Rajinikanth and the “Regional Blockbuster”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Hindi Song Book

1 Hindi Text Listing 33 Movie/singer order NO. TITLE MOVIE/SINGER COMPOSED BY 206 EK LADKI KO DEKHA TO AISA LAGA 1942 A LOVE STORY KUMAR SANU 521 PYAR HUA CHUPKE SE 1942 A LOVE STORY KAVITA KRISHNAMURTHY 539 RIMJHIM RIMJHIM 1942 A LOVE STORY KUMAR SANU , KAVITA K. 544 ROOTH NA JANA 1942 A LOVE STORY KUMAR SANU 677 YE SAFAR BAHUT HAI KATHIN MAGAR 1942 A LOVE STORY SHIVAJI CHATOPADHYAYA 421 MERA DIL TERA DIWAANA AA AB LAUT CHALEN ALKA UDIT 6038 KILIYE KILIYE AA RATHRI S. JANAKI 399 MAI GAREEBON KA DIL HOON AABE HYAAT HEMANT KUMAR 9 AAJ MERE YAAR KI SHAADI HAI AADMI SADAK KA MOHD.RAFI 11 AAJ PURANI RAAHON SE AADMI MOHD. RAFI 452 NA AADMI KA KOI BHAROSA AADMI MO. RAFI 13 AAJA RE AAH LATA MANGESHKAR & MUKESH 284 JAANE NA NAZAR AAH LATA MANGESHKAR, MUKESH 533 RAJA KI AAYEGI BARAT AAH LATA MANGESHKAR 222 GORIYA RE GORIYA RE AAINA LATA, JOLLY MUKHARJEE 43 ACHHA TO HUM CHALTE HAI AAN MILO SAJANA LATA, KISHORE KUMAR 19 AAN MILO SAJNA AAN MILO SAJNA LATA MANGESHKAR, MOHD.RAFI 661 YAHAAN WAHAAN SAARE AAN MILO SAJNA KISHORE KUMAR 8 AAJ MERE MANN MEIN SAKHI AAN LATA MANGESHKAR 105 BUS MERI JAAN BUS AANCHAL LATA, KISHORE KUMAR 275 IS MOD SE JAATE HAI AANDHI LATA MANGESHKAR 215 GAYA BACHPAN AANKHON ANKHON MEIN LATA MANGESHKAR 434 MERI AANKHON MEIN TUM HO AANKHON MEIN TUM HO ALKA, UDIT NARAYAN 227 GUNI JANO BHAKT JANO AANSOON AUR MUSKAAN KISHORE KUMAR 22 AAP AAYE BAHAAR AAYI AAP AAYE BAHAAR AAYI MOHD. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 54.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 41] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 23, 2013 Aippasi 6, Vijaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 2893-3026 Notice .. 3026-3028 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 43888. My son, D. Ramkumar, born on 21st October 1997 43891. My son, S. Antony Thommai Anslam, born on (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 4/81C, Lakshmi 20th March 1999 (native district: Thoothukkudi), residing at Mill, West Colony, Kovilpatti, Thoothukkudi-628 502, shall Old No. 91/2, New No. 122, S.S. Manickapuram, Thoothukkudi henceforth be known as D. RAAMKUMAR. Town and Taluk, Thoothukkudi-628 001, shall henceforth be G. DHAMODARACHAMY. known as S. ANSLAM. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) M. v¯ð¡. Thoothukkudi, 7th October 2013. (Father.) 43889. I, S. Salma Banu, wife of Thiru S. Shahul Hameed, born on 13th September 1975 (native district: Mumbai), 43892. My son, G. Sanjay Somasundaram, born residing at No. 184/16, North Car Street, on 4th July 1997 (native district: Theni), residing Vickiramasingapuram, Tirunelveli-627 425, shall henceforth at No. 1/190-1, Vasu Nagar 1st Street, Bank be known as S SALMA. -

2 States the STORY of MY MARRIAGE

DX @ www.desibbrg.com DX @ www.desibbrg.com This eBook is exclusively made by bombayboy4u_2005 & perfectblue for www.desibbrg.com ~Greetings to~ BG MTB & all DBBRG members Da Xclusives @ WWW.DESIBBRG.COM DX @ www.desibbrg.com 2 States THE STORY OF MY MARRIAGE DX @ www.desibbrg.com Love marriages around the world are simple: Boy loves girl. Girl loves boy. They get married. In India, there are a few more steps: Boy loves Girl. Girl loves Boy. Girl's family has to love boy. Boy's family has to love girl. Girl's Family has to love Boy's Family. Boy's family has to love girl's family. Girl and Boy still love each other. They get married. Welcome to 2 States, a story about Krish and Ananya. They are from two different states of India, deeply in love and want to get married. Of course, their parents don’t agree. To convert their love story into a love marriage, the couple have a tough battle in front of them. For it is easy to fight and rebel, but it is much harder to convince. Will they make it? From the author of blockbusters Five Point Someone, One Night @ the Call Center and The 3 Mistakes of My Life, comes another witty tale about inter-community marriages in modern India. DX @ www.desibbrg.com This may be the first time in the history of books, but here goes: Dedicated to my in-laws* *which does not mean I am henpecked, under her thumb or not man enough DX @ www.desibbrg.com PROLOGUE “Why am I referred here? I don’t have a problem,” I said. -

![208] Chennai, Saturday, May 23, 2020 Vaikasi 10, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1879/208-chennai-saturday-may-23-2020-vaikasi-10-saarvari-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2051-721879.webp)

208] Chennai, Saturday, May 23, 2020 Vaikasi 10, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2020 [Price: Rs. 11.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 208] CHENNAI, Saturday, may 23, 2020 Vaikasi 10, Saarvari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2051 Part II—Section 2 Notifications or Orders of interest to a Section of the public issued by Secretariat Departments. NOTIFicationS BY GOVERNMENT REVENUE AND DISASTER MANAGEMENT Department COVID-19 – INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL – EXTENDING RESTRICTIONS IN THE territorial JURISDICTIONS OF THE State OF TAMIL NADU. [G.O. (Ms.) No. 247, Revenue and Disaster Management (DM-II), 23rd May 2020, ¬õè£C 10, ꣘õK, F¼õœÀõ˜ ݇´-2051.] No. II(2)/REVDM/348(L-1)/2020. WHEREAS in the reference third and fourth read above, the Government have extended the State-wide lockdown from 00:00 hrs of 17-5-2020 till 24:00 hrs of 31-5-2020 under the Disaster Management Act, 2005 with various relaxations ordered in G.O.Ms.No.217, Revenue and Disaster Management (DM-II) Department, dated 3-5-2020 and amendments issued thereon with State specific existing restrictions and new relaxations. WHEREAS the Public and auto rickshaws Drivers associations have requested the Government to permit auto rickshaws for movement of persons. NOW THEREFORE the Government issue the following amendment to G.O.Ms.No.245, Revenue & Disaster Management (DM-II) Department, dated 18-5-2020: A) the sub-clause "Taxi and auto rickshaws are permitted for urgent medical treatment with TN e-pass within the District, in respect of 12 Districts where Intra District movements are otherwise not permitted" under Clause V shall be replaced as "Taxi are permitted for urgent medical treatment with TN e-pass within the District, in respect of 12 Districts where Intra District movements are otherwise not permitted. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

230239875.Pdf

======================================================================== ======================================================================== Log Report - Stellar Phoenix NTFS Data Recovery v4.1 ======================================================================== ======================================================================== ------------------------------------------------------------------------ Recovering File ---------------------------------------------------------------- -------- - Process started - Started on: Apr 20 2014 , 11:33 AM - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Amanda.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160 gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Despertar.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160 gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Din Din Wo (Little Child).wma - [Recov ered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Distance.wma - [Recov ered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\I Guess You're Right.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\I Ka Barra (Your Wor k).wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Love Comes.w ma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Muita Bobeir a.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\OAM's Blues. wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\One Step Bey ond.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\Symphony_No_ 3.wma - [Recovered] - E:\160gb data\Lost folder(s)\Folder 10593\desktop.ini - [Recovered] - Process completed - Completed on : Apr 20 2014 , 11:41 AM ------------------------------------------------------------------------ -

List of Polling Stations for 111 Mettupalayam Assembly Segment

List of Polling Stations for 111 Mettupalayam Assembly Segment within the 19 The Nilgiris Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling station Location and name of building in Polling Areas Whether for All No. which Polling Station located Voters or Men only or Women only 12 3 4 5 1 1 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Nellithurai (R.V) and (P) Nellithurai Ward No. 1 , 2.Nellithurai (R.V) and (P) All Voters School, East Portion North Facing Nandhavanam Pudur B W.No. 1 VI th Std Class Room Nellithurai - 641305 2 2 Sarguru adivasi Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Narayanasamy Pudur W.No. 1 , 2.Odanthurai (R.V) and All Voters School, East Facing southern side (P) Naripallamroad Mampatti W.No.1 , 3.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Ootyroad Gandhi Nagar - 641305 Puliyamarathuroad W.No.1 , 4.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Ootyroad Sunnambukalvai W.No.1 , 5.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Jallimedu Ooty Road W.No.1 , 6.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Railway Station W.No. 2 , 7.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Ooty Road Kallar W.No.2 3 3 Sarguru adivasi Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Pudur W.No. 2 , 2.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) All Voters School, East Facing North side Sachidhanantha Jothi Negethan Valagam W.No. 2 , 3.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Gandhi Nagar - 641305 Kallar Pudur, Railwaygate, Thuripalam W.No.2 , 4.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Naripallam Road Vinobaji Nagar W.No.2 , 5.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Tribal Colony W.No.2 , 6.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Samathuvapuram W.No.2 , 7.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar T.A.S.A Nagar W.No.2 , 8.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Agasthiyar Nagar W.No.2 4 4 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Omaipalayam Killtheru W.No 3,4 , 2.Odanthurai (R.V) All Voters School, West FacingSouth side and (P) Omaipalayam Meltheru W.No 3,4 RCC building Oomapalayam 641305 5 5 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Omaipalayam Pudhu Harizana Colony W.No. -

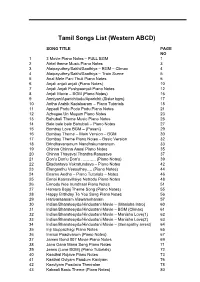

Tamil Songs List (Western ABCD)

Tamil Songs List (Western ABCD) SONG TITLE PAGE NO 1 3 Movie Piano Notes – FULL BGM 1 2 Airtel theme Music Piano Notes 3 3 Alaipayuthey/Sakhi/Saathiya – BGM – Climax 4 4 Alaipayuthey/Sakhi/Saathiya – Train Scene 5 5 Anal Mele Pani Thuli Piano Notes 6 6 Anjali anjali anjali (Piano Notes) 10 7 Anjali Anjali Pushpaanjali Piano Notes 12 8 Anjali Movie – BGM (Piano Notes) 16 9 Anniyan/Aparichitudu/Aparichit (Sister bgm) 17 10 Antha Arabik Kadaloaram – Piano Tutorials 18 11 Appadi Podu Podu Podu Piano Notes 21 12 Azhagae Un Mugam Piano Notes 23 13 Bahubali Theme Music Piano Notes 25 14 Bale bale bale Bahubali – Piano Notes 27 15 Bombay Love BGM – (Pasani) 29 16 Bombay Theme – Main Version – BGM 30 17 Bombay Theme Piano Notes – Basic Version 32 18 Brindhavanamum Nandhakumaranum 33 19 Chinna Chinna Aasai Piano Notes 35 20 Chinna Thayaval Thantha Raasaave 37 21 Don’u Don’u Don’u ……….. (Piano Notes) 39 22 Ekadantaya Vakratundaya – Piano Notes 42 23 Elangaathu Veesuthey…. (Piano Notes) 44 24 Enamo Aedho – Piano Tutorials – Notes 46 25 Ennai Kaanavillaiye Netrodu Piano Notes 48 26 Ennodu Nee Irundhaal Piano Notes 51 27 Hamara Bajaj Theme Song (Piano Notes) 55 28 Happy Birthday To You Song Piano Notes 56 29 Harivarasanam Viswamohanam 57 30 Indian/Bharateeydu/Hindustani Movie – (Manisha Intro) 60 31 Indian/Bharateeydu/Hindustani Movie – BGM (Climax) 61 32 Indian/Bharateeydu/Hindustani Movie – Manisha Love(1) 62 33 Indian/Bharateeydu/Hindustani Movie – Manisha Love(2) 63 34 Indian/Bharateeydu/Hindustani Movie – (Senapathy arrest) 64 35 Inji Iduppazhagi -

SRNO Name Gender Catergory Scale Specialzationbranch / Office Date of Birth Retirement 3761 KAMAL NAIN MALE GEN SCALE2 CDPC

SRNO Name Gender Catergory Scale SpecialzationBranch / Office Date Of Birth Retirement 3761 KAMAL NAIN MALE GEN SCALE2 CDPC, DELHI 03/03/1953 Mar 2013 5124 BAL RAM GUPTA MALE GEN SCALE6 ZO:KOLKATA 05/04/1953 Apr 2013 5224 VENKATARAMAN C S MALE GEN SCALE6 ZO:TIRUNELVELI 10/04/1953 Apr 2013 5251 NIKHIL KUMAR SARKAR MALE SC SCALE5 ZO:AHMEDABAD 23/11/1953 Nov 2013 5279 DEEPAK ANANTRAO HEREKAR MALE GEN SCALE4 ZO:SALEM 29/07/1953 Jul 2013 5309 DEVENDRA PAL SINGH MALE GEN SCALE7 CORPORATE OFFICE 20/04/1953 Apr 2013 5318 BIDYASIS BANDYOPADHYAY MALE GEN SCALE4 ZO:PATNA 01/10/1953 Sep 2013 5329 SREEKUMAR C MALE GEN SCALE4 ZO:PUNE 22/05/1953 May 2013 5333 AMRESH KUMAR MALE GEN SCALE7 CORPORATE OFFICE 20/07/1953 Jul 2013 5343 ULAGAN D A MALE SC SCALE7 ZO:PUDUCHERRY 11/01/1953 Jan 2013 5344 SHEKHAR GHOSE MALE GEN SCALE3 ZO:KOLKATA 11/02/1954 Feb 2014 5350 NADKARNI RAGHUNANDAN NAGESH MALE GEN SCALE4 CO: INSPECTION DEPT 02/07/1954 Jul 2014 5355 NARENDRA SINGH KHAMESRA MALE GEN SCALE6 ZO:KOLKATA 25/02/1953 Feb 2013 5368 DAKHINESWAR HEMBRAM MALE ST SCALE2 BHUBANESHWAR C C 04/03/1954 Mar 2014 5389 BANABIHARI PANDA MALE GEN SCALE7 I B M B S CHENNAI 06/11/1955 Nov 2015 5390 SHYAMLAL KUMAR SINHA MALE GEN SCALE4 INSP. CENTRE, NEW DELHI 10/01/1953 Jan 2013 5397 SHAH HARSHAD VINOD CHANDRA MALE GEN SCALE3 ZO:AHMEDABAD 09/10/1955 Oct 2015 5403 PUSHPARAJ S MALE SC SCALE7 CORPORATE OFFICE 13/03/1953 Mar 2013 5404 RAJAGOPAL SUNDARAM MALE GEN SCALE3 MALAD 17/01/1954 Jan 2014 5407 KAMAL NATH JHA MALE GEN SCALE4 ZO:PATNA 02/12/1952 Dec 2012 5408 MALATHY K FEMALE GEN SCALE7 CORPORATE OFFICE 15/05/1955 May 2015 5415 SURESH TIRATHDAS IDNANI MALE GEN SCALE4 KAROL BAGH 10/07/1955 Jul 2015 5416 GOPAL CHANDRAYAN MALE GEN SCALE5 INSP. -

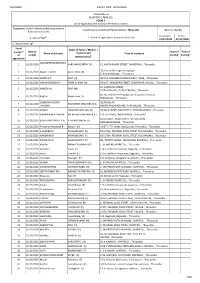

12/2/2020 Form9 AC4 02/12/2020 1/20 ANNEXURE

12/2/2020 Form9_AC4_02/12/2020 ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V, PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applicaons for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated locaon identy (where applicaons Constuency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Thiruvallur Revision identy have been received) From date To date @ 2. Period of applicaons (covered in this list) 1. List number 01/12/2020 01/12/2020 3. Place of hearing* Serial Name of Father / Mother / $ Date of Date of Time of number Name of claimant Husband and Place of residence of receipt hearing* hearing* (Relaonship)# applicaon NAVANEETHAKRISHNAN 1 01/12/2020 KARUNAMOORTHY (F) 15, KANTHASAMY STREET, THANDURAI, , Thiruvallur 38, Saraswathi nagar,murugappa 2 01/12/2020 MARKET MERY ARUL DOSS (H) 5, thirumullaivoyal, , Thiruvallur 3 01/12/2020 SUJATHA R RAVI (H) NO 150, JAGAJEEVAN RAM STREET, TIRUR, , Thiruvallur 4 01/12/2020 NADHIYA BEGUM P PREM KUMAR (H) NO 107, AMBEDKAR STREET, VENGATHUR VILLAGE, , Thiruvallur 10, SANNATHI STREET, 5 01/12/2020 NARESH M DEVI (M) THIRUVERKADU, THIRUVERKADU, , Thiruvallur No 28, 2nd Street Periyakasi Koil Kuppam , Ernavoor 6 01/12/2020 Kughan Kuppusamy (F) Kavakkam, , Thiruvallur SABEENA HALEMA 30,SRI BALAJI 7 01/12/2020 MOHAMED SIRAJ SIRAJ (H) HALEMA NAGAR, PALLAKAZHANI, THIRUVALLUR, , Thiruvallur 8 01/12/2020 JANAKI LAKSHMI KANTHAN (F) 50/30, BHARATHIYAR STREET , PERIYAKKUPPAM, , Thiruvallur 9 01/12/2020 NARAYANAN P PALANI PALANI KOTHANDAPANI (F) 133, P H ROAD, ONDIKUPPAM, , Thiruvallur NO 43/580 F, ANNA STREET, RAJAJIPURAM , 10 01/12/2020 ESWARAMOORTHY P H P HARIKRISHNAN (F) KAMARAJAPURAM, , -

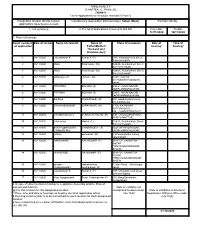

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications For

ANNEXURE 5.8 (CHAPTER V , PARA 25) FORM 9 List of Applications for inclusion received in Form 6 Designated location identity (where Constituency (Assembly/£Parliamentary): Salem (West) Revision identity applications have been received) 1. List number@ 2. Period of applications (covered in this list) From date To date 16/11/2020 16/11/2020 3. Place of hearing * Serial number$ Date of receipt Name of claimant Name of Place of residence Date of Time of of application Father/Mother/ hearing* hearing* Husband and (Relationship)# 1 16/11/2020 Lokeshwaran K Kumar A (F) 1/39, Vinayagar kovil street, Sarkarkollapatty, , 2 16/11/2020 Malar Palanisamy (W) 3/242A, Arunthathiyar Street, Saminaickenpatti, , 3 16/11/2020 Malar Palanisamy (W) 3/242A, Arunthathiyar Street, Saminaickenpatti, , 4 16/11/2020 sathyasree sri kumari i (M) 3/168 , kannagi street,jagirammapalayam , salem, , 5 16/11/2020 PRIYANKA SELVAM (F) 5/33-C, AVVAI NAGAR, JAGIR AMMAPALAYAM, , 6 16/11/2020 PRITHIKA SELVAM (F) 5/33/C, AVVAI NAGAR, JAGIR AMMAPALAYAM, , 7 16/11/2020 Santhiya Chinnathambi (H) 210, Aadidravidar Colony, Chellapillaikuttai, , 8 16/11/2020 BHUVANESHWARI SARAVANAN (H) 3 736, NAYAKKAR KATTUVALAVU, KOTTAGOUNDAMPATTY, , 9 16/11/2020 CHANDRAKALA V VENKATACHALAM (H) 1/97, JAGADESH NAGAR, PERIYA MOTTUR, , 10 16/11/2020 Palanisamy Madhu (F) 3/242A, Arunthathiyar Street, Saminaickenpatti, , 11 16/11/2020 SANTHOSHKUMAR CHINNADURAI (F) 164A, NETHAJI NAGAR, CHINNADURAI JAGIR AMMAPALAYAM, , 12 16/11/2020 nathiya saravanan (H) 4, krishnanputhur colony, karukkalvadi, , 13 16/11/2020