The Cyber-Guitar System: a Study in Technologically Enabled Performance Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEW RELEASE Cds 24/5/19

NEW RELEASE CDs 24/5/19 BLACK MOUNTAIN Destroyer [Jagjaguwar] £9.99 CATE LE BON Reward [Mexican Summer] £9.99 EARTH Full Upon Her Burning Lips £10.99 FLYING LOTUS Flamagra [Warp] £9.99 HAYDEN THORPE (ex-Wild Beasts) Diviner [Domino] £9.99 HONEYBLOOD In Plain Sight [Marathon] £9.99 MAVIS STAPLES We Get By [ANTI-] £10.99 PRIMAL SCREAM Maximum Rock 'N' Roll: The Singles [2CD] £12.99 SEBADOH Act Surprised £10.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Cooking Vinyl] £9.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Deluxe 2CD w/ Alternative Mixes on Cooking Vinyl] £12.99 AKA TRIO (Feat. Seckou Keita!) Joy £9.99 AMYL & THE SNIFFERS Amyl & The Sniffers [Rough Trade] £9.99 ANDREYA TRIANA Life In Colour £9.99 DADDY LONG LEGS Lowdown Ways [Yep Roc] £9.99 FIRE! ORCHESTRA Arrival £11.99 FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE Veleno [Ltd. CD + Blu-Ray on Nuclear Blast] £14.99 FU MANCHU Godzilla's / Eatin' Dust +4 £11.99 GIA MARGARET There's Always Glimmer £9.99 JOAN AS POLICE WOMAN Joanthology [3CD on PIAS] £11.99 JUSTIN TOWNES EARLE The Saint Of Lost Causes [New West] £9.99 LEE MOSES How Much Longer Must I Wait? Singles & Rarities 1965-1972 [Future Days] £14.99 MALCOLM MIDDLETON (ex-Arab Strap) Bananas [Triassic Tusk] £9.99 PETROL GIRLS Cut & Stitch [Hassle] £9.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Deluxe CD w/ Bonus Tracks + More on Mascot]£14.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Mascot] £11.99 THE DAMNED THINGS High Crimes [Nuclear Blast] FEAT MEMBERS OF ANTHRAX, FALL OUT BOY, ALKALINE TRIO & EVERY TIME I DIE! £10.99 THE GET UP KIDS Problems [Big Scary Monsters] £9.99 THE MYSTERY LIGHTS Too Much Tension! [Wick] £10.99 COMPILATIONS VARIOUS ARTISTS Lux And Ivys Good For Nothin' Tunes [2CD] £11.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Max's Skansas City £9.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Par Les Damné.E.S De La Terre (By The Wretched Of The Earth) £13.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The Hip Walk - Jazz Undercurrents In 60s New York [BGP] £10.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The World Needs Changing: Street Funk.. -

Sonification As a Means to Generative Music Ian Baxter

Sonification as a means to generative music By: Ian Baxter A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts & Humanities Department of Music January 2020 Abstract This thesis examines the use of sonification (the transformation of non-musical data into sound) as a means of creating generative music (algorithmic music which is evolving in real time and is of potentially infinite length). It consists of a portfolio of ten works where the possibilities of sonification as a strategy for creating generative works is examined. As well as exploring the viability of sonification as a compositional strategy toward infinite work, each work in the portfolio aims to explore the notion of how artistic coherency between data and resulting sound is achieved – rejecting the notion that sonification for artistic means leads to the arbitrary linking of data and sound. In the accompanying written commentary the definitions of sonification and generative music are considered, as both are somewhat contested terms requiring operationalisation to correctly contextualise my own work. Having arrived at these definitions each work in the portfolio is documented. For each work, the genesis of the work is considered, the technical composition and operation of the piece (a series of tutorial videos showing each work in operation supplements this section) and finally its position in the portfolio as a whole and relation to the research question is evaluated. The body of work is considered as a whole in relation to the notion of artistic coherency. This is separated into two main themes: the relationship between the underlying nature of the data and the compositional scheme and the coherency between the data and the soundworld generated by each piece. -

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: an Analysis Into Graphic Design's

Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres by Vivian Le A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems (Honors Scholar) Presented May 29, 2020 Commencement June 2020 AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Vivian Le for the degree of Honors Baccalaureate of Science in Accounting and Business Information Systems presented on May 29, 2020. Title: Visual Metaphors on Album Covers: An Analysis into Graphic Design’s Effectiveness at Conveying Music Genres. Abstract approved:_____________________________________________________ Ryann Reynolds-McIlnay The rise of digital streaming has largely impacted the way the average listener consumes music. Consequentially, while the role of album art has evolved to meet the changes in music technology, it is hard to measure the effect of digital streaming on modern album art. This research seeks to determine whether or not graphic design still plays a role in marketing information about the music, such as its genre, to the consumer. It does so through two studies: 1. A computer visual analysis that measures color dominance of an image, and 2. A mixed-design lab experiment with volunteer participants who attempt to assess the genre of a given album. Findings from the first study show that color scheme models created from album samples cannot be used to predict the genre of an album. Further findings from the second theory show that consumers pay a significant amount of attention to album covers, enough to be able to correctly assess the genre of an album most of the time. -

User's Manual

USER’S MANUAL G-Force GUITAR EFFECTS PROCESSOR IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS The lightning flash with an arrowhead symbol The exclamation point within an equilateral triangle within an equilateral triangle, is intended to alert is intended to alert the user to the presence of the user to the presence of uninsulated "dan- important operating and maintenance (servicing) gerous voltage" within the product's enclosure that may instructions in the literature accompanying the product. be of sufficient magnitude to constitute a risk of electric shock to persons. 1 Read these instructions. Warning! 2 Keep these instructions. • To reduce the risk of fire or electrical shock, do not 3 Heed all warnings. expose this equipment to dripping or splashing and 4 Follow all instructions. ensure that no objects filled with liquids, such as vases, 5 Do not use this apparatus near water. are placed on the equipment. 6 Clean only with dry cloth. • This apparatus must be earthed. 7 Do not block any ventilation openings. Install in • Use a three wire grounding type line cord like the one accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. supplied with the product. 8 Do not install near any heat sources such • Be advised that different operating voltages require the as radiators, heat registers, stoves, or other use of different types of line cord and attachment plugs. apparatus (including amplifiers) that produce heat. • Check the voltage in your area and use the 9 Do not defeat the safety purpose of the polarized correct type. See table below: or grounding-type plug. A polarized plug has two blades with one wider than the other. -

Alleged KA Sexual Assault Goes Unprosecuted

ln Section 2 In Sports An Associated Collegiate Press Sick kids Do Hens Four-Star All-American Newspaper make the get a medicinal grade? - page BlO education page B 1 I Non-profit Org. FREE U.S. Postage Pa1d FRIDAY Newark, DE Volume 122, Number 40 250 Student Center, University of Delaware, Newark, DE 19716 Permit No. 26 March 8, 1996 Alleged KA sexual assault goes unprosecuted conviction is wrong." are taken to the attorney general's before reporting an assault. such as the one previously alleged, Delay in reporting the incident cited as Speaking hypothetically , office to decide if there is enough "What does it tell men?" she we do believe that the attorney reason for dismissal; Sigma Kappa says Pederson said, if there is a evidence to prosecute, whereas the asked, her face flushed. "Nothing. If general's decision is a fair one, significant gap between the rape and university's judicial system is I were a guy, I would fear nothing.'' clearly made after carefully decision tells men to 'fear nothing' its reporting, you not only lose the designed to deal with non-criminal Interfraternity Council President investigating the matter in full." physical evidence, but it gives those code of conduct violations on Bill Werde disagreed , saying the When asked to respond to the BY KIM WALKER said. involved a chance to corroborate r------- campus. case conveys the opposite message. charge that Sigma Kappa was Managing Nt:ws Editor ··we did not find enough their stories. Dana Gereghty, "The message [the decision] sent punished while the former fraternity evidence that could lead to a The former Kappa Alpha Order Dean of Students Timothy F. -

Dnafx Git Multi Effects Unit User Manual

DNAfx GiT multi effects unit user manual Musikhaus Thomann Thomann GmbH Hans-Thomann-Straße 1 96138 Burgebrach Germany Telephone: +49 (0) 9546 9223-0 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.thomann.de 27.11.2019, ID: 478040 Table of contents Table of contents 1 General information................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Further information........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Notational conventions.................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Symbols and signal words............................................................................................................... 8 2 Safety instructions.................................................................................................................................. 10 3 Features....................................................................................................................................................... 14 4 Installation.................................................................................................................................................. 15 5 Connections and operating elements........................................................................................... 25 6 Operating................................................................................................................................................... -

Negotiating Sound, Noise and Silence Through Improvisation, Composition and Image

University of Huddersfield Repository Harvey, Stephen Negotiating sound, noise and silence through improvisation, composition and image Original Citation Harvey, Stephen (2014) Negotiating sound, noise and silence through improvisation, composition and image. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/23395/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Negotiating sound, noise and silence through improvisation, composition and image Stephen Harvey A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MA by research August 2014 Copyright Statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

Computer Mediated Music Production: a Study of Abstraction and Activity

Computer mediated music production: A study of abstraction and activity by Matthew Duignan A thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science. Victoria University of Wellington 2008 Abstract Human Computer Interaction research has a unique challenge in under- standing the activity systems of creative professionals, and designing the user-interfaces to support their work. In these activities, the user is involved in the process of building and editing complex digital artefacts through a process of continued refinement, as is seen in computer aided architecture, design, animation, movie-making, 3D modelling, interactive media (such as shockwave-flash), as well as audio and music production. This thesis exam- ines the ways in which abstraction mechanisms present in music production systems interplay with producers’ activity through a collective case study of seventeen professional producers. From the basis of detailed observations and interviews we examine common abstractions provided by the ubiqui- tous multitrack-mixing metaphor and present design implications for future systems. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisors Robert Biddle and James Noble for their endless hours of guidance and feedback during this process, and most of all for allowing me to choose such a fun project. Michael Norris and Lissa Meridan from the Victoria University music department were also invaluable for their comments and expertise. I would also like to thank Alan Blackwell for taking the time to discuss my work and provide valuable advice. I am indebted to all of my participants for the great deal of time they selflessly offered, and the deep insights they shared into their professional world. -

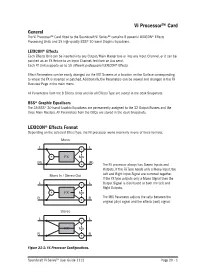

Vi Processor™ Card

Vi Processor™ Card General The Vi Processor™ Card fitted to the Soundcraft Vi Series™ contains 8 powerful LEXICON® Effects Processing Units and 35 high-quality BSS® 30-band Graphic Equalisers. LEXICON® Effects Each Effects Unit can be inserted into any Output/Main Master bus or into any Input Channel, or it can be patched as an FX Return to an Input Channel, fed from an Aux send. Each FX Unit supports up to 30 different professional LEXICON® Effects. Effect Parameters can be easily changed via the VST Screens at a location on the Surface corresponding to where the FX is inserted or patched. Additionally, the Parameters can be viewed and changed in the FX Overview Page in the main menu. All Parameters from the 8 Effects Units and for all Effects Type are stored in the desk Snapshots. BSS® Graphic Equalisers The 35 BSS® 30-band Graphic Equalizers are permanently assigned to the 32 Output Busses and the three Main Masters. All Parameters from the GEQs are stored in the desk Snapshots. LEXICON® Effects Format Depending on the selected Effect Type, the FX processor works internally in one of three formats: The FX processor always has Stereo Inputs and Outputs. If the FX Type needs only a Mono Input, the Left and Right Input Signal are summed together. If the FX Type outputs only a Mono Signal then the Output Signal is distributed to both the Left and Right Outputs. The MIX Parameter adjusts the ratio between the original (dry) signal and the effects (wet) signal. Figure 21-1: FX Processor Configurations. -

SRX PIANO II Software Synthesizer Owner's Manual

SRX PIANO II Software Synthesizer Owner’s Manual © 2020 Roland Corporation 01 Introduction For details on the settings for the DAW software that you’re using, refer to the DAW’s help or manuals. About Trademarks • VST is a trademark and software of Steinberg Media Technologies GmbH. • Roland is a registered trademark or trademark of Roland Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. • Company names and product names appearing in this document are registered trademarks or trademarks of their respective owners. 2 Contents Introduction . 2 EFFECTS Parameters . 34 Applying Effects . 34 Screen Structure . 4 Effect Settings . 34 Using SRX PIANO II . 5 Signal Flow and Parameters (ROUTING). 34 How to Edit Values . 5 Multi-Effect Settings (MFX) . 35 Initializing a value. 5 Chorus and Reverb Settings. 36 About the KEYBOARD button. 5 Effects List . 37 Overview of the SRX PIANO II . 6 Multi-Effects Parameters (MFX) . 37 How the SRX PIANO II is Organized. 6 About RATE and DELAY TIME . 38 How a Patch is Structured . 6 When Using 3D Effects . 38 How a Rhythm Set is Structured . 6 About the STEP RESET function . 38 Calculating the Number of Voices Being Used . 6 Chorus Parameters . 69 About the Effects . 7 Reverb Parameters . 69 Memory and Bank . 8 What is a Memory?. 8 Bank . 8 Changing to Other Bank. 8 Exporting the Bank . 8 Importing a Bank . 8 Creating/Deleting a Bank . 8 Renaming a Bank . 8 Category. 9 Memory . 9 Loading a Memory. 9 Saving the Memory . 9 Renaming the Memory. 9 Changing the Order of the Memories . -

Dnafx Git Multi Effects Unit User Manual

DNAfx GiT multi effects unit user manual Musikhaus Thomann Thomann GmbH Hans-Thomann-Straße 1 96138 Burgebrach Germany Telephone: +49 (0) 9546 9223-0 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.thomann.de 10.06.2021, ID: 478040 Table of contents Table of contents 1 General information................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Further information........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Notational conventions.................................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Symbols and signal words............................................................................................................... 8 2 Safety instructions.................................................................................................................................. 10 3 Features....................................................................................................................................................... 12 4 Installation.................................................................................................................................................. 13 5 Connections and operating elements........................................................................................... 23 6 Operating................................................................................................................................................... -

Music for the Augmented Pipe Organ

Music for the Augmented Pipe Organ by George Rahi B.A. (Hons.), University of British Columbia, 2011 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in the School for the Contemporary Arts Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © George Rahi 2019 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2019 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: George Rahi Degree: Master of Fine Arts Title: Music for the Augmented Pipe Organ Examining Committee: Chair: Peter Dickinson Professor Sabrina Schroeder Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor Arne Eigenfeldt Supervisor Professor Giorgio Magnanensi External Examiner Artist Date Defended/Approved: January 15, 2019 ii Abstract Music for the Augmented Pipe Organ is a composition for a 74-rank Casavant pipe organ which incorporates newly devised digital controls systems. The work stemmed from research into the confluences between the pipe organ and contemporary electronic and digital music practices. With a reflexive attention to the organ‟s spatial context and unique embodiment of the harmonic series, the work explores new sonic terrains that emerge through a digital approach to the world‟s oldest mechanical synthesizer. Through this process of hybridizing acoustic and digital sonic imaginations, the work creates a dialog between the vibrant material and ethereal space of the organ and the techniques of electronic and post-digital music forms. Site-specific elements such as the church‟s architecture and interior acoustics are further incorporated into the work through the use of a controlled feedback system and projection mapping, considering the resonant relationships between the instrument and its surrounding space as a generative element interwoven into the composition.