The Case of Tamil Nadu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Few Translation of Works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets Contents

Few translation of works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets I belong to Kerala but I did study Tamil Language with great interest.Here is translation of random religious works That I have done Contents Few translation of works of Tamil Sidhas, Saints and Poets ................. 1 1.Thiruvalluvar’s Thirukkual ...................................................................... 7 2.Vaan chirappu .................................................................................... 9 3.Neethar Perumai .............................................................................. 11 4.Aran Valiyuruthal ............................................................................. 13 5.Yil Vazhkai ........................................................................................ 15 6. Vaazhkkai thunai nalam .................................................................. 18 7.Makkat peru ..................................................................................... 20 8.Anbudamai ....................................................................................... 21 9.Virunthombal ................................................................................... 23 10.Iniyavai kooral ............................................................................... 25 11.Chei nandri arithal ......................................................................... 28 12.Naduvu nilamai- ............................................................................. 29 13.Adakkamudamai ........................................................................... -

Online Piracy of Indian Movies: Is the Film Industry Firing at the Wrong Target?

ONLINE PIRACY OF INDIAN MOVIES: IS THE FILM INDUSTRY FIRING AT THE WRONG TARGET? Arul George Sea ria* INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 648 I. ONLINE PIRACY OF INDIAN MOVIES ................................................... 649 II. EFFECTIVENESS OF THE LEGAL MEASURES AGAINST ONLINE PIRACY ................................................................................................ 657 III. SUSTAINABLE SOLUTIONS FOR ONLINE PIRACY ................................ 660 CONCLUSION .............................................................................................. 663 ABSTRACT India has recently introduced some digital rights management (DRM) provisions to the Indian copyright law with the objective of providing "adequate" protection for copyrighted material in the online digital environment. Film industry was one of the biggest lobbying groups behind the new DRM provisions in India, and the industry has been consistently trying to portray online piracy as a major threat. The Indian film industry also extensively uses John Doe orders from the high courts in India to prevent the access of Internet users to websites suspected to be hosting pirated material. This paper explores two questions in the context of the new DRM provisions in India: ( 1) Is online piracy a threat to the Indian film industry? and (2) Are the present measures taken by the film industry the optimal measures for addressing the issue of online piracy? Based on data from an extensive empirical -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Digitized Theses Digitized Special Collections 2011 CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA Ganga Rudraiah Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses Recommended Citation Rudraiah, Ganga, "CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA" (2011). Digitized Theses. 3315. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/digitizedtheses/3315 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Digitized Special Collections at Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL: STARS, FANS AND THE STANDARDIZATION OF GENRE IN TAMIL CINEMA r , ' (Spine title: CINEMA OF THE SOCIAL) (Thesis Format: Monograph) by : Ganga Rudraiah Graduate Program in Film Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Ganga Rudraiah 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION r Supervisor Examiners Dr. Christopher E. Glttings Dr. James Prakash Younger Supervisory Committee Dr. Constanza Burucúa Dr. Chris Holmlund The thesis by Ganga Rudraiah entitled: Cinema of the Social: Stars, Fans and the Standardization of Genre in Tamil Cinema is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Date Chair of the Thesis Examination Board Abstract The star machinery of Tamil cinema presents itself as a nearly unfathomable system that produces stars and politicians out of actors and fans out of audiences in an organized fashion. -

Order to Create New Names in a Field. Naming Units Involves Substance Such As Human Knowledge, Human Cognitive Abilities, and Experiences

order to create new names in a field. Naming units involves substance such as human knowledge, human cognitive abilities, and experiences. Onomasiology is inter-related between human minds/cognitive and word formation. Conclusion When morphology enters in word formation automatically semantics changes will occur consequently. There is a clear vision in this word formation which follows the flow as first morphological process and next is semantic change. In between this there is a strong relation between two words while merging together to deliver one meaning. Humans mind is just like a scanner because it will scan object with similar qualities to name another new object they see every day. Onomasiological relation defines relation between two words merged together to deliver one meaning. In this paper, we have offered an overview of word-formation literatures in the light of its sub- domains, namely, Morphology, Lexical, Lexical-semantics, Collocation and Onmasiology. Along the way, we offered a comparative look between popular lexical fraction in Tamil and English, to show that both have almost similar components. Nevertheless, the studies in Tamil on lexical and its semantics confined within grammar framework, yet accrossed the limit to discover its true ability extensively. Only minimal number of studies are available. On the other hand, studies in English in line with the field under observation has been extensively studied. Our expectation is that the lucaritive field of study should be honoured with its deserved stake, proper investigations in Tamil. Bibliography CaritaParadis. (2013). Lexical Semantics. In C. C. A (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Applied Lingustics. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford. -

Enchantment of the Mind Preface

PREFACE 1 March 2004 marked the tenth anniversary of the death of Manmohan Desai. A fall from the terrace of his Khetwadi home brought the 57-year old filmmaker’s life to an end in the spring of 1994. The suspected suicide came as a shock both to those nearest to him and to the film world as a whole, as testified in countless articles and tributes in the Indian and international press in the month following his death. The articles that appeared spanned the gamut of reactions: praise for Desai as a man and as a filmmaker, heartfelt remembrances from those who had worked with him, indignation and disbelief over the circumstances of his death, and speculation over possible motives for suicide— depression over severe backaches being most frequently offered as an explanation. At that time, I could not help feeling a personal sadness over his death. I had, after all, spent the better part of four years studying Manmohan Desai’s work before completing an initial version of this book in 1987. It was, therefore, consoling to have immediate and direct evidence of Manmohan Desai’s work living on beyond his death, as happened one day in 1994 when I walked into an Indian carry-out restaurant in Paris and saw a colorful dance scene from Dharam-Veer playing on the conspicuously placed VCR. Those waiting in line stood transfixed before the screen, their faces radiating joy. Curious to know if Desai’s work had crossed the generations, I asked a young man in his twenties if he knew who had directed the film. -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Sounds of Madras USB Booklet

A R RAHMAN 16 Parandhu Sella Vaa 1 Saarattu Vandiyila O Kadhal Kanmani Kaatru Veliyidai 17 Manamaganin Sathiyam 2 Mental Manadhil Kochadaiiyaan O Kadhal Kanmani 18 Nallai Allai 3 Mersalaayitten Kaatru Veliyidai I 19 Innum Konjam Naeram 4 Sandi Kuthirai Maryan Kaaviyathalaivan 20 Moongil Thottam 5 Sonapareeya Kadal Maryan 21 Omana Penne 6 Elay Keechan Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Kadal 22 Marudaani 7 Azhagiye Sakkarakatti Kaatru Veliyidai 23 Sonnalum 8 Ladio Kaadhal Virus I 24 Ae Maanpuru Mangaiyae 9 Kadal Raasa Naan Guru (Tamil) Maryan 25 Adiye 10 Kedakkari Kadal Raavanan 26 Naane Varugiraen 11 Anbil Avan O Kadhal Kanmani Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 27 Ye Ye Enna Aachu 12 Chinnamma Chilakamma Kaadhal Virus Sakkarakatti 28 Kannukkul Kannai 13 Nanare Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Guru (Tamil) 29 Veera 14 Aye Sinamika Raavanan O Kadhal Kanmani 30 Hosanna 15 Yaarumilla Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa Kaaviyathalaivan 31 Aaruyirae 45 Maanja Guru (Tamil) Maan Karate 32 Theera Ulaa 46 Hey O Kadhal Kanmani Vanakkam Chennai 33 Idhayam 47 Sirikkadhey Kochadaiiyaan Remo 34 Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 48 Nee Paartha Vizhigal - The Touch of Love Vinnaithaandi Varuvaayaa 3 35 Usure pogudhey 49 Ailasa Ailasa Raavanan Vanakkam Chennai 36 Paarkaadhey Oru Madhiri 50 Boomi Enna Suthudhe Ambikapathy Ethir Neechal 37 Nenjae Yezhu 51 Oh Penne Maryan Vanakkam Chennai 52 Enakenna Yaarum Illaye ANIRUDH R Aakko 38 Oh Oh - The First Love of Tamizh 53 Tak Bak - The Tak Bak of Tamizh Thangamagan Thangamagan 39 Remo Nee Kadhalan 54 Osaka Osaka Remo Vanakkam Chennai 40 Don’u Don’u Don’u -

Analysis on Director Ram's Films

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347-4564; ISSN (E): 2321-8878 Vol. 6, Issue 12, Dec 2018, 155-166 © Impact Journals ANALYSIS ON DIRECTOR RAM’S FILMS Arivuselvan. S & Aasita Bali Research Scholar, Department of Media and Communication Studies, Christ (Deemed to be University), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India Received: 15 Nov 2018 Accepted: 12 Dec 2018 Published: 18 Dec 2018 ABSTRACT This case study aims to explore the expertise of a budding, yet prolific director–Director Ram. The paper goes through the work of Director Ram in the Tamil film Industry (Kattradhu Tamizh, ThangaMeengal, Taramani) and aims to focus on the content of the films directed by him. The researcher, in his paper analyzes the types and kind of movies that the director has been a part of and the different types of techniques that he adopted and executed in his films. The researcher also analyses in detail, the type of character and highlighted the multifaceted role of women as portrayed in his films. KEYWORDS: Direction, Cinematography, Protagonist, Women, Characters, Film Industry, Globalization INTRODUCTION Indian cinema has been a standout amongst the most continually developing film ventures everywhere throughout the world. The wide variety and the number of dialects that are used in the nation, make the Indian film industry standout as the leading film producing unit. Indian film is a plethora of numerous dialects, classifications, and social orders. In any case, in a multilingual nation like our own, the significant focal point of the movies is on Bollywood. It is not valid if critiques and reviewers point out that the industry is notwithstanding the pressure or competition from Hollywood. -

Rudram Chamakam Pdf in Kannada

Rudram chamakam pdf in kannada Continue prayato brahmak ar suklav as dev abhimukhah. In addition, the PDF files on this site needs Adobe Reader 9.0 or higher. A collection of spiritual and devoted literature in various Indian languages in Sanskrit, Samscrehame, Hindi, Telugu, Cannada, Tamil, Malayalam, Gujarati, Bengal, Oriya, English scripts with pdf Sri Rudram namak-chamakam: Lyrics (Sanskrit) Sri Rudrum (ी म्), is a Hindu stotra (hymn) dedicated to Rudra (expression of Lord Shiva) It is also called Rudradhyaya, Sri Rudraprasna, zatarudraya. A collection of spiritual and devoted literature in various Indian languages in Sanskrit, Samskrit, Hindi, Telugu, Kannada, Tamila, Malayalam, Gujarati, Bengal, Aurier, English scripts with pdf Kashyap from SAKSI (Sri Aurobindo Kapalitry Sas Institute of Vedic Culture), Bangalore, India. Rudram Chamakam Kannada - Free download as a PDF file (.pdf), text file (.txt) or view presentation slides online. Sri Rudram talks about Siva's fame. Sri Rudram is a Vedic hymn that describes several aspects of Mr. Siwa, such as Sri Rudram Chamakam as Kannada Vidik Vinyanam. Scribd is the world's largest social reading and publishing site. Sri Rudram takes place in the 4th Place in the 4th Hand of Krishna Yadjour Samhita. Sri-Rudram-Namakam-In-Kannada.pdf - Free download as PDF file (.pdf), text file (.txt) or read online for free. The collection of spiritual and dedicated literature in various Indian languages in Sanskrit, Samscretam, Hindi, Telugu, Kannada, Tamil, Malayalam, Gujarati, Bengal, Aurier, English scripts with pdf Scribd is the world's largest social site for reading and publishing. Sri Rudram with meaning. Page 2 of 13 bl? Search Search with m / Aaej?I /sh?m / Aai?I bala×a maa oya×ka me saha×ca ma'i'i me Let my action bodies be strong and courageous. -

Mess Bill for December 2013

DECEMBER 2013 MESS BILL LIST ( REGULAR & VACATION MESS) A & B MESS srno Roll No Name Mess total 1 101113001 A J SUDHI A & B 1390 2 101113002 ADAPALA ARAVINDH BABU A & B 1390 3 101113004 AMIT KUMAR A & B 1390 4 101113005 AMITHVISHAL. P A & B 1515 5 101113007 ANGAMBA NAMEIRAKPAM A & B 1562 6 101113008 ANIRUDH DEORAH A & B 1620 7 101113010 ANWIN P S A & B 1714 8 101113011 ARUN. M.V A & B 1340 9 101113012 ASHISH RANJAN A & B 1340 10 101113014 CHANDU SAI TARUN A & B 1759 11 101113016 GUDALA DILEEP A & B 1390 12 101113017 HUKUMU RIO DEBBARMA A & B 1599 13 101113019 JULIAN DIVAKAR A A & B 1190 14 101113020 KARNIK N HEGDE A & B 1390 15 101113021 KOKKIRALA HARSHA VARDHAN RAO A & B 1390 16 101113022 KUMAVATH CHANDRA SHEKHAR NAIK A & B 1412 17 101113024 M GOKUL ANAND A & B 1390 18 101113025 MADAM MALLIKARJUN A & B 1390 19 101113026 MAHONRING SHAIZA A & B 1801 20 101113027 MOHAMMED SIRAJUDDIN A & B 1390 21 101113029 NIKHIL CHOPRA GALIMOTU A & B 1190 22 101113030 NILESH ROY A & B 1593 23 101113034 RAFAEL WILLIAMS MANNERS A & B 1390 24 101113035 RAHUL SOMARAJAN NAIR A & B 1340 25 101113036 RAVIPUDI SRIKANTH A & B 1340 26 101113037 S N MITHUN BALAJI A & B 1340 27 101113038 S P GANESHAN A & B 1390 28 101113039 S SANTHOSH A & B 1728 29 101113040 S SIDDHARTH A & B 1390 30 101113042 SHAHUL SHANAVAS S A & B 1390 31 101113043 SIDHARTH.K A & B 1390 32 101113045 SRIRAM R A & B 1540 33 101113048 YOKESHWAR ELANGOVAN A & B 1390 34 102113001 A C M ABINESH KUMAR A & B 1390 35 102113002 AKSHAY MURALI A & B 1500 36 102113003 AMAN KUMAR BAKOLIA A & B 1390 37 102113005 ANIKET GUPTA A & B 1340 38 102113006 ANNAM JHANSI SHRAVAN A & B 1557 39 102113008 AREPALLI PHANENDRA A & B 1390 40 102113009 ARVIND PARI A & B 1340 41 102113010 ARVIND SRIVATSAVA. -

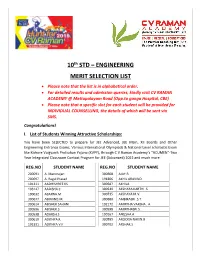

10Th STD – ENGINEERING MERIT SELECTION LIST Please Note That the List Is in Alphabetical Order

10th STD – ENGINEERING MERIT SELECTION LIST Please note that the list is in alphabetical order. For detailed results and admission queries, kindly visit CV RAMAN ACADEMY @ Mettupalayam Road (Opp.to ganga Hospital, CBE) Please note that a specific slot for each student will be provided for INDIVIDUAL COUNSELLING, the details of which will be sent via SMS. Congratulations! I. List of Students Winning Attractive Scholarships: You have been SELECTED to prepare for JEE Advanced, JEE Main, XII Boards and Other Engineering Entrance Exams, Various International Olympiads & National Level scholastic Exam like Kishore Vaigyanik Protsahan Yojana (KVPY), through C V Raman Academy’s “ACUMEN”-Two Year Integrated Classroom Contact Program for JEE (Advanced) 2022 and much more. REG.NO STUDENT NAME REG.NO STUDENT NAME 200091 A. Manorajan 300668 AJAY.R 200097 A. Ragul Prasad 191806 AKHIL ARAVIND 191211 AADHISHREE KS 300587 AKHILA 193127 AADISHA.C 300549 AKSHARA KARTHI .S 190632 ABARNA.M 300735 AKSHAYA.M.V. 300677 ABINAND.M. 300680 AMBIKASRI .S.T. 300614 ABISHEK SAHANI 192172 AMIRTHA VARSHA . A 300596 ABISHEK.S 300598 AMIRTHASRI.S. 300538 ADARSH.S 190167 ANUSHA.A 300619 ADITHYA.R 300595 AROCKIA NAVIN.B 192331 ADITHYA.V.K 300702 ARSHAK.S REG.NO STUDENT NAME REG.NO STUDENT NAME 190023 ASHVANTH .N 300566 DHIVYA DHARSHINI .V 300646 ASHWIN.R. 300720 DINESH KUMAR.A 300718 ASWIN.T.M. 300699 DINESH RAM.B 300713 ASWINRAM.A 300717 DINESH.P.R. 300641 ATHISH .A.S. 300686 DIVYA.U. 300642 ATHISH.K.S. 300667 Dolly Jain.M 300662 ATHUL KRISHNA .P. 300577 DOMNIC RICHARD .D 300700 AYUSH KUMAR 300609 DUSHYANTH 200090 B.