On CUSTOMS & COFFINS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ÍNTER R "Iraveí(|)Ííhouítñou0íe

.t.-:===.-._^=^.-. ==!l IJMoorc, Mr. and Mrs. William Pcheer, Bacon, of New York, were the of East Orange, and Mr. W. M. among Mrs. Louis F. es LentenExodusFromNew The Goss. arrivals at the Ponce do Leon for the I Prankard and W. H. Don- of the German government are filled York woman's Atlantic nat Is Pell are Belieair championship of the week-end, afterward going to Palm City among the New York pa¬ Gotha Almanack with the usual array of excellencies, Golf Links will begin on Mon- Beach. trons of the Marlborough-Blenheim. I professors and councillors, yet at the day. Mrs. G. K. Morrow, of Malba, L. Mr. and Mrs. Malcolm J. A. Liss- head of thai government stand the L, has been ill and Mrs. Frederick Wood MeMeeker, of Winter Home for Will Fill Winter Resorts her may not defend New Y'ork, entertained at the Alcazar J berger and Mr. and Mrs. Hugo Yieth Can't With names of i bert, Scheidemann, Ditt- Up title. Other New Yorkers who ! and their daughter are at the Shel- KeepUp mann, and Barth. Nobody at dinner the Landsberg will are Mis? early part of the week. burne phi,;," M#trion Kerr, Mrs. From New York at the Hotel Alcazar New from New York. Mr. and Mrs. is supposed to care about their Chris- W. H. Ellis, Miss »ienevive Yorkers Robert of tian names. Mrs. R. Cullen, are Mr. and Mrs. William Holcomb, Many Brockway, Summit, arrived Deposed Royalty S. Porter, Miss Hazel Hop- Mrs. A. E, Mrs. at the Dennis, accompanied by Miss Tiie German national colors are still Seekers of Freedom, From Cold kins, Mrs. -

Collection Development Policy 2012-17

COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT POLICY 2012-17 CONTENTS Definition of terms used in the policy 3 Introduction 5 An historical introduction to the collections 8 The Collections Archaeology 11 Applied and Decorative Arts 13 Ceramics 13 Glass 14 Objets d‘Art 14 Jewellery 15 Furniture 16 Plate 16 Uniforms, Clothing and Textiles 17 Flags 18 Coins, Medals and Heraldry 20 Coins and Medals 20 Ship Badges, Heraldry and Seal Casts 21 Ethnography, Relics and Antiquities 23 Polar Equipment 23 Relics and Antiquities 23 Ethnographic Objects 24 Tools and Ship Equipment 26 Tools and Equipment 26 Figureheads and Ship Carvings 27 Cartography 30 Atlases, Charts, Maps and Plans 30 Globes and Globe Gores 31 Fine Arts 33 Oil Paintings 33 Prints and Drawings 34 Portrait Miniatures 35 Sculpture 36 Science and Technology 40 Astronomical Instruments 40 Navigational Instruments and Oceanography 42 Horology 43 Weapons and Ordnance 46 Edged Weapons 46 Firearms 47 Ordnance 49 Photographs and Film 52 Historic Photographs 52 Film Archive 54 Ship Plans and Technical Records 57 1 Boats and Ship Models 60 Boats 60 Models 60 Ethnographic Models 61 Caird Library and Archive 63 Archive Collections 63 Printed Ephemera 65 Rare Books 66 Legal, ethical and institutional contexts to acquisition and disposal 69 1.1 Legal and Ethical Framework 69 1.2 Principles of Collecting 69 1.3 Criteria for Collecting 70 1.4 Acquisition Policy 70 1.5 Acquisitions not covered by the policy 73 1.6 Acquisition documentation 73 1.7 Acquisition decision-making process 73 1.8 Disposal Policy 75 1.9 Methods of disposal 77 1.10 Disposal documentation 79 1.11 Disposal decision-making process 79 1.12 Collections Development Committee 79 1.13 Reporting Structure 80 1.14 References 81 Appendix 1. -

PANGBOURNIAN the Magazine of the OP Society No 51 2021

THE PANGBOURNIAN The magazine of the OP Society No 51 2021 IN THIS ISSUE: • The College in the year of Covid • OPs and the pandemic • 25 years of co-education • Remembering World War 2 • News of OPs H1832-Pangbournian v4.indd 1 03/02/2021 10:49 THE TWO MESSAGES - FROM OUR 2020 AND 2021 CHAIRMEN AN HONOUR AND A long in the memories of those that PANGBOURNIAN were able to attend. I have no doubt The magazine of the OP Society No 51 2021 GREAT MEMORY that, when we are able to return to a form of normality, the planned Falklands weekend event will be every bit as enjoyable and memorable. It was unfortunate for me that the CONTENTS Covid-19 pandemic brought to an all- too early conclusion my participation OP Society fulfilling an increasingly 3 Welcome From the OP Society Chairmen, the in an array of events which had to be significant purpose for both the Chairmen of the Board of Governors, and the Headmaster cancelled but which usually I would College and especially younger OP’s have attended. We can only hope of both genders. Given that this latest The last few years acting as 7 News 9 14 that everything will return to as near edition of the OP Magazine marks the By and about Old Pangbournians in 2020 Chairman of the OP Society have to normal as possible before long. 25th Anniversary of co-education at been a privilege,” writes DAVID In the meantime, Phillip Plato has the College, I do hope more female 12 OP Clubs NICHOLSON (64-68). -

To the Islands: Photographs of Tropical Colonies in the Queenslander

QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Quanchi, Max (2008) To the islands : photographs of tropical colonies in The Queenslander. In: 18th Pacific History Association Conference, December 2008, University of the South Pacific, Suva. © Copyright 2008 [please consult the author] 1 ABSTRACT Australian readers knew a great deal about the Pacific Islands in the early 20th century. This understanding came from missionary fund-raising campaigns, visiting lantern-slide lecturers, postcards, and illustrated books and encyclopaedia but most of all, after the mid-1890s, from heavily illustrated weekend newspapers. These were published in all major cities and offered a regular visual window on ‘the islands”, three of which had become Australian colonies shortly after WW1. This paper argues that Australians were well-informed about settlement, economic opportunity and the life of Island peoples, but that it was a view affected by visual tropes and romantic notions and the hegemonic posturing of those who thought the western Pacific should become an Australian or at least a British sphere of interest. 2 To the Islands; photographs of tropical colonies in The Queenslander Between 1898 and 1938, The Queenslander, a weekend, pictorial newspaper published in Brisbane, provided an intimate, continuous photographic gallery of the European colonial frontier and the peoples and cultures of the western Pacific, publishing 2000 black and white photographs of the Pacific Islands, Torres Strait and Australian South Sea Islanders (then known as kanakas).1 Readers of The Queenslander Pictorial, an eight-page section of the newspaper, were offered “Around the Coral Sea”, over nine weekends in November and December 1906, a gallery of 78 photographs of the Shortland Islands, Samarai, Woodlark Islands, Solomon Islands, Poporang Mission in New Guinea and four full-page feature photomontages on the repatriation of Kanaka labourers. -

Naval Accidents 1945-1988, Neptune Papers No. 3

-- Neptune Papers -- Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945 - 1988 by William M. Arkin and Joshua Handler Greenpeace/Institute for Policy Studies Washington, D.C. June 1989 Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 Overview ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Nuclear Weapons Accidents......................................................................................................... 3 Nuclear Reactor Accidents ........................................................................................................... 7 Submarine Accidents .................................................................................................................... 9 Dangers of Routine Naval Operations....................................................................................... 12 Chronology of Naval Accidents: 1945 - 1988........................................................................... 16 Appendix A: Sources and Acknowledgements........................................................................ 73 Appendix B: U.S. Ship Type Abbreviations ............................................................................ 76 Table 1: Number of Ships by Type Involved in Accidents, 1945 - 1988................................ 78 Table 2: Naval Accidents by Type -

ARBON, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/7 Special List ______

_____________________________________________________________________________________ ARBON, Anthony Lyle PRG 1190/7 Special list _____________________________________________________________________ 1. World. Ships menus. (Australia and World) Arranged alphabetically by name of ship. See Item List for PRG 1190/7/1 Box 1 A-Z 2. Australia. Cruise brochures, including passenger accommodation and deck plans and miscellaneous maritime publications. Arranged alphabetically by company name and ships name. See Item List for PRG 1190/7/2. Box 1 A-Z 3. World. Cruise brochures, including passenger accommodation and deck plans and miscellaneous maritime publications. Arranged alphabetically by company name and ships name. (e.g. CUNARD – ‘QUEEN ELIZABETH’) See Item List for PRG 1190/7/3. Box 1 A-CHA Box 2 CHI-CTC Box 3 CUNARD (shipping company) Box 4 CY-HOL Box 5 I-O Box 6 P&O (shipping company) Box 7 P&O Orient Line (shipping company) Box 8 PA-SIL Box 9 SITMAR (shipping company) Box 10 SO-Z PRG 1190/7 Special list Page 1 of 14 _____________________________________________________________________________________ Part 1 : World ships menus M.V. Akaroa R.M.S. Moldavia M.V. Aranda S.S. Ocean Monarch Arcadia T.S.S. Nairana M.N. Australia S.S. Orcades T.S.S. Awatea S.S. Oriana R.M.S. Baltic M.V. Ormiston M.V. Britannic R.M.S. Ormuz S.S. Canberra S.S. Oronsay T.V. Castel Felice S.S. Orsova M.V. Charon Prinz-Regent Luitpold Q.S.M.V. Dominion Monarch R.M.S. QE2 “Queen Elizabeth 2” T.S.M.V. Duntroon R.M.S. Rangitata M.V. Fairsea M.S. Sagatjord T.V. -

Woc Issue65.Indd

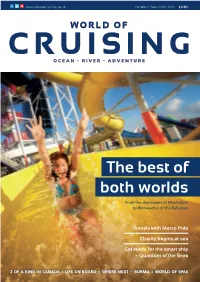

www.worldofcruising.co.uk October / November 2014 £4.50 WORLD OF CRUISING October / November 2014 Issue 65 October / The best of both worlds From the skyscrapers of Manhattan to the beaches of the Bahamas www.worldofcruising.co.uk @WorldofCruising www.worldofcruising.co.uk Travels with Marco Polo Charity begins at sea Get ready for the smart ship – Quantum of the Seas 3 OF A KIND IN CANADA + LIFE ON BOARD + WHERE NEXT – BURMA + WORLD OF SPAS EDITOR’S LETTER 1 WORLD OF CRUISING OUR CONTRIBUTORS GARY BUCHANAN, our Contributing Editor, is one of cruising’s most distinguished writers, contributing regularly to national newspapers, and the author of three books on the QE2. He was the winner of the Best River Cruise Feature category in this year’s CLIA cruise journalism awards for his World of Cruising article on the Zambezi Queen. JO FOLEY is a renowned author and journalist as well as our World of Spas editor, having previously edited Woman, Options, and The Observer magazine. She travels worldwide in search of the latest spa and beauty news and reports back on the most blissful hideaways to enjoy. GREG BARBER likes to think of himself as an international man of mystery. He has Italian roots – some of which were once heavily tinted – and now spends most of his time jet-setting around the world, trying to shake off his paymasters and his creditors. WELCOME ABOARD LESLEY BELLEW got hooked on adventure cruising in 2008 and now travels the globe chasing stories and It seems like only yesterday I was putting the finishing sunshine. -

Chronology of Naval Accidents 1945 to 1988

Chronology of Naval Accidents 1945 to 1988 This file is copyright to "Neptune Paper No. 3: Naval Accidents 1945-1988" a USA Compilation which we acknowledge fully, and moreover appreciate as an historic document. The following is an extract from their excellent file which has been reprocessed to include:- a. Correction of any typing errors. b. Inclusion of additional data. c. Conversion of date presentations from US to English. d. Changes in spelling from US to English. e. Changes in grammer from US to English. f. Ship type and classes added. At no stage was it intended to alter the purport of the original document which for US surfers remain as scripted in the said Neptune Paper 3. All we set out to do was to make the document easier to be read by an English person without altering the original historic value which in common with all, we value and learn from. Thank you. Serial Date Description of Accident Type of vessel No. 1 01/Feb/45 In February the USS Washington (BB-56) and USS Indiana (BB- BB=Battleship 58) collide in the Pacific. 2 08/Feb/45 A U.S. Navy minesweeper sinks after colliding with a U.S. destroyer off Boston Harbour, Massachusetts. 3 17/Mar/45 A new submarine floods and sinks after a worker opens a torpedo tube at the Boston Navy Yard. 4 09/Apr/45 A U.S. Liberty ship loaded with aerial bombs explodes, setting three merchant ships afire and causing many casualties in Bari harbour, Italy. 5 09/Apr/45 The Allied tanker Nashbulkcollides with the U.S. -

RCHS Chronology of Modern Transport in the British Isles 1945

RCHS Chronology of Modern Transport in the British Isles 1945–2015 Introduction This chronology is intended to set out some of the more significant events in the recent history of transport and communication, with particular reference to public transport, in the British Isles since the end of 1944. It cannot hope to cover the closure or opening of every branch railway or canal, the sale of every bus company, nor the coming and going of every pertinent office holder. The hope is that it does contain details of the principal legislative and organisational changes affecting transport – in particular the shifts between private and public ownership which have characterised the industry within this period – together with some notable ‘firsts’, ‘lasts’ and other significant events, especially those which exhibit trends. A very few overseas events are included (in italics), either because they had a British relationship, or for comparative purposes. Conventions Dates are, where appropriate, the first or last occasion on which an ordinary member of the public could make full use of the facility: official and partial openings on different dates are in general confined to parentheses; and ‘closed with effect from’ (wef) dates are quoted only where the actual last day of service has not been certainly established. Dates assigned to statutes are those of assent unless stated otherwise. ‘First’, ‘last’ or similar qualifiers mean ‘in Britain’ unless otherwise indicated. ‘Commercial’ is used, rather loosely, as a qualifier to exclude experimental, enthusiast, heritage, leisure or similar operations. Forms of name are those in use at the date of the event. -

Golda Meir Dies; Didn't See Peace

‘ -;jp PAGE TWENTY-EIGHT - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester. Conn., Fri., Dec. 8, 1978 Manchester Suntava to Robert L. Walsh, property at Ronald E. Dixon to Roger N. Leege and tVriifirule of ullurliinenl minster Construction Corp. and First Harbor Sign Service for Sterling 23-25 Cooper St., J64,500. Leslie F. Leege, both of Coventry, Trustees of Roofers Local Welfare, Hartford Realty Corp, Printery, sign at 513 Middle Turnpike, Public Records 3-S Construction Inc. to Rudolph E. property at 21 Kensington St.. 345,250. Pension and Vacation Trusts, Hartford, ItuiltlinK |>eriiiilH 3131. Richard C. Adam and Sandra J. Adam Capello Sr. and Joan B. Capello, both of against McConvyyjg^^^Atefing S c Sheet Yankee Homes Inc., home at 48 Bobby > ' ■ to John A. Marin, property at 130-132 Oak .Murriugc liceiini- South Windsor, property at 46 Sass Drive Metal Inc,, RinKari J. ^C onville and Lane, 336,000. Yankee Homes Inc., home U urranly 186,500. St., 346.75 conveyance tax. John H. Vannie III and Myla Dee Family Warm Again Dems Cheer Carter, Group of Pioneers Wizened Potatoes Nutmeg Homes Inc. to John C. Honor Barbara M. McQ)nville and John McCon- at 75 Bobby Lane, 336,000. B.ikcr. both of Manchester, Dec. 12. Estate of Mark T. Urbanetti to Alex T. Juilgiiiriil lien ville, 310.000, property at 99 Keeney St. Harry M. Fine, West Hartford, un and Vivian J. Honor, property at 103 Kent Urbanetti, John S. Urbanetti and Hollis After Furnace Fire Promise Sex Equality On Way to Australia Deserve Attention Drive, 177,620. W.H. -

• 5 NEWSLETTER April 2020

• 5 NEWSLETTER April 2020 Hello Gents, this month’s newsletter is quite different from the usual read, primarily because there is no news! We have been on the official lockdown for nearly three weeks now, and I know some have been on their self imposed isolation for longer. I have not heard to the contrary so hope everyone is keeping well and trying to keep occupied. In a previous message I said if anyone needed anything delivering, I would be pleased to help but I am following guide lines and now not going out unnecessarily. I think people will now be aware of all the delivery services from individuals and business’s “stepping up to the mark”. It is at times like these that we can appreciate how fortunate we are living in this area. Thanks to the people who have contributed towards this publication, and Nevile for collating and sending it out. Who knows how long this situation will last, but I think it’s fair to say it will be a few months before normal service is resumed? Any contribution towards another letter in another six weeks (or so) time would be most welcome. I have never typed as much in my whole life! Hopefully this edition will give members ideas for contributions to editions of the newsletter for the future month(s). Some members felt that it was good idea to keep the newsletter going because it helps people keep in touch and hopefully keeps up morale in these unprecedented times. One idea suggested was that people discuss and provide photos of a favourite model build, interesting engineering experiences or even recommend books or magazine articles that have inspired them in their modelling. -

Swan IV, Sail Making Supplement Review by Don Dressel

1 Newsletter Volume 42, Number 5, May 2015 Contacts Work in Progress President: Bill Schultheis (714) 366-7602 April 15, 2015 E-Mail: [email protected] Reporter: Dave Yotter Vice President: Don Dressel Your editor wishes to thank those who took his (909) 949-6931 place while he went to visit the ROPE and attend the th E-Mail: [email protected] ROPE 40 Symposium and Exposition in Tokyo, Japan. Secretary: Paul Payne In particular, Bill Russell, who took all the pictures (310) 544-1461 included with this Work in Progress report. Thank you, Treasurer: Mike DiCerbo Bill. (714) 523-2518 15320 Ocaso Ave, #DD204, IAAC Yacht USA 76 – Hank Tober La Mirada, CA. 90630 Editor, Don Dressel (909) 949-6931 908 W. 22nd Street Upland, CA 91784-1229 E-mail: [email protected] Web Manager: Doug Tolbert: (949) 644-5416 Web Site www.shipmodelersassociation.org Meeting – Wed., May 20, 7 PM, Red Cross Building, 1207 N. Lemon, Fullerton, CA. 92832 USA 76 is an American International America’s Cup Class yacht. It was used by the Oracle BMW Racing Officers meeting –Wed., June 3, Team in their preparations to challenge for the 2003 2015, 7 PM, Bob Beech’s house, America’s Cup held in Auckland, New Zealand. ORACLE 130 Clove Pl., Brea, CA. 92821 – would go through to the Louis Vuitton Challenger Series (714) 529-1481. final and come up against the formidable Team Alinghi from Switzerland. Alinghi, ultimately won the Cup after an impressive performance. In September 2003, ORACLE arranged for a “rematch” to be held against Alinghi in San Francisco.