The Chesapeake, a Boating Guide to Weather

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DNR Fine Schedule

JOHN P. MORRISSEY DISTRICT COURT OF MARYLAND 187 Harry S Truman Parkway, 5th Floor Chief Judge Annapolis, Maryland 21401 Tel: (410) 260-1525 Fax: (410) 260-1375 December 31, 2020 TO: All Law Enforcement Officers of the State of Maryland Authorized to Issue Citations for Violations of the Natural Resources Laws The attached list is a fine or penalty deposit schedule for certain violations of the Natural Resources laws. The amounts set out on this schedule are to be inserted by you in the appropriate space on the citation. A defendant who does not care to contest guilt may prepay the fine in that amount. The fine schedule is applicable whether the charge is made by citation, a statement of charges, or by way of criminal information. For some violations, a defendant must stand trial and is not permitted to prepay a fine or penalty deposit. Additionally, there may be some offenses for which there is no fine listed. In both cases, you should check the box which indicates that the defendant must appear in court on the offense. I understand that this fine schedule has been approved for legal sufficiency by the Office of the Attorney General, Department of Natural Resources. This schedule has, therefore, been adopted pursuant to the authority vested in the Chief Judge of the District Court by the Constitution and laws of the State of Maryland. It is effective January 1, 2021, replacing all schedules issued prior hereto, and is to remain in force and effect until amended or repealed. No law enforcement officer in the State is authorized to deviate from this schedule in any case in which they are involved. -

July 2001 FBYC Web Site

July 2001 FBYC Web Site: http://www.FBYC.net Junior Week as 16 year olds.” After the From the Quarterdeck by Strother Scott, Commodore Leukemia Cup, from C.T. Hill, CEO of One of the joys of being your Compliments I received included – our lead sponsor – “I am very happy we commodore has been being at Club for “My kid just finished the Opti-kid at SunTrust chose to become a sponsor the last 10 days and watching in program – Jan Monnier does a really of your event. This is a good event for a wonder as the Club conducts large and great job with those children – we’ll good cause with good people. SunTrust complex functions and executes them be back again.” After Junior Week is proud to be associated with it.” perfectly. We have just concluded 2 from a member – “I want you to Our hopes are high for our traveling weekends of Opti-Kids (25 children), know that this year’s Junior Week Juniors. Our Coaches, Blake the biggest and best Junior Week ever was well run, the layout at the club Kimbrough (MRBYTEMAN@aol. held (110 students, 24 instructors and worked really well in spite of no com) and Anthony Kuppersmith 6 CITs), and the 2001 Southern Bay clubhouse. My wife and I and our ([email protected]) are ready and the Volvo Leukemia Cup (53 boats racing children have had a great time, it has calendar is set (see http://www.fbyc.net/ and over $80,000 raised). The turned out to be the best vacation Juniors/). -

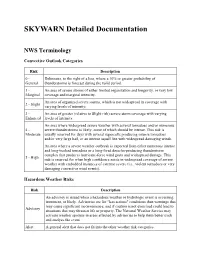

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation

SKYWARN Detailed Documentation NWS Terminology Convective Outlook Categories Risk Description 0 - Delineates, to the right of a line, where a 10% or greater probability of General thunderstorms is forecast during the valid period. 1 - An area of severe storms of either limited organization and longevity, or very low Marginal coverage and marginal intensity. An area of organized severe storms, which is not widespread in coverage with 2 - Slight varying levels of intensity. 3 - An area of greater (relative to Slight risk) severe storm coverage with varying Enhanced levels of intensity. An area where widespread severe weather with several tornadoes and/or numerous 4 - severe thunderstorms is likely, some of which should be intense. This risk is Moderate usually reserved for days with several supercells producing intense tornadoes and/or very large hail, or an intense squall line with widespread damaging winds. An area where a severe weather outbreak is expected from either numerous intense and long-tracked tornadoes or a long-lived derecho-producing thunderstorm complex that produces hurricane-force wind gusts and widespread damage. This 5 - High risk is reserved for when high confidence exists in widespread coverage of severe weather with embedded instances of extreme severe (i.e., violent tornadoes or very damaging convective wind events). Hazardous Weather Risks Risk Description An advisory is issued when a hazardous weather or hydrologic event is occurring, imminent, or likely. Advisories are for "less serious" conditions than warnings that may cause significant inconvenience, and if caution is not exercised could lead to Advisory situations that may threaten life or property. The National Weather Service may activate weather spotters in areas affected by advisories to help them better track and analyze the event. -

HOME of the FRIENDLIEST PEOPLE on the BAY 37º 12′ 20″ N 76º 26′ 11″ W August 2020 Volume #40, Number 8

HOME OF THE FRIENDLIEST PEOPLE ON THE BAY 37º 12′ 20″ N 76º 26′ 11″ W August 2020 Volume #40, Number 8 WWW.SEAFORDYACHTCLUB.COM Hello SYC! We finally got to see each other in person last month. Maybe we should have a new directory made with pictures of everyone wearing their masks. It's sometimes hard to rec- ognize someone who you haven't seen in six months especially when they are wearing a mask. I had to do a few double takes to see and figure out who I was talking to! The twice postponed Flag Raising ceremony finally happened on July 12th. Past Commodore Cecil and Barbara Adcox did a wonderful job of decorating and adapting the event to meet the new Phase 3 guidelines. I guess boating season is finally open! Our new building is finally complete. The Fire Marshall's inspection passed, final inspection with York County passed, and we have a Certificate of Occupancy! It's been a long process but well worth it. The front of our Clubhouse gives an awesome first impression as you're driving onto the Club property. Inside decorating and furnishings are coming along. Junior Sailing got off to a great start (after a two week Coronavirus delay). Thanks Paul Hutter and Red Eilenfield for another great season. Due to the large number of people anticipated and concerns about social distancing on the spectator boats, the end of the year regatta has been canceled. Well, our joyride into Phase 3 didn't last too long. Due to the limitations imposed in the Governor's latest Executive Order 68, we had to postpone the Summer Party (August 1st ) and cancel the next regular monthly dinner (August 18th.). -

Programming NOAA Weather Radio

Why Do I Need a NOAA Weather Radio? ⦿ NOAA Weather Radio is an "All Hazards" radio network, making it your single source for comprehensive weather and emergency information. ⦿ One of the quickest and most reliable way to get life saving weather and emergency alerts from government and public safety officials. ⦿ NWR is provided as a public service by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), part of the Department of Commerce. What Features Do Weather Radios Have? ⦿ Tone alarm ⦿ S.A.M.E. Technology ⦿ Selectable alerting of events ⦿ Battery backup ● In the event of a power outage the radio will still work with the batteries ⦿ External antenna jack ⦿ Can be hooked up to attention getting devices ● Strobe lights, pagers, bed shakers, computers, text printers Where Should They Be Kept? ⦿ Near a window in a home or office. ● Receive better reception ⦿ It is a good idea to keep one with sports equipment for emergency alerts. ⦿ Everyone should take one with them while outdoors (boating, camping) or traveling. Getting to Know Your NWR 3 4 1. Programming Buttons 2 2. Select 2 5 3. Menu 1 1 4. Warning Light-Red 6 5. Watch Light- Orange 6. Advisory Light- Yellow 7 7. Weather Radio On/Off Switch 8 8. Volume Up/Down 9 9. Weather/Snooze Button Getting to Know Your NWR: Display Icons 1. Low Battery 3 4 5 Indicator 2 6 1 7 2. Menu Indicator 3. Weather Radio On Indicator 4. Warning Tone Alert 5. Voice Alert 6. Clock Alarm 7. Volume Level Bars 8 8. Alphanumeric Starting Your NWR 1. -

2009 Nationals Notice of Race.Pub

Come fill this river with Mobjackers for the Directions and Accomodations Virginia Governors Cup August 1 and 2 An Invitation to Sail How to get there: then again for the 50th Mobjack Nationals! In the Follow US Route 17 from North or South to the Vil- lage of Gloucester ("Gloucester Courthouse"). Take Business Rt. 17 (Main Street) into the middle of town. 50th Mobjack Turn east on Rt. 3 & 14 at traffic light. Go about 2 National miles, turn right on Rt. 623 (Ware Neck Rd.). Follow WRYC burgee signs to Ware Point Road, look for club Championship entrance on right. For those trailering boats, park in Regatta the large grassy field until ready to launch. The over- head power line is high enough to clear a Mobjack with & Reunion rigged mast. Restrooms with showers are in building on right. The Club House is ahead on right. Accommodations Come home to the Ware River and Mobjack Bay The Comfort Inn on Route 17 just south of Business 17 and .. birthplace of the Mobjack! Celebrate 50 Years! across from the WalMart and Home Depot. Wendy’s is in front of hotel. Three diamond AAA, Platinum Award win- ning hotel. Free continental breakfast, outdoor pool, ADA compliant rooms, and health club privileges. Honeymoon suite with Jacuzzi. All 79 rooms have 25 inch TVs, ironing board, hair dryer, electronic clocks, coffee makers, data phone port and more. (804) 695-1900. North River Inn Bed and Breakfast on 100 waterfront acres at Toddsbury on the North River. Three Historic struc- tures comprise the Inn, Toddsbury Cottage, Toddsbury Guest House and Creek House. -

February 2021 Departmental Reports

COUNTY OF GLOUCESTER CALENDAR OF GOVERNMENTAL MEETINGS MARCH, 2021 Notification of all county public meetings is posted on the main bulletin board at Gloucester County Office Building Two, 6489 Main Street, Gloucester March 1 Board of Supervisors Budget Presentation, 7:00 p.m., (via Electronic Means) March 2 Community Policy Management Team (CPMT), 12:30 p.m., (via Electronic Means) March 2 Board of Supervisors Regular Meeting, 7:00 p.m., (via Electronic Means) March 3 Resource Council Monthly Meeting, 9:30 a.m., (via Electronic Means) March 4 Planning Commission Meeting, 7:00 p.m., (via Electronic Means) March 4 Utilities Advisory Committee, 7:00 p.m., Emergency Operation Center, 7478 Justice Drive, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 9 School Board Regular Meeting, 5:30 p.m., Thomas Calhoun Walker Education Center, 6099 T C Walker Road, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 10 Board of Supervisors Budget Work Session, 7:00 p.m., Page Middle School Auditorium, 5198 T. C. Walker Road, Gloucester, VA 2061 March 10 Wetlands Board / Chesapeake Bay Preservation and Erosion Commission, 7:00 p.m., Colonial Courthouse, 6509 Main Street, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 11 School Board Work Budget Work Session, 5:30 p.m., Thomas Calhoun Walker Education Center, 6099 T C Walker Road, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 16 Board of Supervisors Joint Meeting w/ School Board, 7:00 p.m., Thomas Calhoun Walker Education Center Auditorium, 6680 Short Lane, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 18 Social Services Board Meeting, 7:30 a.m., (via Electronic Means) March 23 Board of Zoning Appeals, 7:00 p.m., (via Electronic Means) March 24 Economic Development Authority, 8:30 a.m., Olivia’s in the Village, 6597 Main Street, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 24 Board of Supervisors Budget Public Hearings, 7:00 p.m., Gloucester High School Auditorium, 6680 Short Lane, Gloucester, VA 23061 March 29 Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee, 7:00 p.m., (Location TBD) *Please note that three or more members of the Board of Supervisors may be in attendance at any of these meetings. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 116, NUMBER 7 (End of Volume) THE BUTTERFLIES OF VIRGINIA (With 31 Plates) BY AUSTIN H. CLARK AND LEILA F. CLARK Smithsonian Institution DEC 89 «f (PUBUCATION 4050) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION DECEMBER 20, 1951 0EC2 01951 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOL. 116, NO. 7, FRONTISPIECE Butterflies of Virginia (From photograph by Frederick M. Bayer. For explanation, see page 195.) SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 116, NUMBER 7 (End of Volume) THE BUTTERFLIES OF VIRGINIA (With 31 Plates) BY AUSTIN H. CLARK AND LEILA F. CLARK Smithsonian Institution z Mi -.££& /ORG (Publication 4050) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION DECEMBER 20, 1951 Zfyt. Borb QBattimovt (preee BALTIMORE, 1ID., D. 6. A. PREFACE Since 1933 we have devoted practically all our leisure time to an intensive study of the butterflies of Virginia. We have regularly spent our annual leave in the State, stopping at various places from which each day we drove out into the surrounding country. In addition to prolonged visits of 2 weeks or more to various towns and cities, we spent many week ends in particularly interesting localities. We have visited all the 100 counties in the State at least twice, most of them many times, and our personal records are from more than 800 locali- ties. We have paid special attention to the Coastal Plain, particularly the great swamps in Nansemond, Norfolk, and Princess Anne Counties, and to the western mountains. Virginia is so large and so diversified that it would have been im- possible for us, without assistance, to have made more than a super- ficial and unsatisfactory study of the local butterflies. -

The Chesapeake, a Boating Guide to Weather

, \. \ I , \ - ,,.-\ ( THE , I CHESAPEAKE: a boating guide to EATHER jon lucy, terry ritter, jerry larue , ...4IL: . .. ·~;t;a· . "'!D'W . .. ".: . .'t.t ii:v;. - . '. :· · . ~)$-:A- .. '··. _ :-~it : .. VIMS SEA GRANT PROGRAM QH 91.15 Virginia Institute of Marine Science .E38 no.25 College of .William and Mary c.l Gloucester Poirit, Virginia THE CHESAPEAKE: a boating guide to WEATHER by Jon Lucy Marine Recreation Specialist Sea Grant Marine Advisory Services Virginia Institute of Marine Science And Instructor, School of Marine Science, College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia Terry Ritter Meteorologist in Charge National Weather Service Norfolk, Virginia Jerry LaRue Meteorologist in Charge National Weather Service Washington, D.C. Educational Series Number 25 First Printing December 1979 Second Printing August 1980 A Cooperative Publication of V IMS Sea Grant Marine Advisory Services and NOAA National Weather Service Acknowledgements For their review and constructive criticism, appreciation is expressed to Messrs. Herbert Groper, Chief, Community Preparedness Staff, Thomas Reppert, Meteorologist, Marine Weather Services Branch and Michael Mogil, Emergency Warning Meteorologist, Public Services Branch, all of NOAA National Weather Service Head quarters, Silver Spring, Maryland; also to Dr. Rollin Atwood, Marine Weather Instructor, U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, Flotilla 33, Kilmarnock, Virginia and Mr. Carl Hobbs, Geological Oceanographer, VIMS. Historical climatological data on Chesa peake Bay was provided by Mr. Richard DeAngelis, Marine Climatological Services Branch, National Oceanographic Data Center, NOAA Environmental Data Service, Washington, D.C. Thanks go to Miss Annette Stubbs of V IMS Report Center for pre paring manuscript drafts and to Mrs. Cheryl Teagle of VIMS Sea Grant Advisory Services for com posing the final text. -

Marine Weather Services Coastal, Offshore and High Seas

A Mariner’s Guide to Marine Weather Services Coastal, Offshore and High Seas U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Weather Service NOAA PA 98054 Introduction Small Craft Forecast winds of 18 to 33 knots. NWS Few people are affected more by weather than the mariner. An Advisory: may also issue Small Craft Advisories for unexpected change in winds, seas, or visibility can reduce the efficiency hazardous sea conditions or lower wind of marine operations and threaten the safety of a vessel and its crew. speeds that may affect small craft The National Weather Service (NWS), a part of the National Oceanic operations. and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), provides marine weather warnings and forecasts to serve all mariners who use the waters for livelihood or recreation. This pamphlet describes marine weather services Gale Warning: Forecast winds of 34 to 47 knots. available from the NWS and other agencies. Storm Warning: Forecast winds of 48 knots or greater. Tropical Storm Forecast winds of 34 to 63 knots Warning: associated with a tropical storm. Warning and Forecast Services Hurricane Forecast winds of 64 knots or higher Warning: associated with a hurricane. The warning and forecast program is the core of the NWS’s responsibility Special Marine Potentially hazardous over-water events to mariners. Warnings and forecasts help the mariner plan and make Warning: of short duration (up to 2 hours). decisions protecting life and property. NWS also provides information through weather statements or outlooks that supplement basic warnings These advisories and warnings are headlined in marine forecasts. and forecasts. -

IN THIS ISSUE Governor Judiciary Regulatory Review and Evaluation Regulations Errata Special Documents General Notices

Issue Date: August 23, 2013 Volume 40 • Issue 17 • Pages 1403—1466 IN THIS ISSUE Governor Judiciary Regulatory Review and Evaluation Regulations Errata Special Documents General Notices Pursuant to State Government Article, §7-206, Annotated Code of Maryland, this issue contains all previously unpublished documents required to be published, and filed on or before August 5, 2013, 5 p.m. Pursuant to State Government Article, §7-206, Annotated Code of Maryland, I hereby certify that this issue contains all documents required to be codified as of August 5, 2013. Brian Morris Acting Administrator, Division of State Documents Office of the Secretary of State Information About the Maryland Register and COMAR MARYLAND REGISTER HOW TO RESEARCH REGULATIONS The Maryland Register is an official State publication published An Administrative History at the end of every COMAR chapter gives every other week throughout the year. A cumulative index is information about past changes to regulations. To determine if there have published quarterly. been any subsequent changes, check the ‘‘Cumulative Table of COMAR The Maryland Register is the temporary supplement to the Code of Regulations Adopted, Amended, or Repealed’’ which is found online at Maryland Regulations. Any change to the text of regulations www.dsd.state.md.us/CumulativeIndex.pdf. This table lists the regulations published in COMAR, whether by adoption, amendment, repeal, or in numerical order, by their COMAR number, followed by the citation to emergency action, must first be published in the Register. the Maryland Register in which the change occurred. The Maryland The following information is also published regularly in the Register serves as a temporary supplement to COMAR, and the two Register: publications must always be used together. -

2000 Data Report Gunpowder River, Patapsco/Back River West Chesapeake Bay and Patuxent River Watersheds

2000 Data Report Gunpowder River, Patapsco/Back River West Chesapeake Bay and Pat uxent River Watersheds Gunpowder River Basin Patapsco /Back River Basin Patuxent River Basin West Chesapeake Bay Basin TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 3 GUNPOWDER RIVER SUB-BASIN ............................................................................. 9 GUNPOWDER RIVER....................................................................................................... 10 LOWER BIG GUNPOWDER FALLS ................................................................................... 16 BIRD RIVER.................................................................................................................... 22 LITTLE GUNPOWDER FALLS ........................................................................................... 28 MIDDLE RIVER – BROWNS............................................................................................. 34 PATAPSCO RIVER SUB-BASIN................................................................................. 41 BACK RIVER .................................................................................................................. 43 BODKIN CREEK .............................................................................................................. 49 JONES FALLS .................................................................................................................. 55 GWYNNS FALLS ............................................................................................................