Osenseisecrets2, Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Training to Improve Speed Yoshinkan Aikido

STUDIA UBB EDUCATIO ARTIS GYMN., LX, 3, 2015, pp. 53 - 65 (RECOMMENDED CITATION) THE TRAINING TO IMPROVE SPEED YOSHINKAN AIKIDO BOGDAN VASILE, POP ALEXANDRA, BARBOŞ PETRE-ION1* ABSTRACT. Introduction. Aikido, “the way of harmony and love, containing techniques for developing balance, coordination body (joint techniques, throwing, pivot)”. It is approached at early ages, being a branch of sport much favored by children at young ages 6-10 years. This sub-branch of martial arts, due to exoticism, of how it is perceived by the little children produce emulation attracts to practice of a lots of children. On the on the one hand because of the “mysteries” that accompany this sport, on the other hand due to the instructive accompanying it. Among the many branches of martial arts, where some have the tendency more strongly to only focus on technical training, ignoring physical training, other martial arts ignore even preparing locomotor system, to practice safely this art, some even preparing musculoskeletal the practice safely this art. Current Aikido (Aikido Yoshinkan and Takemutsu) maintained in the training program and attaches the utmost importance of physical training: by approaching varied means of physical training for all age levels. Even for young children, a fact demonstrated in the pilot experiment conducted in 2012, the first program launched in Romania in the private school “Happy Kids”, today “Transylvania College, Cambridge International School-Cluj”. This article proposes practitioners a set of athletics exercises in order to strengthen speed, with its forms of expression. By practicing these means of athletic, 2-3 times a week, can obtain high values of this quality (if there is genetic determinations), while in generally, give positive results in improving the biometric qualities, but also the correction of some posts balance or even fighting techniques. -

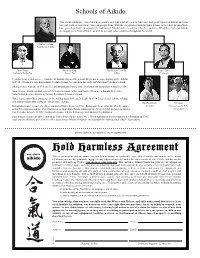

One Circle Hold Harmless Agreement

Schools of Aikido This is not a definitive list of Aikido schools/sensei, but a list of teachers who have had great impact on Aikido and who you will want to read about. You can google them. With the exception of Koichi Tohei Sensei, all teachers pictured here have passed on, but their school/style/tradition of Aikido has been continued by their students. All of these styles of Aikido are taught in the United States, as well as in many other countries throughout the world. Morihei Ueshiba Founder of Aikido Gozo Shioda Morihiro Saito Kisshomaru Ueshiba Koichi Tohei Yoshinkai/Yoshinkan Iwama Ryu Aikikai Ki Society Ueshiba Sensei (Ô-Sensei) … Founder of Aikido. Opened the school which has become known as the Aikikai in 1932. Ô-Sensei’s son, Kisshomaru Ueshiba Sensei, became kancho of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Shioda Sensei was one of Ô-Sensei’s earliest students. Founded the Yoshinkai (or Yoshinkan) school in 1954. Saito Sensei was Head Instructor of Ô-Sensei’s school in the rural town of Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture. Saito Sensei became kancho of Iwama Ryu upon Ô-Sensei’s death. Tohei Sensei was Chief Instructor of the Aikikai upon Ô-Sensei’s death. In 1974 Tohei Sensei left the Aikikai Shin-Shin Toitsu “Ki Society” and founded or Aikido. Rod Kobayashi Bill Sosa Kobayashi Sensei became the direct student of Tohei Sensei in 1961. Kobayashi Sensei was the Chief Lecturer Seidokan International Aikido of Ki Development and the Chief Instructor of Shin-Shin Toitsu Aikido for the Western USA Ki Society (under Association Koichi Tohei Sensei). -

Zenshinkan-Student-Handbook.Pdf

Zenshinkan Center for Japanese Martial, Spiritual,and Cultural Arts Student Handbook ZENSHINKAN DOJO STUDENT HANDBOOK CONTENTS The Way of Transformation .............................................................................................................. 2 Welcome to Zenshinkan Dojo ........................................................................................................... 3 Rules During Practice, Composed by the Founder ........................................................................... 5 Shugyo Policy .................................................................................................................................... 6 Basic Dojo Etiquette .......................................................................................................................... 7 Helpful Words and Phrases .............................................................................................................. 12 A History of Aikido ............................................................................................................................ 15 Zen Training ...................................................................................................................................... 17 For more information On: Our Lineage Test Requirements, Information and Applications Programs, Class Schedules and Upcoming Events Weapons Forms Techniques Zen Training Our website is a rich resource for our dojo’s current activities as well as our history. We also welcome and encourage your -

Libros De Artes Marciales: Guia Bibliografica Comentada"

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTONOMA DEMEXICO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS COLEGIO DE BIBUOTECOLOGIA "LIBROS DE ARTES MARCIALES: GUIA BIBLIOGRAFICA COMENTADA" T E s 1 N A QUE PARA OBTENER EL TITULO DE LICENCIADO EN BIBLIOTECOLOGIA P R E S E N T A JAIME ANAXIMANDRO GUTIERREZ REYES ASESOR: LIC. MIGUEL ANGEL AMAYA RAMIREZ MEXICO, D.F. 2003 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. Agradecimientos: A Shirel Yamile, mi pequeña princesa, a quien adoro. A mis padres, gracias a ellos he podido llegar hasta aquí. A mi asesor, el Licenciado Miguel Ángel Amaya Ramírez, por su guía y consejos. coA mis sinodales, por su ayuda y valiosas observaciones: Lic. Patricia de la Rosa Valgañon Lic. María Teresa González Romero Ing. René Pérez Espinosa Lic. Cesar Augusto RamÍrez Velázquez CONTENIDO INTRODUCCIÓN CAPITULO l. LAS ARTES MARCIALES 1.1 Definición. 1 1.2. Antecedentes. 2 1.3. Tipología 7 1.3.1. Artes marciales practicadas como deporte 7 1.3.2. Artes marciales practicadas como métodos reales de combate 13 1.3.3. -

Youth Handbook.Pub

AIKIDO OF M AINE 2010 THE AOM STUDENT H ANDBOOK F OR C HILDREN AIKIDO OF M AINE 226 Anderson street Portland, Maine 04101 Phone: 207-879-9207 E-mail: [email protected] Www.aikidoofmaine.com Teaching the martial art of peace to adults and children. PAGE 2 AIKIDO OF M AINE PAGE 15 23)P ARKING TABLE OF C ONTENTS Parking is available at the front of the dojo. In addition you can park on street. Please do not park in front of the bakery or block their trucks in 1) Welcome anyway. 2) Mission 3) What is Aikido 24)C AMERAS 4) Description Programs 5) Test process For the safety of our students, AOM reserves the right to use surveillance 6) Stripe achievement program cameras with in the school. Take photos and videos for the website and 7) Making training a priority other promotion. If there is any problem with this please let us know. 8) Web site / Face book 9) Referral and reward program / guess passes 24) GUIDELINES FOR OBSERVERS 10) Dojo 11) Teachers Please keep talking to a minimum or whisper when classes are in session. 12) Terms of Membership Students should have the maximum opportunity to hear the instructor and 13) Dojo events to keep their focus on the mat. Also please do not talk to your child or the instructor during class unless there is an emergency. 14) Dojo Store: dojo dollars, and coupons 15) Dojo Etiquette 16) Your uniform and personal cleanliness 25) READING RECOMENDATIONS 17) Keeping a Healthy dojo 18) Facility and dojo Routine 19) Getting involved For students interested in reading more about Aikido , please see the sug- gested reading list below. -

Aikidohandbook.Pdf

Buseikan Dojo Student Handbook Kyu and Dan Techniques 2015/2016 Base Borden Yoshinkan Aikido Club Introduction Aikido is a modern martial art derived from the Samurai fighting techniques of ancient Japan. Developed during the 1920's, the technical foundations of Aikido can be traced back to Aiki-jujutsu that evolved in early Japan. Aiki-jujutsu techniques were practised by Prince Tejin, son of the Emperor Seiwa (850-880 AD), and passed on to succeeding generations of the Minamoto family. Morihei Ueshiba (1883-1968) became a recognised master of Aiki-jujutsu and several other arts. He also believed in peace. In 1925, he organised a style of Aiki-jujutsu to assist his own spiritual and physical development. The result was Aikido. Aikido is not a conventional fighting art or sport. Instead, it is a martial art that develops the ability to harmonise with opposing forces rather than combat them. Because of this, many circular and spherical movements are involved in Aikido to redirect opposing forces towards a less harmful destination. In Yoshinkan Aikido, the emphasis is on the study of fundamental movements and solid basic techniques as well as gaining philosophical insight into the conduct of life and human relationships. Yoshinkan Aikido as a martial art is non-competitive and non-violent. Co-operation and harmony are more important than aggression. Timing and control are more important than strength. Ueshiba Sensei’s top student was Gozo Shioda (1915-1994). In 1955, after receiving 9th Dan, Gozo Shioda Sensei formed the Aikido Yoshinkan Foundation. Shioda Sensei's style of Aikido is known as Yoshinkan, a name that he inherited from his father. -

Aikido Framingham Aikikai, Inc

Aikido Framingham Aikikai, Inc. 61 Fountain Street Framingham, MA 01701 (508) 626-3660 www.aikidoframingham.com Framingham Aikikai Information on Aikido Practice and Etiquette Welcome to Framingham Aikikai History Instructors and Certification Consistency of Technique Testing & Promotions Attendance Status & Fees Dojo Cleanliness Personal Cleanliness Logistical Information Etiquette Important Points About Aikido Practice (on the mat) Things to Keep in Mind As You Begin Aikido Practice Basic Concepts Iaido Japanese Terms Used in Aikido: USAF Test Requirements 1 Welcome to Framingham Aikikai! This document is intended to provide background and basic information and to address questions a new student of Aikido may to have. Aikido practice is fascinating but challenging. As a beginner, your main objective should be to get yourself onto the mat with some regularity. Beyond that, just relax, enjoy practicing and learning, and let Aikido unfold at its own pace. The instructors and your fellow students are resources that will provide you with continuing support. Don’t hesitate to ask questions or let them know if you need help or information. Feel free at any time to talk to the Chief Instructor at the dojo, on the phone or via email at [email protected]. History, Lineage & Affiliations Framingham Aikikai (FA) was founded in January 2000 by David Halprin, who studied for over twentyfive years as a student of Kanai Sensei at New England Aikikai in Cambridge. FA is a member dojo of the United States Aikido Federation (USAF). The USAF was founded in the 1960's by Yoshimitsu Yamada, 8th Dan, of New York Aikikai, and Mitsunari Kanai, 8th Dan, of New England Aikikai. -

1993 December

AIKIDO YOSFIINKAIU INTERNATIONAL Vol.4 No.3 DECEMBER ]993 1 YA F lqcnrviro\Al. yossrNKAr Alrrr(l ! ll)lrtAi roN K. .L.12 N fr& Anhffi,Hflm toYcr;hiril<m Nkih YOSHINIiAN A11llT)O l'IDLO ll iiriuirrrr rtrtr,tr ltoro tz IYAF First Step IYAF Second SteP Ersish 34m n U.S $33 i Ens ish 47mln U.S. $38 I I :i YOSHINKA\ AIKIDO \iIDDo I THE WAY OF AIKIDO TECHNIQUES ,LE VRAI ET PURE AIKIDO'' 60mn U.S $69 FF400 YOSHINIIAN l\1KIT]O VIDEO 2 DEI\,IONSTRATION OF i,;rii-....r., L-r.n 'P;i ", - IUOST ADVANCED TECHNIQUES ,DEI\,4ONSTRATION DES TECHNIQUES'' 3Omn U.S $50 FF330 IOSHINXAN -\IKII]O VIDEO N FIRST INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION OF YOSHINMNAIKIDO - June 23, 1990.Tororto ontario. Canada 89n n U.s $ 60 CAN $ 65 i E',!r sr -ar*rrn^t oro,uo,rr,nu , YOSHINI{AN AllilDO XIDEO 10 #|t'i;i SOKE GOZO SHIODA SENSEIS SOKE GOZO SHIODA SENSEIS VISIT TO TORONTO, CANADA VISIT TO WINDSOR, CANADA Enlilnll 23min. U S $ 33 li Ers !h 46hi.. US $43 li AIKIDO YOSHINKAN INTERNATIONAL Vol. 4 No. 3 December 1993 (n,o Publish.r: shrodd O 1993 AIKIDO YOSHI\KA\ liditor: Hlrost'i NLLkano sr!ff: tron,ar.lBi.ndl 2 2E,8. Kanriochiai. Shl! !k! I!. Tokyo 161. J.pan Cofespondrnts: J.cques Payer Tel:81(i)l)l-1685556 |-ax: 81 (01) -1368 5518 lamcs Jcamctr. All rights rcsrrlcd Rohcrt NIunad Corer: Callleraphy. "Aikldo Yoshi.knn. bl \or. pame a Hunt Vark Baker Go/o Shiod, l,:l',;; .im U..n r1,. -

Aikido and Spirituality: Japanese Religious Influences in a Martial Art

Durham E-Theses Aikid©oand spirituality: Japanese religious inuences in a martial art Greenhalgh, Margaret How to cite: Greenhalgh, Margaret (2003) Aikid©oand spirituality: Japanese religious inuences in a martial art, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4081/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk AIK3DO AND SPIRITUALITY: JAPANESE RELIGIOUS INFLUENCES IN A MARTIAL _ ART A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts in East Asian Studies in the Department of East Asian Studies University of Durham Margaret Greenhalgh December 2003 AUG 2004 COPYRIGHT The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it may be published without her prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Aikido Framingham Aikikai, Inc

Aikido Framingham Aikikai, Inc. 26 Summer Street Natick, MA 01701 (508) 626-3660 www.aikidoframingham.com Framingham Aikikai Information on Aikido Practice and Etiquette Welcome to Framingham Aikikai!....................................................................................... 2 History, Lineage & Affiliations............................................................................................. 2 Instructors and Certification ............................................................................................... 3 Consistency of Technique ................................................................................................... 4 Testing & Promotions ......................................................................................................... 4 Attendance .......................................................................................................................... 6 Status & Fees ...................................................................................................................... 6 Dojo Cleanliness .................................................................................................................. 7 Personal Cleanliness ........................................................................................................... 8 Logistical Information ......................................................................................................... 9 Etiquette .......................................................................................................................... -

Japanese Phrases That Are Used in the Dojo

Welcome to Prairie Winds Aikido. We are so glad that you are giving Aikido a try! Whether this is your first martial art or you have been practicing for years, Aikido will meet you where you are at. Each art has its own peculiar characteristics. Aikido (the way we practice it) is traditional and non- competitive. There are no competitions. There are only two belts, white and black. In Aikido, advanced ranks also wear a black skirt-like garment called a hakama. We spend a lot of our time learning to counteract several types of attacks…usually this involves putting an attacker in a joint lock and then throwing him/her. So, we spend a lot of our time learning how to fall properly. The act of throwing and being thrown both teach us valuable lessons about how our bodies work. We learn several different joint locks. We talk a lot about blending and harmonizing so that these movements become effortless. Aikido is not about who is strongest. We do not spend a lot of time learning how to punch or kick. So, that may seem different from other arts. We do spend a lot of time learning how to get out of the way of a punch or kick. We also spend time learning about traditional weapons, like the wooden sword (called a bokken) and a short staff (called a jo). We do this to improve our posture, and our character. It is really hard to cut a sword in a perfect line, but by practicing a “simple” cut, we are reminded that we can learn a lot from something seemingly simple. -

Garry Masters 8Th Dan Principal Coach Kenshinkai Aikido UK

Garry Masters 8th Dan Principal Coach Kenshinkai Aikido UK 8th Dan Principal Coach - Kenshinkai Aikido 8th Dan Instructor - Yoshinkan Aikido 1st Dan - Jodo & Iaido Garry began practising Yoshinkan Aikido in Portsmouth, UK in 1978 under the tuition of Sensei David Eayrs (founder of Kenshinkai and a founder member of the British Aikido Board). Garry had been advised by his doctor that due to a congenital heart defect he should avoid sport and physical exercise. Garry explained this to David who replied that he thought Aikido would be good for his health and encouraged him to join the club, which at that time was part of the UK Shudokan Institute of Aikido organisation run by Sensei Ted Stratton (later to separate from the Shudokan and become Kenshinkai in 1985). Garry was Chief Instructor of Kenshinkai from 1985 until 1994, also gaining experience in Iaido, Shoto, Jodo and Tanjo, winning the first ever Jodo championship held in England (Mudan Section) in 1986. In 1994 after David left the UK to establish Yoshinkan Aikido in Moscow, Garry was elected as Principal Coach & Chairman of Kenshinkai. In his time as Principal Coach, Garry obtained International recognition for Kenshinkai by re-establishing it as an Independent Yoshinkan Aikido Organisation, recognised by the Aikido Yoshinkan Federation (AYF), the headquarters for Yoshinkan Aikido based in Japan. Over the years Garry has accumulated an extensive knowledge of Yoshinkan and various other styles of Aikido, receiving additional tuition from Francis Ramasamy (David Eayrs first instructor in Malaysia) and attending seminars taught by Kiyoyuki Terada, Morihiro Saito, Tsuneo Ando, Kyoichi Inoue, Tsutomu Chida, Takefumi Takeno, Yasuhisa Shioda among others.