Safety and Efficacy of Testosterone for Women: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trial Data

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(12) STANDARD PATENT (11) Application No. AU 2015336929 B2 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE

(12) STANDARD PATENT (11) Application No. AU 2015336929 B2 (19) AUSTRALIAN PATENT OFFICE (54) Title Methods of reducing mammographic breast density and/or breast cancer risk (51) International Patent Classification(s) A61K 31/568 (2006.01) A61K 31/585 (2006.01) A61K 31/4196 (2006.01) A61P 35/00 (2006.01) A61K 31/5685 (2006.01) A61P 43/00 (2006.01) (21) Application No: 2015336929 (22) Date of Filing: 2015.10.22 (87) WIPO No: W016/061615 (30) Priority Data (31) Number (32) Date (33) Country 62/067,297 2014.10.22 US (43) Publication Date: 2016.04.28 (44) Accepted Journal Date: 2021.03.18 (71) Applicant(s) Havah Therapeutics Pty Ltd (72) Inventor(s) Birrell, Stephen Nigel (74) Agent / Attorney Adams Pluck, Suite 4, Level 3 20 George Street, Hornsby, NSW, 2077, AU (56) Related Art WO 2002/009721 Al MOUSA, N.A. et al. "Aromatase inhibitors and mammographic breast density in postmenopausal women receiving hormone therapy" Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society (2008) Vol.15 No.5, pages 875 to 884 WO 2009/036566 Al SMITH, J. et al. "A Pilot Study of Letrozole for One Year in Women at Enhanced Risk of Developing Breast Cancer: Effects on Mammographic Density" Anticancer Research (2012) Vol.32 No.4, pages 1327 to 1332 OUIMET-OLIVA, D. et al. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal (1981) Vol.32 No.3, pages 159 to 161 (see online PubMed Abstract PMID: 7298699) (12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International -

Annex D to the Report of the Panel to Be Found in Document WT/DS320/R

WORLD TRADE WT/DS320/R/Add.4 31 March 2008 ORGANIZATION (08-0902) Original: English UNITED STATES – CONTINUED SUSPENSION OF OBLIGATIONS IN THE EC – HORMONES DISPUTE Report of the Panel Addendum This addendum contains Annex D to the Report of the Panel to be found in document WT/DS320/R. The other annexes can be found in the following addenda: – Annex A: Add.1 – Annex B: Add.2 – Annex C: Add.3 – Annex E: Add.5 – Annex F: Add.6 – Annex G: Add.7 WT/DS320/R/Add.4 Page D-1 ANNEX D REPLIES OF THE SCIENTIFIC EXPERTS TO QUESTIONS POSED BY THE PANEL A. GENERAL DEFINITIONS 1. Please provide brief and basic definitions for the six hormones at issue (oestradiol-17β, progesterone, testosterone, trenbolone acetate, zeranol, and melengestrol acetate), indicating the source of the definition where applicable. Dr. Boisseau 1. Oestradiol-17β is the most active of the oestrogens hormone produced mainly by the developing follicle of the ovary in adult mammalian females but also by the adrenals and the testis. This 18-carbon steroid hormone is mainly administered as such or as benzoate ester alone (24 or 45 mg for cattle) or in combination (20 mg) with testosterone propionate (200 mg for heifers), progesterone (200 mg for heifers and steers) and trenbolone (200 mg and 40 mg oestradiol-17β for steers) by a subcutaneous implant to the base of the ear to improve body weight and feed conversion in cattle. The ear is discarded at slaughter. 2. Progesterone is a hormone produced primarily by the corpus luteum in the ovary of adult mammalian females. -

Case: Management Issues

Volume 9, Issue 1 (January 2013) This clinical e-newsletter from The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) presents questions and cases commonly seen in a menopause specialist’s practice. Recognized experts in the field provide their opinions and practical advice. Wen Shen, MD, MPH, the Editor of Menopause e-Consult, encourages your suggestions for future topics. Note that the opinions expressed in the commentaries are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by NAMS or Dr. Shen. Case: products were used by women in 2003.2 A patient requests your advice about Presumably, this approach to the aging US testosterone from a compounding pharmacy to female population and the increasing 3 supplement her hormone therapy. How should prevalence of low sexual desire with age you advise her? Are there any guidelines for augments demand for testosterone products for 4,5 dosing testosterone ordered from these women. As demonstrated in these reviews, pharmacies? evidence documents that testosterone treatment (local/clitoral, vaginal, and systemic) increases Management issues by: sexual desire and genital sensitivity, and might improve the intensity of orgasm. Prospective, James A. Simon, MD, CCD, randomized, clinical trials of a testosterone NCMP, FACOG patch developed specifically for women Clinical Professor, Department demonstrated a statistically significant increase of Ob/Gyn George Washington University in the number of satisfying sexual events and School of Medicine improved desire, arousal, orgasm, pleasure, Women’s Health & Research ® responsiveness, and self-image—while Consultants Washington, DC decreasing sexual concerns and distress. These findings were consistent in surgically and naturally menopausal women already on The controversy over compounding rages on. -

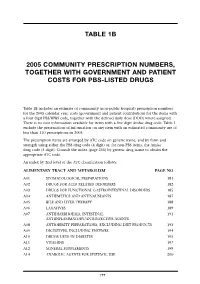

Table 1B 2005 Community Prescription Numbers, Together with Government

TABLE 1B 2005 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS-LISTED DRUGS Table 1B includes an estimate of community (non-public hospital) prescription numbers for the 2005 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 exclude the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2005. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Consult the index (page 255) by generic drug name to obtain the appropriate ATC code. An index by 2nd level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM PAGE NO A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 181 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 182 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 185 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 187 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 188 A06 LAXATIVES 189 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL 191 ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVE AGENTS A08 ANTIOBESITY PREPARATIONS, EXCLUDING DIET PRODUCTS 193 A09 DIGESTIVES, INCLUDING ENZYMES 194 A10 DRUGS USED IN DIABETES 195 A11 VITAMINS 197 A12 MINERAL SUPPLEMENTS 199 A14 ANABOLIC AGENTS FOR SYSTEMIC USE 200 177 BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS B01 ANTITHROMBOTIC AGENTS 201 B02 ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS 203 B03 -

Hormone Therapy with Pellet Implants

DATA: Hormone Therapy with Pellet Implants Hormone replacement therapy by pellet implantations has been used with great success in the United States, Europe and Australia since 1938 and found to be superior to other methods of hormone delivery (Greenblatt 49, Mishnell 41, Cantril 84, Stancyzyk 88). It is not experimental. Pellets deliver consistent, physiologic levels of hormones and avoid the fluctuations of hormone levels seen with other methods of delivery (Greenblatt 49, Thom81, Cantril 84, Stancyzyk 88). Hormones delivered by the subcutaneous implants by pass the liver, do not affect the clotting factors and do not increase the risk of thrombosis (Notelovitz 87, Seed 00). Bioidentical testosterone delivered subcutaneously by pellet implant is cardiac protective, unlike oral, synthetic testosterone (Sands 97, Worboys 00). Testosterone delivered by pellet implantation, does not adversely affect blood pressure, lipid levels, glucose or liver functions (Burger 84, Farish 84, Fletcher 86, Barlow 86, Notelovitz 84, Stanczyk 88, Davis 95, 00, Handelsman 96, Sands 97, Seed 00, Cravioto 01). In addition, testosterone is a vasodilator (Perusquia 10). Pellets are superior to oral and topical hormone therapy with respect to relief of menopausal symptoms (Staland 78, Cardoza 84). Testosterone implants have consistently been shown to improve insomnia, sex drive, libido, hot flashes, palpitations, headaches, irritability, depression, aches, pains, and vaginal dryness (Glaser 11, Statland 78, Thom 81, Brincat 84, Davis 95,00 Cravioto 01). Hormone replacement therapy with estradiol and testosterone implants is superior to oral and topical (both the patch and gel) hormone replacement therapy for bone density (Savvas 88,92, Davis 95, Anderson 97). The consistent, adequate levels of testosterone delivered by pellet implant are important in maintaining bone mineral density (Aminoroaya 05) while also being available as a substrate for the production of estradiol (Simpson 02, 03). -

Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Inc. Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO) Student Blanket Health Plan Drug Formulary

Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, Inc. Exclusive Provider Organization (EPO) Student Blanket Health Plan Drug Formulary Effective September 1, 2021 Health Plan Products: Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, EPO Student Blanket Health Plan offered by Kaiser Permanente Insurance Company For the most current list of covered medications or for help understanding your KPIC insurance plan benefits, including cost sharing for drugs under the prescription drug benefit and under the medical benefit: Call 1-800-533-1833, TTY 711, Monday through Friday, 7 a.m. to 9 p.m. ET Visit kaiserpermanente.org to: • Find a participating retail pharmacy by ZIP code. • Look up possible lower-cost medication alternatives. • Compare medication pricing and options. • Find an electronic copy of the formulary here. • Get plan coverage information. For cost sharing information for the outpatient prescription drug benefits in your specific plan, please visit kp.org/kpic-websiteTBD The formulary is subject to change and all previous versions of the formulary are no longer in effect. Kaiser Permanente Last updated: September 1, 2021 Table of Contents Informational Section...........................................................................................................................................3 ANTIHISTAMINE DRUGS - Drugs for Allergy.....................................................................................................9 ANTI-INFECTIVE AGENTS - Drugs for Infections........................................................................................... -

Effect of Ovarian Hormone Therapy on Cognition in the Aged Female Rhesus Macaque

10416 • The Journal of Neuroscience, October 5, 2016 • 36(40):10416–10424 Behavioral/Cognitive Effect of Ovarian Hormone Therapy on Cognition in the Aged Female Rhesus Macaque Steven G. Kohama,1 XLauren Renner,1 Noelle Landauer,1 XAlison R. Weiss,2 Henryk F. Urbanski,1,3 XByung Park,4 Mary Lou Voytko,5 and Martha Neuringer1 1Division of Neuroscience, Oregon National Primate Research Center, Oregon Health and Science University, Beaverton, Oregon 97006-3448, 2Department of Psychology, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, 3Department of Behavioral Neuroscience, Oregon Health and Science University, Portland, Oregon 97239-3098, 4School of Public Health, Oregon Health and Science University and Portland State University, Portland, Oregon 97239-3098, and 5Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy and the Interdisciplinary Program in Neuroscience, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27157-1010 Studiesoftheeffectofhormonetherapyoncognitivefunctioninmenopausalwomenhavebeenequivocal,inpartduetodifferencesinthe type and timing of hormone treatment. Here we cognitively tested aged female rhesus macaques on (1) the delayed response task of spatial working memory, (2) a visuospatial attention task that measured spatially and temporally cued reaction times, and (3) a simple reaction time task as a control for motor speed. After task acquisition, animals were ovariectomized (OVX). Their performance was compared with intact controls for 2 months, at which time no group differences were found. The OVX animals were then assigned to treatment with either a subcutaneous sham implant (OVX), 17- estradiol (E) implant (OVXϩE) or E implant plus cyclic oral proges- terone (OVXϩEP). All groups were then tested repeatedly over 12 months. The OVXϩE animals performed significantly better on the delayed response task than all of the other groups for much of the 12 month testing period. -

A221102 Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Study Of

A221102 ALLIANCE FOR CLINICAL TRIALS IN ONCOLOGY Randomized Double-Blind Placebo Controlled Study of Testosterone in the Adjuvant Treatment of Postmenopausal Women with Aromatase Inhibitor Induced Arthralgias Study Chairs: Charles L. Loprinzi, M.D. (Research Base)* Mayo Clinic Study Co-chair: Statistician: Drug Availability Supplied Agent: Testosterone IND #114707 (Alliance) *Investigator having NCI responsibility for this protocol √ Study contributor(s) not responsible for patient care. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01573442 Participating NCTN Organizations Alliance/ Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology (lead) ECOG-ACRIN/ ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group NRG/ NRG Oncology SWOG/ SWOG 1 NCI Version Date: 10/09/2018 Update #6 Alliance A221102 Cancer Trials Support Unit (CTSU) Contact Information For regulatory requirements: For patient enrollments: For Study data submission Regulatory documentation must Please refer to the patient Legacy NCCTG sites will submit be submitted to the CTSU via enrollment section of the electronic CRFs via: the Regulatory Submission protocol for instructions on using NCCTG Remote Data Entry Portal. the Oncology Patient Enrollment System. Regulatory Submission Portal: Network (OPEN) which can be (Sign in at www.ctsu.org, and accessed at Sites not previously affiliated select the Regulatory https://www.ctsu.org/OPEN_SY with NCCTG will submit paper Submission sub-tab under the STEM/ or CRFs to: Regulatory tab.) https://OPEN.ctsu.org. Alliance Statistics and Data Center Institutions with patients waiting Contact the CTSU Help Desk Attention: that are unable to use the Portal with any OPEN-related should alert the CTSU questions at Regulatory Office immediately at to receive further instruction and support. Do not submit study data or forms to CTSU Data Operations. -

STANDARDIZED PROCEDURE Subcutaneous Medication Implant: Insertion (Adult, Peds)

STANDARDIZED PROCEDURE Subcutaneous Medication Implant: Insertion (Adult, Peds) I. Definition Subcutaneous Implant Insertion A. Definition of Subcutaneous Implant: an under-the-skin (subcutaneous) implantable device that contains medication which is slowly released over an extended period of time. The most common classes of drugs for the subcutaneous implant procedure are: B. Etonogestrel implant: a single rod, progestin-only subdermally implantable device that provides effective contraception for up to 3 years. C. Histrelin Acetate implant: a single rod, histrelin acetate subdermally implantable device that provides effective suppression of LH/FSH for up to 1 year in children with central precocious puberty (CPP). II. Background Information A. Setting: The setting (inpatient vs outpatient) and population (pediatrics) for the Advanced Health Practitioner (AHP) is determined by the approval of the privileges requested on the AHP Privilege Request Form. If the procedure is being done on a Pediatric patient, make sure Child Life is involved and use age appropriate language and age appropriate developmental needs with care of children, as appropriate to the situation. B. Training/Supervision: All health care professionals, including AHPs, should receive instruction and training prior to performing insertion of the subcutaneous implant. Nexplanon® (etonogestrel) requires completion of the clinical training program from Merck prior to performing insertion of the subcutaneous implant. The necessity of this procedure will be determined by the Advanced Health Practitioner in collaboration with the supervising physician or his/her designee. Designee is defined as another attending physician who works directly with the supervising physician and is authorized to supervise the Advanced Health Practitioner. Direct supervision will not be necessary once competency is determined, as provided for in the procedure. -

2020 Aetna Standard Plan

Plan for your best health Aetna Standard Plan Aetna.com Aetna is the brand name used for products and services provided by one or more of the Aetna group of subsidiary companies, including Aetna Life Insurance Company and its affiliates (Aetna). Aetna Pharmacy Management refers to an internal business unit of Aetna Health Management, LLC. Aetna Pharmacy Management administers, but does not offer, insure or otherwise underwrite the prescription drug benefits portion of your health plan and has no financial responsibility therefor. 2020 Pharmacy Drug Guide - Aetna Standard Plan Table of Contents INFORMATIONAL SECTION..................................................................................................................6 *ADHD/ANTI-NARCOLEPSY/ANTI-OBESITY/ANOREXIANTS* - DRUGS FOR THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.................................................................................................................................16 *ALLERGENIC EXTRACTS/BIOLOGICALS MISC* - BIOLOGICAL AGENTS...............................18 *ALTERNATIVE MEDICINES* - VITAMINS AND MINERALS....................................................... 19 *AMEBICIDES* - DRUGS FOR INFECTIONS.....................................................................................19 *AMINOGLYCOSIDES* - DRUGS FOR INFECTIONS.......................................................................19 *ANALGESICS - ANTI-INFLAMMATORY* - DRUGS FOR PAIN AND FEVER............................19 *ANALGESICS - NONNARCOTIC* - DRUGS FOR PAIN AND FEVER......................................... -

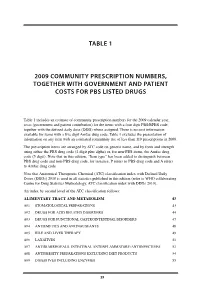

Table 1 2009 Community Prescription Numbers

TABLE 1 2009 COMMUNITY PRESCRIPTION NUMBERS, TOGETHER WITH GOVERNMENT AND PATIENT COSTS FOR PBS LISTED DRUGS Table 1 includes an estimate of community prescription numbers for the 2009 calendar year, costs (government and patient contribution) for the items with a four digit PBS/RPBS code, together with the defined daily dose (DDD) where assigned. There is no cost information available for items with a five digit Amfac drug code. Table 1 excludes the presentation of information on any item with an estimated community use of less than 110 prescriptions in 2009. The prescription items are arranged by ATC code on generic name, and by form and strength using either the PBS drug code (4 digit plus alpha) or, for non-PBS items, the Amfac drug code (5 digit). Note that in this edition, “Item type” has been added to distinguish between PBS drug code and non-PBS drug code, for instance, P refers to PBS drug code and A refers to Amfac drug code. Note that Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification index with Defined Daily Doses (DDDs) 2010 is used in all statistics published in this edition (refer to WHO collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, ATC classification index with DDDs 2010). An index by second level of the ATC classification follows: ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 43 A01 STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS 43 A02 DRUGS FOR ACID RELATED DISORDERS 44 A03 DRUGS FOR FUNCTIONAL GASTROINTESTINAL DISORDERS 47 A04 ANTIEMETICS AND ANTINAUSEANTS 48 A05 BILE AND LIVER THERAPY 49 A06 LAXATIVES 51 A07 ANTIDIARRHOEALS, INTESTINAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY/ANTIINFECTIVES -

Unscheduled Vaginal Bleeding with Progestin-Only Contraceptive Use Rachel E

Expert Reviews ajog.org Unscheduled vaginal bleeding with progestin-only contraceptive use Rachel E. Zigler, MD; Colleen McNicholas, DO, MSCI rogestin-only methods of contra- P ception include progestin-only pills Nearly 20% of women using contraception are using progestin-only contraception, (POPs), depot-medroxyprogesterone ac- including progestin-only pills, depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate, subdermal etono- etate (DMPA), subdermal etonogestrel gestrel implants, and levonorgestrel intrauterine devices. This number will continue to (ENG) implants, and levonorgestrel grow with the increased provision of long-acting reversible contraception. Although intrauterine devices (LNG IUDs). Use of overall satisfaction among women using progestin-only contraception is high, dissatis- progestin-only methods is increasing, in faction and discontinuation may be associated with unscheduled bleeding and spotting. part because of growing popularity of The exact etiology of irregular bleeding associated with progestin-containing contra- long-acting reversible contraceptives ceptives is not completely understood, yet several mechanisms have been suggested. (LARC) but also because they are safe in Several therapies targeting these mechanisms have been evaluated with mixed results. womenwith other medical comorbidities. This paper will review the physiology and management of unscheduled bleeding with The LARC methods, including intra- progestin-containing contraceptives. uterine devices (IUDs) and implants are Key words: appealing for their ease of use, long-term irregular bleeding, long-acting reversible contraception, progestin-only protection, noncontraceptive benefits, contraception, unscheduled bleeding and relatively few contraindications. Despite the benefits, both LARC and shorter acting progestin methods can women who chose the LNG IUD, ENG method. A leading cause of unscheduled result in unscheduled bleeding and implant, or DMPA at least once during bleeding with initiation is thought to be spotting, which may lead to dissatisfac- their study participation.