Chapter 1: Colors First: an Introduction 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study the Status Column Element in the Achaemenid Architecture and Its

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND January 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Study the status column element in the Achaemenid architecture and its effect on India architecture (comparrative research of persepolis columns on pataly putra columns in India) Dr. Amir Akbari* Faculty of History, Bojnourd Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bojnourd, Iran * Corresponding Author Fariba Amini Department of Architecture, Bukan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Bukan, Iran Elham Jafari Department of Architecture, Khoy Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khoy, Iran Abstract In the southern region of Iran and the north of persian Gulf, the state was located in the ancient times was called "pars", since the beginning of the Islamic era its center was shiraz. In this region of Iran a dynasty called Achaemenid came to power and could govern on the very important part of the worlds for years. Achaemenid exploited the skills of artists and craftsman countries under its command. In this sense, in Architecture works and the industry this period is been seen the influence of other nations. Achaemenid kings started to build large and beautiful palaces in the unter of their government and after 25 centuries, the remnants of which still remain firm and after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire by Grecian Alexander in India. The greatest king of India dynasty Muryya, was called Ashoka the grands of Chandra Gupta. The Ashoka palace that id located at the putra pataly around panta town in the state of Bihar in North east India. Is an evidence of the influence of Achaemenid culture in ancient India. The similarity of this city and Ashoka Hall with Apadana Hall in Persepolis in such way that has called it a india persepolis set. -

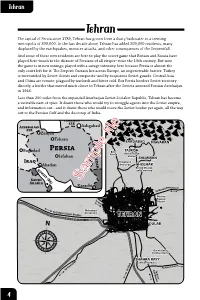

Sample File P’ A Karachi S T Demavend J Oun to M R Doshan Tappan Muscatto Kand Airport

Tehran Tehran Tehran The capital of Persia since 1789, Tehran has grown from a dusty backwater to a teeming metropolis of 800,000. In the last decade alone, Tehran has added 300,000 residents, many displaced by the earthquakes, monster attacks, and other consequences of the Serpentfall. And some of these new residents are here to play the secret game that Britain and Russia have played here–much to the distaste of Persians of all stripes–since the 19th century. But now the game is in new innings; played with a savage intensity here because Persia is almost the only court left for it. The Serpent Curtain lies across Europe, an impenetrable barrier. Turkey is surrounded by Soviet clients and conquests–and by suspicious Soviet guards. Central Asia and China are remote, plagued by warlords and bitter cold. But Persia borders Soviet territory directly, a border that moved much closer to Tehran after the Soviets annexed Persian Azerbaijan in 1946. Less than 200 miles from the expanded Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, Tehran has become Tbilisia veritable nest of spies. It draws those who would try to smuggle agents into the Soviet empire, and information out…and it draws those who would move the Soviet border yet again, all the way out to the PersianBaku Gulf and the doorstep of India.Tashkent T Stalinabad SSR A Ashgabad SSR Zanjan Tehran A S KabulSAADABAD NIAVARAN Damascus Baghdad P Evin TAJRISH Prison Red Air Force Isfahan Station SHEMIRAN I Telephone Jerusalem Abadan Exchange GHOLHAK British Mission and Cemetery R S Sample file P’ A Karachi S t Demavend J oun To M R Doshan Tappan MuscatTo Kand Airport Mehrabad Jiddah To Zanjan (Soviet Border) Aerodrome BombayTEHRAN N O DULAB Gondar A A Aden S Qul’eh Gabri Parthian Ruins SHAHRA RAYY Medieval Ruins To Garm Sar Salt Desert To Hamadan To Qom To Kavir 4 Tehran Tehran THE CHARACTER OF TEHRAN Tehran sits–and increasingly, sprawls–on the southern slopes of the Elburz Mountains, specifically Mount Demavend, an extinct volcano that towers 18,000 feet above sea level. -

Geographic Variation in Mesalina Watsonana (Sauria: Lacertidae) Along a Latitudinal Cline on the Iranian Plateau

SALAMANDRA 49(3) 171–176 30 October 2013 CorrespondenceISSN 0036–3375 Correspondence Geographic variation in Mesalina watsonana (Sauria: Lacertidae) along a latitudinal cline on the Iranian Plateau Seyyed Saeed Hosseinian Yousefkhani 1, Eskandar Rastegar-Pouyani 1, 2 & Nasrullah Rastegar-Pouyani 1 1) Iranian Plateau Herpetology Research Group (IPHRG), Faculty of Science, Razi University, 6714967346 Kermanshah, Iran 2) Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Hakim Sabzevari University, Sabzevar, Iran Corresponding author: Seyyed Saeed Hosseinian Yousefkhani, email: [email protected] Manuscript received: 23 January 2013 Iran is geologically structured by several major mountain We also examined the extent of sexual dimorphism as ranges, plateaus and basins, including the Zagros and El- evident in the 28 metric and meristic characters examined burz Mountains, the Central Plateau, and the Eastern between the 39 adult males (15 Zagros; 10 South; 14 East) Highlands (Berberian & King 1981). Mesalina watson and 21 adult females (Tab. 3) by means of statistical analy- ana (Stoliczka, 1872) is one of the 14 species of the genus sis. The analyses were run using ANOVA and with SPSS Mesalina Gray, 1838 and has a wide distribution range in 16.0 for a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) based Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, NW India and some parts of on the correlation matrix of seven characters to identify Turkmenistan (Anderson 1999, Rastegar-Pouyani et al. groups that were possibly clustered. While 21 of the char- 2007, Khan 2006). It is well known that size and morpho- acter states examined proved to show no significant varia- logical adaptations of a species are closely linked to its habi- tion between the two latitudinal zones, the seven that had tat selection, determine its capability of colonising an area, P-values of < 0.05 (Tab. -

Eclectic Antiquity Catalog

Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes Eclectic Antiquity the Classical Collection of the Snite Museum of Art Compiled and edited by Robin F. Rhodes © University of Notre Dame, 2010. All Rights Reserved ISBN 978-0-9753984-2-5 Table of Contents Introduction..................................................................................................................................... 1 Geometric Horse Figurine ............................................................................................................. 5 Horse Bit with Sphinx Cheek Plates.............................................................................................. 11 Cup-skyphos with Women Harvesting Fruit.................................................................................. 17 Terracotta Lekythos....................................................................................................................... 23 Marble Lekythos Gravemarker Depicting “Leave Taking” ......................................................... 29 South Daunian Funnel Krater....................................................................................................... 35 Female Figurines.......................................................................................................................... 41 Hooded Male Portrait................................................................................................................... 47 Small Female Head...................................................................................................................... -

C01384460 Approved for Release: 2014/02/26

C01384460 Approved for Release: 2014/02/26 APPLIND1X A . ;hose Dil? An Abbreviated History of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Dispute,-'194; -53 In 1372, the then Shah of Persia, rlaser ad-Din, in return for much needed cash, gave to Baron Paul Julius de Reuter. .'a concession to. exploit all his country's minerals (except for gold, silver, and precious stones'), all its forests and uncultivated land, and ail canals and irrigation works, as ;sell as a monopoly to construct railways and tranilways. Although the resulting uproar,-zsrac:.a11~ from neighboring Russiaraused this sweeping concession to be cancelled, de Reuter, who was a German Jew with British citizenship, persisted and by 1889 regained two parts of his original concession--the operation of a bank and the working of Persia's mines. Under the latter grant, de Reuter's men explored-for oil without great success, and the concession expired in 1999, 'the year the Baron died.` Persian oil right Shen passed to a British speculator, William Knox D'Arcy, whose first fortune had been made in Australian gold mines: The purchase price of the concession was about 50,000 pounds, and in 1903 the enterprise began to sell shares in "The First Exploitation Company." Exploratory drilling proceeded, and by 1904, two producing wells were in. a,+A - Shortly thereafter,Ainterest in oil was sharply stimulated by the efforts of Admiral Sir John Fisher, First Lord of the Admiralty, to convert the Royal Navy.from'burning coal to oil.. As a result, the Burmah Oil Company sought to become involved in eersian oil and, joining with D "lrcy and Lord Strathcona, formed the new Concessions Syndicate, L d, which endured un'ti'l 1907 when Burmah Oil bought D'Arcy out for 200„000 pounds cash and 900,000 pounds in shares. -

Anthropoid Coffins ⁄Eran Arie

Canaanites employed at both sites seem to have been inspired 11 lids in the Israel Museum Collection (most originally in the by the cultic activities there. Canaanite tombs of this period Dayan Collection and presumably from Deir el-Balah) have include a large number of Egyptian scarabs bearing images and been published (fig. 20). A coffin in the collection of the Hecht names of gods, but there is no evidence for the actual worship Museum, Haifa, and lids in the Bible Lands Museum, Jerusalem, of these gods by Canaanites, nor is there clear evidence for the all probably originating in Deir el-Balah, are still unpublished. existence in Canaan of temples dedicated to Egyptian gods. In addition, an anthropoid coffin made from chalk was found in Rather, the evidence suggests that, as in the Hyksos Period (but the course of salvage excavations at the site (Tomb 111), the only on an even larger scale), the Canaanites incorporated Egyptian stone anthropoid coffin to have come to light in the country thus prestige symbols into their cultural sphere but did not adopt far. Unfortunately, robbers had already destroyed its lid where Egyptian religious beliefs. the face had been in order to reach the treasures inside (and the coffin itself was robbed at a subsequent date). Finally, in the References: Egyptian fortress excavated at Deir el-Balah, northeast of the Albright 1941; Cornelius 1994; Cornelius 2004; Dothan 1979; Dothan cemetery, twenty additional fragments of coffins were found. 2008; Oren 1973; Tazawa 2009. Tests performed on the coffins from Deir el-Balah revealed that some had been discovered near the kilns in which they had been produced. -

Ancient Babylon: from Gradual Demise to Archaeological Rediscovery

Dr. J. Paul Tanner Daniel: Introduction Archaeol. Rediscovery of Babylon Appendix P Ancient Babylon: From Gradual Demise To Archaeological Rediscovery by Dr. J. Paul Tanner INTRODUCTION: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The Neo-Babylonian Empire was founded under the rule of Nabopolassar (Nabu-apla-usur), who reigned from 626-605 BC . For several hundred years prior to his rule, the Babylonians had been a vassal state under the rule of the Assyrians to the north. In fact Babylon had suffered destruction upon the order of the Assyrian king Sennacherib in 689 BC .1 Following the death of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal in 627 BC , however, the Assyrian Empire rapidly decreased in power until finally in 612 BC the great city of Nineveh was defeated by the combined forces of the Babylonians, Medes and Scythians. A relief from the palace of Ashurbanipal (669-627 BC ) at Kuyunjik (i.e., Nineveh). The king pours a libation over four dead lions before an offering table and incense stand. 1 Klengel-Brandt points out that the earliest mention of the tower (or ziggurat) in a historical inscription comes from the records of Sennacherib, in which he claims to have destroyed Esagila and the temple tower (Eric M. Meyers, ed. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 1997), s.v. "Babylon," by Evelyn Klengel-Brandt, 1:251. Sennacherib's son, Esarhaddon (r. 680-669 BC ), rescinded his father's policy and undertook the rebuilding of Babylon (though retaining the image of Marduk in Assyria that Sennacherib had removed). May 14, 2002 App. -

Decoding Geometry, Proportions and Its Relationship with Aesthetics in Traditional Iranian Architecture

Original Article Decoding geometry, proportions and its relationship with aesthetics in traditional Iranian architecture Shayan Mahmoudi *, Ali Rezvani, Seyed Alireza Hosseini Vahdat Bachelor degree in Architecture, Shahid Beheshti Technical and Vocational Junior College, Karaj Branch, Department of Art and Architecture, Karaj, Iran. Abstract Certain proportions can be observed in creation and design of nature various forms. These proportions are geometrical relationships that are immaterial in origin and follow the spiritual and supernatural principles of their subject sacredness and have symbolic language and spiritual characteristics. Geometry was inseparable from other four Pythagorean sciences in traditional world, including geometric relationships, arithmetic (number), music and astronomy. We always need geometry knowledge in order to construct a building from first steps to final steps. Using proportions is particularly important because of creating visual aesthetic in visual and architectural arts, and almost all artworks are based on some form of proportion. This research tries to decode the work and find the aim and true purpose of its creator in responding the hypothesis that architect knowledge of geometry and his creative use facilitates the conversion of concept into space and form in designing process and minimizes concept erosion of process through studying architecture, geometry and existing proportions. The results obtained from library and field studies by descriptive-analytical method show that different proportions -

Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and the Transformation of Divine Simplicity Andrew Radde-Gallwitz (2009) The Asceticism of Isaac of Nineveh Patrik Hagman (2010) Palladius of Helenopolis The Origenist Advocate Demetrios S. Katos (2011) Origen and Scripture The Contours of the Exegetical Life Peter Martens (2012) Activity and Participation in Late Antique and Early Christian Thought Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2012) Irenaeus of Lyons and the Theology of the Holy Spirit Anthony Briggman (2012) Apophasis and Pseudonymity in Dionysius the Areopagite “No Longer I” Charles M. Stang (2012) Memory in Augustine’s Theological Anthropology Paige E. Hochschild (2012) Orosius and the Rhetoric of History Peter Van Nuffelen (2012) Drama of the Divine Economy Creator and Creation in Early Christian Theology and Piety Paul M. Blowers (2012) Embodiment and Virtue in Gregory of Nyssa Hans Boersma (2013) The Chronicle of Seert Christian Historical Imagination in Late Antique Iraq PHILIP WOOD 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries # Philip Wood 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. -

Redescoperirea Asiriei În Secolul Al Xix-Lea

REDESCOPERIREA ASIRIEI ÎN SECOLUL AL XIX-LEA. SAPATURILE ARHEOLOGICE INTREPRINSE DE VICTOR PLACE LA KHORSABAD REDESCOPERIREA ASIRIEI ÎN SECOLUL AL XIX-LEA. SĂPĂTURILE ARHEOLOGICE INTREPRINSE DE VICTOR PLACE LA KHORSABAD THE REDISCOVERY OF ASSYRIA IN THE 19TH CENTURY. THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS OF VICTOR PLACE AT KHORSABAD Alexandra Mărăşoiu∗ Abstract The purpose of this article is to present the archaeological activity of French diplomat Victor Place. During 1851-1855, when he was consul in Mosul, Victor Place had also an archaeological mission, having been charged by the Academy of Inscriptions and Belles-Lettres in Paris with undertaking excavations at Khorsabad, the site of the ancient city of Durr-Sharukkin, built by Assyrian king Sargon II in the 8th century B.C. Place managed to uncover the palace of Sargon II and collected various Assyrian antiquities which were intended to be exhibited at the Louvre. But unfortunately most of his findings were lost in a shipwreck that took place in April 1855. After his post in Mosul, Victor Place was named consul in Moldova (1855-1863) where he met his wife, Louise Emmeline Ballif, and where he settled after his retirement in 1873. Thanks to his connections with Romania, the National Museum of Romanian History is today owner of an Assyrian cylinder-barrel, with an inscription recounting the reign of Sargon II, that was acquired from a descendant of Victor Place’s. Keywords: archaeology, Victor Place, Khorsabad, Assyrian antiquities, 19th century. Victor Place, care în calitate de consul al Franţei în Moldova între 1855- 1863 a sprijinit crearea Principatelor Unite ale Ţării Româneşti şi Moldovei şi dubla alegere a lui Alexandru Ioan Cuza, a fost nu numai un bun diplomat, ci şi-a câştigat şi un loc de seamă în istoria arheologiei universale, datorită săpăturilor întreprinse la Khorsabad între 1851-1855, în urma cărora a dezvelit ruinele ∗ Documentarist, Secţia Istorie. -

Script Épisode 1

Episode 1 : jane celle qui portait la culotte GENERIQUE DE DEBUT _________________________________________________________ Johanna : Vous voyez l'église de la Dalbade dans le quartier des Carmes à Toulouse ? Eh bien c'est là qu'elle est née. En 1851. "Elle", c'est Jeanne Magre. Une petite fille qui deviendra une grande dame : Jane Dieulafoy. Une des premières femmes françaises à recevoir la Légion d'Honneur, une pionnière de l’archéologie et celle qui a pu être autorisée à porter… - tenez vous bien - un pantalon ! Laissez-moi vous raconter l'histoire de Jane archéologue et romancière, oubliée de la grande Histoire. VIRGULE _________________________________________________________ Lancement : Johanna : Depuis toute petite, Jeanne a toujours aimé les trucs de garçon. Avec son grand frère, elle avait l'habitude de faire des promenades à cheval. Jane : ...des promenades à cheval. Mon papa et ma maman appartiennent à la bourgeoisie toulousaine. Papa fait du commerce, maman ne travaille pas. Moi, ce que j'aime, c'est le dessin et la peinture. Dès l'âge de onze ans, mes parents me placent dans un Institut catholique en banlieue parisienne. J'étudie la littérature, le latin, le grec, mais aussi … les civilisations anciennes. Ça devient une vraie passion. Vous verrez ;-) À 18 ans, je rencontre Marcel Dieulafoy et je tombe amoureuse de lui. Je vous en parle parce que c'est un élément important de mon récit. À cette époque, il travaille au service des édifices municipaux de la ville rose. Un an plus tard, en 1870, on se marie. Mais la même année, la guerre éclate entre la France et la Prusse. -

Marten Stol WOMEN in the ANCIENT NEAR EAST

Marten Stol WOMEN IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Marten Stol Women in the Ancient Near East Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson ISBN 978-1-61451-323-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-1-61451-263-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-1-5015-0021-3 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. Original edition: Vrouwen van Babylon. Prinsessen, priesteressen, prostituees in de bakermat van de cultuur. Uitgeverij Kok, Utrecht (2012). Translated by Helen and Mervyn Richardson © 2016 Walter de Gruyter Inc., Boston/Berlin Cover Image: Marten Stol Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz GmbH & Co. KG, Lemförde Printing and binding: cpi books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Introduction 1 Map 5 1 Her outward appearance 7 1.1 Phases of life 7 1.2 The girl 10 1.3 The virgin 13 1.4 Women’s clothing 17 1.5 Cosmetics and beauty 47 1.6 The language of women 56 1.7 Women’s names 58 2 Marriage 60 2.1 Preparations 62 2.2 Age for marrying 66 2.3 Regulations 67 2.4 The betrothal 72 2.5 The wedding 93 2.6