PHENOMENAL LITERATURE a Global Journal Devoted to Language and Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

Teaching Plan B.A. I 2016-17

Jaywant Pratishthan Humgaon Sanchalit Amdar Shashikant Shinde Mahvidyalay, Medha Department of English Teaching Plan B.A. I 2016-17 Sr. Month Paper Topic No. June Comp. Introduction to the syllabus and evaluation pattern Sentence Construction Paper I Introduction to the syllabus and evaluation pattern Introduction to literature July Comp. Sentence Construction Talking about persons, Objects and Places Describing Daily Routine Paper I Short Stories in English Characteristics of Short Story The Home Coming August Comp. The Runner A Frog Screams Grass Words Paper I The Cherry Tree Mr. Know-All September Comp. In Sahyadri Hills: a lesson in Humility The Bougainvillea Paper I The Refugee The Lumber Room October Comp. Narrating Experiences Revision Paper I Revision November Comp. Examinations Paper I December Comp. Application letter and C.V. The Final Decision Paper II Introduction to Novel as a Form of Literature Characteristics of Novel Lord of the Flies: Introduction , Chapters I, II January Comp. Writing News Reports My Education The Snake Trying Paper II Lord of the Flies- Chapters III, IV, V, VI, VII February Comp. Making Enquiries and Giving Instructions The Boy Comes Home Again Telephonic Conversation Paper II Lord of the Flies- Chapters VIII, IX, X, XI, XII March Comp. Revision Paper II Lord of the Flies Revision Subject Teacher Head Principal Jaywant Pratishthan Humgaon Sanchalit Amdar Shashikant Shinde Mahavidyalay, Medha Department of English Teaching Plan B.A. II 2016-17 Month Paper Topic June Comp Section I: Communication Skills Expressing Likes/Dislikes/Beliefs/Opinions Paper III Types of poems Paper IV Novel background July Comp Drafting Formal Notices Paper III G. -

Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210

ISSN-L 0537-1988 UGC Approved Journal (Journal Number 46467, Sl. No. 228) (Valid till May 2018. All papers published in it were accepted before that date) Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210 56 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Vol. LVI 2019 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The responsibility for facts stated, opinions expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any in this journal, is entirely that of the author(s). The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA 56 2019 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES) published since 1940 accepts scholarly papers presented by the AESI members at the annual conferences of Association for English Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the copies of journal for home, college, university/departmental library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri by sending an e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are requested to place orders on behalf of their institutions for one or more copies. Orders by post can be sent to the Editor- in-Chief, Indian Journal of English Studies, Anand Math, Near St. Paul School, Harnichak, Anisabad, Patna-800002 (Bihar) India. ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA Price: ``` 350 (for individuals) ``` 600 (for institutions) £ 10 (for overseas) Submission Guidelines Papers presented at AESI (Association for English Studies of India) annual conference are given due consideration, the journal also welcomes outstanding articles/research papers from faculty members, scholars and writers. -

Gurumoviedownloadinutorrent.Pdf

1 / 2 Gurumoviedownloadinutorrent Watch The Guru (2002) online full movie, free torrent streaming now. South Asian Ramu Gupta has always ... Direct Download. Server 02. Torrent Download .... Movie Plot: A villager, Gurukant Desai, arrives in Bombay 1958, and rises from its streets to become the GURU, the biggest tycoon in Indian .... Since uTorrent is by far the most popular client both for Windows and Mac, we have ... Download a smaller version of the movie or music album.. Guru of 3D: Computer PC Hardware and Consumer Electronics reviews. ... It sounds like a movie trailer; but the trilogy ends today, the 3rd iteration SKU of AMD .... P2P Guru believes that torrent sites need to do better, and that's why they offer a considerably better user-experience, as well as top privacy and .... 1337x is the new 13377x 2020 torrent web site to download latest hd movies, ... dvadsiateho storočia svetoznámy indický guru, ktorý žil to, čo hovoril a hovoril to, .... download The Love Guru movie, The Love Guru download subtitles, The ... Love Guru full movie download utorrent, download The Love Guru, .... Chalat Musafir Moh Liyo Re Full Movie Download In Dual Audio English Hindi. ... flexyjams cdq Fakaza download datafilehost torrent download Song Below. ... you know that Guru was very important to me, since his album Jazzmatazz vol.. Heyy Babyy dual audio eng hindi 720p download in kickass torrent. ... Chal Guru Ho Ja Shuru man 2 full movie in hindi download utorrent .... Raees Full Movie Download 2017 Hindi 720p & 480p Blu-Ray Full HD. Raees Full ... Kom Perfect Plan tamil full movie hd 1080p blu-ray download torrent. -

Unit 17 General Introduction to the Indian English Novel

UNIT 17 GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE INDIAN ENGLISH NOVEL Structure 17.0 Objectives 17.1 Introduction 17.2 What is a Novel? 17.3 Aspects of the Novel. 17.3.1 Theme 17.3.2 Plot 17.3.3 Characterization 17.3.4 Point of View 17.3.5 Place and Time 17.3.6 Narration or Dramatization 17.3.7 Style 17.4 Types of Novels 17.4.1 Picaresque Novel$ 17.4.2 Gothic Novel 17.4.3 Epistolary Novel 17.4.4 Psychological Novel 17.4.5 Historical Novel 17.4.6 Regional Novel 17.4.7 Other typeslforms 17.5 The Rise of the Indian Novel in English 17.5.1 The Beginning 17.5.2 The Novel in the early 20* Century 17.5.3 Women's Writing 17.6 Shashi Deshpande 17.6.1 Shashi Deshpande as a Novelist 17.7 Glossary 17.8 Let Us Sum Up 17.9 Suggested Reading . 17.10 Answers to Exercises 17.0 OBJECTIVES The aim of this unit is to introduce you to the genre of the novel and trace its aspects. We also aim to familiarize you with the rise of the Indian novel in English. After studying this unit carefully and completing the exercises, you will be able to : outline the development of the novel and its types recognize its different aspects know the history of the Indian novel in English, and trace its development. 17.1 INTRODUCTION In this Block, we intend to introduce you to the genre of the novel, with special reference to Shashi Deshpande's The Binding Vine, prescribed in your course. -

Conclusion the Study of 'Construction and Contestation of Nation in Indian

Conclusion The study of 'Construction and Contestation of Nation in Indian English Fiction' was undertaken with the purpose of understanding the notion of nation underlying the texts and the alternative collectivity imagined therein. It has been carried out in this study by attending to three dimensions: the construction of collective identity, contestations of hegemonic construction of collective identity and visions of collective identities beyond the nation. Novels studied are all canonical texts and this selection was intended to enable a perspective into the 'mainstream' approaches to the issue of nations and nationalisms. The study does not present a detailed analysis of the novels in relation to the various content or form related aspects of the novel. For example, it does not enter into the exercise of exploring the psychological make up of characters, or the examination of the language used by the authors. Such and other investigations are employed in the study only in so far as they have a bearing on the issue under consideration. The idea behind restricting the scope is to keep the focus firmly on the issue being pursued. Three frameworks are adopted for the study. These frameworks are aimed at enabling a view of the notion of nation emerging at different historical junctures and in relation to various developments. However, the selection of novels for study under each framework is guided not by their year of publication or writing but by the period the stories relate to. As a result, while the novels discussed in each chapter have been published at various dates, they all concern themselves with roughly the same historical period. -

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K. Singh Literary Criticism Z Realism in the Romances of Shakespeare Z Dynamics of Poetry in Fiction Z The Creative Contours of Ruskin Bond (ed.) Z A Passage to Shiv K. Kumar Z The Indian English Novel Today (ed.) Poetry Z So Many Crosses Z The Vermilion Moon Z In the Olive Green Z Lamhe (Hindi) Translation into Hindi Z Raat Ke Ajnabi: Do Laghu Upanyasa (Two novellas of Ruskin Bond – A Handful of Nuts and The Sensualist) Z Mahabharat: Ek Naveen Rupantar (Shiv K. Kumar’s The Mahabharata) The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Edited by Prabhat K. Singh The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium, Edited by Prabhat K. Singh This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Prabhat K. Singh All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4951-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4951-7 For the lovers of the Indian English novel CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 The Narrative Strands in the Indian English Novel: Needs, Desires and Directions Prabhat K. Singh Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 28 Performance and Promise in the Indian Novel in English Gour Kishore Das Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Telugu Dubbed Lingaa Full Movie

Telugu Dubbed Lingaa Full Movie Telugu Dubbed Lingaa Full Movie 1 / 5 2 / 5 KuttyMovies, KuttyMovies Movies Download, KuttyMovies New Movies Download. ... 2017 Movies. [+] Tamil Yearly Collections. Tamil Dubbed Movies Updates .... The movie is set in the fictional village of Solaiyur and revolves around a dam which is the lifeline for the village. The dam is under assessment for structural .... Lingaa is a 2014 Indian Tamil action-drama film directed by K.S. Ravikumar, who also ... The movie was filmed in Tamil, with Telugu and Hindi dubbed versions. ... Filmyzilla - Sarileru Neekevvaru Movie full movie in hindi Dubbed 480p. 1. lingaa telugu dubbed movie watch online 2. telugu lingaa full movie download Super Star Rajnikant Hindi dubbed Full Movie "LINGA" Sonakshi Sinha 02:28:21 ... Rajinikanth Telugu Super Hit Movie | Full Hd Movie | VIP Cinemas 02:18:24.. South Indian, Hit movies, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Hindi Dubbed, Superhit, Blockbuster, Action, Comedy, Thriller, Romance, Hindi, .... Lingaa telugu dubbed,watch Lingaa telugu movie online,Lingaa telugu full movie,download Lingaa telugu dubbed.. Movieswood ,New 2018 Telugu Movies, Download Tamil Hd Movies,Free Hindi Movies Download,Mobile Telugu Movies,HD Mp4 or High Quality Mp4.. A small-time thief reforms after learning about the role played by his grandfather in building a dam. lingaa telugu dubbed movie watch online lingaa telugu dubbed movie watch online, telugu lingaa full movie, telugu lingaa full movie download Soundcloud Bot Crack Sound Killer Cracked Pepperl ... Tamil for 'Lingaa' - Actress Sonakshi Sinha, who surprised Rajinikanth with ... She could have actually tried dubbing for herself in Tamil if not for the fact .. -

Rajini's Finger, Indexicality, and the Metapragmatics Of

Rajini’s Finger, Indexicality, and the Metapragmatics of Presence Constantine V. Nakassis, University of Chicago ABSTRACT This article explores the ways in which Tamil film stars, so-called mass heroes such as the “Superstar” Rajinikanth, are presenced in theatrical events of their onscreen revela- tion and apperception. Drawing on film analysis, ethnographic accounts of theatrical re- ception, and metadiscourse by filmgoers and industry personnel, I focus on Rajini’s onscreen pointing gestures in highly charged moments of presencing. As I argue, these data provoke reflection on indexicality—defined by Charles Sanders Peirce as a semiotic ground based on “real connection” or “existential relation,” such as copresence, contigu- ity, or causality—for at issue with Rajini’s fingers is precisely the question of his auratic being and presence. Instead of analyzing performative acts of presencing through appeal to the analytic of indexicality, then, what if we interrogate those ethnographic particular- ities of existence and presence that constitute the ground for indexical relations and ef- fects as such? Such an inquiry would refuse to leave indexicality as a self-evident, pregiven analytic, but instead pose it as an open ethnographic question. Opening up the question of existence and presence, as I show, allows us to unearth other semiotic “grounds” of indexicality and representation beyond those that we all too often take for granted. Contact Constantine V. Nakassis at Department of Anthropology, University of Chicago, 1126 E. 59th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 ([email protected]). An earlier version of this article was presented in the panel “Parsing the Body” at the AAA annual meet- ing, Washington, DC, December 4, 2014, organized by Mary Bucholtz and Kira Hall; an expanded draft was discussed at the workshop “Semiotics of the Image” (University of Chicago, October 14–15, 2016) with Chris- topher Ball, Lily Chumley, Keith Murphy, and Justin Richland. -

Indian English Women's Narratives from the 1950S to 1999

Review of Arts and Humanities June 2016, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 61-71 ISSN: 2334-2927 (Print), 2334-2935 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/rah.v5n1a6 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/rah.v5n1a6 Indian English Women’s Narratives from the 1950S to 1999: a Parallel Confrontation of Political Stories and Controversial her Stories Dr. Ana García-Arroyo1 Abstract In this article I attempt to establish a parallelism between some gender issues that emerge in modern post independence Indian society and their reflection in Indian English literature written by women writers. Guided by an accurate selection of works, in their great majority novels by Indian women writers in English, I aim to search out a parallel confrontation between the questions raised in the fictional narratives and the struggle of women at each particular her storical period: the Nehruvian time, the 70s-80s, the 90s and the globalized era. On the other hand I would also like to demonstrate that some of the fiction written by Indian female writers, and the issues discussed, transgress social and cultural patterns upheld by the hegemonic patriarchal power. As a result it will confirm how some of these Indian English narratives written by women writers have anticipated life. Keywords: Indian English narratives by women; Indian her story; gender issues; from1950-1999. It is well-known that the works by Plato and Aristotle have mostly influenced the world of theory and criticism. Their most influential contribution was to conceive literature as a didactic and mimetic expression, that is to say, an imitation or representation of life. -

Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota

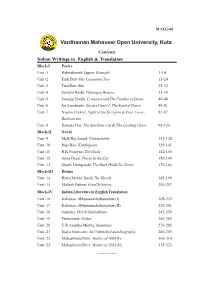

MAEG-08 Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Contents Indian Writings in English & Translation Block-I Poetry Unit -1 Rabindranath Tagore: Gitanjali 1-14 Unit -2 Toru Dutt: Our Casuarina Tree 15-24 Unit -3 Turu Dutt: Sita 25-32 Unit -4 Sarojini Naidu: Palanquin Bearers 33-39 Unit -5 Sarojini Naidu: Conquest and The Feather of Dawn 40-48 Unit -6 Sri Aurobindo: Savitri Canto I: The Symbol Dawn 49-81 Unit -7 Nissim Ezekiel: Night of the Scorpion & Poet, Lover, 82-97 Birdwatcher Unit -8 Kamala Das: The Sunshine Cat & The Looking Glass 98-120 Block-II Novel Unit -9 Mulk Raj Anand: Untouchable 121-128 Unit -10 Raja Rao: Kanthapura 129-141 Unit -11 R.K.Narayan: The Guide 142-155 Unit -12 Anita Desai: Voices in the City 156-169 Unit -13 Shashi Deshpande: The Dark Holds No Terror 170-184 Block-III Drama Unit -14 Rama Mehta: Inside The Haveli 185-199 Unit -15 Mahesh Dattani: Final Solutions 200-207 Block-IV Indian Literature in English Translation Unit -16 Kalidasa: Abhijnanashakuntalam (I) 208-225 Unit -17 Kalidasa: Abhijnanashakuntalam (II) 226-241 Unit -18 Sudraka: Mrichchhakatikam 242-259 Unit -19 Premchand: Godan 260-269 Unit -20 U.R.Anantha Murthy: Samskara 270-285 Unit -21 Indira Goswami: An Unfinished Autobiography 286-305 Unit -22 Mahashweta Devi: Mother of 1084 (I) 306-314 Unit -23 Mahashweta Devi: Mother of 1084 (II) 315-323 __________ Course Development Committee Chairman Prof. (Dr.) Naresh Dadhich Vice-Chancellor Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Convener and Members Prof. (Dr.) Rajul Bhargava Dr. Kshamata Chaudhary Formerly Prof. -

Rajinikanth and the “Regional Blockbuster”

Rajinikanth and the “Regional Blockbuster” * S. V. Srinivas Introduction In the recent past, Tamil and Telugu films have managed to find aud- iences beyond the southern region and have also competed with the biggest Hindi films in Hindi cinema’s traditional markets in northern and western India. A subset of these films are big-budget spectaculars, which I would like to call regional blockbusters. This term flags the critical import- ance of developments in the south Indian region and film industries for the emergence of relatively new production and narrative regimes which raise interesting questions of value—of films as commodities and stars alike.1 In the pages that follow, I trace the evolution of this form to argue that it is symptomatic of a fundamental transformation of industrial- political logics of south Indian cinemas, whose most visible manifest- ations so far have been the star politician and fan clubs. I propose that Rajinikanth is a useful point of entry into the discussion of the regional blockbuster because he belongs to a small number of Indian superstars who were a part of the very problem that the blockbuster attempts to overcome and, at the same time, a valuable asset for it. By tracking the career of Rajinikanth, I propose to show how crucial this star in par- ticular, but also the south Indian star vehicle known as the “mass film,” is the condition of possibility for a form that may or may not use major stars. The paper is divided into two parts. The first elaborates on the blockbuster as a descriptive-analytical category and shows why it is use- fully seen not just as a global form but also a regional phenomenon, pred- icated on locally specific historical contingencies as well industrial-aes- thetic practices.