Transit Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smart Location Database Technical Documentation and User Guide

SMART LOCATION DATABASE TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION AND USER GUIDE Version 3.0 Updated: June 2021 Authors: Jim Chapman, MSCE, Managing Principal, Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. (UD4H) Eric H. Fox, MScP, Senior Planner, UD4H William Bachman, Ph.D., Senior Analyst, UD4H Lawrence D. Frank, Ph.D., President, UD4H John Thomas, Ph.D., U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization Alexis Rourk Reyes, MSCRP, U.S. EPA Office of Community Revitalization About This Report The Smart Location Database is a publicly available data product and service provided by the U.S. EPA Smart Growth Program. This version 3.0 documentation builds on, and updates where needed, the version 2.0 document.1 Urban Design 4 Health, Inc. updated this guide for the project called Updating the EPA GSA Smart Location Database. Acknowledgements Urban Design 4 Health was contracted by the U.S. EPA with support from the General Services Administration’s Center for Urban Development to update the Smart Location Database and this User Guide. As the Project Manager for this study, Jim Chapman supervised the data development and authored this updated user guide. Mr. Eric Fox and Dr. William Bachman led all data acquisition, geoprocessing, and spatial analyses undertaken in the development of version 3.0 of the Smart Location Database and co- authored the user guide through substantive contributions to the methods and information provided. Dr. Larry Frank provided data development input and reviewed the report providing critical input and feedback. The authors would like to acknowledge the guidance, review, and support provided by: • Ruth Kroeger, U.S. General Services Administration • Frank Giblin, U.S. -

SEATTLE STREETCAR Operations Report

Seattle Department of Transportation SEATTLE STREETCAR Operations Report July 2019 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................4 1.1. South Lake Union Streetcar.....................................................................4 1.2. First Hill Streetcar ...................................................................................6 1.3. Center City Connector .............................................................................6 2. OPERATIONS HIGHLIGHTS ..................................................................................7 2.1. Governance Structure and Budget Overview ..........................................7 2.2. Status of Negotiations on New Streetcar ILA..........................................8 2.3. Safety & Security Update .........................................................................9 3. FINANCIAL METRICS .........................................................................................10 3.1. South Lake Union Streetcar...................................................................10 3.2. First Hill Streetcar .................................................................................13 3.3. Investment in Streetcar Operations ......................................................15 4. PERFORMANCE METRICS ..................................................................................17 4.1. Ridership ................................................................................................17 -

Examining the Development Effects of Modern-Era Streetcars: an Assessment of Portland and Seattle

Project 1798 October 2018 Examining the Development Effects of Modern-Era Streetcars: An Assessment of Portland and Seattle Jeffrey Brown, PhD Joel Mendez, PhD MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE transweb.sjsu.edu MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER LEAD UNIVERSITY OF Hon. Norman Y. Mineta Mineta Consortium for Transportation Mobility MTI BOARD OF TRUSTEES Founded in 1991, the Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI), an organized research and training unit in partnership with the Founder, Honorable Norman Richard Anderson (Ex-Officio) Steve Heminger* (TE 2018) Dan Smith (TE 2020) Lucas College and Graduate School of Business at San José State University (SJSU), increases mobility for all by improving the safety, Mineta (Ex-Officio) President and CEO Executive Director President Secretary (ret.), US Department of Amtrak Metropolitan Transportation Capstone Financial Group, Inc. efficiency, accessibility, and convenience of our nation’s transportation system. Through research, education, workforce development, Transportation Commission (MTC) and technology transfer, we help create a connected world. MTI leads the four-university Mineta Consortium for Transportation Vice Chair Laurie Berman (Ex-Officio) Paul Skoutelas (Ex-Officio) Hill & Knowlton, Inc. Director Diane Woodend Jones (TE 2019) President & CEO Mobility, a Tier 1 University Transportation Center funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant California Department Principal & Chair of Board American Public Transportation Secretary for Research and -

Arkansas River SERVICE

7 W. Broadway St. Argenta E. Broadway St. 26 10 10 13 District 4 4 City Services Dickey Stephens 36 36 Building Park Simmons Bank Poplar St. Arena NLR Chamber Main St. Maple St. of Commerce Washington Ave. 18 18 HOW TO RIDE Wyndham Riverfront NORTH Little Rock LITTLE ROCK It’s Easy: Riverfront D 13 r. E. Arkansas Dr. rrmetro 7 501.375.1163 rrmetro.org @rrmetro rrmetro Riverfront D 10 r. @rrmetro 4 36 rrmetro.org 18 USS Broadway Razorback Submarine 501-375-6717 Bridge Main Street Bridge 30 METRO Connect Arkansas Junction Bridge Riverdale Zone DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Little Rock (pedestrian/bicycle) River Little Rock Robinson Old State Marriott House PLAN YOUR TRIP Center Statehouse Clinton Presidential La Harpe Blvd. First Security …by entering your starting and ending Convention Little Rock Park Bridge Center Amphitheater (pedestrian/bicycle) destinations using the homepage trip City Regional Chamber planner at rrmetro.org. Hall Witt Stephens Jr. Determine Your Fare and Rock Region METRO Central Arkansas How You Will Pay Pass Sale Locations River Nature Center FIND RELATED ROUTE MAPS 13 Pulaski Co. Market Fare information may be found at rrmetro.org. RIVER CITIES TRAVEL CENTER 10 Central Arkansas District AND SCHEDULES Regional Markham St. 4 Library System …by downloading the free METROtrack Cash or passes are accepted on the bus. 310 E. Capitol Ave., Little Rock, Pulaski Co. 1 Center Courthouse 36 Main Branch Arkansas mobile app (it’s one word: METROtrack, when Cash, passes, debit or credit cards and major 7 a.m.-6 p.m. 7 Capital Museum of “tap and pay” services (Apple Pay, Google Hotel 18 President Clinton Ave. -

2018 SSO Workshop Introduction of Ssoas

2018 SSO Program Workshop Introduction of State Safety Oversight Agency Attendees Dr. Alfonz Ruth Office of Administration Federal Transit Administration May 15, 2018 ARIZONA Arizona Department of Transportation Valley Metro Valley Metro Rail Light Rail Streetcar* City of Tucson Sun Link Streetcar 2 ARKANSAS Arkansas State Highway and Transportation Department Rock Region Metro Metro Streetcar Streetcar 3 CALIFORNIA California Public Utilities Commission Bay Area Rapid Transit BART Heavy Rail Automated Guideway Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority Metro Rail Light Rail Heavy Rail North County Transit District SPRINTER Hybrid Rail Orange County Transportation Authority OC Streetcar Streetcar* Continued on Next Page 4 CALIFORNIA California Public Utilities Commission Continued…. Riverfront Authority Downtown Riverfront Streetcar Streetcar* Sacramento Regional Transit District Regional Transit Light Rail San Diego Metropolitan Transit System Trolley Light Rail 5 CALIFORNIA California Public Utilities Commission Continued…. San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Muni Metro Light Rail Cable Car Streetcar Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) Light Rail 6 COLORADO Colorado Public Utilities Commission Regional Transportation District RTD Rail Light Rail 7 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA D.C. Fire and Emergency Management Services D.C. Department of Transportation DC Streetcar Streetcar 8 DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA MARYLAND VIRGINIA Tri-State Oversight Committee Metrorail Safety Commission -

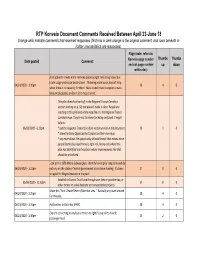

RTP Konveio Document Comments Received Between April 23-June 18

RTP Konveio Document Comments Received Between April 23-June 18 Orange cells indicate comments that received responses (first row in dark orange is the original comment, and rows beneath in lighter orange/italics are responses) Page (note: refers to Thumbs Thumbs Date posted Comment Konveio page number and not page number up down within doc) Add option to create more rail lines (subway/light rail) along heavy bus route usage and major destinations. Throwing more buses doesn't help 04/24/2020 - 1:20pm 26 4 0 when there is no capacity for them. Mass transit must transport a mass amount of people, or else it isn't mass transit. This plan does that (sort of) in the Regional Transit Corridors section starting on p. 58, but doesn't make it clear. People are reacting to this pink and white map like it is the Regional Transit Corridors map. They're not to blame for being confused. It might help to: 06/03/2020 - 6:12pm * put the Regional Transit Corridors section earlier in the document 26 1 0 * show the Early Opportunity Corridors on their own map * say more about the opportunity to build transit that moves more people faster (bus rapid transit, light rail, heavy rail) where this plan has identified are the places where improvements like that should be prioritized Look at the 1978 Metro Subway plan. Identify funding for long term and do 04/24/2020 - 1:22pm not rely on the state or federal government to continue funding. It's been 27 8 0 stripped for illogical reasons in the past! Establish a Transit Trust Fund through user fees or gasoline tax, or 05/06/2020 - 11:50pm 27 8 0 other means to solely dedicate to transportation projects. -

October 3, 2019 SUBJECT: Beltline Trail Interlocal Agreement with City of Omaha and Omaha Municipal Land Bank

MEMORANDUM TO: Programs, Projects, and Operations Subcommittee FROM: Eric Williams, Natural Resources Planner DATE: October 3, 2019 SUBJECT: Beltline Trail Interlocal Agreement with City of Omaha and Omaha Municipal Land Bank The purpose of this Interlocal Agreement is to specify the terms and conditions upon which the City of Omaha, Omaha Municipal Land Bank, and the NRD will collaborate to design, develop, construct, operate and maintain the Beltline Trail. This project is generally located from Hamilton Street at Military Ave, to 31st and Sprague Street. The corridor of the former railroad known as the “Omaha Beltline” has been vacant for multiple decades, and has been repeatedly identified in planning documents as a potential location for development of a combined recreation and active transportation corridor. The most comprehensive work on this concept was completed in 2012 by the nonprofit design group Emerging Terrain, but no action was taken on land acquisition or construction on any of the former railroad property. Creation of the Omaha Municipal Land Bank provided an organization with the specific purpose “to serve as a catalyst for transforming distressed properties into community assets.” Beginning in 2017, NRD staff met with the Land Bank and other organization to discuss what steps would be necessary to move forward with the concept of the trail corridor. A preliminary design document highlighted that strategic acquisition of properties from relatively few owners would allow for connection between many major community features; Walnut Hill Elementary School, City Sprouts (nonprofit community garden), Omaha Permaculture, King Elementary School, Adams Park, Malcolm X Memorial Foundation, North Omaha Transit Center. -

Arkansas Public Transportation

Arkansas Public Transportation 2019 D I R E C T O R Y Publicly and Privately Owned Transit Administered by the Arkansas Department of Transportation Table of Contents Introduction.................................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Transportation Resources Arkansas Department of Transportation (Department) Staff… ............................................................................................................ 2 Federal Transit Administration (FTA) Staff .............................................................................................................................................4 Arkansas Transit Association (ATA) Staff................................................................................................................................................5 Program Information .............................................................................................................................................................................6 Glossary ..................................................................................................................................................................................................8 Urbanized Public Transportation Systems (Section 5307) ........................................................................................................................... 10 Rural Public Transportation Systems -

2017 Annual Budget Report ROCK REGION METROPOLITAN TRANSIT AUTHORITY

2017 Annual Budget Report ROCK REGION METROPOLITAN TRANSIT AUTHORITY 2017 Annual Budget Report Jarod Varner Executive Director Prepared by: Department of Finance and Administration Wanda Crawford, Chief Financial Officer Justin Avery, Accounting Manager TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................. 1 FOREWORD ............................................................................................................................................... 3 ORGANIZATION OF BUDGET DOCUMENT................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW ......................................................................................7 METRO AT A GLANCE ................................................................................................................................ 8 DESCRIPTION OF SERVICES AND FLEET ..................................................................................................... 8 BOARD OF DIRECTORS ............................................................................................................................ 10 MOVE CENTRAL ARKANSAS STRATEGIC PLAN ........................................................................................ 11 MISSION, AGENCY GOALS, -

Long Range Transportation Plan 2035

2035 LONG-RANGE TRANSPORTATION PLAN METROPOLITAN AREA PLANNING AGENCY MAPA 2035 Long Range Transportation Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Summary ........................................................................................................................... Before 1 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Demographics and Forecasts ................................................................................................. 6 3. Regional Goals .............................................................................................................................. 23 4. Future Growth and Livability ..............................................................................................29 5. Street, Highway and Bridge .................................................................................................. 52 6. Traffic and Congestion Trends * ....................................................................................... 66 7. Future Streets and Highways ............................................................................................. 84 Federally-Eligible Project Map and Listing: ............................................... After 96 8. Transit ............................................................................................................................................... 97 9. Coordinated Transit and Paratransit ........................................................................... -

See the Twin Cities in Style on the METRO Streetcar Rent a METRO

FREE Fare METRO Streetcar rides are fare-free throughout 2019. Enjoy the ride! Streetcar Hours Blue Line Sunday: 11:40 a.m.- 6:45 p.m. Monday-Wednesday: 8:20 a.m.-10 p.m. Thursday-Saturday: 8:20 a.m.-12 a.m. Green Line Sunday: No Service Monday-Saturday: 9 a.m.-5 p.m. See the Twin Cities in Style on the METRO Streetcar There is no METRO Streetcar service New Year’s Day, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving Day and Christmas Day. Opened Nov. 1, 2004, the METRO Streetcar is a fun, unique way Occasionally, the METRO Streetcar schedule changes to accommodate to take in the downtown sights of central Arkansas’ “twin cities.” system maintenance, road closures and other events. Operating three historic replica streetcars along a 3.4-mile route, the Visit rrmetro.org for service alerts. METRO Streetcar system spans the Arkansas River and links some of the most vibrant destinations in Pulaski County, including the Clinton Check for Service Alerts BEFORE You Ride: Presidential Center and headquarters of the global nonprofit Heifer International; North Little Rock’s historic Argenta district; the Little Detours, inclement weather, electrical outages and Rock River Market and Creative Corridor; and favorite restaurants, electrical storms, and unusual traffic congestion may hotels, brewpubs, cultural attractions, shops and more. affect service. Check for active service alerts, which, when in effect, are always: Rent a METRO Streetcar • In a red bar at the top of rrmetro.org Take in Downtown Little Rock, the Arkansas River and North Little Rock’s Argenta District aboard a METRO Streetcar private In the METROtrack app Service Alerts • charter! Food, drinks and décor allowed. -

Omaha Metro Area Transit (Metro) DBE Program Compliance Review

Omaha Metro Area Transit (Metro) DBE Program Compliance Review FINAL REPORT March 2016 Federal Transit Administration This page intentionally left blank to facilitate duplex printing. DBE Program Compliance Review: Omaha Metro, March, 2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary ..........................................................................................................................9 1. General Information ..................................................................................................................12 2. Jurisdiction and Authorities .......................................................................................................13 3. Purpose and Objectives .............................................................................................................14 3.1 Purpose .......................................................................................................................... 14 3.2 Objectives ...................................................................................................................... 14 4. Background Information ............................................................................................................16 4.1 Introduction to Metro and Organizational Structure ................................................... 16 4.2 Budget and FTA-Assisted Projects ................................................................................ 16 4.3 DBE Program ................................................................................................................