The Architecture of Fauna in Turkey: Birdhouses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

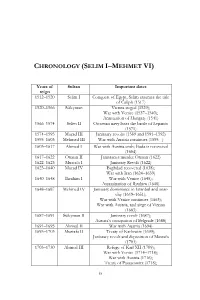

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2294

ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: LNG2014-1176 Athens Institute for Education and Research ATINER ATINER's Conference Paper Series ARC2017-2294 Changing Urban Pattern of Eminönü: Reproduction of Urban Space via Current Images and Function Tuba Sari Research Assistant Istanbul Technical University Turkey 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2017-2294 An Introduction to ATINER's Conference Paper Series ATINER started to publish this conference papers series in 2012. It includes only the papers submitted for publication after they were presented at one of the conferences organized by our Institute every year. This paper has been peer reviewed by at least two academic members of ATINER. Dr. Gregory T. Papanikos President Athens Institute for Education and Research This paper should be cited as follows: Sari, T. (2017). "Changing Urban Pattern of Eminönü: Reproduction of Urban Space via Current Images and Function", Athens: ATINER'S Conference Paper Series, No: ARC2017-2294. Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece Tel: + 30 210 3634210 Fax: + 30 210 3634209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr URL Conference Papers Series: www.atiner.gr/papers.htm Printed in Athens, Greece by the Athens Institute for Education and Research. All rights reserved. Reproduction is allowed for non-commercial purposes if the source is fully acknowledged. ISSN: 2241-2891 06/11/2017 ATINER CONFERENCE PAPER SERIES No: ARC2017-2294 Changing Urban Pattern of Eminönü: Reproduction of Urban Space via Current Images and Function Tuba Sari Abstract Considering the mixture of civilizations as one of the central locations of Istanbul, the Eminonü district has many different urban patterns related to its historical background. -

Women and Power: Female Patrons of Architecture in 16Th and 17Th Century Istanbul1

Women and Power: Female Patrons of Architecture in 16th and 17th Century Istanbul1 Firuzan Melike Sümertas ̧ Anadolu University, Eskisehir, ̧ TÜRKlYE ̇ The aim of this paper is to discuss and illustrate the visibility of Ottoman imperial women in relation to their spatial presence and contribution to the architecture and cityscape of sixteenth and seventeenth century Istanbul. The central premise of the study is that the Ottoman imperial women assumed and exercised power and influence by various means but became publicly visible and acknowledged more through architectural patronage. The focus is on Istanbul and a group of buildings and complexes built under the sponsorship of court women who resided in the Harem section of Topkapı Palace. The case studies built in Istanbul in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are examined in terms of their location in the city, the layout of the complexes, the placement and plan of the individual buildings, their orientation, mass characteristics and structural properties. It is discussed whether female patronage had any recognizable consequences on the Ottoman Classical Architecture, and whether female patrons had any impact on the building process, selection of the site and architecture. These complexes, in addition, are discussed as physical manifestation and representation of imperial female power. Accordingly it is argued that, they functioned not only as urban regeneration projects but also as a means to enhance and make imperial female identity visible in a monumental scale to large masses in different parts of the capital. Introduction Historical study, since the last quarter of the 20th The study first summarizes outlines the role of women century has concentrated on recognizing, defining, in the Ottoman society. -

The Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque.Pdf

Paper prepared for the Third Euroacademia Forum of Critical Studies Asking Big Questions Again Florence, 6–7 February 2015 This paper is a draft Please do not cite 1 The Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Camii: “An Auspicious Building On An Auspicious Site” Bahar Yolac Pollock, Phd candidate Koc University, Istanbul Abstract The Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque was inaugurated in 1871 by the mother of Sultan Abdülaziz (r. 1861-1876). It was the last example of the long Ottoman tradition of royal mosque complexes, but neither twentieth-century urban developers nor historians of Ottoman art have had much regard for this monument, likely because the decoration and tectonic structure of the mosque reflect a vast span of Ottoman, Moorish, Gothic and Renaissance styles. The amalgamation of these styles was often condemned in the old paradigm of Ottoman architectural history as a garish hodgepodge lacking the grandeur of classical Ottoman architecture. This paper will examine why and how such preferences emerged and establish what Michael Baxandall has called the “period eye.” Furthermore, I will investigate a point that Ottoman art historians who have explained the choice of style have omitted: nowhere do they mention the importance of the site for the valide sultan and the imperial family. My paper will thus contextualize the complex within the larger nineteenth-century urban fabric and the socio-political circumstances to elucidate better its function and significance. Overall I argue that the rich hybridity of the building together with the choice of its location was intended to testify to the powerful dynastic presence during particularly tumultuous years of the empire, while also projecting the aspirations of a strong female figure of the Ottoman dynasty. -

Turkish Plastic Arts

Turkish Plastic Arts by Ayla ERSOY REPUBLIC OF TURKEY MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM PUBLICATIONS © Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism General Directorate of Libraries and Publications 3162 Handbook Series 3 ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 www.kulturturizm.gov.tr e-mail: [email protected] Ersoy, Ayla Turkish plastic arts / Ayla Ersoy.- Second Ed. Ankara: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2009. 200 p.: col. ill.; 20 cm.- (Ministry of Culture and Tourism Publications; 3162.Handbook Series of General Directorate of Libraries and Publications: 3) ISBN: 978-975-17-3372-6 I. title. II. Series. 730,09561 Cover Picture Hoca Ali Rıza, İstambol voyage with boat Printed by Fersa Ofset Baskı Tesisleri Tel: 0 312 386 17 00 Fax: 0 312 386 17 04 www.fersaofset.com First Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2008. Second Edition Print run: 3000. Printed in Ankara in 2009. *Ayla Ersoy is professor at Dogus University, Faculty of Fine Arts and Design. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 Sources of Turkish Plastic Arts 5 Westernization Efforts 10 Sultans’ Interest in Arts in the Westernization Period 14 I ART OF PAINTING 18 The Primitives 18 Painters with Military Background 20 Ottoman Art Milieu in the Beginning of the 20th Century. 31 1914 Generation 37 Galatasaray Exhibitions 42 Şişli Atelier 43 The First Decade of the Republic 44 Independent Painters and Sculptors Association 48 The Group “D” 59 The Newcomers Group 74 The Tens Group 79 Towards Abstract Art 88 Calligraphy-Originated Painters 90 Artists of Geometrical Non-Figurative -

The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa's Diary

Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.) The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak Memoria. Fontes minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici pertinentes Edited by Richard Wittmann Memoria. Fontes Minores ad Historiam Imperii Ottomanici Pertinentes Volume 2 Paulina D. Dominik (Ed.): The Istanbul Memories in Salomea Pilsztynowa’s Diary »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (1760) With an introduction by Stanisław Roszak © Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, Bonn 2017 Redaktion: Orient-Institut Istanbul Reihenherausgeber: Richard Wittmann Typeset & Layout: Ioni Laibarös, Berlin Memoria (Print): ISSN 2364-5989 Memoria (Internet): ISSN 2364-5997 Photos on the title page and in the volume are from Regina Salomea Pilsztynowa’s memoir »Echo of the Journey and Adventures of My Life« (Echo na świat podane procederu podróży i życia mego awantur), compiled in 1760, © Czartoryski Library, Krakow. Editor’s Preface From the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to Istanbul: A female doctor in the eighteenth-century Ottoman capital Diplomatic relations between the Ottoman Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Com- monwealth go back to the first quarter of the fifteenth century. While the mutual con- tacts were characterized by exchange and cooperation interrupted by periods of war, particularly in the seventeenth century, the Treaty of Karlowitz (1699) marked a new stage in the history of Ottoman-Polish relations. In the light of the common Russian danger Poland made efforts to gain Ottoman political support to secure its integrity. The leading Polish Orientalist Jan Reychman (1910-1975) in his seminal work The Pol- ish Life in Istanbul in the Eighteenth Century (»Życie polskie w Stambule w XVIII wieku«, 1959) argues that the eighteenth century brought to life a Polish community in the Ottoman capital. -

Arab Scholars and Ottoman Sunnitization in the Sixteenth Century 31 Helen Pfeifer

Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Islamic History and Civilization Studies and Texts Editorial Board Hinrich Biesterfeldt Sebastian Günther Honorary Editor Wadad Kadi volume 177 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ihc Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Edited by Tijana Krstić Derin Terzioğlu LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “The Great Abu Sa’ud [Şeyhü’l-islām Ebū’s-suʿūd Efendi] Teaching Law,” Folio from a dīvān of Maḥmūd ‘Abd-al Bāqī (1526/7–1600), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The image is available in Open Access at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447807 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Krstić, Tijana, editor. | Terzioğlu, Derin, 1969- editor. Title: Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 / edited by Tijana Krstić, Derin Terzioğlu. Description: Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Islamic history and civilization. studies and texts, 0929-2403 ; 177 | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

THE ISLAMIC COINS Athens at BY

THE ATHENIANAGORA RESULTS OF EXCAVATIONS CONDUCTED BY THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS VOLUME IX THE ISLAMIC COINS Athens at BY GEORGE C. MILES Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. License: Classical of o go only. .,0,00 cc, 000, .4. *004i~~~a.L use School personal American © For THE AMERICAN SCHOOL OF CLASSICAL STUDIES AT ATHENS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1962 American School of Classical Studies at Athens is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to The Athenian Agora ® www.jstor.org PUBLISHED WITH THE AID OF A GRANT FROM MR. JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR. Athens at Studies CC-BY-NC-ND. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED License: Classical of only. use School personal American © For PRINTED IN GERMANY at J.J. AUGUSTIN GLO CKSTADT PREFACE T he present catalogue is in a sense the continuation of the catalogue of coins found in the Athenian Agora published by MissMargaret Thompson in 1954, TheAthenian Agora: Results of the Excavations conductedby the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, Volume II, Athens Coins from the Roman throughthe Venetian Period. Miss Thompson's volume dealt with the at Roman, Byzantine, Frankish, Mediaeval European and Venetian coins. It was in the spring of 1954 that on Professor Homer A. Thompson's invitation I stopped briefly at the Agora on my way home from a year in Egypt and made a quick survey of the Islamic coins found in the ex- cavations. During the two weeks spent in Athens on that occasion I looked rapidly through the coins and that their somewhat and their relative Studies reported despite unalluring appearance CC-BY-NC-ND. -

Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration

Sultan Ahmed III’s calligraphy of the Basmala: “In the Name of God, the All-Merciful, the All-Compassionate” The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne Note on Transliteration In this work, words in Ottoman Turkish, including the Turkish names of people and their written works, as well as place-names within the boundaries of present-day Turkey, have been transcribed according to official Turkish orthography. Accordingly, c is read as j, ç is ch, and ş is sh. The ğ is silent, but it lengthens the preceding vowel. I is pronounced like the “o” in “atom,” and ö is the same as the German letter in Köln or the French “eu” as in “peu.” Finally, ü is the same as the German letter in Düsseldorf or the French “u” in “lune.” The anglicized forms, however, are used for some well-known Turkish words, such as Turcoman, Seljuk, vizier, sheikh, and pasha as well as place-names, such as Anatolia, Gallipoli, and Rumelia. The Ottoman Sultans Mighty Guests of the Throne SALİH GÜLEN Translated by EMRAH ŞAHİN Copyright © 2010 by Blue Dome Press Originally published in Turkish as Tahtın Kudretli Misafirleri: Osmanlı Padişahları 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Published by Blue Dome Press 535 Fifth Avenue, 6th Fl New York, NY, 10017 www.bluedomepress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available ISBN 978-1-935295-04-4 Front cover: An 1867 painting of the Ottoman sultans from Osman Gazi to Sultan Abdülaziz by Stanislaw Chlebowski Front flap: Rosewater flask, encrusted with precious stones Title page: Ottoman Coat of Arms Back flap: Sultan Mehmed IV’s edict on the land grants that were deeded to the mosque erected by the Mother Sultan in Bahçekapı, Istanbul (Bottom: 16th century Ottoman parade helmet, encrusted with gems). -

Impact of Land Use Changes on the Authentic Characteristics of Historical Buildings in Bursa Historical City Centre

IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGES ON THE AUTHENTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN BURSA HISTORICAL CITY CENTRE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY AYŞEGÜL KELEŞ ERİÇOK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CITY AND REGIONAL PLANNING OCTOBER 2012 Approval of the thesis: IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGES ON THE AUTHENTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN BURSA HISTORICAL CITY CENTRE submitted by AYŞEGÜL KELEŞ ERİÇOK in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of City and Regional Planning, Middle East Technical University by, Prof. Dr. Canan ÖZGEN _____________________ Dean, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences Prof. Dr. Melih ERSOY _____________________ Head of Department, City and Regional Planning Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA _____________________ Supervisor, City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Anlı ATAÖV _____________________ City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Numan TUNA _____________________ City and Regional Planning Dept., METU Prof. Dr. Gül ASATEKİN _____________________ Architecture Dept., Bahçeşehir University Prof. Dr. Ruşen KELEŞ _____________________ Faculty of Political Sciences, Ankara University Prof. Dr. Zuhal ÖZCAN _____________________ Architecture Dept., Çankaya University Date: October 5, 2012 I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Ayşegül Keleş Eriçok Signature : iii ABSTRACT IMPACT OF LAND USE CHANGES ON THE AUTHENTIC CHARACTERISTICS OF HISTORICAL BUILDINGS IN BURSA HISTORICAL CITY CENTRE Keleş Eriçok, Ayşegül Ph.D., Department of City and Regional Planning Supervisor: Prof. -

Üsküdar As the Site for the Mosque Complexes of Royal Women in the Sixteenth Century

ÜSKÜDAR AS THE SITE FOR THE MOSQUE COMPLEXES OF ROYAL WOMEN IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY by SINEM ARCAK Submitted to the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University Fall 2004 ÜSKÜDAR AS THE SITE FOR THE MOSQUE COMPLEXES OF ROYAL WOMEN IN THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY APPROVED BY: Prof. Dr. Metin Kunt …………………………. (Dissertation Supervisor) Prof. Dr. Stefanos Yerasimos …………………………. Associate Prof. Dr. Tülay Artan …………………………. DATE OF APPROVAL: 2 November 2004 {PAGE } © Sinem Arcak 2004 All Rights Reserved Sevgi, Ahmet, Doğan, Hüsnü, bu size.. {PAGE } ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am truly indebted to my advisor, Professor Metin Kunt, for his generous advice and encouragement. I would also like to thank Professor Stefanos Yerasimos for his invaluable guidance and for directing my attention to sources that I have used extensively. Many thanks as well to Professor Tülay Artan for all her help and assistance. For her careful editing and constructive advice, I thank Professor Catherine Asher. Without the love and support of my friends I could never have completed this thesis. I would like to thank my fellow students Sevgi Adak, Ahmet Izzet Bozbey, Dogan Gürpınar, Hüsnü Ada, Aysel Yıldız, Zeynep Yelçe, Tuba Demirci, Selçuk Dursun, and Candan Badem. I would also like to thank my friends Selin Kesebir and Ahu Gemici for their endless support. I am grateful to Nina Cichocki, from the University of Minnesota, for kindly allowing me to read chapters from her dissertation and for letting me share a copy of the “Nurbanu Sultan Vakfiyesi.” Finally, I thank those closest to me—my mother Dilek Ayaş, my sister Sena Arcak, and Çağrı Ekiz—who have supported me with their love and patience. -

The Eighteenth Century Defining the Crisis

Chapter 2 The Eighteenth Century Defining the Crisis The traditional accounts of the eighteenth-century Ottoman Empire focus on wars, the end of territorial expansion, and socioeconomic and military weakness—all taken as clear indications of decline. An alternative “eventful history” of the same century, however, requires attention to internal rather than external developments. In her analysis of this period, Karen Barkey exam- ines the structural changes put into motion by the events of 1703, 1730, and 1808.1 She goes on to compare the Edirne incident and the Patrona Halil rebel- lion to the revolutions of 1848 in Europe.2 Indeed, these events can be under- stood as turning points in state-society transformations (or “readjustments” as Barkey calls them) in the eighteenth century. For this study, it is also important to include the 1740 market revolt in Istanbul. This book is based on the premise that the long term, combined impact of these events set the stage for Selim’s new measures and policies as manifestations of a perceived threat of unruly elements of the population and a desire to control them more effectively. The beginning of the eighteenth century was marked by the return of the Ottoman court to Istanbul from Edirne in 1703.3 This shift initiated a process of unprecedented building activity and urban change in Istanbul; government efforts to reassert the physical presence and authority of the Ottoman sultan in the imperial capital were crucial to the formation of the new urban environ- ment.4 Throughout the eighteenth century, the government tightened existing laws and promulgated new ones to regulate urban life in the city, utilizing its police force, composed mostly of janissaries, to ensure conformity.