Too Late to Be a Viking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ouch Podcast

Ouch Talk Show 21 December 2016 bbc.co.uk/ouch Presented by Damon Rose, Beth Rose and Emma Tracey Punk Therapy EMMA Before we get into this week’s episode of Inside Ouch I just want to tell you about an event Ouch will be holding in early 2017. It’s a live storytelling night and the theme is love and relationships. So, if you have a suitable story that you fancy telling in front of a live audience email it to [email protected]. Maybe you’re blind and your partner snogged someone right in front of you at a party. Or maybe your differences make intimacy a little tricky. All we ask is that you are disabled, that the story is true and that it’s about disability in some way. Bookmark bbc.co.uk/ouch/disability for further details. Now, let’s get back into this week’s episode of Inside Ouch. [Music playing – Christmas as a Punk] What do you when you’ve turned 18 or finished formal education if you’ve got learning disabilities? Electric Umbrella sought a solution and wound up with an amazing Christmas single, and they’re here on a quest to make Christmas As A Punk number one. This is Inside Ouch; I’m Emma Tracey in Edinburgh. In London we have Damon Rose. DAMON Hello. EMMA We have Beth Rose. BETH Hi there. EMMA And we have three members of Electric Umbrella. Hello. BAND Hello! EMMA Awesome. So, we’ve got Tom Billington. TOM Hello. EMMA Used to be in Mohair touring with Razorlight and the The Killers. -

Record-Business-1982

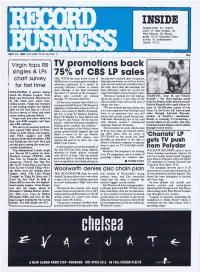

INSIDE Singles chart, 6-7; Album chart, 17; New Singles, 18; New Albums, 19; Airplay guide, 15-15; Quarterly Chart survey, 12; Independent Labels, 12/13. April 12, 1982VOLUME FIVE Number 3 65p Virgin tops RBTV promotions back singles & LPs 75% of CBS LP sales chart survey CBS, WITH the most active roster ofthe industry's national chart was gained, MOR artists, is increasingly resorting toalthough promotion on such an intense television promotion asa means ofscale was not underway anywhere else at for first time securing sufficient volume to ensurethe time. Since then the campaign has chart placings. It has been estimatedbeen efficiently rolled out to give the FOLLOWING A quarter during that about 75 percent of the company'ssinger her highest chart placing to date. which the Human League, Toni albumsalescurrentlyarecoming Television backing for the IglesiasTIGHTFIT, keepfitand Felicity Basil and Orchestral Manoeuvres through TV -boosted repertoire. album has given it a new lease of lifeKendall - the chart -topping group In The Dark were major best- after an earlier chart entry at the time offrom the Zomba stable present actress selling artists, Virgin has emerged Of the seven releases with which it is scoring in the RB Top 60, CBS has givenrelease last year. Felicity Kendall with a gold album for as the leading singles and albums "We are certainly getting volume, butsales of 200,000 -plus copies of her label for the first time in a Record significant smallscreen support to five of them, Love Songs by Barbra Streisand,it is a very expensive way of doing it andShape Up And Dance LP, sold on mail Business survey of chart and sales there is no guarantee that you willorderthroughLifestyleRecords, action during January -March. -

Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate If Seminar And/Or Writing II Course

MUSIC HISTORY 13 PAGE 1 of 14 MUSIC HISTORY 13 General Education Course Information Sheet Please submit this sheet for each proposed course Department & Course Number Music History 13 Course Title Punk: Music, History, Sub/Culture Indicate if Seminar and/or Writing II course 1 Check the recommended GE foundation area(s) and subgroups(s) for this course Foundations of the Arts and Humanities • Literary and Cultural Analysis • Philosophic and Linguistic Analysis • Visual and Performance Arts Analysis and Practice x Foundations of Society and Culture • Historical Analysis • Social Analysis x Foundations of Scientific Inquiry • Physical Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) • Life Science With Laboratory or Demonstration Component must be 5 units (or more) 2. Briefly describe the rationale for assignment to foundation area(s) and subgroup(s) chosen. This course falls into social analysis and visual and performance arts analysis and practice because it shows how punk, as a subculture, has influenced alternative economic practices, led to political mobilization, and challenged social norms. This course situates the activity of listening to punk music in its broader cultural ideologies, such as the DIY (do-it-yourself) ideal, which includes nontraditional musical pedagogy and composition, cooperatively owned performance venues, and underground distribution and circulation practices. Students learn to analyze punk subculture as an alternative social formation and how punk productions confront and are times co-opted by capitalistic logic and normative economic, political and social arrangements. 3. "List faculty member(s) who will serve as instructor (give academic rank): Jessica Schwartz, Assistant Professor Do you intend to use graduate student instructors (TAs) in this course? Yes x No If yes, please indicate the number of TAs 2 4. -

AN ANALYSIS of the MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS of NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 a THESIS S

AN ANALYSIS OF THE MUSICAL INTERPRETATIONS OF NINA SIMONE by JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH B.M., Kansas State University, 2008 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Dale Ganz Copyright JESSIE L. FREYERMUTH 2010 Abstract Nina Simone was a prominent jazz musician of the late 1950s and 60s. Beyond her fame as a jazz musician, Nina Simone reached even greater status as a civil rights activist. Her music spoke to the hearts of hundreds of thousands in the black community who were struggling to rise above their status as a second-class citizen. Simone’s powerful anthems were a reminder that change was going to come. Nina Simone’s musical interpretation and approach was very unique because of her background as a classical pianist. Nina’s untrained vocal chops were a perfect blend of rough growl and smooth straight-tone, which provided an unquestionable feeling of heartache to the songs in her repertoire. Simone also had a knack for word painting, and the emotional climax in her songs is absolutely stunning. Nina Simone did not have a typical jazz style. Critics often described her as a “jazz-and-something-else-singer.” She moved effortlessly through genres, including gospel, blues, jazz, folk, classical, and even European classical. Probably her biggest mark, however, was on the genre of protest songs. Simone was one of the most outspoken and influential musicians throughout the civil rights movement. Her music spoke to the hundreds of thousands of African American men and women fighting for their rights during the 1960s. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Put on Your Boots and Harrington!': the Ordinariness of 1970S UK Punk

Citation for the published version: Weiner, N 2018, '‘Put on your boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress' Punk & Post-Punk, vol 7, no. 2, pp. 181-202. DOI: 10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 Document Version: Accepted Version Link to the final published version available at the publisher: https://doi.org/10.1386/punk.7.2.181_1 ©Intellect 2018. All rights reserved. General rights Copyright© and Moral Rights for the publications made accessible on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Please check the manuscript for details of any other licences that may have been applied and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http://uhra.herts.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or private study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, any such items will be temporarily removed from the repository pending investigation. Enquiries Please contact University of Hertfordshire Research & Scholarly Communications for any enquiries at [email protected] 1 ‘Put on Your Boots and Harrington!’: The ordinariness of 1970s UK punk dress Nathaniel Weiner, University of the Arts London Abstract In 2013, the Metropolitan Museum hosted an exhibition of punk-inspired fashion entitled Punk: Chaos to Couture. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

The Time the Children Didn't Go to School

THE TIME THE CHILDREN DIDN’T GO TO SCHOOL ANNABELLE HAYES FOREWORD ......................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................. 4 APRIL 2020 ............................................................ 5 MAY, 2020 ............................................................ 33 JUNE, 2020 .......................................................... 63 JULY, 2020 ......................................................... 102 AUGUST, 2020 .................................................... 110 SEPTEMBER, 2020 ............................................ 114 OCTOBER, 2020 ............................................... 129 NOVEMBER, 2020 ........................................... 152 DECEMBER, 2020 ............................................ 166 JANUARY, 2021 ................................................. 176 FEBRUARY, 2021 .............................................. 202 MARCH, 2021 .................................................... 223 AFTERWORD ................................................... 230 2 FOREWORD In March 2020, schools, nurseries and colleges in the United Kingdom were shut down in response to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. By 20 March, all schools in the UK had closed to all children except those of key workers and children considered vulnerable. After a month of numbness at having all the children home, I started these diaries to document the unprecedented time when the children didn’t go to school. When the world stopped, the children didn’t – this records their -

Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain

‘Better Decide Which Side You’re On’: Authenticity, Politics and Post-Punk in Thatcherite Britain Doctor of Philosophy (Music) 2014 Joseph O’Connell Joseph O’Connell Acknowledgements Acknowledgements I could not have completed this work without the support and encouragement of my supervisor: Dr Sarah Hill. Alongside your valuable insights and academic expertise, you were also supportive and understanding of a range of personal milestones which took place during the project. I would also like to extend my thanks to other members of the School of Music faculty who offered valuable insight during my research: Dr Kenneth Gloag; Dr Amanda Villepastour; and Prof. David Wyn Jones. My completion of this project would have been impossible without the support of my parents: Denise Arkell and John O’Connell. Without your understanding and backing it would have taken another five years to finish (and nobody wanted that). I would also like to thank my daughter Cecilia for her input during the final twelve months of the project. I look forward to making up for the periods of time we were apart while you allowed me to complete this work. Finally, I would like to thank my wife: Anne-Marie. You were with me every step of the way and remained understanding, supportive and caring throughout. We have been through a lot together during the time it took to complete this thesis, and I am looking forward to many years of looking back and laughing about it all. i Joseph O’Connell Contents Table of Contents Introduction 4 I. Theorizing Politics and Popular Music 1. -

Tim's My Secret Playlist For

My Secret Playlist Artist / band name: Screamfeeder (Tim Steward) Name of track/artist and short write-up on why you like it so much (30-80 words each track): 1. Vitreous Humour / Why Are You So Mean To Me? Later covered by Nada Surf, the original of this 90s indie rock noise-up is by far the superior version. Bottom heavy guitars, squawky vocals, and tempos going up and down like a yoyo; it totally distills the essence of 90s punk rock into 3 minutes and 41 seconds. It makes me wanna get drunk and jump up and down. I shouldn’t drive whilst listening to this song. 2. Thin Lizzy / Running back The secret pop hit hidden on the band’s late 70s opus Jailbreak. This song cannot be played once, it must be on repeat for at least a few hours. Phil’s vocals are gorgeous, and touching, and sweet. The last verse is all nah nah nah nah nah’s and by then no more words are needed, pure gold. 3. The Foo Fighters / Everlong How can a band featuring the ex Nirvana drummer and with half a dozen or so albums out only have one good song? Beats me, but this is a total corker. 4. The Hold Steady / Sweet Payne Everyone knows I think THS fuckin rule, so it’s no surprise they are listed here. This is the second last song on their debut “Almost killed me” what a classic. It sounds so effortless, like they dashed it off after the session was over. -

What Libraries Can Do Michael Sullivan Connecting Boys with Books

Connecting Boys with Books What Libraries Can Do Michael Sullivan Connecting Boys with Books What Libraries Can Do Michael Sullivan American Library Association Chicago 2003 While extensive effort has gone into ensuring the reliability of information appearing in this book, the publisher makes no warranty, express or implied, on the accuracy or relia- bility of the information, and does not assume and hereby disclaims any liability to any person for any loss or damage caused by errors or omissions in this publication. Composition and design by ALA Editions in Aperto and Berkeley using QuarkXPress 5.0 for the PC Printed on 50-pound white offset, a pH-neutral stock, and bound in 10-point coated cover stock by Victor Graphics The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992. ϱ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sullivan, Michael, 1967 Aug. 30- Connecting boys with books : what libraries can do / by Michael Sullivan. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8389-0849-7 (alk. paper) 1. Children’s libraries––Activity programs. 2. Young adults’ libraries––Activity programs. 3. Boys––Books and reading. 4. Reading promotion. 5. Reading––Sex differences. I. Title. Z718.1.S85 2003 028.5Ј5––dc21 2003006962 Copyright © 2003 by the American Library Association. All rights reserved except those which may be granted by Sections 107 and 108 of the Copyright Revision Act of 1976.