Rajini's Finger, Indexicality, and the Metapragmatics Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

Short+Sweet Theatre Festival South India (2016) About Short+Sweet 2016

Short+Sweet Theatre Festival South India (2016) About Short+Sweet 2016 Short+Sweet (originally known as Short & Sweet) is a multi-form arts platform presenting festivals in theatre, dance, music-theatre, comedy and cabaret across Australia and Asia. Short+Sweet's vision statement is: a more creative world ten minutes at a time. The flagship festival is Short+Sweet Theatre Sydney, the largest ten-minute play festival in the world. Short+Sweet Theatre was founded at the Newtown Theatre in Sydney, Australia in January 2002 by Mark Cleary, beginning with the first ever Short+Sweet Theatre festival. Festivals are now held across the globe. Short+Sweet Theatre Sydney is now the largest ten-minute theatre festival in the world, with around 180 new plays being produced every season. There are many unique elements to this festival, some of which are, a strict time-limit, limit of one play per playwright, one play per director and two plays per actor, people's choice voting and the competitive aspect of the festival where plays are chosen from each week to progress to the Gala Finals. Short+Sweet South India started as Short+Sweet Chennai in 2011. Since 2014, the festival has opened to entries from the four southern states in India. The jury members for the weeks are not known to the public, and consist of a good mix of connoisseurs from diverse fields. The festival is presented in association with Blu Lotus Foundation and Alliance Francaise of Madras. Currently, Meera Krishnan, senior programme coordinator at Prakriti Foundation, is the Festival Director. -

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2012-2013 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT (%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 67059 0.002525667 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 579134 0.021812132 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1172263 0.044151362 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 373181 0.01405525 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 390958 0.014724791 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 172950 0.006513878 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 366211 0.013792736 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 398436 0.015006438 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 180263 0.00678931 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 265972 0.010017399 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 4172 0.000157132 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 297035 0.011187336 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410280 HELAPURI NEWS TELUGU DAILY(E) 67795 0.002553387 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 152550 0.005745545 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410405 VASISTA TIMES TELUGU DAILY(E) 62805 0.002365447 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 369397 0.013912732 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 239960 0.0090377 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 209853 -

Top 200+ Current Affairs Monthly MCQ's September

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 1 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q1.India's first-ever sky cycling park to be opened in which city? (a) Manali (b) Mussoorie (c) Nainital (d) Shimla (e) None of these Ans.1.(a) Exp.To boost tourism and give and an all new experience to visitors, India's first-ever sky cycling park will soon open at Gulaba area near Manali in Himachal Pradesh. It is 350m long & is located at a height of 9000 Feet above sea level. Forest Department and Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Mountaineering and Allied Sports have jointly developed an eco-friendly park. AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | ONLINE TEST SERIES: TEST.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM | MAIL 2 US AT [email protected] Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q2.Which sportsperson has won the 2019 Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar? (a) Abhinav Bindra (b) Jeev Milkha Singh (c) Mary Kom (d) Gagan Narang (e) None of these Ans.2.(d) Exp.On 2019 National Sports Day (NSD), Gagan Narang and Pawan Singh have been honoured with the Rashtriya Khel Protsahan Puraskar for their Gagan Narang Sports Promotion Foundation (GNSPF) at the Arjuna Awards ceremony in Rashtrapati Bhavan, New Delhi. The award recognizes their contribution in the growth of their favourite sport and a reward for sacrifices they have made to realize their dream. In 2011, Narang and co-founder Pawan Singh founded GNSPF to nurture budding talent -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 54.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 41] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 Aippasi 6, Vijaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 2893-3026 Notice .. 3026-3028 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 43888. My son, D. Ramkumar, born on 21st October 1997 43891. My son, S. Antony Thommai Anslam, born on (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 4/81C, Lakshmi 20th March 1999 (native district: Thoothukkudi), residing at Mill, West Colony, Kovilpatti, Thoothukkudi-628 502, shall Old No. 91/2, New No. 122, S.S. Manickapuram, Thoothukkudi henceforth be known as D. RAAMKUMAR. Town and Taluk, Thoothukkudi-628 001, shall henceforth be G. DHAMODARACHAMY. known as S. ANSLAM. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) M. v¯ð¡. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) 43889. I, S. Salma Banu, wife of Thiru S. Shahul Hameed, born on 13th September 1975 (native district: Mumbai), 43892. My son, G. Sanjay Somasundaram, born residing at No. 184/16, North Car Street, on 4th July 1997 (native district: Theni), residing Vickiramasingapuram, Tirunelveli-627 425, shall henceforth at No. 1/190-1, Vasu Nagar 1st Street, Bank be known as S SALMA. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Results Cafoundation Cacpt

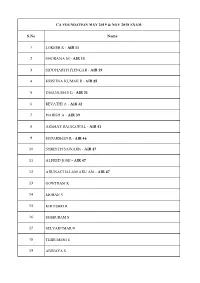

CA FOUNDATION MAY 2019 & NOV 2018 EXAM S.No Name 1 LOKESH K - AIR 11 2 SHOBANA M - AIR 15 3 SIDDHARTH IYENGAR - AIR 19 4 KRISHNA KUMAR R - AIR 25 5 DHANUSH S G - AIR 31 6 REVATHI A - AIR 32 7 HARISH A - AIR 39 8 AKSHAY RAJAGOPAL - AIR 41 9 SUDARSHAN R - AIR 46 10 SHRESTH SAWARN - AIR 47 11 ALFRED JOSE - AIR 47 12 ARUNACHALAM ARU AM - AIR 47 13 GOWTHAM K 14 MOHAN V 15 KIRTISHRI R 16 SUBBURAM S 17 SELVAKUMAR N 18 THIRUMENI E 19 ABINAYA S 20 YOKESH R 21 SANTHOSSH S 22 LOGESH S 23 SETHURAMAN S 24 SAJEETHAMBIGAI 25 JAYSUHITH TK 26 ARAVIND S 27 DHARAN KUMAR S 28 SANTHOSH P 29 SUGANTHI N 30 AHAMED BASHA T 31 MOHAMED NIYAS J 32 MOHAMMED SOHAILATHAR 33 AJAY KUMAR M 34 ASHWIN P 35 AJAY M 36 BALAJI M 37 CHANDRASEKAR V 38 AMRUDHA VARSHINI T S 39 GANESH V 40 VIVEGA V 41 PRAGATHI R 42 SURENDHER KUMAR S 43 SARAVANAN V 44 GOWTHAM G 45 SRIVATSAN A 46 NANDHINI DEVI 47 KARTHIKEYAN M 48 YAMINI V S 49 AJITH KUMAR M 50 SARAN PRASATH 51 ABINESH R 52 DESIKA A 53 MONIKA M 54 AADHITHIYA P 55 ABDULLAH TAHA 56 SANDESH A 57 BOOLIBHARATH R 58 SELVAMANI S 59 SUVEDHA R 60 HAJIRA SULTHANA D 61 PADMAVATHY S 62 SINGARAVELAN N 63 MANIKANDAN V 64 CAROLIN ROSE C 65 AAKASH A 66 SANKARA NARAYANAN V 67 DHEVIYA S 68 RAHITH R 69 DINESH V 70 GAYATHRE J 71 SIVA KUMAR S 72 SHALINI SIVAKUMAR 73 KARTHICK B 74 ISHWARYA G 75 SRIKANTH V 76 MAHALAKSHMI C 77 AMRITHA PRIYADHARSHINI 78 ABIRAMI V 79 SHARMILA C K 80 SUJITHA R 81 VINAY D 82 GURUPRASATH 83 VIJAY MANI K 84 BASKARAN S 85 OVIYA N 86 LEON NOEL M 87 AFFAN JAWEED GUNDU 88 PRASANNA RAMANAA MV 89 DINESH M 90 MOHAMED ANSAR 91 SREEKANTH -

Tirupathi Priyasakhi Kanaa Kanden Sachein Chellame Thirutta Payale

Thirutta Payale Kanaa Kanden STARRING : Jeevan, Abbas,Sonia Agarwal, Vivek STARRING : Srikanth, Gopika,Prithviraj DIRECTOR : Susi Ganeshan MUSIC : Vidyasagar YEAR OF PRODUCTION : 2003 DIRECTOR : K.V Anand YEAR OF PRODUCTION : 2005 SYNOPSIS : The story revolves around Manickam, a good for nothing youth, who throws his weight around his house with his violent attitude. One day in a fit of rage, he injures his younger brother, following which he is sent SYNOPSIS :The movie begins with Bhaskar (Srikanth) visiting his village for his friend off to Madras to his maternal uncle's house. Archana's (Gopika) wedding. But he ends up in returning to city with Gopika herself for His uncle an upright policeman loves Manickam very much and welcomes him home hoping to change him with she comes to know of the bridegroom's bad past in the village just before the marriage. his soft approach. At his uncle's place, Manickam whiles away his time on the terrace with a pair of binoculars in Friends since their childhood days, the couple begins to live in a small house owned by hand. A young couple, Roopini and Santosh playing golf everyday catch his fancy while surveying the Vivek in Chennai. Meanwhile, Bhaskar, a research scholar in Chemistry, succeeds in neighbourhood through the binoculars. The duo is in a clandestine relationship carried on behind their spouses coming out with a prototype of a desalination plant which he wants to give to the back and this is closely followed by Manickam everyday. government and solve the water crisis in Chennai. One evening, he video records their intimate relationship and with that he begins to blackmail Roopini, who is married to a young He eventually gets discouraged by the government authorities and even the State Minister. -

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applica Ons For

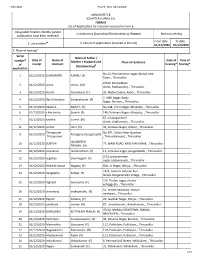

11/21/2020 Form9_AC2_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Ponneri Revision identy applicaons have been received) From date To date 1. List number@ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial Name of Father / number$ Date of Name of Date of Time of Mother / Husband and Place of residence of receipt claimant hearing* hearing* (Relaonship)# applicaon No. -

Probe on Royal Deaths

VOL.I WEDNESDAY K 24 K Y Y M ISSUE NO.253 M C AUGUST, 2016 C BHUBANESWAR THE KALINGA CHRONICLE PAGES-8 2.50 (Air Surcharge - 0.50P) FIND US ON FOLLOW US facebook.com/thekalingachronicle Popular People’s Daily of Odisha ON TWITTER twitter.com/ thekalingachronicle Probe on Royal Deaths China eyes Odisha Bhubaneswar (KC- It is expected Chinese repre- Bhubaneswar (KC- The Police on "house arrest" and August found out priating royal prop- N): As China experi- that collaborations sentatives said they N): A day after the 21 August recovered "misappropriation of Sanjay Patra's body erty". ence over produc- between India and are encouraged by mysterious deaths of bodies of the former royal family proper- hanging from the In a letter to the tion in all sectors, China will carry for- the new IPR Policy former manager of palace Manager ties". ceiling while bodies Chief Minister, Parlakhemundi pal- Anang Manjari Patra, Meanwhile, of Anang Manjari and Mr.Deb's daughter ace Anang Manjari her brother and Ma- three suicide notes her sister Bijaylaxmi Kalyani Devi, who is Patra and her two sib- haraja Gopinath have been recovered were found in an- currently staying in from Anang Manjari other room of the Chennai, had urged Patra's house, DGP House. him to inquire into K B Singh told Me- Santosh alias the property transac- dia Men here.He said Tulu was rescued in tions of the royal the suicide notes critical condition family for the past were written in sepa- from the kitchen, 35 years. rate handwritings. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

A Study on Visual Story Telling Techniques of Maniratnam Movies: Cinematography and Mise En Scene Analysis of Selected Movies

Annals of R.S.C.B., ISSN:1583-6258, Vol. 25, Issue 6, 2021, Pages. 9599 - 9606 Received 25 April 2021; Accepted 08 May 2021. A Study on Visual Story Telling Techniques of Maniratnam Movies: Cinematography and Mise en scene Analysis of Selected Movies 1 2 Mena M, Varun Prabha T 1Post Graduate Student, MA JMC,Dept.of Visual Media and Communication,Amrita School of Arts and Sciences,Amrita VishwaVidyapeetham, Kochi, India 2Assistant Professor, Dept.of Visual Media and Communication,Amrita School of Arts and Sciences,Amrita VishwaVidyapeetham, Kochi, India Abstract Visually representing a story is an art. Mastering that art and capturing human minds into the soul of the characters of the film and mirroring the very own society was part of Mani Ratnam’s life for the past three decades. This research paper points towards some of the techniques employed and experiments conducted in visual storytellingin his various projects by using Miseen scene elements and cinematography in beautiful ways. In Roja what he Sasnthosh Sivan and Mani Ratnam experimented was painting the reflectors green, to look the grass greener than it actually is. In Thapalathy, Mani ratnam projected a yellowish light, like an aura into the protagonist which symbolizes his history and background. In Bombay, he throughout kept a blue tone in order to gives an element of mystery in the film. In Raavanan, he played with shades and light and that too in two different ways at the beginning and at the end of the films. In Alaipayuthe he presented the story more through the movements of camera and through micro expressions and symbolizations.Theglobalization and evolution of Indian Cinematography can be traced out through the works of Mani Ratnam.