The Persistence of Casuistry: a Neo-Premodernist Approach to Moral Reasoning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’

Journal of Moral Theology, Vol. 6, Special Issue 2 (2017): 112-137 Seventeenth-Century Casuistry Regarding Persons with Disabilities: Antonino Diana’s Tract ‘On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind’ Julia A. Fleming N 1639, THE FAMOUS THEATINE casuist Antonino Diana published the fifth part of his Resolutiones morales, a volume that included a tract regarding the mute, deaf, and blind.1 Structured I as a series of cases (i.e., questions and answers), its form resembles tracts in Diana’s other volumes concerning members of particular groups, such as vowed religious, slaves, and executors of wills.2 While the arrangement of cases within the tract is not systematic, they tend to fall into two broad categories, the first regarding the status of persons with specified disabilities in the Church and the second in civil society. Diana draws the cases from a wide variety of sources, from Thomas Aquinas and Gratian to later experts in theology, pastoral practice, canon law, and civil law. The tract is thus a reference collection rather than a monograph, although Diana occasionally proposes a new question for his colleagues’ consideration. “On the Mute, Deaf, and Blind” addresses thirty-seven different cases, some focused upon persons with a single disability, and others, on persons with combination of these three disabilities. Specific cases hinge upon further distinctions. Is the individual in question completely or partially blind, totally deaf or hard of hearing, mute or beset with a speech impediment? Was the condition present from birth 1 Antonino Diana, Resolutionum moralium pars quinta (hereafter RM 5) (Lyon, France: Sumpt. -

Averroes's Dialectic of Enlightenment

59 AVERROES'S DIALECTIC OF ENLIGHTENMENT. SOME DIFFICULTIES IN THE CONCEPT OF REASON Hubert Dethier A. The Unity ofthe Intellect This theory of Averroes is to be combated during the Middle ages as one of the greatest heresies (cft. Thomas's De unitate intellectus contra Averroystas); it was active with the revolutionary Baptists and Thomas M"Unzer (as Pinkstergeest "hoch liber alIen Zerstreuungen der Geschlechter und des Glaubens" 64), but also in the "AufkHinmg". It remains unclear on quite a few points 65. As far as the different phases of the epistemological process is concerned, Averroes reputes Avicenna's innovation: the vis estimativa, as being unaristotelian, and returns to the traditional three levels: senses, imagination and cognition. As far as the actual abstraction process is concerned, one can distinguish the following elements with Avicenna. 1. The intelligible fonns (intentiones in the Latin translation) are present in aptitude and in imaginative capacity, that is, in the sensory images which are present there; 2. The fonns are actualised by the working of the Active Intellect (the lowest celestial sphere), that works in analogy to light ; 3. The intelligible fonns-in-act are "received" by the "possible" or the "material intellecf', which thereby changes into intellect-in-act, also called: habitual or acquired intellect: the. perfect form ofwhich - when all scientific knowledge that can be acquired, has been acquired -is called speculative intellect. 4. According to the Aristotelian principle that the epistemological process and knowing itselfcoincide, the state ofintellect-in-act implies - certainly as speculative intellect - the conjunction with the Active Intellect. 64 Cited by Ernst Bloch, Avicenna und die Aristotelische Linke, (1953), in Suhrkamp, Gesamtausgabe, 7, p. -

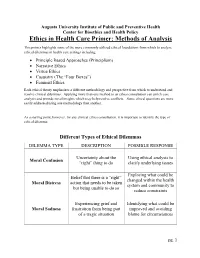

Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis

Augusta University Institute of Public and Preventive Health Center for Bioethics and Health Policy Ethics in Health Care Primer: Methods of Analysis This primer highlights some of the more commonly utilized ethical foundations from which to analyze ethical dilemmas in health care settings including: • Principle Based Approaches (Principlism) • Narrative Ethics • Virtue Ethics • Casuistry (The “Four Boxes”) • Feminist Ethics Each ethical theory emphasizes a different methodology and perspective from which to understand and resolve clinical dilemmas. Applying more than one method to an ethics consultation can enrich case analysis and provide novel insights which may help resolve conflicts. Some ethical questions are more easily addressed using one methodology than another. As a starting point, however, for any clinical ethics consultation, it is important to identify the type of ethical dilemma: Different Types of Ethical Dilemmas DILEMMA TYPE DESCRIPTION POSSIBLE RESPONSE Uncertainty about the Using ethical analysis to Moral Confusion “right” thing to do clarify underlying issues Exploring what could be Belief that there is a “right” changed within the health Moral Distress action that needs to be taken system and community to but being unable to do so reduce constraints Experiencing grief and Identifying what could be Moral Sadness frustration from being part improved and avoiding of a tragic situation blame for circumstances pg. 1 Principlism Principlism refers to a method of analysis utilizing widely accepted norms of moral agency (the ability of an individual to make judgments of right and wrong) to identify ethical concerns and determine acceptable resolutions for clinical dilemmas. In the context of bioethics, principlism describes a method of ethical analysis proposed by Beauchamp and Childress, who believe that there are four principles central in the ethical practice of health care1: 1. -

The Toulmin Model Meets Critical Rhetoric

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor OSSA Conference Archive OSSA 6 Jun 1st, 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Induction and Invention: The Toulmin Model Meets Critical Rhetoric Satoru Aonuma Kanda University of International Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive Part of the Philosophy Commons Aonuma, Satoru, "Induction and Invention: The Toulmin Model Meets Critical Rhetoric" (2005). OSSA Conference Archive. 2. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/ossaarchive/OSSA6/papers/2 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Conference Proceedings at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in OSSA Conference Archive by an authorized conference organizer of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Induction and Invention: The Toulmin Model Meets Critical Rhetoric SATORU AONUMA Department of International Communication Kanda University of International Studies 1-4-1 Wakaba, Mihama Chiba 261-0014 JAPAN [email protected] ABSTRACT: The aim of this paper is to (re)articulate the relationship between "critical rhetoric" and Stephen Toulmin's conception of practical reasoning. Among students of rhetoric, particularly those who work in communication departments in (US) American universities, the project of reason, once cherished as central to the 20th century Renaissance of argument, seems to have become outdated and irrelevant. With the recent “critical turn,” reason was especially given a bad name in the field of rhetoric. Some rhetoricians have even joined reason’s Other, dissociating themselves from the project of reason as much as possible. The paper contends that the difference between critical reasoners and rhetoricians is not so substantial as it may look. -

Reconceiving Curriculum: an Historical Approach Stephen Shepard Triche Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Reconceiving curriculum: an historical approach Stephen Shepard Triche Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Triche, Stephen Shepard, "Reconceiving curriculum: an historical approach" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 495. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/495 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. RECONCEIVING CURRICULUM: AN HISTORICAL APPROACH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In The Department of Curriculum and Instruction by Stephen S. Triche B.A., Louisiana State University, 1979 M.A.. Louisiana State University, 1991 August 2002 To my family for their love and support over the years as I pursue this dream and to the memory of my father. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The process of researching and writing this dissertation has brought many teachers into my life—those special people who have given me their time and unique talents. First, and foremost, I wish to thank Dr. William Doll for his unwavering confidence and determination to bring out the best that I could give. Without his wisdom and support this project could not have been accomplished. -

Philosophy and the Art of Living Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel

Philosophy and the Art of Living Osher Life-Long Learning Institute (UC Irvine) 2010 The Masters of Reason and the Masters of Suspicion: Aristotle, Spinoza, Hegel Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Sartre When: Mondays for six weeks: November 1 ,8, 15, 22, 29, and Dec. 6. Where: Woodbridge Center, 4628 Barranca Pkwy. Irvine CA 92604 NOTES AND QUOTES: Aristotle: 384 BCE- 322 BCE (62 years): Reference: http://www.jcu.edu/philosophy/gensler/ms/arist-00.htm Theoretical Reason contemplates the nature of Reality. Practical Reason arranges the best means to accomplish one's ends in life, of which the final end is happiness. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-ethics/#IntVir Aristotle distinguishes two kinds of virtue (1103a1-10): those that pertain to the part of the soul that engages in reasoning (virtues of mind or intellect), and those that pertain to the part of the soul that cannot itself reason but is nonetheless capable of following reason (ethical virtues, virtues of character). Intellectual virtues are in turn divided into two sorts: those that pertain to theoretical reasoning, and those that pertain to practical thinking 1139a3-8). He organizes his material by first studying ethical virtue in general, then moving to a discussion of particular ethical virtues (temperance, courage, and so on), and finally completing his survey by considering the intellectual virtues (practical wisdom, theoretical wisdom, etc.). Life : Aristotle was born in northern Greece in 384 B.C. He was raised by a guardian after the death of his father, Nicomachus, who had been court physician to the king of Macedonia. Aristotle entered Plato's Academy at age 17. -

Contributing to a Better Understanding of the Contemporary Debate

ABCD springer.com Contributing to a better understanding of the contemporary debate A Treatise of Legal Philosophy and General Jurisprudence S 6–8 VOLUME Editor-in-Chief: Enrico Pattaro, CIRSFID and Law Faculty, University of Bologna, Italy Now Available! The fi rst ever multivolume treatment of the issues in legal philosophy and general jurisprudence, from both a theoretical and a historical perspective. A classical reference work that would be of great interest to legal and practical philosophers, as well as jurists and Philosophy of Law-scholar at all levels The entire work is divided into three parts: The Theoretical part (published in 2005) consists of 5 volumes and covers the main topics of contemporary debate. The Historical part consists of 6 volumes and is scheduled to be published during 2006 (volumes 6-8) and 2007 (volumes 9-11) and volume 12 (index). The historical volumes account for the development of legal thought from ancient Greek times through the twentieth century. Vol. 6: A History of the Philosophy of Law from the Ancient Greeks to the Scholastics – 3 Fred D. Miller Jr. E VOLUM Vol. 7: The Jurists’ Philosophy of Law from Rome to the Seventeenth Century – SET Andrea Padovani & Peter Stein Vol. 8: A History of the Philosophy of Law from the Seventeenth Century to 1900 in the Common-Law Tradition – Diethelm Klippel 2006, 1.090 p. (3 volume set), Harcover ISBN 1-4020-4950-1 € 399,00 | £307.00 | $535.00 Easy Ways to Order for the Americas Write: Springer Order Department, PO Box 2485, Secaucus, NJ 07096-2485, USA Call: (toll free) 1-800-SPRINGER Fax: +1(201)348-4505 Email: [email protected] or for outside the Americas Write: Springer Distribution Center GmbH, Haberstrasse 7, 69126 Heidelberg, Germany Call: +49 (0) 6221-345-4301 Fax : +49 (0) 6221-345-4229 Email: [email protected] Prices are subject to change without notice. -

Contradiction and Aporia in Early Greek Philosophy John Palmer

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-11015-1 — The Aporetic Tradition in Ancient Philosophy Edited by George Karamanolis , Vasilis Politis Excerpt More Information chapter 1 Contradiction and Aporia in Early Greek Philosophy John Palmer An aporia is, essentially, a point of impasse where there is puzzlement or perplexity about how to proceed. Aporetic reasoning is reasoning that leads to this sort of impasse, and an aporia-based method would be one that centrally employs such reasoning. One might describe aporia, more basically, as a point where one does not know how to respond to what is said. In the Platonic dialogues dubbed ‘aporetic’, for instance, Socrates brings his interlocutors to the point where they no longer know what to say. Now, it should be obvious that there was a good deal of aporetic reasoning prior to Socrates. It should also be obvious that the form of such reasoning is immaterial so long as it leads to aporia. In particular, the reasoning that leads to an aporia need not take the form of a dilemma. Instances of reasoning generating genuine dilemmas – with two equally unpalatable alternatives presented as exhausting the possibilities – are actually rather rare in early Greek philosophy. Moreover, there need not in fact be any reasoning or argumentation as such to lead an auditor to a point where it is unclear how to proceed or what to say. Logical paradoxes such as Eubulides’ liar do not rely on argumentation at all but on the exploitation of certain logical problems to generate an aporia. All that is required in this instance is the simple question: ‘Is what a man says true or false when he says he is lying?’ It is hard to know how to answer this question because any simple response snares one in contradiction. -

Early Medieval G

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Religious Studies Faculty Publications Religious Studies 2001 History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval G. Scott aD vis University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/religiousstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Ethics in Religion Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Davis, G. Scott. "History of Western Ethics: Early Medieval." In Encyclopedia of Ethics, edited by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker, 709-15. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge, 2001. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval Copyright 2001 from Encyclopedia of Ethics by Lawrence Becker and Charlotte Becker. Reproduced by permission of Taylor and Francis, LLC, a division of Informa plc. history of Western ethics: 5. Early Medieval ''Medieval" and its cognates arose as terms of op probrium, used by the Italian humanists to charac terize more a style than an age. Hence it is difficult at best to distinguish late antiquity from the early middle ages. It is equally difficult to determine the proper scope of "ethics," the philosophical schools of late antiquity having become purveyors of ways of life in the broadest sense, not clearly to be distin guished from the more intellectually oriented ver sions of their religious rivals. This article will begin with the emergence of philosophically informed re flection on the nature of life, its ends, and respon sibilities in the writings of the Latin Fathers and close with the twelfth century, prior to the systematic reintroduction and study of the Aristotelian corpus. -

NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, and the FUNCTION of CONSCIENCE in THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan –

Diametros 47 (2016): 1–18 doi: 10.13153/diam.47.2016.865 NARRATIVE, CASUISTRY, AND THE FUNCTION OF CONSCIENCE IN THOMAS AQUINAS – Stephen Chanderbhan – Abstract. Both the function of one’s conscience, as Thomas Aquinas understands it, and the work of casuistry in general involve deliberating about which universal moral principles are applicable in particular cases. Thus, understanding how conscience can function better also indicates how casuistry might be done better – both on Thomistic terms, at least. I claim that, given Aquinas’ de- scriptions of certain parts of prudence (synesis and gnome) and the role of moral virtue in practical knowledge, understanding particular cases more as narratives, or parts of narratives, likely will result, all else being equal, in more accurate moral judgments of particular cases. This is especially important in two kinds of cases: first, cases in which Aquinas recognizes universal moral principles do not specify the means by which they are to be followed; second, cases in which the type-identity of an action – and thus the norms applicable to it – can be mistaken Keywords: Thomas Aquinas, conscience, narrative, casuistry, prudence, virtue, moral judgment, moral development, moral knowledge. Introduction ‘Casuistry’ has a bad reputation in some circles. It tends to be associated wi- th formalized, but too legalistic, approaches to determining and enumerating mo- ral faults. In a more generic sense, though, casuistry just refers to deliberating about and discerning what universal moral principles apply in particular cases, based on relevant details of the case at issue. As Thomas Aquinas understands things, casuistry parallels the ordinary, everyday function of one’s conscience, which specifically regards particular cases in which one deliberates about one’s own morally relevant actions.1 Given this, we might be able to gain insight to how formalized casuistry can be done well by drawing an analogy from what it takes for conscience to function well. -

The Status in 1980 of the Toulmin Model of Argument in the Area of Speech Communication

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1980 The status in 1980 of the Toulmin model of argument in the area of speech communication Jeffrey Robert Sweeney Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Speech and Hearing Science Commons, and the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sweeney, Jeffrey Robert, "The status in 1980 of the Toulmin model of argument in the area of speech communication" (1980). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3164. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.3155 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Jeffrey Robert Sweeney for the Master of Science in Speech Communication presented November 17, 1980. Title: The Status in 1980 of the Toulmin Model of Argument in the Area of Speech Communication. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COM1'1ITTEE: Francis P. Gibson, Chairman Rupert ~- ~ucnanan In 1958 Stephen E. Toulmin wrote of inadequacies of formal logic and proposed a new field-dependent approach to the analysis of arguments. Despite a generally negative response to his proposal from formal logicians, Toulmin's model for the laying out of arguments for analysis was 2 subsequently appropriated by several speech communication textbook writers. In some textbooks, the Toulmin model has become successor to the syllogism as the paradigm of logi cal argument. -

Nietzsche's Platonism

CHAPTER 1 NIETZSCHE’S PLATONISM TWO PROPER NAMES. Even if modified in form and thus conjoined. As such they broach an interval. The various senses of this legacy, of Nietzsche’s Platonism, are figured on this interval. The interval is gigantic, this interval between Plato and Nietzsche, this course running from Plato to Nietzsche and back again. It spans an era in which a battle of giants is waged, ever again repeating along the historical axis the scene already staged in Plato’s Sophist (246a–c). It is a battle in which being is at stake, in which all are exposed to not being, as to death: it is a gigantomac√a p'r¥ t›V o¶s√aV. As the Eleatic Stranger stages it, the battle is between those who drag every- thing uranic and invisible down to earth, who thus define being as body, and those others who defend themselves from an invisible po- sition way up high, who declare that being consists of some kind of intelligibles (nohtº) and who smash up the bodies of the others into little bits in their l¬goi, philosophizing, as it were, with the hammer of l¬goV. Along the historical axis, in the gigantic interval from Plato to Nietzsche, the contenders are similarly positioned for the ever re- newed battle. They, too, take their stance on one side or the other of the interval—again, a gigantic interval—separating the intelligible from the visible or sensible, t¿ noht¬n from t¿ aÎsqht¬n. Those who station themselves way up high are hardly visible from below as they wield their l¬goi and shield themselves by translating their very position into words: m'tΩ tΩ fusikº.