A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Anii-Akpe Language Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gender and Deriflection System of Miyobe1 Ines Fiedler, Benedikt Winkhart

1 The gender and deriflection system of Miyobe1 Ines Fiedler, Benedikt Winkhart 1 Introduction 1.1 The language +small language spoken in Northern Benin and Togo in a mountainous region - number of speakers: ca. 16.250 (Eberhard et al. 2019) - name means: ‘language of the mountain people’ (Heyder, p.c.) (1) ti-yɔṕ ɛ ‘mountain’ u-yɔṕ ɛ ‘person (sg)’ pi-yɔṕ ɛ ‘person (pl)’ ku-yɔṕ ɛ ‘place of the Piyobe’ mɛ-yɔṕ ɛ ‘language of the Piyobe’ - speakers of Miyobe in Togo are at least bilingual with Kabiye (Gurunsi) (???source) – other neighboring languages are Ditammari, Nawdm and Yom (Oti-Volta), Lama and Lukpa (Gurunsi) + only scarcely documented - de Lespinay (2004): lexical and some grammatical data collected in 1962 - Eneto (2004): account on nominal morphosyntax and word formation - Lébikaza (2004): description of few aspects of the language - Rongier (1996): short grammatical description with text and word list - Pali (2011): grammatical description (PhP thesis) - Urike Heyder (SIM Benin): working on a bible translation +for our analysis we use data provided by U. Heyder (personal communication), and other taken from Rongier (1996) and Pali (2011) - Heyder describes the Miyobe spoken in Benin, Rongier and Pali the one spoken in Togo, but apparently there are no big dialectal differences 1 This presentation is based on the analysis of the Miyobe gender system undertaken in the frame of the seminar on ‘Gender in African languages’, held by Tom Güldemann in 2017. The analysis was further developed within the project ‘Nominal classification in Africa between gender and declension’ (PI: Tom Güldemann), funded by the DFG (2017-2020). -

Evaluation of Agricultural Land Resources in Benin By

Evaluation of agricultural land resources in Benin by regionalisation of the marginality index using satellite data Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades (Dr. rer. nat.) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn vorgelegt von Julia Röhrig aus Waiblingen Bonn, April 2008 Angefertigt mit der Genehmigung der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn. 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. G. Menz 2. Referent: Prof. Dr. M. Janssens Tag der Promotion: 15.07.2008 Diese Dissertation ist auf dem Hochschulschriftenserver der ULB Bonn http://hss.ulb.uni-bonn.de/diss_online elektronisch publiziert. Erscheinungsjahr: 2008 Contents 1 Introduction.................................................................................................1 1.1 Problem ................................................................................................1 1.2 Objective...............................................................................................1 1.3 Project framework of the study: the IMPETUS project...............................5 1.4 Structural composition of this study.........................................................6 2 Framework for agricultural land use in Benin ..................................................8 2.1 Location................................................................................................8 2.2 Biophysical conditions for agricultural land use .........................................8 2.2.1 -

Entwicklungsprojekte Im Ländlichen Benin Im Kontext Von Migration Und Ressourcenverknappung

Entwicklungsprojekte im ländlichen Benin im Kontext von Migration und Ressourcenverknappung Eine sozialgeographische Analyse Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Fakultät für Biologie, Chemie und Geowissenschaften der Universität Bayreuth vorgelegt von Uwe Singer, Diplom-Geograph aus Köln, Bayreuth 2005 Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde in der Zeit von September 2000 bis Oktober 2005 unter der Leitung von Herrn Prof. Dr. Müller-Mahn am Lehrstuhl für Bevölkerungs- und Sozialgeographie der Universität Bayreuth angefertigt. Promotionsgesuch eingereicht am: 14.10.2005 Zulassung durch die Promotionskommission: 26.10.2005 Wissenschaftliches Kolloquium: 09.02.2006 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Dr. Carl Beierkuhnlein Prüfungsausschuß: Prof. Dr. Detlef Müller-Mahn (Erstgutachter) Prof. Dr. Beate Lohnert (Zweitgutachter) Prof. Dr. Herbert Popp (Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Dieter Neubert Prof. Dr. Wolfgang Zech Danksagung Am Entstehungsprozess der vorliegenden Arbeit waren in Benin und in Deutschland viele Personen beteiligt, denen ich im Folgenden meinen herzlichen Dank für ihr Engagement aussprechen möchte. - An erster Stelle danke ich den gastfreundlichen Menschen in den Gemeinden N’Dali und Tchaourou, die mir Einblicke in ihre wirtschaftlichen Verhältnisse und ihr Privatleben, sowie die politischen Verhältnisse des dörflichen Kontextes gestatteten. - Ein ebenbürtiger Dank gilt in Benin allen Mitarbeiter von Entwicklungsprojekten, Nichtregierungsorganisationen, privaten Entwicklungsagenturen und staatlichen Behörden, die durch ihre Auskunftsbereitschaft -

En Téléchargeant Ce Document, Vous Souscrivez Aux Conditions D’Utilisation Du Fonds Gregory-Piché

En téléchargeant ce document, vous souscrivez aux conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché. Les fichiers disponibles au Fonds Gregory-Piché ont été numérisés à partir de documents imprimés et de microfiches dont la qualité d’impression et l’état de conservation sont très variables. Les fichiers sont fournis à l’état brut et aucune garantie quant à la validité ou la complétude des informations qu’ils contiennent n’est offerte. En diffusant gratuitement ces documents, dont la grande majorité sont quasi introuvables dans une forme autre que le format numérique suggéré ici, le Fonds Gregory-Piché souhaite rendre service à la communauté des scientifiques intéressés aux questions démographiques des pays de la Francophonie, principalement des pays africains et ce, en évitant, autant que possible, de porter préjudice aux droits patrimoniaux des auteurs. Nous recommandons fortement aux usagers de citer adéquatement les ouvrages diffusés via le fonds documentaire numérique Gregory- Piché, en rendant crédit, en tout premier lieu, aux auteurs des documents. Pour référencer ce document, veuillez simplement utiliser la notice bibliographique standard du document original. Les opinions exprimées par les auteurs n’engagent que ceux-ci et ne représentent pas nécessairement les opinions de l’ODSEF. La liste des pays, ainsi que les intitulés retenus pour chacun d'eux, n'implique l'expression d'aucune opinion de la part de l’ODSEF quant au statut de ces pays et territoires ni quant à leurs frontières. Ce fichier a été produit par l’équipe des projets numériques de la Bibliothèque de l’Université Laval. Le contenu des documents, l’organisation du mode de diffusion et les conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché peuvent être modifiés sans préavis. -

Rapport ADANDE Kiv Yémalin.Pdf

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN *-*-*-* MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE *-*-*-* UNIVERSITE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI *-*-*-* ECOLE POLYTECHNIQUE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI *-*-*-* Département du Génie Civil OPTION : SCIENCE ET TECHNIQUE DE L’EAU POUR L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE LA LICENCE PROFESSIONNELLE THEME CARACTERISATION PHYSICO -CHIMIQUE DES EAUX SOUTERRAINES : CAS DE LA COMMUNE DE BASSILA Présenté par : Kiv Yémalin ADANDE Sous la supervision de : Dr. Léonce F. DOVONON Maître Assistant des Universités (CAMES), Enseignant chercheur EPAC/UAC Directeur de l’information sur l’Eau/DG Eau Année universitaire 2012-2013 CARACTERISATION PHYSICO-CHIMIQUE DES EAUX SOUTERRAINE : CAS DE LA COMMUNE DE BASSILA DEDICACE Je dédie cette œuvre à mes chers parents: Urbain V. ADANDE, et Rachelle KLE Merci pour tous les sacrifices que vous avez consentis pour moi tout au long de mon cursus scolaire. Puissiez-vous trouvez à travers cette œuvre l’expression de ma profonde gratitude. Présenté et soutenu par ADANDE Y. Kiv UAC/EPAC i CARACTERISATION PHYSICO-CHIMIQUE DES EAUX SOUTERRAINE : CAS DE LA COMMUNE DE BASSILA REMERCIEMENTS Tous mes sincères remerciements à l’endroit : Du Dieu Tout Puissant, pour toutes ses grâces et son assistance tout au long de la rédaction de ce rapport ; Du Professeur Félicien AVLESSI, Professeur Titulaire des Universités du CAMES, Enseignant-Chercheur à l’EPAC, Directeur de l’EPAC, qui a bien voulu nous ouvrir les portes de son école pour nos trois années de formation ; Du Professeur Martin P. AÏNA, Maître de Conférence des universités du CAMES, Enseignant chercheur à l’EPAC; Chef du département de Génie Civil Du Professeur Gérard GBAGUIDI AÏSSE, Maître Conférences des Universités, Enseignant chercheur à l’EPAC ; Du Professeur Edmond ADJOVI, Maître Conférence des Universités, Enseignant chercheur à l’EPAC ; Du Professeur François de Paule CODO, Maître de Conférence des Universités du CAMES, Enseignant à l’EPAC ; Chef Option Science et Techniques de l’Eau (STE) ; Du Professeur Victor S. -

Transferability, Development of Single Sequence Repeat (SSR) Markers and Application

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.30.926626; this version posted January 30, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Transferability, development of Single Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers and application 2 to the analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of the African fan palm 3 (Borassus aethiopum Mart.) in Benin 4 5 Mariano Joly Kpaténon1,2,3, Valère Kolawolé Salako2,4, Sylvain Santoni5, Leila Zekraoui3, 6 Muriel Latreille5, Christine Tollon-Cordet5, Cédric Mariac3, Estelle Jaligot 3,6 #, Thierry Beulé 7 3,6 #, Kifouli Adéoti 1,2 #* 8 9 Affiliations : 10 1 Laboratoire de Microbiologie et de Technologie Alimentaire (LAMITA), Faculté des Sciences 11 et Techniques, Université d'Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Bénin 12 2 Biodiversité et Ecologie des Plantes (BDEP), Faculté des Sciences et Techniques, Université 13 d'Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Bénin 14 3 DIADE, Univ Montpellier, IRD, Montpellier, France, 15 4 Laboratoire de Biomathématiques et d'Estimations Forestières (LABEF), Faculté des Sciences 16 Agronomiques, Université d'Abomey-Calavi, Cotonou, Bénin 17 5 AGAP, Univ Montpellier, CIRAD, INRAE, Montpellier SupAgro, Montpellier, France 18 6 CIRAD, UMR DIADE, Montpellier, France 19 20 # equal contribution as last authors 21 * corresponding author 22 Email: [email protected] (KA) 23 24 Author contributions 25 Conceptualization: VKS, EJ, TB, KA 26 Funding acquisition: VKS, EJ, TB, KA 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.30.926626; this version posted January 30, 2020. -

Plan Directeur D'electrification Hors Réseau

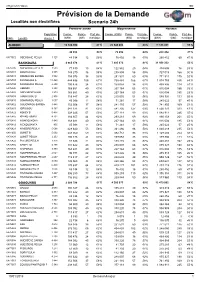

Plan Directeur d’Electrification Hors Réseau Prévision de la demande - 2018 Annexe 3 Etude pour la mise en place d’un environnement propice à l’électrification hors-réseau Présenté par : Projet : Accès à l’Électricité Hors Réseau Activité : Etude pour la mise en place d’un environnement propice à l’électrification hors-réseau Contrat n° : PP1-CIF-OGEAP-01 Client : Millennium Challenge Account-Bénin II (MCA-Bénin II) Financement : Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Gabriel DEGBEGNI - Coordonnateur National (CN) Dossier suivi par : Joel AKOWANOU - Directeur des Opérations (DO) Marcel FLAN - Chef du Projet Energie Décentralisée (CPED) Groupement : IED - Innovation Energie Développement (Fr) PAC - Practical Action Consulting Ltd (U.K) 2 chemin de la Chauderaie, 69340 Francheville, France Consultant : Tel: +33 (0)4 72 59 13 20 / Fax: +33 (0)4 72 59 13 39 E-mail : [email protected] / [email protected] Site web: www.ied-sa.fr Référence IED : 2016/019/Off Grid Bénin MCC Date de démarrage : 21 nov. 2016 Durée : 18 mois Rédaction du document : Version Note de cadrage Version 1 Version 2 FINAL Date 26 juin 2017 14 juillet 2017 07 septembre 2017 17 juin 2017 Rédaction Jean-Paul LAUDE, Romain FRANDJI, Ranie RAMBAUD Jean-Paul LAUDE - Chef de projet résident Relecture et validation Denis RAMBAUD-MEASSON - Directeur de projet Off-grid 2017 Bénin IED Prévision de la Demande Localités non électrifiées Scenario 24h Première année Moyen-terme Horizon Population Conso. Pointe Part do- Conso. (kWh) Pointe Part do- Conso. Pointe Part do- Code Localité -

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names

Appendix 1 Vernacular Names The vernacular names listed below have been collected from the literature. Few have phonetic spellings. Spelling is not helped by the difficulties of transcribing unwritten languages into European syllables and Roman script. Some languages have several names for the same species. Further complications arise from the various dialects and corruptions within a language, and use of names borrowed from other languages. Where the people are bilingual the person recording the name may fail to check which language it comes from. For example, in northern Sahel where Arabic is the lingua franca, the recorded names, supposedly Arabic, include a number from local languages. Sometimes the same name may be used for several species. For example, kiri is the Susu name for both Adansonia digitata and Drypetes afzelii. There is nothing unusual about such complications. For example, Grigson (1955) cites 52 English synonyms for the common dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) in the British Isles, and also mentions several examples of the same vernacular name applying to different species. Even Theophrastus in c. 300 BC complained that there were three plants called strykhnos, which were edible, soporific or hallucinogenic (Hort 1916). Languages and history are linked and it is hoped that understanding how lan- guages spread will lead to the discovery of the historical origins of some of the vernacular names for the baobab. The classification followed here is that of Gordon (2005) updated and edited by Blench (2005, personal communication). Alternative family names are shown in square brackets, dialects in parenthesis. Superscript Arabic numbers refer to references to the vernacular names; Roman numbers refer to further information in Section 4. -

Farmers' Perceptions of Climate Change and Farm-Level Adaptation

African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics Volume 14 Number 1 pages 42-55 Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and farm-level adaptation strategies: Evidence from Bassila in Benin Achille A. Diendere Department of Economics and Management, University Ouaga II, Burkina Faso. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Very few studies of the agricultural sector’s adaptation to climate change have been conducted in Benin. This paper focuses on farmers’ perceptions and adaptation decisions in relation to climate change. A double hurdle model that includes a logit regression and a truncated negative binomial regression was developed using data from a survey of 200 farmers located in northern Benin. The results show that farmers’ perceptions of climate change support the macro-level evidence. The econometric results reveal that the most effective ways to increase the probability of adaptation are to secure land rights and support the creation and strengthening of local farm organisations. The most effective ways to increase the intensity of adaptation are to improve access to agricultural finances and extension. The findings of this study have several public policy implications for creating an enabling environment for adaptation to climate change in Benin. Keys words: decision to adapt; intensity of adaptation; climate change; double hurdle model; Benin. 1. Introduction Climate change has had a significant affect on the pattern of precipitation and has caused frequent extreme weather events, leading to natural disasters such as droughts and floods (IPCC 2007, 2014a; Schlenker & Lobell 2010). Benin’s crop production and food security are beginning to be threatened by climate change (Gnanglé et al. -

Prйvision De La Demande

Off-grid 2017 Bénin IED Prévision de la Demande Localités non électrifiées Scenario 24h Première année Moyen-terme Horizon Population Conso. Pointe Part do- Conso. (kWh) Pointe Part do- Conso. Pointe Part do- Code Localité Année 1 (kWh) (kW) mestique (kW) mestique (kWh) (kW) mestique ALIBORI 16 384 994 61% 26 548 492 60% 77 186 801 55 % 48 334 59% 76 492 60% 260 452 47% 6877072 GBESSARE PEULH 28 517,06 1 125 48 334 12 45 895,2059% 76 492 18 122 412,4460% 260 452 60 47 % BANIKOARA 4 665 376 61% 7 485 672 61% 21 936 332 55% 6876796 BOFOUNOU-PEULH 42 028,20 1 593 77 830 19 66 194,2854% 122 582 29 177 341,1854% 334 606 76 53 % 6876807 BOUHANROU 86 576,60 3 335 149 270 36 136 821,4258% 235 899 56 363 509,5058% 727 019 166 50 % 6876813 DOMBOURE BARIBA 93 795,84 3 582 158 976 38 150 918,6059% 251 531 60 401 185,7260% 771 511 175 52 % 6876797 FOUNOUGO A 298 080,32 11 420 444 896 105 474 683,6167% 708 483 166 1 263 845,7667% 1 974 759 435 64 % 6876799 FOUNOUGO PEULH 60 285,60 2 290 100 476 24 95 434,8060% 159 058 38 254 901,0660% 499 806 114 51 % 6876840 GBENIKI 101 208,60 3 858 168 681 40 162 970,0460% 267 164 63 432 482,1261% 816 004 185 53 % 6876800 GNINGNIMPOGOU 101 208,60 3 919 168 681 40 162 970,0460% 267 164 63 432 482,1261% 816 004 185 53 % 6876809 GOMPAROU B 75 528,81 2 908 119 887 28 120 430,8063% 215 055 51 323 835,0556% 588 791 133 55 % 6876810 GOMPAROU PEULH 26 156,84 1 037 45 098 11 41 342,9858% 71 281 17 110 529,9058% 245 622 57 45 % 6876802 GOUGNIROU-BARIBA 88 453,48 3 446 152 506 37 142 254,9058% 241 110 57 378 343,5059% 741 850 -

Dagbani-English Dictionary

DAGBANI-ENGLISH DICTIONARY with contributions by: Harold Blair Tamakloe Harold Lehmann Lee Shin Chul André Wilson Maurice Pageault Knut Olawski Tony Naden Roger Blench CIRCULATION DRAFT ONLY ALL COMENTS AND CORRECTIONS WELCOME This version prepared by; Roger Blench 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm This printout: Tamale 25 December, 2004 1. Introduction...................................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Transcription.................................................................................................................................................... 5 Vowels ................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Consonants......................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Tones .................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Plurals and other forms.................................................................................................................................................... 8 Variability in Dagbani -

Sewell 1..277

VU Research Portal Calvin and the Body Sewell, A.L. 2011 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Sewell, A. L. (2011). Calvin and the Body: An Inquiry into His Anthropology. VU University Press. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Acknowledgements Theologians of the twelfth century liked to say that we can see a little further because we sit on the shoulders of giants. I, too, have benefited from the labors of Calvin scholars near and far. Any Calvin scholar today owes a debt of gratitude to those who have gone before. I gratefully acknowledge the hospitality of various libraries and their staff. In my current hometown of Sioux Center, IA, I was able to use the John and Louise Hulst Library at Dordt College.