Parapsychical and Parapsychic Philosophers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ibn Sina (Avicenna)

Neurosurg Focus 11 (2):Article 5, 2001, Click here to return to Table of Contents Ibn Sina (Avicenna) Historical vignette ASITA S. SARRAFZADEH, M.D., NURI SARAFIAN, PH.D., ALMUT VON GLADISS, PH.D., ANDREAS W. UNTERBERG, M.D., PH.D., AND WOLFGANG R. LANKSCH, M.D., PH.D. Department of Neurosurgery, Charité Campus Virchow Medical Center, Humboldt University and Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin, Germany Ibn Sina (often known by his last name in Latin, Avicenna; 980–1037 A.D.) was the most famous physician and phil- osopher of his time. His Canon of Medicine, one of the most famous books in the history of medicine, surveyed the en- tire medical knowledge available from ancient and Muslim sources and provided his own contributions. In this article the authors present a unique picture of the neurosurgical technique of Ibn Sina and briefly summarize his life and work. KEY WORDS • Avicenna • Ibn Sina • historical article HISTORICAL CASE emerged during the disintegration of the Abbasid authori- The Life of Ibn Sina ty. Later he moved to Rayy and then to Hamadan, where he wrote his famous book Al-Qanun fi al-Tibb. Here he Ibn Sina is widely known by his Latin name of Avi- treated Shams al-Dawlah, the King of Hamadan, for se- cenna, although most references to him today have revert- vere colic. From Hamadan, he moved to Isphahan, where ed to the correct version of Ibn Sina, in full Abu 'Ali al- he completed many of his monumental writings. Avicenna Husayn ibn 'Abd Allah Joyce ibn Sina. He was born in wrote 99 books, almost all in Arabic, the language of reli- 980 in Afsana near Bukhara, now Usbekistan, and died in gious and scientific expression in the Muslim world at that 1037 in Hamadan (now Iran). -

Feminist Philosophy

The Blackwell Guide to Feminist Philosophy Edited by Linda Martín Alcoff and Eva Feder Kittay The Blackwell Guide to Feminist Philosophy Blackwell Philosophy Guides Series Editor: Steven M. Cahn, City University of New York Graduate School Written by an international assembly of distinguished philosophers, the Blackwell Philosophy Guides create a groundbreaking student resource – a complete critical survey of the central themes and issues of philosophy today. Focusing and advancing key arguments throughout, each essay incorporates essential background material serving to clarify the history and logic of the relevant topic. Accordingly, these volumes will be a valuable resource for a broad range of students and readers, including professional philosophers. 1 The Blackwell Guide to EPISTEMOLOGY edited by John Greco and Ernest Sosa 2 The Blackwell Guide to ETHICAL THEORY edited by Hugh LaFollette 3 The Blackwell Guide to the MODERN PHILOSOPHERS edited by Steven M. Emmanuel 4 The Blackwell Guide to PHILOSOPHICAL LOGIC edited by Lou Goble 5 The Blackwell Guide to SOCIAL AND POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY edited by Robert L. Simon 6 The Blackwell Guide to BUSINESS ETHICS edited by Norman E. Bowie 7 The Blackwell Guide to the PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE edited by Peter Machamer and Michael Silberstein 8 The Blackwell Guide to METAPHYSICS edited by Richard M. Gale 9 The Blackwell Guide to the PHILOSOPHY OF EDUCATION edited by Nigel Blake, Paul Smeyers, Richard Smith, and Paul Standish 10 The Blackwell Guide to PHILOSOPHY OF MIND edited by Stephen P. Stich and Ted A. Warfi eld 11 The Blackwell Guide to the PHILOSOPHY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES edited by Stephen P. -

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement No. 1/2021 405 IBN SINA IS THE

ASTRA Salvensis, Supplement no. 1/2021 IBN SINA IS THE PINNACLE OF FALSAFA (MUSLIM PHILOSOPHY) Madina K. ZHAKAN1, Raushan N. IMANZHUSSIP1, Aigul O. TURSUNBAYEVA1 1Department of Philosophy, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Nur-Sultan, Republic of Kazakhstan Abstract: This article highlights the philosophical views of Ibn Sina as the most important representative of falsafa. In particular, the article discusses the main problems of falsafa, according to Ibn Sina. These are the problems of a man, his essence, existence, physical and spiritual development. The concept of “wudjud” (being) is the central question in the philosophical teachings of Ibn Sina. According to the philosopher, falsafa studies the being itself then what comes from it. Also, the article discusses questions of space, time, soul, body, and problems of the theory of knowledge in general. The thinker addresses the issue from the standpoint of reason, experience and mysticism. He proceeds from the existence of individual objects of the external world given in experience and then deduces knowledge of natural laws from them. Knowledge of acquaintance is the initial stage of cognition of nature. Ibn Sina analyzes and comprehensively studies the role and power of the sensorium in the process of perception. Keywords: Wudjud, being, possibly-being, necessary-being, essence, causality. It’s known that three main movements, which are Kalam, Falsaf and Sufism, represent the religious and philosophical thought of classical Islam. A rational, philosophical theology of Islam was developed in Kalam. Falsafa is Muslim Aristotelianism (peripateticism) since the primary school of falsafa was composed by the Aristotelians (Peripatetics). Al-Kindi (IX century) is considered to be the founder of falsafa, whose teachings served as a bridge between the Mu’tazilite Kalam and the Muslim school of peripateticism. -

The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler

Chapter 3 The Uniqueness of Persons in the Life and Thought of Karol Wojtyła/Pope John Paul II, with Emphasis on His Indebtedness to Max Scheler Peter J. Colosi In a way, his [Pope John Paul II’s] undisputed contribution to Christian thought can be understood as a profound meditation on the person. He enriched and expanded the concept in his encyclicals and other writings. These texts represent a patrimony to be received, collected and assimilated with care.1 - Pope Benedict XVI INTRODUCTION Throughout the writings of Karol Wojtyła, both before and after he became Pope John Paul II, one finds expressions of gratitude and indebtedness to the philosopher Max Scheler. It is also well known that in his Habilitationsschrift,2 Wojtyła concluded that Max Scheler’s ethical system cannot cohere with Christian ethics. This state of affairs gives rise to the question: which of the ideas of Scheler did Wojtyła embrace and which did he reject? And also, what was Wojtyła’s overall attitude towards and assessment of Scheler? A look through all the works of Wojtyła reveals numerous expressions of gratitude to Scheler for philosophical insights which Wojtyła embraced and built upon, among them this explanation of his sources for The Acting Person, Granted the author’s acquaintance with traditional Aristotelian thought, it is however the work of Max Scheler that has been a major influence upon his reflection. In my overall conception of the person envisaged through the mechanisms of his operative systems and their variations, as presented here, may indeed be seen the Schelerian foundation studied in my previous work.3 I have listed many further examples in the appendix to this paper. -

Avicenna on Beauty

Firenze University Press Aisthesis www.fupress.com/aisthesis Avicenna on Beauty Citation: Mohamadreza Abolghassemi (2018) Avicenna on Beauty. Aisthesis Mohamadreza Abolghassemi 11(1): 45-54. doi: 10.13128/Aisthe- (University of Tehran) sis-23271 [email protected] Copyright: © 2018 Author.This is an open access, peer-reviewed article published by Firenze University Press Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to study the philosophy of Avicenna (980-1073), (http://www.fupress.com/aisthesis) and in order to identify his thoughts and reflections regarding aesthetics. We will try to distribuited under the terms of the analyze several texts in which he treated the notion of beauty. This analysis will allow Creative Commons Attribution License, us to compare the aesthetics of Avicenna with its main origins, namely Aristotelianism which permits unrestricted use, distri- and Neoplatonism. Then, the detailed presentation of his aesthetic reflections will show bution, and reproduction in any medi- us that his contributions to subjects relating to beauty, perfection, and aesthetic delight um, provided the original author and bear some originality which, despite the determining influence of Neoplatonism, has source are credited. its own independent voice. The latter is the case, since these originalities are the results Data Availability Statement: All rel- of a hybridization of two great philosophical schools, namely Aristotelianism and Neo- evant data are within the paper and its platonism. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Avicenna, beauty, perfection, Aristotelianism, Neoplatonism. Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing inter- ests exist. 1. INTRODUCTION This study concerns the philosophy of Ibn Sinâ, one of the phi- losophers, perhaps even the greatest philosopher in the history of Islamic civilization. -

Brief Bibliographic Guide in Medieval Islamic Philosophy and Theology

BRIEF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL GUIDE IN MEDIEVAL AND POST-CLASSICAL ISLAMIC PHILOSOPHY AND THEOLOGY (2014-2015) Thérèse-Anne Druart The Catholic University of America I cannot thank enough all the scholars who kindly sent me information, in particular, those who provided me with a copy of their publications or photocopies of tables of contents of collective works. They are true scholars and true friends. I also wish to thank very much the colleagues who patiently checked the draft of this installment. Their invaluable help was a true work of mercy. Collective Works or Collections of Articles Adamson, Peter, Studies on Early Arabic Philosophy (Variorum). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2015, xii-330 pp., ISBN 9781472420268. -------, Studies on Plotinus and al-Kindî (Variorum). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014, xii-356 pp., ISBN 9781472420251. An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, vol. 5: From the School of Shiraz to the Twentieth Century, ed. by Seyyed Hossein Nasr & Mehdi Aminrazavi. London-New York: I.B. Tauris, 2015, xx-544 pp., ISBN 9781848857506. Aristotle and the Arabic Tradition, ed. by Ahmed Alwishah & Josh Hayes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015, x-270 pp., ISBN 9781107101739. L’averroismo in età moderna (1400-1700), ed. by Giovanni Licata. Macerata: Quodlibet, 2013, 211 pp., ISBN 9788874626465. Controverses sur les écritures canoniques de l’islam, ed. by Daniel De Smet & Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi (Islam – Nouvelles approches). Paris: Cerf, 2014, 436 pp., ISBN 9782204102933. Gutas, Dimitri, Orientations of Avicenna’s Philosophy: Essays on his Life, Method, Heritage (Variorum). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate, 2014, xiv-368 pp., ISBN 9781472436337. The Heritage of Arabo-Islamic Learning. Studies presented to Wadad Kadi, ed. -

PHIL 101.Pdf

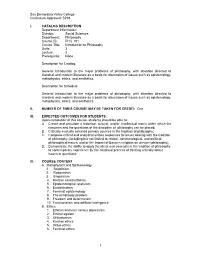

San Bernardino Valley College Curriculum Approved: SP01 I. CATALOG DESCRIPTION Department Information: Division: Social Sciences Department: Philosophy Course ID: PHIL 101 Course Title: Introduction to Philosophy Units: 3 Lecture: 3 Prerequisite: None Description for Catalog: General introduction to the major problems of philosophy, with attention directed to classical and modern literature as a basis for discussion of issues such as epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. Description for Schedule: General introduction to the major problems of philosophy, with attention directed to classical and modern literature as a basis for discussion of issues such as epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aesthetics. II. NUMBER OF TIMES COURSE MAY BE TAKEN FOR CREDIT: One III. EXPECTED OUTCOMES FOR STUDENTS: Upon completion of this course, students should be able to: A. Create and articulate a historical, cultural, and/or intellectual matrix within which the concerns and the questions of the discipline of philosophy can be placed; B. Critically evaluate selected primary sources in the tradition of philosophy; C. Compose critical and analytical written responses to issues dealing with the tradition of philosophy (including but not limited to ethical, epistemological, and political philosophical issues, and/or the impact of Eastern religions on western philosophy); D. Demonstrate the ability to apply the ideas and concepts in the tradition of philosophy to contemporary experience by the continual process of thinking critically about issues or questions IV. COURSE CONTENT A. Metaphysics and Epistemology 1. Skepticism 2. Rationalism 3. Empiricism 4. Kantian constructivism 5. Epistemological relativism 6. Existentialism 7. Feminist epistemology 8. The mind-body problem 9. Freedom and determinism 10. -

Bazi Fikirler Zamanin Ötesindedir Some Ideas Are Beyond Time

BAZI FİKİRLER ZAMANIN ÖTESİNDEDİR SOME IDEAS ARE BEYOND TIME 6 7 C B Küçükten büyüğe doğru sıralanmış kafalar Ay’ın Yörüngesi Güneş Sistemindeki Gezegenler DNA sarmalı Bilimin nesilden nesile gelişim süreci... The Orbit of the Moon Planets of the Solar System DNA’s double-helix A Science’s developmental process from B A C generation to generation in order of the smallest to largest minds... MODERN BİLİMİN ÖNCÜLERİ THE JOURNEY OF THE LOGO OF THE LOGOSUNUN YOLCULUĞU PIONEERS OF MODERN SCIENCE Doğanın geometrisi estetiktir, oranlıdır, ritmik ve Nature’s geometry is aesthetic, proportionate, uyumludur. Bedenimizde saklı ve açık yapılarda; epitel rhythmic, and harmonious. We designed our logo with dokuda, DNA’da, saç telinde, doğada; bir örümcek inspiration from the proportions and movements we ağında, bir arı peteğinde, bitki taç yapraklarında, encounter everywhere: in our bodies, in hidden and ağacın gövdesinde, evrende dev galaksilerde, open structures, in the epithelial tissue, in DNA, in a gezegenlerin yörünge dansında, gök cisimlerinin strand of hair, in the universe, in giant galaxies, in the hareketlerine kadar her yerde karşılaştığımız oran ve dance of the planets’ orbits, even to the motion of KEŞİF / DISCOVER hareketlerden ilhamla tasarladık logomuzu. celestial bodies. Modern bilimin öncüsü bilim insanlarının ilham We turned our gaze to the universe and nature, which GÖZLEM / OBSERVATION kaynağı olan evren ve doğaya bakışlarımızı çevirdik. have been the sources of inspiration for the pioneering Galaksileri oluşturan gezegenlerin sıralanışındaki scientists of modern science. We approached eternity mimari ve geometriye bakarken, sonsuzluğa by looking at the architecture and geometry in the yaklaştık. ordering of the planets that form the galaxies. -

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin

History of Islamic Philosophy Henry Corbin Translated by Liadain Sherrard with the assistance of Philip Sherrard KEGAN PAUL INTERNATIONAL London and New York in association with ISLAMIC PUBLICATIONS for THE INSTITUTE OF ISMAILI STUDIES London The Institute of Ismaili Studies, London The Institute of Ismaili Studies was established in 1977 with the object of promoting scholarship and learning on Islam, in the historical as well as contemporary context, and a better understanding of its relationship with other societies and faiths. The Institute's programmes encourage a perspective which is not confined to the theological and religious heritage of Islam, but seek to explore the relationship of religious ideas to broader dimensions of society and culture. They thus encourage an inter-disciplinary approach to the materials of Islamic history and thought. Particular attention is also given to issues of modernity that arise as Muslims seek to relate their heritage to the contemporary situation. Within the Islamic tradition, the Institute's programmes seek to promote research on those areas which have had relatively lesser attention devoted to them in secondary scholarship to date. These include the intellectual and literary expressions of Shi'ism in general, and Ismailism in particular. In the context of Islamic societies, the Institute's programmes are informed by the full range and diversity of cultures in which Islam is practised today, from the Middle East, Southern and Central Asia and Africa to the industrialized societies of the West, thus taking into consideration the variety of contexts which shape the ideals, beliefs and practices of the faith. The publications facilitated by the Institute will fall into several distinct categories: 1 Occasional papers or essays addressing broad themes of the relationship between religion and society in the historical as well as modern context, with special reference to Islam, but encompassing, where appropriate, other faiths and cultures. -

On the Soul: the Floating Man by Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā), Various Excerpts (~1020-1037 AD)

On the Soul: The Floating Man by Avicenna (Ibn Sīnā), various excerpts (~1020-1037 AD) *** first excerpt from The Psychology of the Book of Healing: On the Soul (Kitab al-Shifa: Tabiyat: ilm al-Nafs) (~1020 AD) translated by John McGinnis & David Reisman (2007) 1.1. Establishing the Existence of the Soul and Defining It As Soul 1. We must first direct our discussion to establishing the existence of the thing we call a soul, and next to whatever follows from that. We say: We commonly observe certain bodies perceiving by the senses and being moved by volition; in fact, we observe certain bodies taking in nutrients, growing, and reproducing their like. That does not belong to them on account of their corporeality; so the remaining option is that in themselves there are principles for that other than their corporeality. The thing out of which these actions issue and, in short, anything that is a principle for the issuance of any actions that do not follow a uniform course devoid of volition, we call “soul.” This expression is a term for this thing not on account of its substance but on account of a certain relation it has, that is, in the sense that it is a principle of these actions [i.e., “perceiving”, “being moved by volition”, “taking in nutrients, growing, and reproducing”, etc.]. We will seek to identify its substance and the category to which it belongs later. For now, we have established the existence of something that is a principle only of what we stated, and we have established the existence of something in the sense that it has a particular accident. -

The Sceptics: the Arguments of the Philosophers

THE SCEPTICS The Arguments of the Philosophers EDITOR: TED HONDERICH The purpose of this series is to provide a contemporary assessment and history of the entire course of philosophical thought. Each book constitutes a detailed, critical introduction to the work of a philosopher of major influence and significance. Plato J.C.B.Gosling Augustine Christopher Kirwan The Presocratic Philosophers Jonathan Barnes Plotinus Lloyd P.Gerson The Sceptics R.J.Hankinson Socrates Gerasimos Xenophon Santas Berkeley George Pitcher Descartes Margaret Dauler Wilson Hobbes Tom Sorell Locke Michael Ayers Spinoza R.J.Delahunty Bentham Ross Harrison Hume Barry Stroud Butler Terence Penelhum John Stuart Mill John Skorupski Thomas Reid Keith Lehrer Kant Ralph C.S.Walker Hegel M.J.Inwood Schopenhauer D.W.Hamlyn Kierkegaard Alastair Hannay Nietzsche Richard Schacht Karl Marx Allen W.Wood Gottlob Frege Hans D.Sluga Meinong Reinhardt Grossmann Husserl David Bell G.E.Moore Thomas Baldwin Wittgenstein Robert J.Fogelin Russell Mark Sainsbury William James Graham Bird Peirce Christopher Hookway Santayana Timothy L.S.Sprigge Dewey J.E.Tiles Bergson A.R.Lacey J.L.Austin G.J.Warnock Karl Popper Anthony O’Hear Ayer John Foster Sartre Peter Caws THE SCEPTICS The Arguments of the Philosophers R.J.Hankinson London and New York For Myles Burnyeat First published 1995 by Routledge First published in paperback 1998 Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1995 R.J.Hankinson All rights reserved. -

An Outline of Philosophy Free

FREE AN OUTLINE OF PHILOSOPHY PDF Bertrand Russell | 352 pages | 06 Apr 2009 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780415473453 | English | London, United Kingdom Outline of philosophy - Wikipedia For younger readers and those with short attention spanshere is my own abbreviated and An Outline of Philosophy history of Western Philosophy, all on one long page. The explanations are necessarily simplistic and lacking in detail, though, and the links should be followed for more information. Thales of Miletus is usually considered the first proper philosopher, although he An Outline of Philosophy just as concerned with natural philosophy what we now call science as with philosophy as we know it. Thales and most of the other Pre-Socratic philosophers i. They were Materialists they believed that all things are composed of material and nothing else and were mainly concerned with trying to establish the single underlying substance the world is made up of a kind of Monismwithout resorting to supernatural or mythological explanations. For instance, Thales thought the whole universe was composed of different forms of water ; Anaximenes concluded it was made of air ; Heraclitus thought it was fire ; and Anaximander some unexplainable substance usually translated as " the infinite " or " the boundless ". Another issue the Pre- Socratics wrestled with was the so-called problem of changehow things appear to change from one form to another. At the extremes, Heraclitus believed in an on-going process of perpetual changea constant interplay of opposites ; Parmenideson the An Outline of Philosophy hand, using a complicated deductive argument, denied that there was any such thing as change at all, and argued that everything that exists is permanentindestructible and unchanging.