The Enchantment of the Common: Ivan Illich's Philosophical Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feminist Philosophy

The Blackwell Guide to Feminist Philosophy Edited by Linda Martín Alcoff and Eva Feder Kittay The Blackwell Guide to Feminist Philosophy Blackwell Philosophy Guides Series Editor: Steven M. Cahn, City University of New York Graduate School Written by an international assembly of distinguished philosophers, the Blackwell Philosophy Guides create a groundbreaking student resource – a complete critical survey of the central themes and issues of philosophy today. Focusing and advancing key arguments throughout, each essay incorporates essential background material serving to clarify the history and logic of the relevant topic. Accordingly, these volumes will be a valuable resource for a broad range of students and readers, including professional philosophers. 1 The Blackwell Guide to EPISTEMOLOGY edited by John Greco and Ernest Sosa 2 The Blackwell Guide to ETHICAL THEORY edited by Hugh LaFollette 3 The Blackwell Guide to the MODERN PHILOSOPHERS edited by Steven M. Emmanuel 4 The Blackwell Guide to PHILOSOPHICAL LOGIC edited by Lou Goble 5 The Blackwell Guide to SOCIAL AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY edited by Robert L. Simon 6 The Blackwell Guide to BUSINESS ETHICS edited by Norman E. Bowie 7 The Blackwell Guide to the PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE edited by Peter Machamer and Michael Silberstein 8 The Blackwell Guide to METAPHYSICS edited by Richard M. Gale 9 The Blackwell Guide to the PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION edited by Nigel Blake, Paul Smeyers, Richard Smith, and Paul Standish 10 The Blackwell Guide to PHILOSOPHY OF MIND edited by Stephen P. Stich and Ted A. Warfi eld 11 The Blackwell Guide to the PHILOSOPHY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES edited by Stephen P. -

The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler

Chapter 3 The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler Peter J. Colosi In a way, his [Pope John Paul II’s] undisputed contribution to Christian thought can be understood as a profound meditation on the person. He enriched and expanded the concept in his encyclicals and other writings. These texts represent a patrimony to be received, collected and assimilated with care.1 - Pope Benedict XVI INTRODUCTION Throughout the writings of Karol Wojtyła, both before and after he became Pope John Paul II, one finds expressions of gratitude and indebtedness to the philosopher Max Scheler. It is also well known that in his Habilitationsschrift,2 Wojtyła concluded that Max Scheler’s ethical system cannot cohere with Christian ethics. This state of affairs gives rise to the question: which of the ideas of Scheler did Wojtyła embrace and which did he reject? And also, what was Wojtyła’s overall attitude towards and assessment of Scheler? A look through all the works of Wojtyła reveals numerous expressions of gratitude to Scheler for philosophical insights which Wojtyła embraced and built upon, among them this explanation of his sources for The Acting Person, Granted the author’s acquaintance with traditional Aristotelian thought, it is however the work of Max Scheler that has been a major influence upon his reflection. In my overall conception of the person envisaged through the mechanisms of his operative systems and their variations, as presented here, may indeed be seen the Schelerian foundation studied in my previous work.3 I have listed many further examples in the appendix to this paper. -

PHIL 101.Pdf

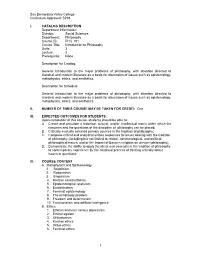

San Bernardino Valley College Curriculum Approved: SP01 I. CATALOG DESCRIPTION Department Information: Division: Social Sciences Department: Philosophy Course ID: PHIL 101 Course Title: Introduction to Philosophy Units: 3 Lecture: 3 Prerequisite: None Description for Catalog: General introduction to the major problems of philosophy, with attention directed to classical and modern literature as a basis for discussion of issues such as epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. Description for Schedule: General introduction to the major problems of philosophy, with attention directed to classical and modern literature as a basis for discussion of issues such as epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. II. NUMBER OF TIMES COURSE MAY BE TAKEN FOR CREDIT: One III. EXPECTED OUTCOMES FOR STUDENTS: Upon completion of this course, students should be able to: A. Create and articulate a historical, cultural, and/or intellectual matrix within which the concerns and the questions of the discipline of philosophy can be placed; B. Critically evaluate selected primary sources in the tradition of philosophy; C. Compose critical and analytical written responses to issues dealing with the tradition of philosophy (including but not limited to ethical, epistemological, and political philosophical issues, and/or the impact of Eastern religions on western philosophy); D. Demonstrate the ability to apply the ideas and concepts in the tradition of philosophy to contemporary experience by the continual process of thinking critically about issues or questions IV. COURSE CONTENT A. Metaphysics and Epistemology 1. Skepticism 2. Rationalism 3. Empiricism 4. Kantian constructivism 5. Epistemological relativism 6. Existentialism 7. Feminist epistemology 8. The mind-body problem 9. Freedom and determinism 10. -

The Sceptics: the Arguments of the Philosophers

THE SCEPTICS The Arguments of the Philosophers EDITOR: TED HONDERICH The purpose of this series is to provide a contemporary assessment and history of the entire course of philosophical thought. Each book constitutes a detailed, critical introduction to the work of a philosopher of major influence and significance. Plato J.C.B.Gosling Augustine Christopher Kirwan The Presocratic Philosophers Jonathan Barnes Plotinus Lloyd P.Gerson The Sceptics R.J.Hankinson Socrates Gerasimos Xenophon Santas Berkeley George Pitcher Descartes Margaret Dauler Wilson Hobbes Tom Sorell Locke Michael Ayers Spinoza R.J.Delahunty Bentham Ross Harrison Hume Barry Stroud Butler Terence Penelhum John Stuart Mill John Skorupski Thomas Reid Keith Lehrer Kant Ralph C.S.Walker Hegel M.J.Inwood Schopenhauer D.W.Hamlyn Kierkegaard Alastair Hannay Nietzsche Richard Schacht Karl Marx Allen W.Wood Gottlob Frege Hans D.Sluga Meinong Reinhardt Grossmann Husserl David Bell G.E.Moore Thomas Baldwin Wittgenstein Robert J.Fogelin Russell Mark Sainsbury William James Graham Bird Peirce Christopher Hookway Santayana Timothy L.S.Sprigge Dewey J.E.Tiles Bergson A.R.Lacey J.L.Austin G.J.Warnock Karl Popper Anthony O’Hear Ayer John Foster Sartre Peter Caws THE SCEPTICS The Arguments of the Philosophers R.J.Hankinson London and New York For Myles Burnyeat First published 1995 by Routledge First published in paperback 1998 Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1995 R.J.Hankinson All rights reserved. -

An Outline of Philosophy Free

FREE AN OUTLINE OF PHILOSOPHY PDF Bertrand Russell | 352 pages | 06 Apr 2009 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415473453 | English | London, United Kingdom Outline of philosophy - Wikipedia For younger readers and those with short attention spanshere is my own abbreviated and An Outline of Philosophy history of Western Philosophy, all on one long page. The explanations are necessarily simplistic and lacking in detail, though, and the links should be followed for more information. Thales of Miletus is usually considered the first proper philosopher, although he An Outline of Philosophy just as concerned with natural philosophy what we now call science as with philosophy as we know it. Thales and most of the other Pre-Socratic philosophers i. They were Materialists they believed that all things are composed of material and nothing else and were mainly concerned with trying to establish the single underlying substance the world is made up of a kind of Monismwithout resorting to supernatural or mythological explanations. For instance, Thales thought the whole universe was composed of different forms of water ; Anaximenes concluded it was made of air ; Heraclitus thought it was fire ; and Anaximander some unexplainable substance usually translated as " the infinite " or " the boundless ". Another issue the Pre- Socratics wrestled with was the so-called problem of changehow things appear to change from one form to another. At the extremes, Heraclitus believed in an on-going process of perpetual changea constant interplay of opposites ; Parmenideson the An Outline of Philosophy hand, using a complicated deductive argument, denied that there was any such thing as change at all, and argued that everything that exists is permanentindestructible and unchanging. -

THOUGHT EXPERIMENTS Thispage Intentionally !Efi Blank THOUGHT EXPERIMENTS

ROY A. SORENSEN THOUGHT EXPERIMENTS Thispage intentionally !efi blank THOUGHT EXPERIMENTS ROY A. SORENSEN OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS New York Oxford Oxford University Press Oxford New York Athens Auckland Bangkok Bogota Buenos Aires Calcutta Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Florence Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi Paris Săo Paulo Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto Warsaw and associated companies in Berlin lbadan Copyright © 1992 by Roy A. Sorensen First published in 1992 by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Av enue, New York, New York 10016 First Issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 1998 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press, !ne. AU rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sorensen, Roy A. Thought expriments Roy A. Sorensen p. cm. Includes bibliographica1 references and index. ISBN 0-19-507422-X ISBN 0-19-512913-X (pbk.) 1 Thought and thinking. 2. Logic 3. Philosophy and science 1. Title B105.T54S67 1992 !01-dc20 9136760 1357 986 42 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper For Julia, a woman of fine distinctions Thispage intentionally !efi blank ACKNOWLEDG MENTS This book has indebted me to many people. The first group consists of the individuals who attended colloquia given at the Graduate Center of the City University of New Yo rk, Columbia University, Dartmouth College, Rutgers University, the State University of New Yo rk at Stony Brook, Virginia Tech, and the 1990 lnter-University Conference for Philosophy of Science in Du brovnik. -

20. Implications of Dewey's Pragmatism for Digital

LANCE E. MASON 20. IMPLICATIONS OF DEWEY’S PRAGMATISM FOR DIGITAL MEDIA PEDAGOGY INTRODUCTION The push for ubiquitous digital media technologies in K-12 classrooms has continued unabated for the last generation, with tens of billions of dollars spent in each of the last few years (NCES, 2016). The argument is often made that schools must adjust to the pervasive digitalization of culture, with enthusiastic support from the U.S. Department of Education, along with the Gates Foundation and other powerful (and often self-serving) advocates. In the broader society, the social problems associated with a move to a digital society have become daunting. The 2016 U.S. Presidential election victory of Donald Trump, a savvy media user with no political experience and little coherent ideology, demonstrates the power of new media environments to shape opinions and attitudes, and challenges scholars to reconsider how media alter experiential meaning-making in ways that affect the quality and viability of democracy. While it has been argued that media education (sometimes called media literacy) should be connected to democratic education (see Mason, 2012, 2015; Stoddard, 2014), there is no clear or agreed upon approach to addressing challenges such as fake news and citizen apathy in ways that could bolster participatory democracy enough to challenge to reigning forces of neoliberal capitalism, whose proponents envision the market as the measure of all social value. At present, media presents two broad challenges to citizenship and democratic education. First, the expansion of digital mobile devices has brought media-based entertainment into every corner of contemporary culture. The ready availability of entertainment has affected citizens’ political attitudes, how much time and attention is devoted to political matters and has also contributed to diminished time spent with voluntary associations and other community affairs (Putnam, 2001) that have indirect but profound consequences for democracy in an increasingly image- driven culture. -

Co-Clustering of Directed Graphs Via

The Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-18) CoDiNMF: Co-Clustering of Directed Graphs via NMF Woosang Lim Rundong Du Haesun Park School of Computational Science School of Computational Science School of Computational Science and Engineering and Engineering and Engineering Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia Institute of Technology, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA 30332, USA Atlanta, GA 30332, USA Atlanta, GA 30332, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract co-clustering (Dhillon, Mallela, and Modha 2003), multi- view co-clustering (Sun et al. 2015), co-clustering based Co-clustering computes clusters of data items and the related on spectral approaches (Wu, Benson, and Gleich 2016; features concurrently, and it has been used in many appli- Rohe, Qin, and Yu 2016), co-clustering based on NMF cations such as community detection, product recommenda- tion, computer vision, and pricing optimization. In this paper, (Long, Zhang, and Yu 2005; Wang et al. 2011). However, we propose a new co-clustering method, called CoDiNMF, most of co-clustering methods assume that the connections which improves the clustering quality and finds directional between entities are symmetric or undirected, but many in- patterns among co-clusters by using multiple directed and teractions in real networks are asymmetric or directed. For undirected graphs. We design the objective function of co- example, the data set of patents and words contains a cita- clustering by using min-cut criterion combined with an addi- tion network among patents, and it can be represented as tional term which controls the sum of net directional flow be- a directed and asymmetric graph. -

Re-Construction & Definition of the New Branches of Philosophy

Philosophy Study, June 2016, Vol. 6, No. 6, 305-336 doi: 10.17265/2159-5313/2016.06.001 D DAVID PUBLISHING New Perspective for the Philosophy: Re-Construction & Definition of the New Branches of Philosophy Refet Ramiz Near East University In this article, author evaluated past/present perspectives about philosophy and branches of philosophy due to historical period, religious perspective, and due to their organized categories/branches or areas. Some types of interactions between some disciplines are given as an example. The purpose of this article is, to solve problems related with philosophy and past branches of philosophy, to define new philosophy perspective in the new system, to define new questions and questioning about philosophy or branches of philosophy, to define new or re-constructed branches of philosophy, to define the relations between the philosophy branches, to define good and/or correct structure of philosophy and branches of philosophy, to extend the definition/limits of philosophy, others. Author considered R-Synthesis as a method for the evaluation of the philosophy and related past branches of philosophy. This R-Synthesis includes general/specific perspective with eight categories, 21-dimensions, and twelve general subjects (with related scope and contents) for the past 12,000 years. It is a kind of synthesis of supernaturalism and naturalism, physics and metaphysics, others. In this article, author expressed 27 possible definitive/certain result cases of the new synthesis and defined the possible formation stages to express new theories, new disciplines, theory of interaction, theory of relation, hybrid theory, and others as constructional and/or complementary theories. -

The Literati in Early Western Images of Confucianism

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 13 Number 13 As Others See Us: Mutual Article 15 Perceptions, East and West 1-1-1985 Philosophers as Rulers: The Literati in Early Western Images of Confucianism Edmund Leites Queens College of the City University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Leites, Edmund (1985) "Philosophers as Rulers: The Literati in Early Western Images of Confucianism," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 13 : No. 13 , Article 15. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol13/iss13/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Leites: Philosophers as Rulers: The Literati in Early Western Images of C Philosophers as Rulers The Literati in Early Western Images of Confucianism Edmund Leites In surveying the early Western images of Con- fucianism and the Confucian elite, one is faced with two distinct but related problems: What did Europeans know or believe about Confucianism? How did their beliefs function in their intellectual and, more particularly, philosophical development? I propose to treat both questions in the following pages, although limitations of space prevent my remarks from being more than schematic, sketchy, and suggestive. Europeans owe the formation of their first well-defined image of Con- fucianism (as distinct from an image of China in general) to the Jesuit mission to China. With varying degrees of success, the Jesuits maintained a presence in China, begining with Matteo Ricci's arrival in the 16th century. -

Agricultural Science in Philosophy

Agriculture & Philosophy Agricultural Science in Philosophy Lindsay Falvey TSU Press © Copyright retained by the author. The text words may be copied in any form in context for educational and related purposes. For other purposes, permission should be requested from the author. Title: Agriculture & Philosophy: agricultural science in philosophy / J. Lindsay Falvey (author). Published: Thaksin University Press, 2020. Content Types: Text Subjects: Philosophy & Religion Technology, Engineering, Agriculture. Australian Target Audience: specialized Summary: Agriculture and philosophy have been integrally linked across history and remain so. Philosophy, defined as wise means of humans being at ease in nature, has been fundamental to humans from pre-historical times and expressed in various forms. Those philosophical forms have included myths and legends that explained unfathomable matters to our forebears, and which informed the later development of written philosophy in the form of religious scriptures. Scriptures have thereby been the major written vehicle of philosophy for most of history and across cultures. The language employed in such philosophy relied on agricultural metaphor and used agriculture itself as the means of understanding humans as part of nature, rather than an element standing apart and observing or manipulating. With the development of natural philosophy, which became known as science, it became a major modern contribution to useful knowledge - knowledge that increased contentment and wellbeing, or philosophy. Combining myth, religion, and other knowledge from the world's major cultures, philosophy is discussed using examples from the longest and most widespread human interaction with nature, agriculture. The Enlightenment's philosophical product of agricultural science thus unifies the theme, and supports the ancient conclusion that humans' thoughts and actions form part of nature, and may even be components of a wider interaction than can be comprehended from current approaches. -

The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Faculty and Staff - Articles & Papers Faculty and Staff Summer 2006 The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler Peter J. Colosi Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/fac_staff_pub Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, Other Philosophy Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Colosi, Peter J., "The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler" (2006). Faculty and Staff - Articles & Papers. 64. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/fac_staff_pub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty and Staff - Articles & Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter 3 The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler Peter J. Colosi In a way, his [Pope John Paul II’s] undisputed contribution to Christian thought can be understood as a profound meditation on the person. He enriched and expanded the concept in his encyclicals and other writings. These texts represent a patrimony to be received, collected and assimilated with care.1 - Pope Benedict XVI INTRODUCTION Throughout the writings of Karol Wojtyła, both before and after he became Pope John Paul II, one finds expressions of gratitude and indebtedness to the philosopher Max Scheler.