The Dialects of Anii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carte Pédologique De Reconnaissance De La République Populaire Du Bénin À 1/200.000 : Feuille De Djougou

P. FAURE NOTICE EXPLICATIVE No 66 (4) CARTE PEDOLOGIQUE DE RECONNAISSANCE de la République Populaire du Bénin à 1/200.000 Feuille de DJOUGOU OFFICE OE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIWE ET TECHNIOUE OUTRE-MER 1 PARIS 1977 NOTICE EXPLICATIVE No 66 (4) CARTE PEDOLOGIQUE DE RECONNAISSANCE de la RepubliquePopulaire du Bénin à 1 /200.000 Feuille de DJOUGOU P. FAURE ORSTOM PARIS 1977 @ORSTOM 2977 ISBN 2-7099-0423-3(édition cornpl8te) ISBN 2-7099-0433-0 SOMMAI RE l. l INTRODUCTION ........................................ 1 I .GENERALITES SUR LE MILIEU ET LA PEDOGENESE ........... 3 Localisationgéographique ............................ 3 Les conditionsde milieu 1. Le climat ................... 3 2 . La végétation ................. 6 3 . Le modelé et l'hydrographie ....... 8 4 . Le substratum géologique ........ 10 Les matériaux originels et la pédogenèse .................. 12 1 . Les matériaux originels .......... 12 2 . Les processus pédogénétiques ...... 13 II-LESSOLS .......................................... 17 Classification 1. Principes de classification ....... 17 2 . La légende .................. 18 Etudemonographique 1 . Les sols minérauxbruts ......... 20 2 . Les sois peuévolués ............ 21 3 . Les sols ferrugineuxtropicaux ....... 21 4 . Les sols ferraliitiques ........... 38 CONCLUSION .......................................... 43 Répartitiondes' sols . Importance relative . Critèresd'utilisation . 43 Les principalescontraintes pour la mise en valeur ............ 46 BIBLIOGRAPHIE ........................................ 49 1 INTRODUCTION La carte pédologique de reconnaissance à 1/200 000, feuille DJOUGOU, fait partie d'un ensemble de neuf coupures imprimées couvrant la totalité du terri- toire de la République Populaire du Bénin. Les travaux de terrain de la couverture générale ont été effectués de 1967 à 1971 par les quatre pédologues de la Section de Pédologie du Centre O. R.S. T.O.M. de Cotonou : D. DUBROEUCQ, P. FAURE, M. VIENNOT, B. -

En Téléchargeant Ce Document, Vous Souscrivez Aux Conditions D’Utilisation Du Fonds Gregory-Piché

En téléchargeant ce document, vous souscrivez aux conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché. Les fichiers disponibles au Fonds Gregory-Piché ont été numérisés à partir de documents imprimés et de microfiches dont la qualité d’impression et l’état de conservation sont très variables. Les fichiers sont fournis à l’état brut et aucune garantie quant à la validité ou la complétude des informations qu’ils contiennent n’est offerte. En diffusant gratuitement ces documents, dont la grande majorité sont quasi introuvables dans une forme autre que le format numérique suggéré ici, le Fonds Gregory-Piché souhaite rendre service à la communauté des scientifiques intéressés aux questions démographiques des pays de la Francophonie, principalement des pays africains et ce, en évitant, autant que possible, de porter préjudice aux droits patrimoniaux des auteurs. Nous recommandons fortement aux usagers de citer adéquatement les ouvrages diffusés via le fonds documentaire numérique Gregory- Piché, en rendant crédit, en tout premier lieu, aux auteurs des documents. Pour référencer ce document, veuillez simplement utiliser la notice bibliographique standard du document original. Les opinions exprimées par les auteurs n’engagent que ceux-ci et ne représentent pas nécessairement les opinions de l’ODSEF. La liste des pays, ainsi que les intitulés retenus pour chacun d'eux, n'implique l'expression d'aucune opinion de la part de l’ODSEF quant au statut de ces pays et territoires ni quant à leurs frontières. Ce fichier a été produit par l’équipe des projets numériques de la Bibliothèque de l’Université Laval. Le contenu des documents, l’organisation du mode de diffusion et les conditions d’utilisation du Fonds Gregory-Piché peuvent être modifiés sans préavis. -

Influence Des Pressions Anthropiques Sur La Structure Des Populations De Pentadesma Butyracea Au Bénin

Document generated on 09/28/2021 1:27 a.m. VertigO La revue électronique en sciences de l’environnement Influence des pressions anthropiques sur la structure des populations de Pentadesma butyracea au Bénin Influence of human activities on Pentadesma butyracea populations structure in Benin Aliou Dicko, Samadori Sorotori Honoré Biaou, Armand Kuyema Natta, Choukouratou Aboudou Salami Gado and M’Mouyohoum Kouagou Vulnérabilités environnementales : perspectives historiques Article abstract Volume 16, Number 3, December 2016 The present study examined the influence of human activities on the structural characteristics of the populations of P. butyracea, a vulnerable multipurpose URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1039997ar woody species. A total of 116 plots of 500 m² were randomly installed, 68 in the sudanian region and 48 in the sudano-guinean region, for dendrometric and See table of contents floristic inventories. The populations of P. butyracea were categorized according to human pressures they are exposed to, using a Factorial Analysis of Correspondences. Three groups were discriminated : Group 1 (populations of Penessoulou and Kandi), characterized by a pressure from wild vegetation Publisher(s) fires and agricultural activities ; Group 2 (populations of Manigri and Ségbana), Université du Québec à Montréal characterized by illegal selective logging, abusive barking of P. butyracea, Éditions en environnement VertigO animal grazing ; and Group 3 (populations of Natitingou, Toucountouna and Tchaourou), characterized by excessive seeds collection and sand removal from the stream by humans. The diameter distribution structures were of left ISSN or right dissymmetry according to pressures types to which the discriminated 1492-8442 (digital) groups are subjected. For a conservation of remnant populations of P. -

Rapport ADANDE Kiv Yémalin.Pdf

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN *-*-*-* MINISTERE DE L’ENSEIGNEMENT SUPERIEUR ET DE LA RECHERCHE SCIENTIFIQUE *-*-*-* UNIVERSITE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI *-*-*-* ECOLE POLYTECHNIQUE D’ABOMEY-CALAVI *-*-*-* Département du Génie Civil OPTION : SCIENCE ET TECHNIQUE DE L’EAU POUR L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE LA LICENCE PROFESSIONNELLE THEME CARACTERISATION PHYSICO -CHIMIQUE DES EAUX SOUTERRAINES : CAS DE LA COMMUNE DE BASSILA Présenté par : Kiv Yémalin ADANDE Sous la supervision de : Dr. Léonce F. DOVONON Maître Assistant des Universités (CAMES), Enseignant chercheur EPAC/UAC Directeur de l’information sur l’Eau/DG Eau Année universitaire 2012-2013 CARACTERISATION PHYSICO-CHIMIQUE DES EAUX SOUTERRAINE : CAS DE LA COMMUNE DE BASSILA DEDICACE Je dédie cette œuvre à mes chers parents: Urbain V. ADANDE, et Rachelle KLE Merci pour tous les sacrifices que vous avez consentis pour moi tout au long de mon cursus scolaire. Puissiez-vous trouvez à travers cette œuvre l’expression de ma profonde gratitude. Présenté et soutenu par ADANDE Y. Kiv UAC/EPAC i CARACTERISATION PHYSICO-CHIMIQUE DES EAUX SOUTERRAINE : CAS DE LA COMMUNE DE BASSILA REMERCIEMENTS Tous mes sincères remerciements à l’endroit : Du Dieu Tout Puissant, pour toutes ses grâces et son assistance tout au long de la rédaction de ce rapport ; Du Professeur Félicien AVLESSI, Professeur Titulaire des Universités du CAMES, Enseignant-Chercheur à l’EPAC, Directeur de l’EPAC, qui a bien voulu nous ouvrir les portes de son école pour nos trois années de formation ; Du Professeur Martin P. AÏNA, Maître de Conférence des universités du CAMES, Enseignant chercheur à l’EPAC; Chef du département de Génie Civil Du Professeur Gérard GBAGUIDI AÏSSE, Maître Conférences des Universités, Enseignant chercheur à l’EPAC ; Du Professeur Edmond ADJOVI, Maître Conférence des Universités, Enseignant chercheur à l’EPAC ; Du Professeur François de Paule CODO, Maître de Conférence des Universités du CAMES, Enseignant à l’EPAC ; Chef Option Science et Techniques de l’Eau (STE) ; Du Professeur Victor S. -

Plan Directeur D'electrification Hors Réseau

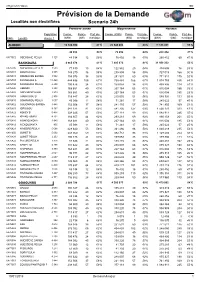

Plan Directeur d’Electrification Hors Réseau Prévision de la demande - 2018 Annexe 3 Etude pour la mise en place d’un environnement propice à l’électrification hors-réseau Présenté par : Projet : Accès à l’Électricité Hors Réseau Activité : Etude pour la mise en place d’un environnement propice à l’électrification hors-réseau Contrat n° : PP1-CIF-OGEAP-01 Client : Millennium Challenge Account-Bénin II (MCA-Bénin II) Financement : Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) Gabriel DEGBEGNI - Coordonnateur National (CN) Dossier suivi par : Joel AKOWANOU - Directeur des Opérations (DO) Marcel FLAN - Chef du Projet Energie Décentralisée (CPED) Groupement : IED - Innovation Energie Développement (Fr) PAC - Practical Action Consulting Ltd (U.K) 2 chemin de la Chauderaie, 69340 Francheville, France Consultant : Tel: +33 (0)4 72 59 13 20 / Fax: +33 (0)4 72 59 13 39 E-mail : [email protected] / [email protected] Site web: www.ied-sa.fr Référence IED : 2016/019/Off Grid Bénin MCC Date de démarrage : 21 nov. 2016 Durée : 18 mois Rédaction du document : Version Note de cadrage Version 1 Version 2 FINAL Date 26 juin 2017 14 juillet 2017 07 septembre 2017 17 juin 2017 Rédaction Jean-Paul LAUDE, Romain FRANDJI, Ranie RAMBAUD Jean-Paul LAUDE - Chef de projet résident Relecture et validation Denis RAMBAUD-MEASSON - Directeur de projet Off-grid 2017 Bénin IED Prévision de la Demande Localités non électrifiées Scenario 24h Première année Moyen-terme Horizon Population Conso. Pointe Part do- Conso. (kWh) Pointe Part do- Conso. Pointe Part do- Code Localité -

Zwischenbericht 2006

IMPETUS Westafrika Integratives Management-Projekt für einen Effizienten und Tragfähigen Umgang mit Süßwasser in Westafrika: Fallstudien für ausgewählte Flusseinzugsgebiete in unterschiedlichen Klimazonen Siebter Zwischenbericht Zeitraum: 1.1.2006 - 31.12.2006 Ein interdisziplinäres Projekt der Universität zu Köln und der Universität Bonn 01. April 2007 IMPETUS Koordinierende Institutionen Universität zu Köln Universität Bonn Institut für Geophysik und Meteorologie Geologisches Institut HD. Dr. habil A. Fink (Sprecher) Prof. Dr. B. Reichert (Stellv. Sprecher) Kerpener Str. 13 Nussallee 166 D-50923 Köln D-53115 Bonn Tel.: 0221-470 3819 / Fax: 0221-470 5161 Tel.: 0228-73 2490 / Fax: 0228-73 9037 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Kontaktadresse: Universität zu Köln Institut für Geophysik und Meteorologie Dr. M. Christoph (Geschäftsführer) Kerpener Straße 13 D – 50923 Köln Telephon: (0221) 470 3690 Fax: (0221) 470 5161 E-mail: [email protected] IMPETUS Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite I Zusammenfassung 1 II Spatial Decision Support Systems (SDDS) 7 II.1 Entwicklung des IMPETUS SDSS Frameworks 7 II.2 Entwicklung der SDSS 11 II.3 Datenbanken 18 II.4 Internet 19 III Stand der Problemkomplexe 23 III.1 Benin und seine Themenbereiche 23 III.1.1 Ernährungssicherung 23 PK Be-E.1 Landnutzung und Versorgungssicherung bei Ressourcenknappheit und Niederschlagsvariabilität in Benin 23 PK Be-E.2 Auswirkungen von Landnutzungsänderungen, Klimaveränderungen und Pflanzenmanagement auf Bodendegradation und Ernteertrag im oberen -

Farmers' Perceptions of Climate Change and Farm-Level Adaptation

African Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics Volume 14 Number 1 pages 42-55 Farmers’ perceptions of climate change and farm-level adaptation strategies: Evidence from Bassila in Benin Achille A. Diendere Department of Economics and Management, University Ouaga II, Burkina Faso. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Very few studies of the agricultural sector’s adaptation to climate change have been conducted in Benin. This paper focuses on farmers’ perceptions and adaptation decisions in relation to climate change. A double hurdle model that includes a logit regression and a truncated negative binomial regression was developed using data from a survey of 200 farmers located in northern Benin. The results show that farmers’ perceptions of climate change support the macro-level evidence. The econometric results reveal that the most effective ways to increase the probability of adaptation are to secure land rights and support the creation and strengthening of local farm organisations. The most effective ways to increase the intensity of adaptation are to improve access to agricultural finances and extension. The findings of this study have several public policy implications for creating an enabling environment for adaptation to climate change in Benin. Keys words: decision to adapt; intensity of adaptation; climate change; double hurdle model; Benin. 1. Introduction Climate change has had a significant affect on the pattern of precipitation and has caused frequent extreme weather events, leading to natural disasters such as droughts and floods (IPCC 2007, 2014a; Schlenker & Lobell 2010). Benin’s crop production and food security are beginning to be threatened by climate change (Gnanglé et al. -

Liste Des Centres De Vote Code Vq Village Quartier

REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN -------------- CONSEIL D’ORIENTATION ET DE SUPERVISION -------------- CENTRE NATIONAL DE TRAITEMENT ------------- LISTE DES CENTRES DE VOTE 1. DEPARTEMENT : ALIBORI 2. COMMUNE : BANIKOARA 3. ARRONDISSEMENT : FOUNOUGO 4. CODE DE L’ARRONDISSEMENT : 010101 CODE_VQ VILLAGE_QUARTIER CODE_CV CENTRE DE VOTE 0101010101 CENTRE ALPHAB. BOFOUNNOU 01010101 BOFOUNOU 0101010102 EPP BANDEGOU 0101010201 CEG FOUNOUGO 0101010202 CEG GANSSINSSON 0101010203 EPP BANTE 01010102 FOUNOUGO-BOUTERA 0101010204 EPP GBEDODOU 0101010205 EPP GOSSIRA 0101010206 EPP TOROMA 0101010207 MAISON DES JEUNES 0101010301 MAGASIN GVPC GLOWE 01010103 FOUNOUGO-GAH 0101010302 MAISON DES JEUNES 0101010401 BUREAU ARONDISSEMENT 0101010402 EM FOUNOUGO 0101010403 EPP BANFANNOU 01010104 FOUNOUGO-GOROBANI 0101010404 EPP FOUNOUGO G/B 0101010405 MAGASIN GV GANOUSSINROU 0101010406 MAGASIN GV GANSSINSSON YABADOU 0101010407 MAGASIN GV YABADOU 0101010501 EPP DARE G/A ET B 0101010502 EPP GAMA 01010105 GAMA 0101010503 EPP YABAKPIGOU 0101010504 MAGASIN GV YINKOGA 0101010601 EPP GAMARE ZONGO 01010106 GAMERE-ZONGO 0101010602 MAGASIN GV BOGNANNI 0101010701 EPP GOUGNIROU 01010107 GOUGNIROU 0101010702 MAGASIN GAMARE ZONGO 01010108 GOUGNIROU-GAH 0101010801 CENTRE D’ALPHABETISATION 0101010901 EPP IBOTO 01010109 IBOTO 0101010902 MAGASIN GV BONTINNA 01010110 IGRIGOU 0101011001 EPP IGRIGOU 01010111 KANDEROU 0101011101 EPP KANDEROU 0101011102 EPP WOGOBIGA 0101011103 EPP YABADOU 0101011201 EPP KANDEROU KOTCHERA 01010112 KANDEROU-KOTCHERA 0101011202 EPP NIPOUNI 0101011203 MAGASIN GV DOGO -

Prйvision De La Demande

Off-grid 2017 Bénin IED Prévision de la Demande Localités non électrifiées Scenario 24h Première année Moyen-terme Horizon Population Conso. Pointe Part do- Conso. (kWh) Pointe Part do- Conso. Pointe Part do- Code Localité Année 1 (kWh) (kW) mestique (kW) mestique (kWh) (kW) mestique ALIBORI 16 384 994 61% 26 548 492 60% 77 186 801 55 % 48 334 59% 76 492 60% 260 452 47% 6877072 GBESSARE PEULH 28 517,06 1 125 48 334 12 45 895,2059% 76 492 18 122 412,4460% 260 452 60 47 % BANIKOARA 4 665 376 61% 7 485 672 61% 21 936 332 55% 6876796 BOFOUNOU-PEULH 42 028,20 1 593 77 830 19 66 194,2854% 122 582 29 177 341,1854% 334 606 76 53 % 6876807 BOUHANROU 86 576,60 3 335 149 270 36 136 821,4258% 235 899 56 363 509,5058% 727 019 166 50 % 6876813 DOMBOURE BARIBA 93 795,84 3 582 158 976 38 150 918,6059% 251 531 60 401 185,7260% 771 511 175 52 % 6876797 FOUNOUGO A 298 080,32 11 420 444 896 105 474 683,6167% 708 483 166 1 263 845,7667% 1 974 759 435 64 % 6876799 FOUNOUGO PEULH 60 285,60 2 290 100 476 24 95 434,8060% 159 058 38 254 901,0660% 499 806 114 51 % 6876840 GBENIKI 101 208,60 3 858 168 681 40 162 970,0460% 267 164 63 432 482,1261% 816 004 185 53 % 6876800 GNINGNIMPOGOU 101 208,60 3 919 168 681 40 162 970,0460% 267 164 63 432 482,1261% 816 004 185 53 % 6876809 GOMPAROU B 75 528,81 2 908 119 887 28 120 430,8063% 215 055 51 323 835,0556% 588 791 133 55 % 6876810 GOMPAROU PEULH 26 156,84 1 037 45 098 11 41 342,9858% 71 281 17 110 529,9058% 245 622 57 45 % 6876802 GOUGNIROU-BARIBA 88 453,48 3 446 152 506 37 142 254,9058% 241 110 57 378 343,5059% 741 850 -

A. K. Natta*, H. Yédomonhan**, N. Zoumarou-Wallis*, J

Annales des Sciences Agronomiques 15 (2) : 137-152, 2011 ISSN 1659-5009 TYPOLOGIE ET STRUCTURE DES POPULATIONS NATURELLES DE PENTADESMA BUTYRACEA DANS LA ZONE SOUDANOSOUDANO----GUINGUINGUINÉÉÉÉENNEENNE DU BBÉÉÉÉNINNINNINNIN A. K. NATTA*, H. YÉDOMONHAN**, N. ZOUMAROU-WALLIS*, J. HOUNDEHIN*, E. B. K. ÉWÉDJÈ ** & R. L. GLÈLÈ KAKAÏ*** *Dep./AGRN, Faculté d’Agronomie (FA), Université de Parakou. BP 123 Parakou, Bénin ; Email : [email protected] **Laboratoire de Botanique et d’Ecologie Végétale, Faculté des Sciences et Techniques (FAST), Université d’Abomey Calavi. 01 BP 4521 Cotonou, Bénin ; ***Département d’Aménagement et de Gestion de l’Environnement, Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques (FSA), Université d’Abomey Calavi. 01 BP 526 Cotonou, Bénin. RRRÉRÉÉÉSUMSUMSUMSUMÉÉÉÉ La présente étude, conduite dans la région soudano-guinéenne du centre Bénin, a pour objectif la caractérisation écologique de Pentadesma butyracea, une espèce vulnérable au Bénin, à travers l’inventaire, la typologie et la caractérisation structurale de ses populations naturelles. Les inventaires floristiques et dendrométriques ont été faits dans cent placeaux de 500 m2, de longueur et largueur variables, dans tous les sites de forêts galeries à dominance P. butyracea . Les données collectées sont l’abondance, la richesse spécifique, la densité, la surface terrière, l’Indice Shannon et l’équitabilité de Pielou. Dans la région soudano-guinéenne du Centre Bénin, P. butyracea est présent dans 76 sites avec une abondance de 1.132 individus adultes (dbh ≥ 10 cm). Sur la base des caractéristiques écologiques des sites, cinq populations de P. butyracea ont été identifiées. Il s’agit des populations de Bassila, Koura, Manigri, Pénéssoulou et Agbassa, qui sont différentes sur le plan statistique pour chacun des paramètres écologiques à savoir la densité, la surface terrière, la richesse spécifique, l’Indice de Shannon et l’Equitabilité de Pielou (Prob. -

Ghana Togo Benin Burkina Fasoap030

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !^ ! ! !^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! ! k! ! ! ! ! ! k ! ! !^ ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! k ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ^ ! ! ! ! ¼ ! ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! !^ ! ! ! k ! > ! k ! !^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! k k ! !^ ! ! !^ !^ ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Boulé Nioasna Kouaré !Bouamouandi ! k ! ! Sanguie Ganzourgou Kouritenga k ! ! ! Toéssé k ! Garango hau ! Bazega k Tenkodogo Komondjari Sissili ! ! !^ ! ! k ! 1 mos 1 ! ! Manga Gao ! ! ! !^ Tapoa ! ! hau k ! ! Ziro gux hau ! dje ! ! Ouargaye ! ! ! Boulgou k ! ! Zoundweogo ! dgd k bib mos ! Madjoari ! ! nnw ! !Gomboussougou ! ! ! ! Kompienga ! k ! ! dgd Zonsé Koulpelogo ! Alibori Recorded Priority #1,2, & 3 ! ! ! ! ! 2 beh beh 2 k ! Bittou ! ! Pama ! 0 xsm k ! 3 ! Languag0es of ! P ! A ! Pô Zabré ! ! Nahouri ! ! !^ ! !^ Burkina Faso ! ! p k Léo Tiébélé bib mfq Togo S ! Sissili ! bib ! !^ gur Bawku Koabagou ! > Zambéndé ! ! ! kus ! ! Nadjouni ! ! sld Jijan Wuru ! k SGmallw cityoNalutional/provincial capitals ! ! mos ! Paga !Ponio gux or population > 50,000 rank ! ! ! Lamboya ! !^ Capitals ! Firou k Bongo ! ! ! ^ ! Navrongo Warinyaga !Batia ! 3 ssl Provincial capitals xsm ! 3 !^ Kwunchogaw k Dapaong ! ! kus Garu Natinga Tami Mandouri ! Population > 500,000 ! ! k ! ! ! " ! ! ! ! S Population > 100,000 Nakong-A! tinia ! Bolgatanga > Population > 50,000 Kugri Natinga !Jeffisi Upper East !^ ! Nassoukou ! k ! Roads gur Binaba ! ! ! Boilougou ! ! beh Description ! Yakrigourou xkt !Winkogo mfq gux -

El-Nb-Recueil-De-Cartes-Bassila.Pdf

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit, GTZ, GmbH Bénin Projet Restauration des Ressources Forestières de Bassila Recueil de Cartes Janvier 2004 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit, GTZ, GmbH Bénin Projet Restauration des Ressources Forestières de Bassila Recueil de Cartes Janvier 2004 Vos partenaires A la GFA Terra Systems sont Tomas Keilbach Dr. Frank Czesnik Bénin Projet Restauration des Ressources Forestières de Bassila Recueil de Cartes Auteurs : Nazaire BOTOKOU Noe AGOSSA Holger DIEDRICH Adresse GFA Terra Systems GmbH Eulenkrugstraâe 82 22359 Hamburg Allemagne Téléphone 0049-40-60 30 6-100 Téléfax 0049-40-60 30 6-119 E-mail [email protected] Table des matières 1 Bénin 2 Commune de Bassila 3 Arrondissements 4 Terroirs 5 Forêts Classées de Bassila et de Pénéssoulou 6 Forêts privées 1 Bénin 0°15 1° 2° 3° 4° 4°30 12°25 12°25 Niger fl. Mékrou REPUBLIQUE DU BENIN N I G E R LIMITES ADMINISTRATIVES Karimama ! 12° 12° Malanville ! B U R K I N A F A S O Alibori Sota Banikoara ! D Pendjari @ KANDI 11° 11° Segbana! Gogounou ! ! Kérou Matéri ! Tanguiéta! Kobli ! ! Toukountouna Kouandé Sinendé NATITINGOU ! ! @ ! Kalalé Péhunco Bembèrèkè ! ! ! Boukoumbé 10° 10° ! Birni ! Nikki Kopargo ! ! N'dali Pèrèrè! @ DJOUGOU Ouaké! PARAKOU @ 9° ! Bassila 9° Tchaourou Alibori T O G O ! N I G E R I A Borgou Atacora Donga Collines ! Bantè Ouessè Zou ! Zou Mono Ouémé Couffo Atlantique Savè Ouèdèmè ! Littoral 8° ! 8° Savalou ! Littoral Ouémé ! Dassa Opkara Plateau Zou Réseau hydrographique Limite d'Etat Ouémé Limite de Département