Everyday Experts: How People's Knowledge Can Transform the Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Formation and the Emergence of the Inca

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Assembling States: Community Formation And The meE rgence Of The ncI a Empire Thomas John Hardy University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hardy, Thomas John, "Assembling States: Community Formation And The meE rgence Of The ncaI Empire" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3245. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3245 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3245 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Assembling States: Community Formation And The meE rgence Of The Inca Empire Abstract This dissertation investigates the processes through which the Inca state emerged in the south-central Andes, ca. 1400 CE in Cusco, Peru, an area that was to become the political center of the largest indigenous empire in the Western hemisphere. Many approaches to this topic over the past several decades have framed state formation in a social evolutionary framework, a perspective that has come under increasing critique in recent years. I argue that theoretical attempts to overcome these problems have been ultimately confounded, and in order to resolve these contradictions, an ontological shift is needed. I adopt a relational perspective towards approaching the emergence of the Inca state – in particular, that of assemblage theory. Treating states and other complex social entities as assemblages means understanding them as open-ended and historically individuated phenomena, emerging from centuries or millennia of sociopolitical, cultural, and material engagements with the human and non-human world, and constituted over the longue durée. -

Peace Corps Listing for the Pclive Knowledge Sharing Platform (Digital Knowledge Hub) Showing the Resources Available at Pclive, 2017

Description of document: Peace Corps listing for the PCLive knowledge sharing platform (digital knowledge hub) showing the resources available at PCLive, 2017 Requested date: July 2017 Release date: 21-December-2017 Posted date: 07-January-2019 Source of document: Freedom of Information Act Request FOIA Officer U.S. Peace Corps 1111 20th Street, NW Washington D.C. 20526 The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. Since 1961. December 21, 2017 RE: FOIA Request No. 17-0143 This is in response to your Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Specifically, "I request a copy of the table of contents, listing or index for the PCLive knowledge sharing platform ( digital knowledge hub), showing the 1200+ resources available at PCLive." Attached, you have a spreadsheet (1 sheet) listing PCLive resources. -

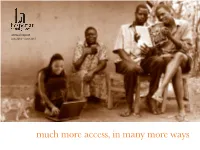

Much More Access, in Many More Ways Dear Friends, Later We Coordinated Their Getting Low-Cost Tablets It’S Been a Busy Year for Hesperian

annual report July 2014 – June 2015 1 much more access, in many more ways Dear friends, Later we coordinated their getting low-cost tablets It’s been a busy year for Hesperian. We released two loaded with the Spanish version of Safe Pregnancy and major new books in English—Health Actions for Women Birth. They learned to navigate the app, gave the trainers and Workers’ Guide to Health and Safety—produced feedback, then took the tablets home to use in their daily and published two new French editions, and helped work. These efforts resulted in a vast improvement in the partners complete translations into Bengali and Dari. reproductive health of Oaxacan communities, especially Hesperian Health Guides are now available in 84 in remote locations. languages—263 titles in all. We’re proud of how easy we’ve made it for people At the same time, an astonishing 4.7 million people, to get good health information. But making that mostly using cell phones and coming from every corner easy isn’t easy—it takes hard work, and lots of it. We of the globe, found critical health information online in accomplished everything described in this annual our expanded HealthWiki. And that’s not counting the report with a lean, hard-working staff of twenty, our people who used our award-winning mobile app, Safe global partners and nearly 12,000 hours donated by Pregnancy and Birth. devoted volunteers. Traditional midwives in Mexico made use of all three One other component is necessary—you. Your pathways. For the last six years, a group of these parteras contribution to our work is crucial, because it makes have been attending an annual, four-day training in the everything else possible. -

Lonkos, Curakas and Zupais the Collapse and Re-Making of Tribal Society in Central Chile, 1536-1560

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 29 INSTITUTE OF LATIN AMERICAN STUDIES RESEARCH PAPERS Lonkos, Curakas and Zupais The Collapse and Re-Making of Tribal Society in Central Chile, 1536-1560 Leonardo Leon Lonkos, Curakas and Zupais The Collapse and Re-Making of Tribal Society in Central Chile, 1536-1560 Leonardo Leon Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square, London WC1H 9HA British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0 901145 78 5 ISSN 0957-7947 © Institute of Latin American Studies University of London, 1992 CONTENTS Introduction 1 The War of the Pukaraes 3 The Economic War 10 The Flight of the Warriors 13 The Demographic Collapse 17 The Policy of Abuse and Theft 20 The Re-Making of Tribal Society 25 The End of an Era 39 Appendices I Encomiendas of Central Chile 43 II Caciques and Indian Villages in Central Chile 44 Glossary 46 Notes 48 Leonardo Leon is Lecturer in Colonial History at the University of Valparaiso, Chile. He was Research Assistant and later Honorary Research Fellow at the Institute of Latin American Studies, from 1983 to 1991. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper is the result of research begun in Chile in 1973 and then continued in London and Seville while I was a Research Assistant at the Institute of Latin American Studies of the University of London. I am grateful to Professor John Lynch for his support, friendship and very useful suggestions. I am also grateful to Ruben Stehberg, who introduced me to the subject, Rafael Varon and Jorge Hidalgo for their comments to earlier drafts, and to Andrew Barnard, Patrick Towe (OBI) and Sister Helena Brennan for their help with the English translation and to Tony Bell and Alison Loader for their work in preparing the text. -

Where Women Have No Doctor a Health Guide for Women

Where Women Have No Doctor A health guide for women A. August Burns Ronnie Lovich Jane Maxwell Katharine Shapiro Editor: Sandy Niemann Assistant editor: Elena Metcalf health guides Berkeley, California, USA www.hesperian.org health guides Published by: Hesperian Health Guides 1919 Addison St., #304 Berkeley, California 94704 • USA [email protected] • www.hesperian.org Copyright © 1997, 2018 by Hesperian First edition: June 1997 Sixth updated printing: December 2018 ISBN: 978-0-942364-25-5 Hesperian encourages you to copy, reproduce, or adapt any or all parts of this book, including the illustrations, provided that you do this for non-commercial purposes, credit Hesperian, and follow the other requirements of Hesperian’s Open Copyright License (see www.hesperian.org/about/ open-copyright). For certain kinds of adaptation and distribution, we ask that you first obtain permission from Hesperian. Contact [email protected] to use any part of this book for commercial purposes; in quantities more than 100 print copies; in any digital format; or with an organizational budget more than US$1 million. We also ask that you contact Hesperian for permission before beginning any translation, to avoid duplication of efforts, and for suggestions about adapting the information in this book. Please send Hesperian a copy of any materials in which text or illustrations from this book have been used. THIS REVISED EDITION CAN BE IMPROVED WITH YOUR HELP. If you are a community health worker, doctor, mother, or anyone with ideas or suggestions for ways this book could be changed to better meet the needs of your community, please write to Hesperian at the above address. -

Autonomía Indígena

AUTONOMÍA INDÍGENA FRENTE AL ESTADO NACIÓN Y A LA GLOBALIZACIÓN NEOLIBERAL AUTONOMÍA INDÍGENA FRENTE AL ESTADO NACIÓN Y A LA GLOBALIZACIÓN NEOLIBERAL Ileana Almeida Nidia Arrobo Rodas Lautaro Ojeda Segovia 2005 Autonomía Indígena frente al Estado nación y a la globalización neoliberal Ileana Almeida Nidia Arrobo Rodas Lautaro Ojeda Segovia Proyecto Latautonomy – Capítulo Ecuador Auspiciado por la Unión Europea Contraparte Nacional Fundación Pueblo Indio del Ecuador 1ra. Edición: Ediciones ABYA-YALA 12 de Octubre 14-30 y Wilson Casilla: 17-12-719 Teléfono: 2506-247/ 2506-251 Fax: (593-2) 2506-267 E-mail: [email protected] Sitio Web: www.abyayala.org Quito-Ecuador Impresión: Docutech Quito - Ecuador Foto de portada: Rolf Bloomberg Foto de contraportada: Joan Guerrero ISBN: 9978-22-490-4 Impreso en Quito-Ecuador, 2005. Nuestro agradecimiento a los espacios autonómicos que nos brindaron su apoyo y colaboración: Conaie, Ecuarunari, Pueblo de Sara Yaku, Dineib, Codenpe- Prodepine, Dnspi, Comisión de Asuntos Indígenas del Congreso Nacional, Municipios de Cotacachi, Guamote y Otavalo y comunidades indígenas de Cotopaxi, Chimborazo e Imbabura. ÍNDICE ANTECEDENTES .......................................................................................... 11 PRIMERA PARTE Multiplicar los espacios de la Autonomía Indígena ..................................... 15 INTRODUCCIÓN ......................................................................................... 17 El proceso organizativo de los pueblos indígenas del Ecuador .................. -

Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1952 Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times John L. Sorenson Sr. Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Sorenson, John L. Sr., "Evidences of Culture Contacts Between Polynesia and the Americas in Precolumbian Times" (1952). Theses and Dissertations. 5131. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5131 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. e13 ci j rc171 EVIDENCES OPOFCULTURE CONTACTS BETWEEN POLIIESIAPOLYNESIA AND tiletlleTIIETHE AMERICAS IN preccluivibianPREC olto4bian TIMES A thesthesisis presented tobo the department of archaeology brbrighamighambigham Yyoungoung universityunivervens 1 ty provo utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts n v rb hajbaj&aj by john leon sorenson july 1921952 ACmtodledgiventsackiiowledgments thanks are proffered to dr M wells jakenjakemjakemanan and dr sidney B sperry for helpful corencoxencommentsts and suggestions which aided research for this thesis to the authors wife kathryn richards sorenson goes gratitude for patient forbearance constant encouragement -

Speakers' Bios

Press Past Review Home Hotel Program Contact Us Room Events Committee Speaker Biographies Keynote Speaker: Vinton G. Cerf Vice President and Chief Internet Evangelist, Google Vinton G. Cerf is the Vice President and Chief Internet Evangelist at Google. Cerf has served as vice president and chief Internet evangelist for Google since October 2005. In this role, he is responsible for identifying new enabling technologies to support the development of advanced, Internet-based products and services from Google. He is also an active public face for Google in the Internet world. Cerf is widely known as one of the "Fathers of the Internet," Cerf is the co-designer of the TCP/IP protocols and the architecture of the Internet. In December 1997, President Clinton presented the U.S. National Medal of Technology to Cerf and his colleague, Robert E. Kahn, for founding and developing the Internet. Kahn and Cerf were named the recipients of the ACM Alan M. Turing award in 2004 for their work on the Internet protocols. The Turing award is sometimes called the "Nobel Prize of Computer Science." In November 2005, President George Bush awarded Cerf and Kahn the Presidential Medal of Freedom for their work. The medal is the highest civilian award given by the United States to its citizens. In April 2008, Cerf and Kahn received the prestigious Japan Prize. For a more detailed bio please click here. Speakers: Mr. Adil Allawi Director, Diwan Software Adil Allawi has been working on Arabic computing and multilingual software since 1982 and as such takes personal responsibility for all the problems that bi-di algorithms have caused to the Arabic language. -

Redalyc.ARCHITECTURE and EMPIRE at LATE PREHISPANIC TARAPACÁ VIEJO, NORTHERN CHILE

Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena ISSN: 0716-1182 [email protected] Universidad de Tarapacá Chile Zori, Colleen; Urbina A., Simón ARCHITECTURE AND EMPIRE AT LATE PREHISPANIC TARAPACÁ VIEJO, NORTHERN CHILE Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena, vol. 46, núm. 2, 2014, pp. 211-232 Universidad de Tarapacá Arica, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32631014004 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Volumen 46, Nº 2, 2014. Páginas 211-232 Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena ARCHITECTURE AND EMPIRE AT LATE PREHISPANIC TARAPACÁ VIEJO, NORTHERN CHILE ARQUITECTURA E IMPERIO EN TARAPACÁ VIEJO, UN SITIO PREHISPÁNICO TARDÍO EN EL NORTE DE CHILE Colleen Zori1 and Simón Urbina A.2,3 Imperial conquest and subsequent strategies of integration can be detected in changes to regional infrastructure, such as road systems and the architectural layout and construction techniques of provincial settlements. Located in the Tarapacá Valley of northern Chile, the site of Tarapacá Viejo underwent significant architectural remodeling when the valley was incorporated into the Inka empire in the XV century AD. This article examines (1) how Tarapacá Viejo fit into the overall network of Inka or Inka-influenced sites in northern Chile; (2) how the construction techniques and architectural layout were transformed upon conquest of the valley by the Inka; and (3) what changes and continuities characterized the Early Colonial period (AD 1,532-1,700) occupation of the site. -

Other Titles from Hesperian Health Guides

Other Titles from Hesperian Health Guides: Where There Is No Doctor, by Disabled Village Children, David Werner, Carol Thuman by David Werner, covers and Jane Maxwell, is the most most common disabilities of widely used health manual in the children, giving suggestions for world with information on how rehabilitation and explaining how to diagnose, treat, and prevent to make a variety of low-cost aids. common diseases, emphasizing Emphasis is placed on how to prevention and the importance of community help children with disabilities find a role and be mobilization. 512 pages. accepted in the community. 672 pages. Workers’ Guide to Health and Helping Children Who Are Deaf, Safety, by Todd Jailer, Miriam by Darlena David, Devorah Lara-Meloy and Maggie Robbins, Greenstein and Sandy Niemann, makes occupational safety and aids parents, teachers, and other health accessible to those most caregivers to help deaf children affected by hazards — the workers learn basic communications skills themselves. An invaluable resource and language. Includes simple for training workers, supervisors, and safety methods to assess hearing, develop listening committees, and in courses on labor relations. skills, and explore community support for deaf children. 250 pages. Where There Is No Dentist, by Murray Dickson, shows how to care Helping Children Who Are Blind, for teeth and gums at home, and by Sandy Niemann and Namita in community and school settings. Jacob, aids parents and caregivers Detailed, illustrated information on of blind children from birth to age dental equipment, placing fillings 5 develop all their capabilities. and pulling teeth, teaching hygiene Topics include: assessing how and nutrition, and HIV and oral health. -

Pdf 2 Healthcare Information for All

Analysis Universal access to essential health BMJ Glob Health: first published as 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002475 on 17 May 2020. Downloaded from information: accelerating progress towards universal health coverage and other SDG health targets 1 2 3 Geoff Royston , Neil Pakenham- Walsh, Chris Zielinski To cite: Royston G, ABSTRACT Summary box Pakenham- Walsh N, The information that people need to protect and manage Zielinski C. Universal access to their own health and the health of those for whom ► Effective people- centred healthcare requires the essential health information: they are responsible is a fundamental element of an accelerating progress towards public, carers and frontline health workers to have effective people- centred healthcare system. Achieving universal health coverage timely access to reliable, practical, health informa- universal health coverage (UHC) requires universal and other SDG health tion (we term this essential health information), yet access to essential health information. While it was targets. BMJ Global Health in many parts of the world this is often difficult for recently recognised by the World Medical Association, 2020;5:e002475. doi:10.1136/ people to obtain. bmjgh-2020-002475 universal access to essential health information is not yet ► Universal access to essential health information is reflected in official monitoring of progress on UHC for the therefore a prerequisite for, and indeed a key com- sustainable development goals (SDGs). In this paper, we Handling editor Seye Abimbola ponent of, universal health coverage (UHC), yet this outline key features that characterise universal access fundamental role for UHC of access to essential Received 12 March 2020 to essential health information and indicate how it is health information appears to have been largely Revised 22 April 2020 increasingly achievable. -

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto De Filosofia E Ciências Humanas ALEJANDRO RAMÍREZ JAIMES. “ENFERMEDAD OCCIDENTAL

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas ALEJANDRO RAMÍREZ JAIMES. “ENFERMEDAD OCCIDENTAL SE CURA CON MEDICINA OCCIDENTAL”: AUTONOMÍA INDÍGENA, TERRITORIALIDADES Y LA CREACIÓN DEL PARQUE NACIONAL NATURAL YAIGOJÉ APAPORIS EN LA AMAZONIA COLOMBIANA. “DOENÇA OCIDENTAL É CURADA PELA MEDICINA OCIDENTAL”: AUTONOMÍA INDÍGENA, TERRITORIALIDADES E A CRIAÇÃO DO PARQUE NACIONAL NATURAL YAIGOJE APAPORIS NA AMAZÔNIA COLÔMBIANA. CAMPINAS 2018 ALEJANDRO RAMÍREZ JAIMES “ENFERMEDAD OCCIDENTAL SE CURA CON MEDICINA OCCIDENTAL”: AUTONOMÍA INDÍGENA, TERRITORIALIDADES Y LA CREACIÓN DEL PARQUE NACIONAL NATURAL YAIGOJÉ APAPORIS EN LA AMAZONIA COLOMBIANA. “DOENÇA OCIDENTAL É CURADA PELA MEDICINA OCIDENTAL”: AUTONOMÍA INDÍGENA, TERRITORIALIDADES E A CRIAÇÃO DO PARQUE NACIONAL NATURAL YAIGOJE APAPORIS NA AMAZÔNIA COLÔMBIANA. Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em antropologia Social. e Disertación presentada al Instituto de Filosofía y Ciencias Humanas de la Universidad Estadual de Campinas como parte de los requisitos exigidos para la obtención del título de Maestría en Antropología Social. Orientadora: EMILIA PIETRAFESA DE GODOI. ESTE EXEMPLAR CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA DISSERTAÇÃO DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO ALEJANDRO RAMIREZ JAIMES, E ORIENTADA PELA DRA. EMÍLIA PIETRAFESA DE GODOI. CAMPINAS 2018 UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas A Comissão Julgadora dos trabalhos de Defesa de Mestrado, composta pelos Professores Doutores a seguir descritos, em sessão pública realizada em 23 de agosto de 2018, considerou o candidato Alejandro Ramírez Jaimes aprovado. Professora Emília Pietrafesa de Godoi (Orientadora) Professor Luis Abraham Cayón Durán (membro externo) Professor Antonio Roberto Guerreiro Junior (membro interno) A Ata de Defesa, assinada pelos membros da Comissão Examinadora, consta no processo de vida acadêmica do aluno.