Chernobyl and Its Political Fallout: a Reassessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the European Union Promotes Democracy Through Membership Conditionality Ryan Phillips

Why the European Union Promotes Democracy through Membership Conditionality Ryan Phillips Government & International Relations Department, Connecticut College, 270 Mohegan Avenue, New London, CT 06320, USA, E-mail: [email protected] Prepared for 2017 EUSA Conference – Miami, FL DO NOT CITE OR CIRCULATE Abstract Explanations of why the European Union promotes democracy through membership conditionality provide different accounts of its normative rationale. Constructivists argue that the EU’s membership policy reflects a norm-driven commitment to democracy as fundamental to political legitimacy. Alternatively, rationalists argue that membership conditionality is a way for member states to advance their economic and security interests in the near abroad. The existing research, however, has only a weak empirical basis. A systematic consideration of evidence leads to a novel understanding of EU membership conditionality. The main empirical finding is that whereas the constructivist argument holds true when de facto membership criteria were first established in the 1960s, the rationalist argument more closely aligns with the evidence at the end of the Cold War when accession requirements were formally codified as part of the Copenhagen Criteria (1993). Keywords: democracy promotion, political conditionality, enlargement, European Union, membership Word Count: 7177 1 Introduction On October 12, 2012 in the Norwegian capital of Oslo, Thorbjørn Jagland declared, ‘The Norwegian Nobel Committee has decided that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2012 is to be awarded to the European Union. The Union and its forerunners have for over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe’ (Jagland 2012). In awarding the EU the Nobel Peace Prize, the former prime minister voiced a common view of the organization as well as its predecessors, namely that it has been a major force for the advancement of democracy throughout Europe. -

NORMAN A. GRAEBNER (Charlottesville, VA, U.S.A.)

NORMAN A. GRAEBNER (Charlottesville, VA, U.S.A.) GORBACHEV AND REAGAN Outside Geneva's Chateau Fleur d'Eau on a wintry 19 November 1985, a coatless Ronald Reagan awaited the ap- proaching Mikhail Gorbachev. The American President, as the official host of this first day of the Geneva summit, had set the stage for his first meeting with the Soviet leader with great care. He led Gorbachev and their two interpreters to a small meeting room with a fire crackling in the fireplace for a pri- vate conversation. The people in the neighboring conference room, Reagan began, had given them 15 minutes "to meet in this one-on-one.... They've programmed us-they've written your talking points, they've written my talking points. We can do that, or we can stay here as long as we want and get to know each other...." The private conversation lasted an hour. During a break in the afternoon session Reagan steered Gorbachev to the chateau's summerhouse for a tete-a-tete before the fire. At the end the two leaders achieved little, yet both re- garded the summit a success. Separated by twenty years, they recognized in each other a warmth and sincerity that promised future success. Reagan observed that Gorbachev scarcely re- sembled his predecessors in his intelligence, knowledge and openness. Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze noted, "[W]e had the impression that [the President] is a man who keeps his word and that he's someone you can deal with ... and reach accord." The two leaders, pursuing complementary agendas, had approached the Geneva summit along highly' dis- similar paths. -

Diplomatic Negotiations and the Portrayal of Détente in Pravda, 1972-75

A Personal Affair : Diplomatic Negotiations and the Portrayal of Détente in Pravda, 1972-75 Michael V. Paulauskas A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Donald J. Raleigh Reader: David Griffiths Reader: Chad Bryant ABSTRACT MICHAEL V. PAULAUSKAS: A Personal Affair: Diplomatic Negotiations and the Portrayal of Détente in Pravda, 1972-75 (Under the direction of Donald J. Raleigh) This thesis explores how diplomatic relations between the US and the USSR changed during détente , specifically concentrating on the period between the 1972 Moscow Summit and the enactment of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment to the 1974 Trade Bill . I employ transcripts of diplomatic negotiations to investigate the ways that Soviet and American leaders used new personal relationships with their adversaries to achieve thei r foreign policy goals. In order to gain further understanding of the Soviet leadership’s attitudes toward détente, I also examine how the Soviet government, through Pravda, communicated this new, increasingly complex diplomatic relationship to the Soviet public in a nuanced fashion, with multilayered presentations of American foreign policy that included portrayals of individual actors and not simply impersonal groups . ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………..…………………………………………. 1 A Cautious Beginning: Soviet -American Relations before the Moscow Summit ..…………...9 The Lifting of the Veil: The 1972 Moscow Summit …………………………..…………….16 The High -Water Mark of Détente: The 1973 US Summit …..………………………….……30 “Nixon’s Last Friend”: The Watergate Scandal …………………………………………..…37 Détente in Crisis: The Jackson-Vanik Amendment ……………..…………………………..45 Conclusion…………………………………………………..……………………………….53 Appendices ……………………………………………..……………………………………57 Bibliography …………………………………………..……………………………………..65 iii Introduction Soviet Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin greeted the news of Richard M. -

Huron University College Department of English English 2550F: Heroes

Huron University College Department of English English 2550F: Heroes and Superheroes Intersession 2021 Dr. Adrian Mioc Class: Tue 9:30 AM -12:30 PM, Th 9:30 AM - 12:30 PM Office: UC 3314 Office Hours: Thu 12:30-2:30 PM Email: [email protected] Prerequisite(s): At least 60% in 1.0 of English 1020-1999 or permission of the Department. Although this academic year might be different, Huron University is committed to a thriving campus. We encourage you to check out the Digital Student Experience website to manage your academics and well-being. Additionally, the following link provides available resources to support students on and off campus: https://www.uwo.ca/health/. Technical Requirements: Stable internet connection Laptop or computer Working microphone Working webcam General Course Description This course aims to explore the figure of the hero and superhero as it evolves and is depicted in contemporary comic books as well as in other forms of popular culture such as movies and TV series. Methodologically, it will combine the study of literature with contemporary popular culture while incorporating a theoretical component as well. Specific Focus: In the beginning, we will briefly explore myths that are relevant and will help us understand the figure of the modern day superhero. After a quick historical exploration, which will offer a substantial foundation for the study of the 20th and 21st-century manifestation of the superheroes, the main focus of this course will be placed on the problematic of this figure. Besides well-known characters (Superman, Batman and Spiderman), we will tackle less-spoken-about figures such as Jessica Jones or Harley Qinn. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1990

ublished by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-profit association rainian Weekly vol. LVIII No. 12 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 25,1990 50 cents 1 million in Ukraine Democratic Bloc scores impressive victories in run-offs suffer in aftermath of Chernobyl by Dr. David Mar pies in mid-February, the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR held an impor– tant meeting on the ecological situation in Ukraine. That the focus of this meeting was largely devoted to the effects of Chornobyl was hardly sur– prising given some of the recent revela– tions about the long-term effects of that disaster. Also, it followed closely upon the publication of a "Complex Program for the Liquidation of the Consequences of the Accident of Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant in the Ukrainian SSR"one week earlier. At the Supreme Soviet meeting, there were comments from both the propo– nents of nuclear power and the op– ponents, with the latter constituting a clear majority. While much bitterness was exhibited, along with calls for retribution against certain individuals, there were at the same time several positive suggestions that reflected a Flags of various nationalities wave at pre-election rally in Kiev, more open debate on this topic. Preliminary results further impressive victories in the Ukrainian Helsinki Union and other The tone of the Supreme Soviet Sunday, March 18, run-off elections, independent groups) are reported to meeting was set by a remarkably candid give 25 percent to DB reported Radio Liberty's Ukrainian have won 15 out of the 21 contested speech by Yuriy Spizhenko, the Ukrai– in Ukrainian Parliament desk on Monday, March 19. -

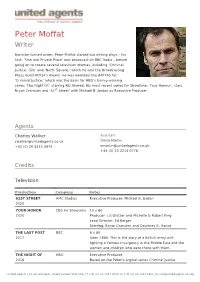

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Television and Politics in the Soviet Union by Ellen Mickiewicz TELEVISION and AMERICA's CHILDREN a Crisis of Neglect by Edward L

SPLIT SIGNALS COMMUNICATION AND SOCIETY edited by George Gerbner and Marsha Seifert IMAGE ETHICS The Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Film, and Television Edited by Larry Gross, John Stuart Katz, and Jay Ruby CENSORSHIP The Knot That Binds Power and Knowledge By Sue Curry Jansen SPLIT SIGNALS Television and Politics in the Soviet Union By Ellen Mickiewicz TELEVISION AND AMERICA'S CHILDREN A Crisis of Neglect By Edward L. Palmer SPLIT SIGNALS Television and Politics in the Soviet Union ELLEN MICKIEWICZ New York Oxford OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1988 Oxford University Press Oxford New York Toronto Delhi Bombay Calcutta Madras Karachi Petaling Jaya Singapore Hong Kong Tokyo Nairobi Dar es Salaam Cape Town Melbourne Auckland and associated companies in Berlin Ibadan Copyright © 1988 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 200 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of Oxford University Press. Mickiewicz, Ellen Propper. Split signals : television and politics in the Soviet Union / Ellen Mickiewicz. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-19-505463-6 1. Television broadcasting of news—Soviet Union. 2. Television broadcasting—Social aspects—Soviet Union. 3. Television broadcasting—Political aspects—Soviet Union. 4. Soviet Union— Politics and government—1982- I. Title. PN5277.T4M53 1988 302.2'345'0947—dc!9 88-4200 CIP 1098 7654321 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Preface In television terminology, broadcast signals are split when they are divided and sent to two or more locations simultaneously. -

The Security of the Caspian Sea Region

16. The Georgian–Abkhazian conflict Alexander Krylov I. Introduction The Abkhaz have long populated the western Caucasus. They currently number about 100 000 people, speak one of the languages of the Abkhazo-Adygeyan (west Caucasian) language group, and live in the coastal areas on the southern slopes of the Caucasian ridge and along the Black Sea coast. Together with closely related peoples of the western Caucasus (for example, the Abazins, Adygeyans and Kabardians (or Circassians)) they play an important role in the Caucasian ethno-cultural community and consider themselves an integral part of its future. At the same time, the people living in coastal areas on the southern slopes of the Caucasian ridge have achieved broader communication with Asia Minor and the Mediterranean civilizations than any other people of the Caucasus. The geographical position of Abkhazia on the Black Sea coast has made its people a major factor in the historical process of the western Caucasus, acting as an economic and cultural bridge with the outside world. Georgians and Abkhaz have been neighbours from time immemorial. The Georgians currently number about 4 million people. The process of national consolidation of the Georgian nation is still far from complete: it includes some 20 subgroups, and the Megrelians (sometimes called Mingrelians) and Svans who live in western Georgia are so different in language and culture from other Georgians that it would be more correct to consider them as separate peoples. Some scholars, Hewitt, for example,1 suggest calling the Georgian nation not ‘Georgians’ but by their own name, Kartvelians, which includes the Georgians, Megrelians and Svans.2 To call all the different Kartvelian groups ‘Georgians’ obscures the true ethnic situation. -

The South Caucasus: Where the Us and Turkey Succeeded Together

THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: WHERE THE US AND TURKEY SUCCEEDED TOGETHER As Americans and Turks discuss the ups and downs in their relationship, the strategically important South Caucasus is one area, where, working together, Turkey and the United States have helped bring about historic changes. More can be done to realize the region’s promise should the US and Turkey deepen their partnership with Azerbaijan and Georgia and build on the policies that have proven to be successful. This success has been based on forward-looking pragmatism and recognition of common interests. Acknowledging the achievements in the South Caucasus and learning from them can contribute to future progress in the US-Turkey relationship. Elin Suleymanov∗ ∗ Elin Suleymanov is Senior Counselor with the Government of Azerbaijan. The views and opinions are his own and do not imply an endorsement by the employer. ormerly a Soviet backyard, the South Caucasus is increasingly emerging as a vital part of the extended European space. Sandwiched between the Black and the Caspian seas, the Caucasus F also stands as a key juncture of Eurasia. Living up to its historic reputation, the South Caucasus, especially the Republic of Azerbaijan, is now literally at the crossroads of the East-West and North – South transport corridors. Additionally, the Caucasus has been included concurrently into a rather vague “European Neighborhood” and an even vaguer “Greater Middle East.” This represents both the world’s growing realization of the region’s importance and the lack of a clear immediate plan to address the rising significance of the Caucasus. Not that the Caucasus has lacked visionaries. -

TV Academy Honors ARRI ALEXA Camera System with Engineering Emmy®

Contact: An Tran Public Relations Manager + 1 818 841 7070 [email protected] Reegan Koester Corporate Communications Manager +49 89 3809 1768 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE TV Academy Honors ARRI ALEXA Camera System with Engineering Emmy® • ARRI receives highest TV technology recognition for outstanding achievement in engineering development • Since 2010, ALEXA has been the camera system of choice on numerous television and feature productions • ALEXA’s digital technology has been embraced by the television industry for its stunning image quality, reliability, and ease October 26, 2017, Los Angeles – At the 69th Engineering Emmy® Awards Ceremony in Hollywood, the Television Academy recognized ARRI with the most prestigious television accolade for outstanding achievement in engineering development for its ALEXA digital motion picture camera system. On October 25, 2017, at the Loews Hollywood Hotel, actress Kirsten Vangsness, who presented the award, said: “The ALEXA camera system represents a transformative technology in television due to its excellent digital imaging capabilities coupled with a completely integrated postproduction workflow. In addition, a cohesive pipeline, the onboard recording of both raw and a compressed video image, and an easy-to-use interface contributed to the television industry’s widespread adoption of the ARRI ALEXA.” The Engineering Award was accepted by ARRI´s Harald Brendel, Teamlead Image Science, and Frank Zeidler, Senior Manager Technology and Deputy Head of R&D – both members of the ALEXA development team – as well as Glenn Kennel, President of ARRI Inc. In his acceptance speech, Harald Brendel mentioned ARRI’s 100-year legacy of laying the foundation for the ALEXA and keeping the camera today as the industry workhorse. -

Reform and Human Rights the Gorbachev Record

100TH-CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES [ 1023 REFORM AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE GORBACHEV RECORD REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES BY THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MAY 1988 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1988 84-979 = For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE STENY H. HOYER, Maryland, Chairman DENNIS DeCONCINI, Arizona, Cochairman DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts TIMOTHY WIRTH, Colorado BILL RICHARDSON, New Mexico WYCHE FOWLER, Georgia EDWARD FEIGHAN, Ohio HARRY REED, Nevada DON RITTER, Pennslyvania ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JACK F. KEMP, New York JAMES McCLURE, Idaho JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming EXECUTIvR BRANCH HON. RICHARD SCHIFIER, Department of State Vacancy, Department of Defense Vacancy, Department of Commerce Samuel G. Wise, Staff Director Mary Sue Hafner, Deputy Staff Director and General Counsel Jane S. Fisher, Senior Staff Consultant Michael Amitay, Staff Assistant Catherine Cosman, Staff Assistant Orest Deychakiwsky, Staff Assistant Josh Dorosin, Staff Assistant John Finerty, Staff Assistant Robert Hand, Staff Assistant Gina M. Harner, Administrative Assistant Judy Ingram, Staff Assistant Jesse L. Jacobs, Staff Assistant Judi Kerns, Ofrice Manager Ronald McNamara, Staff Assistant Michael Ochs, Staff Assistant Spencer Oliver, Consultant Erika B. Schlager, Staff Assistant Thomas Warner, Pinting Clerk (11) CONTENTS Page Summary Letter of Transmittal .................... V........................................V Reform and Human Rights: The Gorbachev Record ................................................ -

The Red Scare- Soviet Union

JCC: The Red Scare- Soviet Union Chair: Bridget Arnold Vice-Chair: 1 Table of Contents 3. Letter from Chair 4. Committee Background 7. Topic A: Race to the Moon 15. Topic B: Developing Tensions is the West 24. Positions 2 Letter from the Chair: Dear Fellow Comrades, Hello, and welcome to LYMUN VII! I am extremely excited to be chairing (the better side) of the JCC: The Red Scare. My name is Bridget Arnold, I am currently a Senior at Lyons Township and I have participated in Model UN since my Freshman year. Outside of MUN, I participate in various clubs such as Mock Trial and PSI and in general have a huge fascination with politics. In anticipation of the conference, you are expected to write one position paper outlining your person’s beliefs on the topics that you have been given. Both topics will be discussed in order but only one position paper is required. All delegates should maintain their character’s policy within the committee and should avoid slipping into their own personal beliefs. During committee, I will not only be looking for delegates who speak a lot but those who work well with other delegates, contribute to discussions, and exemplify knowledge about the topic in their speeches. With that being said, I encourage all delegates to speak at least once in this committee. Any experience with public speaking will benefit your skills as a public speaker now and in the future. Writing directives and crisis notes with your own original ideas are also crucial for success in this cabinet.