Modern Woman and Identity in Rama Mehta's Inside The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Plan B.A. I 2016-17

Jaywant Pratishthan Humgaon Sanchalit Amdar Shashikant Shinde Mahvidyalay, Medha Department of English Teaching Plan B.A. I 2016-17 Sr. Month Paper Topic No. June Comp. Introduction to the syllabus and evaluation pattern Sentence Construction Paper I Introduction to the syllabus and evaluation pattern Introduction to literature July Comp. Sentence Construction Talking about persons, Objects and Places Describing Daily Routine Paper I Short Stories in English Characteristics of Short Story The Home Coming August Comp. The Runner A Frog Screams Grass Words Paper I The Cherry Tree Mr. Know-All September Comp. In Sahyadri Hills: a lesson in Humility The Bougainvillea Paper I The Refugee The Lumber Room October Comp. Narrating Experiences Revision Paper I Revision November Comp. Examinations Paper I December Comp. Application letter and C.V. The Final Decision Paper II Introduction to Novel as a Form of Literature Characteristics of Novel Lord of the Flies: Introduction , Chapters I, II January Comp. Writing News Reports My Education The Snake Trying Paper II Lord of the Flies- Chapters III, IV, V, VI, VII February Comp. Making Enquiries and Giving Instructions The Boy Comes Home Again Telephonic Conversation Paper II Lord of the Flies- Chapters VIII, IX, X, XI, XII March Comp. Revision Paper II Lord of the Flies Revision Subject Teacher Head Principal Jaywant Pratishthan Humgaon Sanchalit Amdar Shashikant Shinde Mahavidyalay, Medha Department of English Teaching Plan B.A. II 2016-17 Month Paper Topic June Comp Section I: Communication Skills Expressing Likes/Dislikes/Beliefs/Opinions Paper III Types of poems Paper IV Novel background July Comp Drafting Formal Notices Paper III G. -

Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210

ISSN-L 0537-1988 UGC Approved Journal (Journal Number 46467, Sl. No. 228) (Valid till May 2018. All papers published in it were accepted before that date) Cosmos Impact Factor 5.210 56 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Refereed Journal Vol. LVI 2019 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The responsibility for facts stated, opinions expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any in this journal, is entirely that of the author(s). The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA 56 2019 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri Professor of English, T.P.S. College, Patna (Bihar) DSW, Patlipurta University, Patna (Bihar) The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES) published since 1940 accepts scholarly papers presented by the AESI members at the annual conferences of Association for English Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the copies of journal for home, college, university/departmental library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Chhote Lal Khatri by sending an e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are requested to place orders on behalf of their institutions for one or more copies. Orders by post can be sent to the Editor- in-Chief, Indian Journal of English Studies, Anand Math, Near St. Paul School, Harnichak, Anisabad, Patna-800002 (Bihar) India. ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA Price: ``` 350 (for individuals) ``` 600 (for institutions) £ 10 (for overseas) Submission Guidelines Papers presented at AESI (Association for English Studies of India) annual conference are given due consideration, the journal also welcomes outstanding articles/research papers from faculty members, scholars and writers. -

Unit 17 General Introduction to the Indian English Novel

UNIT 17 GENERAL INTRODUCTION TO THE INDIAN ENGLISH NOVEL Structure 17.0 Objectives 17.1 Introduction 17.2 What is a Novel? 17.3 Aspects of the Novel. 17.3.1 Theme 17.3.2 Plot 17.3.3 Characterization 17.3.4 Point of View 17.3.5 Place and Time 17.3.6 Narration or Dramatization 17.3.7 Style 17.4 Types of Novels 17.4.1 Picaresque Novel$ 17.4.2 Gothic Novel 17.4.3 Epistolary Novel 17.4.4 Psychological Novel 17.4.5 Historical Novel 17.4.6 Regional Novel 17.4.7 Other typeslforms 17.5 The Rise of the Indian Novel in English 17.5.1 The Beginning 17.5.2 The Novel in the early 20* Century 17.5.3 Women's Writing 17.6 Shashi Deshpande 17.6.1 Shashi Deshpande as a Novelist 17.7 Glossary 17.8 Let Us Sum Up 17.9 Suggested Reading . 17.10 Answers to Exercises 17.0 OBJECTIVES The aim of this unit is to introduce you to the genre of the novel and trace its aspects. We also aim to familiarize you with the rise of the Indian novel in English. After studying this unit carefully and completing the exercises, you will be able to : outline the development of the novel and its types recognize its different aspects know the history of the Indian novel in English, and trace its development. 17.1 INTRODUCTION In this Block, we intend to introduce you to the genre of the novel, with special reference to Shashi Deshpande's The Binding Vine, prescribed in your course. -

Conclusion the Study of 'Construction and Contestation of Nation in Indian

Conclusion The study of 'Construction and Contestation of Nation in Indian English Fiction' was undertaken with the purpose of understanding the notion of nation underlying the texts and the alternative collectivity imagined therein. It has been carried out in this study by attending to three dimensions: the construction of collective identity, contestations of hegemonic construction of collective identity and visions of collective identities beyond the nation. Novels studied are all canonical texts and this selection was intended to enable a perspective into the 'mainstream' approaches to the issue of nations and nationalisms. The study does not present a detailed analysis of the novels in relation to the various content or form related aspects of the novel. For example, it does not enter into the exercise of exploring the psychological make up of characters, or the examination of the language used by the authors. Such and other investigations are employed in the study only in so far as they have a bearing on the issue under consideration. The idea behind restricting the scope is to keep the focus firmly on the issue being pursued. Three frameworks are adopted for the study. These frameworks are aimed at enabling a view of the notion of nation emerging at different historical junctures and in relation to various developments. However, the selection of novels for study under each framework is guided not by their year of publication or writing but by the period the stories relate to. As a result, while the novels discussed in each chapter have been published at various dates, they all concern themselves with roughly the same historical period. -

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K

The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Also by Prabhat K. Singh Literary Criticism Z Realism in the Romances of Shakespeare Z Dynamics of Poetry in Fiction Z The Creative Contours of Ruskin Bond (ed.) Z A Passage to Shiv K. Kumar Z The Indian English Novel Today (ed.) Poetry Z So Many Crosses Z The Vermilion Moon Z In the Olive Green Z Lamhe (Hindi) Translation into Hindi Z Raat Ke Ajnabi: Do Laghu Upanyasa (Two novellas of Ruskin Bond – A Handful of Nuts and The Sensualist) Z Mahabharat: Ek Naveen Rupantar (Shiv K. Kumar’s The Mahabharata) The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium Edited by Prabhat K. Singh The Indian English Novel of the New Millennium, Edited by Prabhat K. Singh This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Prabhat K. Singh All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4951-0, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4951-7 For the lovers of the Indian English novel CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 The Narrative Strands in the Indian English Novel: Needs, Desires and Directions Prabhat K. Singh Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 28 Performance and Promise in the Indian Novel in English Gour Kishore Das Chapter Three ........................................................................................... -

Indian English Women's Narratives from the 1950S to 1999

Review of Arts and Humanities June 2016, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 61-71 ISSN: 2334-2927 (Print), 2334-2935 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/rah.v5n1a6 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/rah.v5n1a6 Indian English Women’s Narratives from the 1950S to 1999: a Parallel Confrontation of Political Stories and Controversial her Stories Dr. Ana García-Arroyo1 Abstract In this article I attempt to establish a parallelism between some gender issues that emerge in modern post independence Indian society and their reflection in Indian English literature written by women writers. Guided by an accurate selection of works, in their great majority novels by Indian women writers in English, I aim to search out a parallel confrontation between the questions raised in the fictional narratives and the struggle of women at each particular her storical period: the Nehruvian time, the 70s-80s, the 90s and the globalized era. On the other hand I would also like to demonstrate that some of the fiction written by Indian female writers, and the issues discussed, transgress social and cultural patterns upheld by the hegemonic patriarchal power. As a result it will confirm how some of these Indian English narratives written by women writers have anticipated life. Keywords: Indian English narratives by women; Indian her story; gender issues; from1950-1999. It is well-known that the works by Plato and Aristotle have mostly influenced the world of theory and criticism. Their most influential contribution was to conceive literature as a didactic and mimetic expression, that is to say, an imitation or representation of life. -

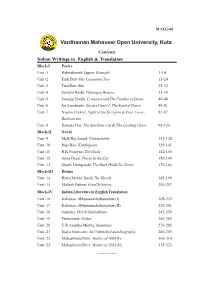

Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota

MAEG-08 Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Contents Indian Writings in English & Translation Block-I Poetry Unit -1 Rabindranath Tagore: Gitanjali 1-14 Unit -2 Toru Dutt: Our Casuarina Tree 15-24 Unit -3 Turu Dutt: Sita 25-32 Unit -4 Sarojini Naidu: Palanquin Bearers 33-39 Unit -5 Sarojini Naidu: Conquest and The Feather of Dawn 40-48 Unit -6 Sri Aurobindo: Savitri Canto I: The Symbol Dawn 49-81 Unit -7 Nissim Ezekiel: Night of the Scorpion & Poet, Lover, 82-97 Birdwatcher Unit -8 Kamala Das: The Sunshine Cat & The Looking Glass 98-120 Block-II Novel Unit -9 Mulk Raj Anand: Untouchable 121-128 Unit -10 Raja Rao: Kanthapura 129-141 Unit -11 R.K.Narayan: The Guide 142-155 Unit -12 Anita Desai: Voices in the City 156-169 Unit -13 Shashi Deshpande: The Dark Holds No Terror 170-184 Block-III Drama Unit -14 Rama Mehta: Inside The Haveli 185-199 Unit -15 Mahesh Dattani: Final Solutions 200-207 Block-IV Indian Literature in English Translation Unit -16 Kalidasa: Abhijnanashakuntalam (I) 208-225 Unit -17 Kalidasa: Abhijnanashakuntalam (II) 226-241 Unit -18 Sudraka: Mrichchhakatikam 242-259 Unit -19 Premchand: Godan 260-269 Unit -20 U.R.Anantha Murthy: Samskara 270-285 Unit -21 Indira Goswami: An Unfinished Autobiography 286-305 Unit -22 Mahashweta Devi: Mother of 1084 (I) 306-314 Unit -23 Mahashweta Devi: Mother of 1084 (II) 315-323 __________ Course Development Committee Chairman Prof. (Dr.) Naresh Dadhich Vice-Chancellor Vardhaman Mahaveer Open University, Kota Convener and Members Prof. (Dr.) Rajul Bhargava Dr. Kshamata Chaudhary Formerly Prof. -

Indian Women Writing: an Overview Vimal B Patel Research Scholar C.U.Shah University Surendranagar

ISSN 2454-8596 www.MyVedant.com An International Multidisciplinary Research E-Journal Indian Women Writing: An Overview Vimal B Patel Research Scholar C.U.Shah University Surendranagar Special Issue - International Online Conference V o l u m e – 5 , I s s u e – 5, May 2020 Page 1 ISSN 2454-8596 www.MyVedant.com An International Multidisciplinary Research E-Journal Abstract: This research paper aims to present how Indian women writers have put great effort in writing in English. Indian English Literature has got an independent status in the realm of world literature. Many different themes are dealt within Indian writing in English. Through the depiction of life, this literature continues to reflect Indian culture, tradition, social values and even Indian history in India. Recently, Indian English fiction has been trying to give expression to the Indian experience of the modern predicaments. Indian writing in English is now gaining ground rapidly. In the realm of fiction, it has heralded a new era and has earned many laurels both at home and abroad. Indian women writers have started questioning the prominent old patriarchal domination. They are no longer puppets in the hands of man. They played vital role in the field of literature. Keywords: Identity crisis, Alienation Introduction: Now a days, Indian Women writers have moved away from traditional portrayals of enduring self- sacrificing women, towards conflicts of female characters searching for identity. Most of Indian Women Writers write about inner life of women characters. The works of woman writers such as of Nayantara Sahgal, Kamla Markandaya, Anita Desai, Kamla Markandaya, Shashi Deshpande, Kiran Desai and Manju Kapur and many more. -

APPENDICES Contents Page No

APPENDICES Contents Page No. Table 2.1 “Theses of the Month” University News (2007-08) 286 Table 2.2 College-wise list of vocational courses for which affiliation is granted by North Maharashtra University, Jalgaon 286 Papers offered for BA (Special English) course study during 1993-94 to 2007-08 287 in the universities selected for present study Table 4.1 Papers offered in the University of Mumbai (UoM) for B.A. English (Major) during 1993-94 to 2006-07) 287 Table 4.2 Papers offered in the University of Pune (UoP) for B.A. (English Special) during 1993-94 to 2007-08 288 Table 4.3 Papers offered in Shivaji University, Kolhapur (SUK) for B.A. English (Special) during 1996-97 to 2006-07) 288 Documents of existing syllabi in the universities selected for present study 289 Papers offered for BA (Special English) course in other universities in 365 Maharashtra, states neighbouring Maharashtra and in other Indian states Table 4.4 B.A. (English) course in other Universities in Maharashtra 365 Table 4.5 B.A. (English) course in Universities from the states neighbouring Maharashtra 366 Table 4.6 (A) B.A. (English) courses in some Indian universities 367 Table 4 (A) The frequency of imperative words used in the objectives of papers offered in the universities selected 368 Table 4 (B) Question pattern of papers IV, VII and VIII offered in TYBA in the UoM 369 Table 4 (C) (i) Question pattern of papers G-II, S-I and S-II offered in SYBA (UoP) 370 Table 4 (C) (ii) Question pattern of papers G-II, S-I and S-II offered in SYBA (UoP) 370 Table 4 (D) Question pattern of papers V, VI and VII offered in TYBA in SUK 371 Table 4 (E) The questions words used in the ten question papers of Special English 372 Table 4 (F) The question words used in the question papers of Special English 373 Questionnaires 1. -

The Role of Indian Women Writers Empowring Their Rights”

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 1 March 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 “THE ROLE OF INDIAN WOMEN WRITERS EMPOWRING THEIR RIGHTS” Prof. Karabasappa.C.Nandihally Asst Professor in English Govt First Grade College – Davanagere Abstract This article analyzed Indian Women writing in English is being renowned as major contemporary current in English language- Literature. The like of Salman Rushdie, Amitav Gosh and Anita Desai have won worldwide acclaim for the excellence of their writing and their creative use of English. These consist of the role of English as global lingua franca: the position of English in India. The Indian writers in English are writing, not in their resident language but in a next language, and the consequential trans cultural character of their texts. 3.1. Conventional and Modern Indian English writing Traditionally, the work of Indian Women Writers has been undervalue due to patriarchal assumptions about the superior worth of male experience. The factors contributing to this intolerance is the fact that the majority of these women writers have observed no familial space. The Indian women's perception of their aspirations and prospect are within the construction of Indian social and moral commitment. Indian Women Writers in English are victims of a second prejudice vis-a-vis their regional counterpart’s. Proficiency in English is available only to writers of the intelligent, affluent and educated classes. Writer’s works are often therefore, belong to high social strata and cut off from the reality of Indian life. As, Chaman Nahal writes about feminism in India: “Both the knowledge of woman’s position in society as one of shortcoming or in majority compared with that of man and also a desire to remove those is advantages.” 1 3 2 the majority of novels written by Indian women writers depict the psychological sufferings of the frustrated homemakers. -

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach And

International Journal of Multidisciplinary Approach and Studies ISSN NO:: 2348 – 537X The Theory Of Karma In The Philosophical Novels Of Indian English Literature. Dr. Shrimati C. Das Post Doctoral Fellow(USA), Associate Professor, Department of English, Nehru Arts, Science, Commerce College & PG Center , Hubli, Karanataka. ABSTRACT: Most of Indian English literature quotes that the destination of each ones destiny is influenced by two important factors namely „Karma‟ and „Dharma‟. Karma is nothing but the action of life and the lessons we have to learn from it to correct our destiny, whereas Dharma means to live our life according to our duty to be done in this birth. Many of the Indian English novels project this basic principle of the theory of Karma that one‟s past Karma influences the present. This has been realized by the protagonists as they progress/digress in their lives. Many novels also reflect the „Law of Identical Harvest‟, which says that effects produced by our thoughts are more identical in nature to thought itself, like a corn reproduces only corn and a mango can reproduce only a mango. The events or happenings in the novels, to the protagonists, though not visible but are acted upon by a supreme force. The various protagonists realize the impact of such a force and are much wiser, and change course and try to move in the right direction- a trial and error exercise to finally meet their pre destined end. KEY WORDS: „Karma‟, „Dharma‟, „critical influence‟, „Law of Identical Harvest‟, „ historic approach‟, „Hindu concept‟, „fruition‟, „Karma Phala‟, „action-reaction‟, „predestined‟, „designated‟, „collective karma‟ 1 Indian English has become a new form of Indian culture and voice in which India speaks. -

Review of Literature

Review of Literature: In the post-colonial Indian Literature, themes regarding the gender issues have been the headquarters and center point of attraction of many Indian writers. The rise of feminist movement raised questions regarding the status of entire women community. Indian constitution, after independence, offered equal rights to Indian women. This changed the attitude of Indian women regarding their relationship with her family members. It also changed their attitude about the marriage. Women began to find themselves in the conflict of tradition and modernity and this made them alienated from self and society. Wave of feminism in India uplifted this problem and it produced many writers who evolved the concerns of Indian women in their work of art. Man- woman relationship, marital discord, gender discrimination, delineation of self, search for identity, male hegemony and female subordination, power and sexual politics etc. are the prevalent themes in the fiction of contemporary writers. To mention a few Kamala Markandaya‟s Nectar in a Sieve (1954), A Silence of Desire (1960), Two Virgins(1973), Shashi Deshpande‟s That Long Silence (1988), Binding Wine(1993), A Matter of Time (1996), Moving On (2004), Roots and Shadows, Dark Hold No Terror, Anita Desai‟s Cry, the Peacock, Fire on the Mountain, Fasting, Feasting (1999), Voices in the City, Nayantara Sahgal‟s The Day in Shadow (1971), Jai Nimbkar‟s Temporary Answers(1974), A Joint Venture(1988), Githa Hariharan‟s The Thousand Faces of Night (1992), Shobha De‟s Socialite Evenings (1989), Rama Mehta‟s Inside the Haveli (1977), Bharti Mukherjee‟s Jasmine (1989), Desirable Daughters (2003), Arundhati Roy‟s God of Small of Thing (1997), Namita Gokhale‟s Paro: Dreams of Passions(1984), Manju Kapur‟s Difficult Daughters (1998), Uma Vasudev‟s The Song of Anusaya (1978), Anjana Appachana‟s Listening Now (1998), Chitra Banerji Divakaruni‟s Sister of My Heart (1999), The Vine of Desire (2002) and many more.