting.” Brian Eno For this project, the first of its kind to be realized in a private gallery in Rome, Eno puts together two diverse bodies of work, the light boxes and the speaking flowers. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

NEWSLETTER August 2016

NEWSLETTER August 2016 Volume 11 Issue #08 CLUB NEWS August 2 SAOS We introduced Suzanne Susko as our AOS Representative. Meeting Suzanne explained the benefits of AOS membership by Janis Croft, secy@ including discounts and free admission to over 300 gardens staugorchidsociety.org as well as the very informative culture sheets provided on the member’s side of the AOS website. Welcome and Thanks. President Bob Schimmel Orchid Events. There are no Florida orchid shows in opened the meeting at 7:15 the next two months. The Odom’s 6th Annual Cattleya pm with 65 attendees. Bob Symposium will be held in Fort Pierce from August 5 and 6. thanked Jeannette Smith, Leslie Brickell and Elaine Show Table Review. Courtney Hackney stated that the Hardy for the refreshments table demonstrates that there are summer blooming orchids while reminding all to which are primarily the Bifoliate Cattleyas from Brazil. He Alan Koch drop a dollar in the jar. pointed out the Cattleya leopoldii as a prime example. He We welcomed two new then discussed the Lc. Maui Plum ‘Volcano Queen’ (whose members, Joan and Charles Delony who joined at the one parent is Cattleya leopoldii) that has been bred for meeting, along with eight guests. cluster of flowers and likes high light. Next was the pure Our Membership Veep, Linda Stewart recognized our white Cattleya Hawaiian Wedding Song ‘Virgin’ which was several August birthday people with a free raffle ticket. produced in the 60’s. Hybridizers used the large corsage Bob informed all that the Best of Show voting would occur type varieties along with the smaller flower size species to between the Show Table discussion and program and produce a flower that worked much better as a corsage. -

FWWH Revised Songbook ―This Camp Was Built to Music Therefore Built Forever

FWWH Revised Songbook Revised Summer 2011 ―This camp was built to music therefore built forever‖ These are the songs sung by Four Winds and Westward Ho campers – songs that have expressed their interests and ideals through the years. As you sing the songs again, may they recall memories of sunny days, and some misty and rainy ones too, of sailing on sparkling blue water, of cantering along leafy trails, of exploring the beach when the tide is out. May these songs remind you of unexpected adventure, and of friendships formed through the sharing of Summer days, working and playing together. 1 Index of songs A Gypsy‘s Life…………………………………………………….7 A Junior Song……………………………………………………..7 A Walking Song………………………………….…….………….8 Across A Thousand Miles of Sea…………..………..…………….8 Ah, Lovely Meadows…………………………..……..…………...9 All Hands On Deck……………………………………..……..…10 Another Fall…………………………………...…………………10 The Banks of the Sacramento…………………………………….…….12 Big Foot………………………………………..……….………………13 Bike Song……………………………………………………….…..…..14 Blow the Man Down…………………………………………….……...14 Blowin‘ In the Wind…………………………………………………....15 Boy‘s Grace…………………………………………………………….16 Boxcar……………………………………………………….…..……..16 Canoe Round…………………………………………………...………17 Calling Out To You…………………………………………………….17 Canoe Song……………………………………………………………..18 Canoeing Song………………………………………………………….18 Cape Anne………………………………………………...……………19 Carlyn…………………………………………………………….…….20 Changes………………………………………………………………...20 Christmas Night………………………………………………………...21 Christmas Song…………………………………………………………21 The Circle Game……………………………………………………..…22 -

Aesthetic Humanism: the Radical Romantic Vision of Blake and Byron

Aesthetic Humanism: The Radical Romantic Vision of Blake and Byron By John William Davies, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in English Spring 2013 Copyright By John William Davies 2013 Aesthetic Humanism: The Radical Romantic Vision ofBlake and Byron By John William Davies This thesis has been accepted on behalf ofthe Department ofEnglish by their supervisory committee: Dr. Susan Stafinbil Committee Chair Dr. Steven Frye Aesthetic Humanism: The Radical Romantic Vision of Blake and Byron If Shakespeare “invented the human,” a claim made rather spectacularly by the critic Harold Bloom in a 1998 book, then the six British poets who comprised what was to become known as the Romantic Period perfected the mode. Shakespeare, in Bloom’s terms, depicted interiority in a unique way, allowing his characters to “overhear” themselves, to be self-reflective and existential (or proto-existential). Existentialism proper, along with the whole modern conception of self, has been merely catching up. It is my contention that the Romantics accelerated this paradigm shift by making the figure of The Poet highly subjective in a way it had not been before. Byron is the archetype. The “Byronic Hero” inaugurated in “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,” and perfected in “Manfred” and “Don Juan,” is subjectivity (at least male subjectivity) personified, a titillating amalgam of ambition, weakness, androgyny, power, lust; mortality and immortality in locked combat like Jacob and the angel. Only Jacob is not an abstract, allegorical figure here. These characters are Byron, by his own admission “such a strange mélange of good and evil that it would be difficult to describe me” (qtd. -

Thesis Submitted for the Degree Of

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL School of Arts How do electronic musicians make their music? Creative practice through informal learning resources. being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of MA in Music by Research (25004) in the University of Hull by Wai Kuen Wan (BEng University of Leeds, BA Leeds Metropolitan University) June 2017 Contents Abstract iv Introduction 1 Context and literature review 7 1. Compositional approaches 16 1.1 Curation 17 1.1.1 Context of materials 17 1.1.2 Juxtaposition 19 1.1.3 Assemblage 20 1.1.4 Personal sound archive 22 1.2 Sound manipulation 24 1.2.1 Custom modular tools 25 1.2.2 Destruction and degradation 28 1.2.3 Manipulating recorded performance 30 1.3 Indeterminacy and serendipity 31 1.4 Specificity of objectives 34 2. Conditions for creativity 40 2.1 Motivation 41 2.1.1 Self-serving 42 2.1.2 Enthusiasm 44 2.1.3 Commercial success 46 2.1.4 Reactionary responses 50 2.2 Personal growth 53 2.2.1 Exploratory learning 53 2.2.2 Early experiences 56 2.3 Discography for reflection 59 ii 2.4 Duration and nature of composition 61 2.4.1 Intensive work practice 62 2.4.2 Promoting objectivity 65 2.4.3 Learning vs making 66 3. Technological mediation 70 3.1 Attitudes to technology 70 3.1.1 Homogenisation of technologies 71 3.1.2 New ideas do not require new technologies 74 3.1.3 Obsessing and collecting 76 3.2 Tools for realisation 80 3.2.1 Proficiency and fluency with instruments 83 3.2.2 Opacity and affordance - enslaved to the (quantised) rhythm 86 3.3 Redefining technology 89 3.3.1 Subversion – extending the lexicon 90 3.3.2 Active Limitation 94 3.4 Instruments and their influence 97 3.4.1 Resisting conformity 98 3.4.2. -

Brian Eno's '77 Million Paintings' Is an Artwork That Won't Sit Still

Brian Eno's '77 Million Paintings' is an artwork that won't sit still http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/06/27/... Print This Article Back to Article Brian Eno's '77 Million Paintings' is an artwork that won't sit still Sylvie Simmons, Special to The Chronicle Wednesday, June 27, 2007 "Ah, synesthesia," Brian Eno says by telephone from England. "Vladimir Nabokov had a very severe and interesting form of that -- between characters of the Russian Cyrillic alphabet and color and taste sensations. One particular letter he described as being unquestionably a deep ginger in color with a dark, oily taste. I don't have anything like that." Perhaps not. But Eno admits there are times when he'll listen to one of his self-generating musical compositions and think, "It needs something cold blue over there or it needs something big, soft and brown." His instrumental music -- as fans of his "Ambient" and "Soundtrack" albums will attest -- paints pictures, and his visual art is musical: slow, rhythmic, ambient. When Brian Peter George St. John le Baptiste de la Salle Eno left Roxy Music in 1973, he re-emerged as the founding father of ambient music, embarking on a career in which mainstream projects -- like producing U2 -- were outnumbered by experimental, often computer-based ones as likely to reflect his art school training as his time as a rock keyboard player. This week Eno, 59, presents the U.S. premiere of his "77 Million Paintings," a three-night stand at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts Forum. -

Sydney Opera House Annual Report 2008-2009

The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Sir, we have the pleasure of presenting the Annual Report of the Sydney Opera House for the year ended Sydney Opera House 30 June 2009, for presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions 2008/09 Annual Report of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983. Kim Williams AM Richard Evans Chairman Chief Executive Sydney Opera House 2008/09 Annual Report Letter to Minister above Financials 36 Chairman’s Message 4 Financial Statements 38 CEO’s Message 6 Government Reporting 54 Vision & Goals 8 Performance List 66 Key Dates 8 ‘59 Who We Are 9 Our Focus 9 Key Outcomes 2008/09 & Objectives 2009/10 11 Performing Arts 12 Annual Giving 70 Music 14 Contact Information 73 Theatre 16 Opera 18 Index 74 Dance 20 Sponsors inside back cover Danish architect Jørn Utzon Work begins. Young Audiences 22 is announced as the winner of the international design competition by the Hon. JJ (Joe) Cahill. ‘57 Broadening the Experience 24 Building & Environment 26 Corporate Governance 28 The Trust 30 The Executive Team 32 People & Culture 34 sydneyoperahouse.com Where imagination takes you. Cover photography by David Min & Mel Koutchavlis The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Sir, we have the pleasure of presenting the Annual Report of the Sydney Opera House for the year ended Sydney Opera House 30 June 2009, for presentation to Parliament. This report has been prepared in accordance with the provisions 2008/09 Annual Report of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983.