Public Expenditure Review Improving the Poverty Focus of Public Spending

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talks Trash Commissioned Its Newest Packed the Fuselage with Leigh Burke-Class Destroy- Guided-Missile Destroy- Snow Using His Bare Hands Er That Bears His Name

MONDAY, DECEMBER 3, 2018 Swampscott City residents (again) exchange talks their ideas By Bella diGrazia trash ITEM STAFF By Bella diGrazia SWAMPSCOTT — The town’s rst ITEM STAFF idea exchange had the high school packed with residents eager to share LYNN — Five months their visions for Swampscott early after Lynn’s new trash Saturday morning. fees caught residents off No matter how big or small, town guard, confusion about of cials wanted their residents’ ideas the wording of the bills has the complaints piling heard. The daylong event had break- in. out groups, with two volunteer facili- Aggravated Lynners tators each, that focused on ideas for pleaded with their ward seniors; beauti cation, culture, and councilors and council- recreation; children; town services, - ors-at-large about a num- nances, and taxes; and the waterfront ber of problems regard- areas. ing the second round of “You know it’s a great turnout when trash fee bills that were someone comes up to you and com- sent out last week. An plains there was no parking,” said emergency meeting has Board of Selectmen Chair Peter Spell- been scheduled for Mon- ios. day with a number of the Some of the most echoed ideas in- city’s department heads cluded a recreational center where and James Lamanna, the kids can hang out; bringing back the city’s attorney. town’s “Welcome” sign; helping seniors “I envision a series of learn how to work a computer; bath- internal meetings to try rooms, showers, and concession stands to solve this,” Lamanna at the beaches; and nding ways to get said. -

Rage in Eden Records, Po Box 17, 78-210 Bialogard 2, Poland [email protected]

RAGE IN EDEN RECORDS, PO BOX 17, 78-210 BIALOGARD 2, POLAND [email protected], WWW.RAGEINEDEN.ORG Artist Title Label HAUSCHKA ROOM TO EXPAND 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX BLUE NOTEBOOKS, THE 130701/FAT CAT CD RICHTER, MAX SONGS FROM BEFORE 130701/FAT CAT CD ASCENSION OF THE WAT NUMINOSUM 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY COVER UP 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY LAST SUCKER, THE 13TH PLANET RECORDS LTD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE BLOOD 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD MINISTRY RIO GRANDE DUB YA 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD PRONG POWER OF THE DAMAGER 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKED AND LOADED 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD REVOLTING COCKS COCKTAIL MIXXX 13TH PLANET RECORDS CD BERNOCCHI, ERALDO/FE MANUAL 21ST RECORDS CD BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FA BOTTO & BRUNO/THE FAMILY 21ST RECORDS CD FLOWERS OF NOW INTUITIVE MUSIC LIVE IN COLOGNE 21ST RECORDS CD LOST SIGNAL EVISCERATE 23DB RECORDS CD SEVENDUST ALPHA 7 BROS RECORDS CD SEVENDUST CHAPTER VII: HOPE & SORROW 7 BROS RECORDS CD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM COLD A DIFFERENT DRUM MCD A BLUE OCEAN DREAM ON THE ROAD TO WISDOM A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE ALTERNATES AND REMIXES A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE EVENING BELL, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE FALLING STAR, THE A DIFFERENT DRUM CD B!MACHINE MACHINE BOX A DIFFERENT DRUM BOX BLUE OCTOBER ONE DAY SILVER, ONE DAY GOLD A DIFFERENT DRUM CD BLUE OCTOBER UK INCOMING 10th A DIFFERENT DRUM 2CD CAPSIZE A PERFECT WRECK A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMIC ALLY TWIN SUN A DIFFERENT DRUM CD COSMICITY ESCAPE POD FOR TWO A DIFFERENT DRUM CD DIGNITY -

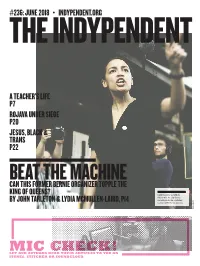

Issue 236 Jun 1, 2018 Download

The#236: JUne 2018 IndypendenT• IndypendenT.ORG A TeACheR’S LIFe p7 ROJAVA UndeR SIeGe p20 JeSUS, BLACK & TRAnS p22 CAnBeAT ThIS FORMeR The BeRnIe MAChIne ORGAnIZeR TOppLe The KInG OF QUeenS? Congressional candidate Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez By JOhn TARLeTOn & LydIA MCMULLen-LAIRd, p14 speaking outside a subway station in Elmhurst, Queens. ELIA GRAN MIC CHECK! LET OUR AUTHORS READ THEIR ARTICLES TO YOU ON ITUNES, STITCHER OR SOUNDCLOUD. 2 COMMUNITY CALENDAR The IndypendenT THE INDYPENDENT, INC. 388 Atlantic Avenue, 2nd Floor Brooklyn, NY 11217 212-904-1282 www.indypendent.org Twitter: @TheIndypendent facebook.com/TheIndypendent BOARD OF DIRECTORS: Ellen Davidson, Anna Gold, JUNE 1–JUNE 24 living in the blockaded Gaza Strip. SAT JUNE 16 WED JUNE 20 Alina Mogilyanskaya, Ann 8PM • FREE CASA LA FEMME 1PM–4PM • FREE 6PM–10PM • $20 Schneider, John Tarleton THEATER: OTHELLO 140 Charles St., Mnhtn PARADE: THE MERMAID PARADE PARTY: BIG GAY ROLLER SKATE: Set amid war and palace intrigue in A celebration of ancient mythol- PRIDE EDITION EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: the 17th-century Mediterranean, WED JUNE 6 ogy, the honky-tonk rituals of the Guest DJ, skate rental, cocktails, John Tarleton this classic drama about a noble 7PM–10PM • FREE seaside and community pride. rinkside dining, drag show. Show black Venetian general whose GATHERING/BOOK LAUNCH: CONEY ISLAND your rainbow colors. ASSOCIATE EDITOR: THE BATTLE FOR PARADISE (LA 1208 Surf Ave., Bklyn LEFRAK CENTER AT LAKESIDE Peter Rugh marriage is sabotaged by theater’s most infamous villain, Iago, re- BATALLA POR EL PARAÍSO) PROSPECT PARK CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: mains Shakespeare’s most urgent An urgent conversation about how SAT JUNE 16 171 Eastern Pkwy, Bklyn Ellen Davidson, Alina and relevant tragedy. -

TRANSCULTURAL SPACES in SUBCULTURE: an Examination of Multicultural Dynamics in the Japanese Visual Kei Movement

TRANSCULTURAL SPACES IN SUBCULTURE: An examination of multicultural dynamics in the Japanese visual kei movement Hayley Maxime Bhola 5615A031-9 January 10, 2017 A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies Waseda University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts TRANSCULTURAL SPACES IN SUBCULTURE 2 Abstract of the Dissertation The purpose of this dissertation was to examine Japanese visual kei subculture through the theoretical lens of transculturation. Visual kei (ヴィジュアル系) is a music based subculture that formed in the late 1980’s in Japan with bands like X Japan, COLOR and Glay. Bands are recognized by their flamboyant (often androgynous appearances) as well as their theatrical per- formances. Transculturation is a term originally coined by ethnographer Fernando Ortiz in re- sponse to the cultural exchange that took place during the era of colonization in Cuba. It de- scribes the process of cultural exchange in a way that implies mutual action and a more even dis- tribution of power and control over the process itself. This thesis looked at transculturation as it relates to visual kei in two main parts. The first was expositional: looking at visual kei and the musicians that fall under the genre as a product of transculturation between Japanese and non- Japanese culture. The second part was an effort to label visual kei as a transcultural space that is able to continue the process of transculturation by fostering cultural exchange and development among members within the subculture in Japan. Chapter 1 gave a brief overview of the thesis and explains the motivation behind conduct- ing the research. -

Karaoken Presenteras Av Sveriges J-Rock-Förening

Karaoken presenteras av Sveriges J-rock-förening Karaokelista – Innehåll s. 3 Animé & Live Action s. 20 J-rock s. 26 J-pop s. 31 Spel & VN s. 33 Parodier & Fanlåtar s. 37 Vocaloid s. 39 Koreanskt & Kinesiskt s. 44 Västerländskt s. 51 Film & TV s. 54 Musikal & Opera Scanna QR-koden – få karaokelistan digitalt! Listan senast uppdaterad 2021-06-10 Karaoken presenteras av I samarbete med Hikari-kai, Sveriges J-rock-förening Raison d’être Pecena Piperka och Feed Me Kpop Den här är rejäl Jag minns inte exakt när det var jag tog över karaokelistan och databasen. När det var jag som började vara ansvarig för uppdateringarna. Det allra tidigaste beviset jag kan finna på en lista som det med hundraprocentig säkerhet var jag som stod för är från december 2014. Så jag har inte riktigt gjort det i ett decennium än. Men jag är rätt säker på att det här är den absolut största uppdateringen jag har gjort. I alla fall är det, utan minsta tvivel, den största uppdateringen på så här kort tid, eftersom det inte ens var två månader sedan den förra listan. Vi hade nämligen förra månaden ett litet event. En karaokemakartävling som löpte över fyra veckor. Summa summarum: Över hundra nya låtar i listan. Plus ett gäng uppdaterade versioner av sånt vi redan hade. Själv har jag se’n sist i princip bara gjort One Piece och Nichijou-låtar, så där finns det diverse nytt att hämta. Högst takt höll Nea, som dessutom fokuserade mycket på nyare populära serier. Så häri kan ni numera hitta musik från Tensei Shitara Slime Datta Ken, Re:Zero kara Hajimeru Isekai Seikatsu, Dr. -

KRIHVEL November 2009 Intervjuu Kihnu Virvega Küsisime Kohalikelt Teed Ning Jõudsimegi Õige K: Me Ei Tea

Varbla kooli ajaleht Nr.19 November 2009 Krihvel Kihnus 3.-5.juulil 2009.a. külastas Varbla kuid need, kes kohale olid tulnud, kooli õpilasomavalitsus ning kooli nautisid pidu väga. Meie ajalehetoimetus Kihnu saart. Meie reisiseltskond tantsis samuti eesmärgiks oli tutvuda kohaliku varaste hommikutundideni kahe eluga, külastada huvitavaid paiku, bändi - Scansi ja DefRage ning DJ TÄNA LEHES: vestelda saare elanikega ning muusikat nautides. võimaluse korral intervjueerida Teist päeva alustasime fotojahiga. kõigile eestlastele tuntud ja Õpilased jagunesid kahte • Intervjuu Kihnu armastatud laulumemme Kihnu võistkonda ning pidid ringi peale Virvega lk 2 Virvet. tegema peaaegu tervele saarele. Alustasime oma teekonda 3.juuli Ühel võistkondadest õnnestuski • Reisimuljeid lk 3 hommikul Munalaiu sadamast. selle matka ajal täita meie reisi • Lõpetajate Merereis oli tore, tormi polnud ja põhieesmärk - kohtuda Kihnu nii me randusimegi õnnelikult Virvega ning teda intervjueerida. meenutusi lk 4 Kihnu sadamas. Võtsime oma Kolmanda päeva hommikul • Intervjuu õp. matkavarustuse selga ning korrastasime oma laagripaiga, kõndisime päris pika ja väsitava tänasime meie võõrustajaid ilusa Rohtväliga lk 5 tee, kuni jõudsime sihtkohta - puhkuse ja meie majutamise eest • Arvamuslugu Raido tädi maja juurde. Sinna ning alustasimegi koduteed. kaunile heinamaale me oma Mõningad meenutused ning e-koolist lk 6 laagriplatsi üles panimegi. intervjuu Kihnu Virvega • An Cafe lk 7 Esimesel õhtul oli meie järgnevatel lehekülgedel ... meelelahtuseks noortepidu Kihnu rahvamajas. Rahvast oli küll vähe, Toimetus Kihnus käisid : Anna, Gerda, Liisi, Joonas, Joosep, Raido, Triinu, Lily, Getter, Marleen, Kaidy, Anna-Liisa, Biibe, Karl-Erik, Lea ja Karin Foto: Anna Vahter Lk.2 KRIHVEL November 2009 Intervjuu Kihnu Virvega Küsisime kohalikelt teed ning jõudsimegi õige K: Me ei tea. Mis koht sulle endale kõige rohkem kohani - Kihnu Virve koduni. -

ANIME OP/ED (TV-Versio) Japahari Net - Retsu No Matataki Maximum the Hormone - ROLLING 1000 Toon

Air Master ANIME OP/ED (TV-versio) Japahari Net - Retsu no matataki Maximum the Hormone - ROLLING 1000 tOON 07 Ghost Ajin Yuki Suzuki - Aka no Kakera flumpool - Yoru wa Nemureru kai? Mamoru Miyano - How Close You Are 91 Days Angela x Fripside - Boku wa Boku de atte ELISA - Rain or Shine TK from Ling Tosite Sigure - Signal Amanchu Maaya Sakamoto - Million Clouds 11eyes Asriel - Sequentia Ange Vierge Ayane - Arrival of Tears Konomi Suzuki - Love is MY RAIL 3-gatsu no Lion Angel Beats BUMP OF CHICKEN - Answer Aoi Tada - Brave Song .dot-Hack Lisa - My Soul Your Beats See-Saw - Yasashii Yoake Girls Dead Monster - My Song Bump of chicken - Fighter Angelic Layer .hack//g.u Atsuko Enomoto - Be my Angel Ali Project - God Diva HAL - The Starry sky .hack//Liminality Anime-gataris See-Saw - Tasogare no Umi GARNiDELiA - Aikotoba .hack//Roots Akagami no Shirayuki hime Boukoku Kakusei Catharsis Saori Hayami - Yasashii Kibou eyelis - Kizuna ni nosete Abenobashi Mahou Shoutengai Megumi Hayashibara - Anata no kokoro ni Akagami no Shirayuki hime 2nd season Saori Hayami - Sono Koe ga Chizu ni Naru Absolute Duo eyelis - Page ~Kimi to Tsuzuru Monogatari~ Nozomi Yamamoto & Haruka Yamazaki - Apple Tea no Aji Akagi Maximum the Hormone - Akagi Accel World May'n - Chase the World Akame ga Kill Sachika Misawa - Unite. Miku Sawai - Konna Sekai, Shiritakunakatta Altima - Burst the gravity Rika Mayama - Liar Mask Kotoko - →unfinished→ Sora Amamiya - Skyreach Active Raid Akatsuki no Yona AKINO with bless4 - Golden Life Shikata Akiko - Akatsuki Cyntia - Akatsuki no hana -

Obitel 2017 One Decade of Television Fiction in Ibero4america

IBERO-AMERICAN OBSERVATORY OF TELEVISION FICTION OBITEL 2017 ONE DECADE OF TELEVISION FICTION IN IBERO-AMERICA: ANALYSIS OF TEN YEARS OF OBITEL (2007-2016) IBERO-AMERICAN OBSERVATORY OF TELEVISION FICTION OBITEL 2017 ONE DECADE OF TELEVISION FICTION IN IBERO-AMERICA: ANALYSIS OF TEN YEARS OF OBITEL (2007-2016) Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes Guillermo Orozco Gómez General Coordinators Morella Alvarado, Gustavo Aprea, Fernando Aranguren, Alexandra Ayala-Marín, Catarina Burnay, Borys Bustamante, Giuliana Cassano, Pamela Cruz Páez, James Dettleff, Francisco Fernández, Gabriela Gómez, Pablo Julio, Mónica Kirchheimer, Charo Lacalle, Pedro Lopes, Guillermo Orozco Gómez, Juan Piñón, Rosario Sánchez, Luisa Torrealba, Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes National Coordinators © Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A., 2017 Capa: Letícia Lampert Projeto gráfico e editoração:Niura Fernanda Souza Produção editorial e revisão do texto: Felícia Xavier Volkweis Revisão gráfica:Niura Fernanda Souza Editores: Luis Antônio Paim Gomes, Juan Manuel Guadelis Crisafulli Foto de capa: Louie Psihoyos. High-definition televisions in the information era. Librarian: Denise Mari de Andrade Souza – CRB 10/960 D291 One decade of television fiction in Ibero-America: analysis of ten years of Obitel (2007-2016) / general coordinators Maria Immacolata Vassallo de Lopes and Guillermo Orozco Gómez. -- Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2017. 456 p.; ISBN: 978-85-205-0795-7 1. Television – Programs. 2. Fiction – Television. 3. Television programs – Ibero-American. 4. Media. 5. Television. I. Lopes, Maria Immacolata Vassallo de. II. Gómez, Guillermo Orozco. CDU: 654.19 659.3 CDD: 301.161 791.445 Direitos desta edição adquiridos por Globo Comunicação e Participações S.A. Editora Meridional Ltda. Av. Osvaldo Aranha, 440 cj. -

Accel World . Altima.Burst the Gravity

ANIME Serie Tipo Artista/Titulo OP Arrival of Tears 11 eyes ENDING Asriel - Sequentia (TV) Accel World . OP Altima.Burst The Gravity (TV) Air ENDING Lia - Farewell Song (TV) OP Air TV - Tori no Uta [VIDEO] Akame ga Kill! ENDING Miku Sawai - Konna Sekai, Shiritakunakatta (TV) OP Sora Amamiya - Skyreach (TV) Aldnoah Zero. OP Kalafina - Heavenly blue (TV) Amnesia. OP Nagi Yanagi - Zoetrope (TV) Angel Beats ENDING Aoi Tada - Brave Song (TV) INSERT SONG Girls Dead Monster - Answer Song INSERT SONG Girls Dead Monster - Thousand Enemies OP Lia - My Soul, Your Beats (TV) Angelic Layer. OP Atsuko Enomoto - Be My Angel Anohana OP Galileo Galilei - Aoi Shiori OP Galileo Galilei - Circle Game (TV) Another. OP Another. Ali Project - Kyoumu Densen (TV) OP Ali Project - Kyoumu Densen Ao no exorcist ENDING 2PM - Take Off ENDING Meisa Kuroki - Wired Life (TV) OP ROOKiEZ is PUNK'D - In My World (TV) OP Uverworld - Core Pride (TV) Aoki Hagane no Arpeggio OP nano feat. MY FIRST STORY - SAVIOR OF SONG OP nano feat. MY FIRST STORY - SAVIOR OF SONG (TV) ENDING Trident - Innocent Blue (TV) ENDING Trident - Blue Fields (TV) Arata Kangatari. OP Sphere - Genesis Aria (TV) OP Sphere - Genesis Aria Argevollen OP Kotoko - Tough Intention (TV) Arjuna ENDING Maaya Sakamoto – Mameshiba ENDING Maaya Sakamoto – Mameshiba (TV) ENDING Maaya Sakamoto - Sanctuary (TV) Asu No Yoichi. OP Meg Rock - Egao No Riyuu (TV) Avenger op. OP Ali Project - Gesshoku Grand Guignol (TV) Baka to Test to Shoukanjuu end.Milktub – ENDING Baka Go Home (TV) Bakumatsu Kikansetsu Irohanihoheto OP OP.FictionJunction YUUKA - Kouya Ruten (TV) OP OP.FictionJunction YUUKA - Kouya Ruten Bakumatsu Rock OP vistlip - Jack (TV) Basilisk ENDING BasiliskNana Mizuki - Wild Eyes (TV) OP Kouga ninpou chou (VIDEO) (Full version) OP Kouga ninpou chou (VIDEO) (TV version) Beck OP Hit in USA Beelzebub ENDING 9nine - Shoujo Traveler (TV) ENDING no3b - Answer (TV) ENDING Shoko Nakagawa - Tsuyogari (TV) Black bullet . -

Many Areas Continue to Benefit from Bilateral Ties

121st year | no. 42,271 ISSN 0289-1956 © THE JAPAN TIMES, LTD., 2017 60 years of Malaysia-Japan ties THUrsday, AUGUST 31, 2017 Many areas continue to benefit from bilateral ties MUSTAPA MOHAMED tal intensive and knowledge-based, while MINISTER OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE being export oriented. Investments and AND INDUSTRY, MALAYSIA collaboration in these areas would facili- tate the development of more innova- 2017 marks the 60th anniversary of dip- tive and creative Malaysian products and lomatic ties between Malaysia and Japan. services. This relationship may have begun as early Based on the successful outcomes of as the 15th century when the Melaka Sul- the LEP from 1982 to 2012, particularly in tanate traded with the Ryukyu kingdom. the human resource development, Malay- It was reaffirmed when Japan became one sia has continued with its second wave, of the earliest countries to establish an the LEP 2.0. It shall be even more eco- embassy in the newly independent Fed- nomically oriented with focus on green eration of Malaya. technologies, renewable energies and in Our trade history as a nation with key areas such as cutting-edge technology Japan can be traced all the way back to and innovation; high-tech skills develop- the 1970s. Japan’s industrialization strat- ment; high-end services development, egy created a high demand for Malay- ecosystem management with safe, reli- sian commodities then. In the 1980s, our able and renewable energy; small and bilateral relationship flourished when medium enterprises; and senior citizen policies, incentives and cooperation pro- programs. Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak and Prime Minister Shinzo Abe shake hands following a bilateral summit meeting in Tokyo on Nov. -

Enqvist Niina Maukonen Taru.Pdf (1.386Mt)

Niina Enqvist ja Taru Maukonen BOU ON POIKA JA PUKEE HAMEEN JA SE ON OK Japanilainen rockmusiikki Suomessa Opinnäytetyö Kulttuurituotannon koulutusohjelma Huhtikuu 2010 KUVAILULEHTI Opinnäytetyön päivämäärä Tekijä(t) Koulutusohjelma ja suuntautuminen Niina Enqvist ja Taru Maukonen Kulttuurituotannon koulutusohjelma Nimeke Bou on poika ja pukee hameen ja se on ok – Japanilainen rockmusiikki Suomessa Tiivistelmä Opinnäytetyön tavoite oli selvittää j-rockin osaa suomalaisessa nuorisokulttuurissa. Opinnäytetyössä tutkittiin harrastajamääriä, taloudellisia mahdollisuuksia, ilmiön kestävyyttä sekä muuntautumista suo- malaisiin olosuhteisiin sopivaksi. Tutkimus pyrki ymmärtämään ilmiön luonnetta, sen syitä ja seurauksia sekä samalla nuorisoa ja heidän motiivejaan. J-rockista ei ole juurikaan tehty aikaisempia tutkimuksia Suomessa. Tutkimuksella pyrittiin osoittamaan j-rockin mahdollisuudet Suomessa niin markkinoiden näkökulmasta mutta myös suomalaista nuorisokulttuuria rikastuttavana tekijänä. Tutkimuksessa selvitettiin harrastajakunnan lähtökohdat, kuten ikä, paikkakunta, sukupuoli ja kuinka vahva kiinnostus harrastuneisuuteen on. Harrastajakuntaa selvitettiin kahdella erillisellä kyselyllä, Web- ropol-alustalla toteutettu monivalintakysely sekä vapaamuotoinen sähköpostikysely, jolloin pystyttiin profiloimaan keskivertoharrastaja. Molemmissa kyselyissä ilmeni yhtäläisyyksiä, jotka on pyritty huomi- oimaan työssä. Kyselyssä saatujen tietojen mukaan pystyttiin hahmottamaan harrastajien kulutustottumuksia oheistuot- teiden, konserttien ja levyjen -

We Still Have Not Overcome Saugus Driver Dies After Horrific Crash Snow

MONDAY, JANUARY 21, 2019 ITEM PHOTO | OWEN O’ROURKE ITEM PHOTO | OWEN O’ROURKE Snow nally makes Saugus driver dies its 2019 debut after horri c crash By Gayla Cawley Newhall Street in By Gayla Cawley This car, now at the ITEM STAFF Lynn was plowed, but ITEM STAFF bottom of a 40-foot sleet made driving embankment, rst Winter got off to a slow start this year, but accu- treacherous all day. SAUGUS — A driver has died after crashing a car smashed through the mulating snow made its unwelcome debut on the through a garage at a Hammersmith Drive home, back wall of a garage North Shore Sunday. falling off a cliff and tumbling down a 40-foot em- at 31 Hammersmith Lynn and surrounding communities only saw a bankment on Sunday afternoon. Drive Sunday in few inches in the early morning hours, but it was The driver had to be extricated from the car by the hours of sleet and freezing rain that followed Saugus Fire crews following a crash that ended Saugus. that caused headaches for Department of Public with the car on its roof. There were no passengers Works crews and residents trying to clean up the in the car. mess. Police have not identi ed the driver, who was tak- It was unclear if a fatal crash in Saugus on Sun- en to a local hospital and later pronounced dead. day afternoon, in which a person died after driving Saugus Police and Fire responded to the crash at a car through a garage and tumbling off a cliff and 31 Hammersmith Drive at about 1:30 p.m.